The ‘intentional fallacy’ was proposed by Wimsatt and Beardsley in 1954 in The Verbal Icon. It suggested that no work of art, especially a literary one, should be read with an assumption that the author’s ‘intention’ with regard to the poem’s meaning or function as discourse should or indeed can be made. Yet scholarship remained besotted, especially in visual art history and, worse, in art criticism or appreciation with the search for external evidence of an artwork’s meaning, as if such material evidence alone provided access to the art as it should be read. Now I don’t believe that a poem or a painting can ‘mean anything’ and is subject only to each reader’s or viewer’s distinct character as a reader or viewer rather than to a view of it that seeks some ‘objectivity’ of reading, but the main argument for the truth of the ‘intentional fallacy’ is a lyric like number 155 of Alfred Tennyson’s In Memoriam. This startling poem seems belied by its stated intention as a statement that lives in its final stanza. Below is the lyric as a whole.

In Memoriam lyric XLV

The baby new to earth and sky,

What time his tender palm is prest

Against the circle of the breast,

Has never thought that "this is I:”

But as he grows he gathers much,

And learns the use of "I” and „me,”

And finds "I am not what I see,

And other than the things I touch.”

So rounds he to a separate mind

From whence clear memory may begin,

As thro’ the frame that binds him in

His isolation grows defined.

This use may lie in blood and breath,

Which else were fruitless of their due,

Had man to learn himself anew

Beyond the second birth of Death.

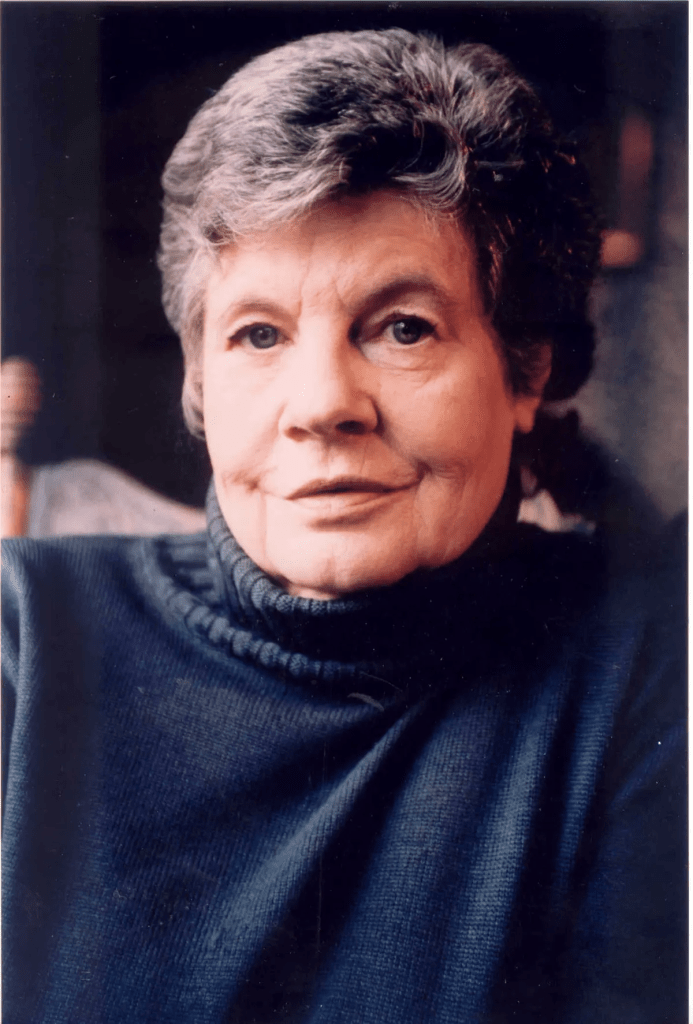

This poem matters to me partly in memoriam of the novelist, poets and critic A.S. Byatt who taught Victorian literature to me and others in my year-group at University College London and was my tutor. For Byatt, and now for me, this poem startles through the sense of horror and hopelessness in some of its lines and dead imagery – which I find resonantly alive again as I read it – not least the lines in the penultimate stanza:

As thro’ the frame that binds him in

His isolation grows defined.

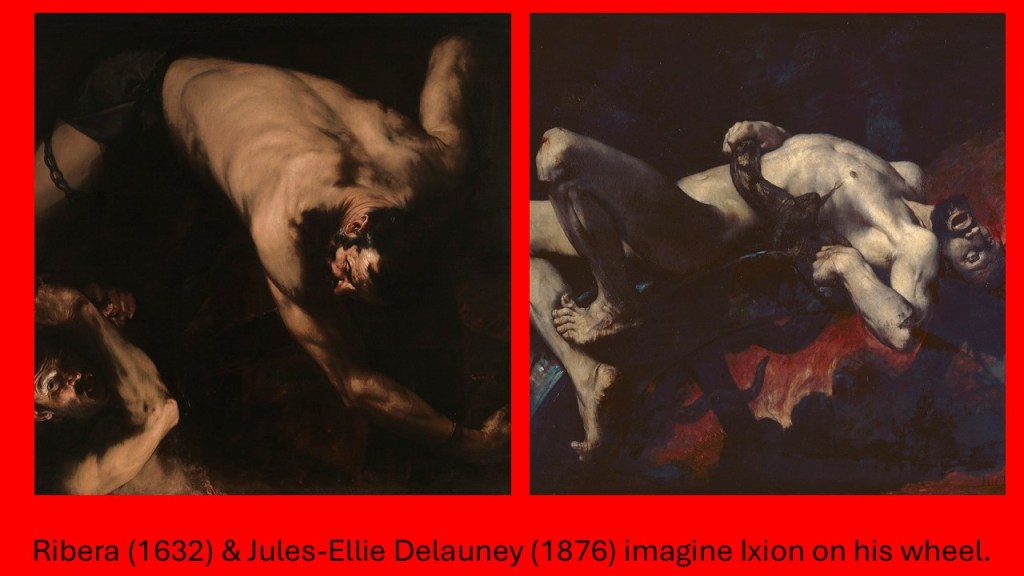

The ‘frame’ might be an abstraction but it feels to me as I read to be as internally if not physically or externally visceral as the wheel binding Ixion:

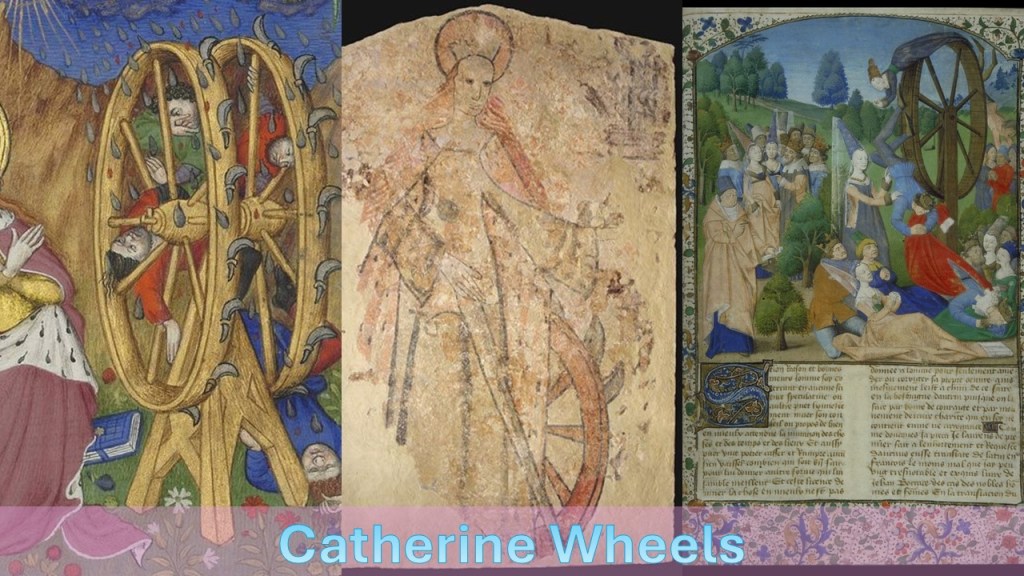

Or maybe you prefer to think of St Catherine on her medieval breaking wheel.

Frames are equally it is a form of bondage not unlike that of Lear in Act IV Scene 7 imagining himself as being as internally scarred as if he were viscerally ‘bound / Upon a wheel of fire, that mine own tears / Do scald like molten lead’. Of course the ‘frame’ is a metaphor for skeleton and fleshly skin-bounded body. But that argument for it being a dead metaphor ignores the ways in which such metaphors get revived in certain context, such as the use of dead metaphors of punishment by bondage or incarceration. The process of living, this part lyric suggests is a process of on’s ‘isolation’ growing defined within the bounds of that body like its frame that ‘BINDS him in’.

A growing thing is sometimes painfully confined in a frame without flexibility, whether that be instrument of torture, corset or a skin that does not grow to fit its growing contents. In Tennyson, the image may not be as visceral as Lear’s image, and is less about just or unjust judicial torture as with Ixion and Catherine, but it can be terrifying or numbing (as images in Emily Dickinson deliberately numb) depending on any reader’s response to images of being ‘locked in’. Tennyson goes to some lengths to make ‘in’ the end word in his stanza so that it bears the weight of stress of last syllable of the line and rhyme. To get one’s ‘isolation defined’ (forever) is no innocent thing – personal identity begins to feel a label that shames and punishes.

The last stanza however seems to talk on as if these effects were as nothing and the language of the poem more tending to the discourse of informal philosophical argument. It says: ‘I told you about all the above processes undergone in adult development from the childhood, to illustrate that our individual identities, though formed by behavioural, cognitive and affective learning, are gained in embodied so that they live on forever in the spiritual after-life. This was a thought I remember Byatt shuddering at, as do I now – a thought more horrible than the worst dreamed up by the spiritual fathers to describe Hell.

For Byatt, and again now forever for me, this poem fed from Lamarckian evolutionary thinking to prefigure a theory more associated later with Freud, and later Lacan, about the formation of human identity phylogenetically in every baby from a begiining in which the baby felt itself continuous with the internal and external world, not ‘other’ than the things it touched. Hence the mother’s breast ‘against which’ it ‘tender palm’ is ‘prest’ is, to the baby as much part of itself as any other thing in the reach of its senses, particularly that of that grasping hand. The echo here seems to me to be an echo of Melanie Klein not Freud or Lacan. According to her the conceptual and sensual break up of breast from child leads to the birth of the paranoid-schizoid affective position in the baby and the formation of paranoid schizoid phantasies of the good breast (that stays to meet your need) and bad breast (that goes away in pursuit of its own agenda and is felt by the baby as so punishing that t must be punished in return.

Yet again there is little of that in Tennyson’s version – at least apparently:

The baby new to earth and sky,

What time his tender palm is prest

Against the circle of the breast,

Has never thought that „”his is I:”

But as he grows he gathers much,

And learns the use of “I” and “me,”

And finds “I am not what I see,

And other than the things I touch.”

So rounds he to a separate mind

From whence clear memory may begin,

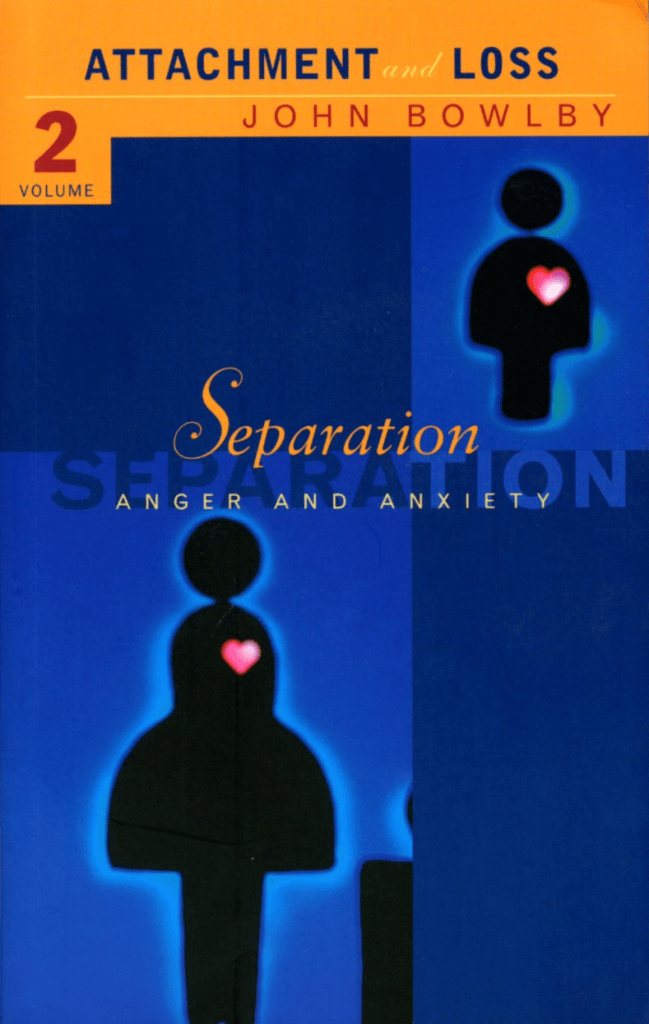

Tennyson’s baby ’rounds’ into ‘separation’ with the separation anxiety predicted by the object-relations psychodynamic theorists who followed Klein (Fairbairn and even Bowlby) but the signs of this primal anxiety are there to intuit as Byatt argued. She used this lyric to point to the frequency of object-related circle and dynamic circling motion imagery in the poem. The breast is a ‘circle’ and its link of tender skin-to-skin contact is that of palm of baby’s hand and the breast’s warm skin covering. That circle shifts. Development of self is a process of rounding – like circle in formation around its own centre ’rounds he to a separate mind’. However, although that is or seems a constructive process it is also a destructive and fragmenting one – part of the processes of ‘splitting’ analysed by Fairbairn from Klein’s prompts and symptomatised in the ‘separation anxiety’ that betokens the other side of attachment relations in Bowlby and is the subject of Volume II of his Attachment & Loss volumes.

For me the suppression of this fragmentation is vital to Tennyson, though his whole oeuvre shows him aware of it from his early suicide poems onwards (The Two Voices‘ in particular). It is the tragedy of life for Tennyson I think to ‘other than the things I touch’, especially because touch is no simple dead and un-resurrect-able metaphor here – it recalls the ‘tender palm’ pressed om the ‘breast’, nervous entirely that the tenderness of the ‘touch’ will always be betrayed,as Klein insisted. For Klein that was why there was a need to substitute for the inner pain of the paranoid-schizoid position by the ‘depressive position’ – in fact a neutral state (though a sad one) of acceptance that the child’s needs, wants and desires are not primary in the world into which they have been born ‘new to earth and sky’.

To become an “I” (or an ‘eye’ divorced from ‘that it sees’) is to learn and inhabit a state of being to which all is other and motivated by what is other and not by your ‘touch’, which i think is all the index of your projected internal feelings in this case’.

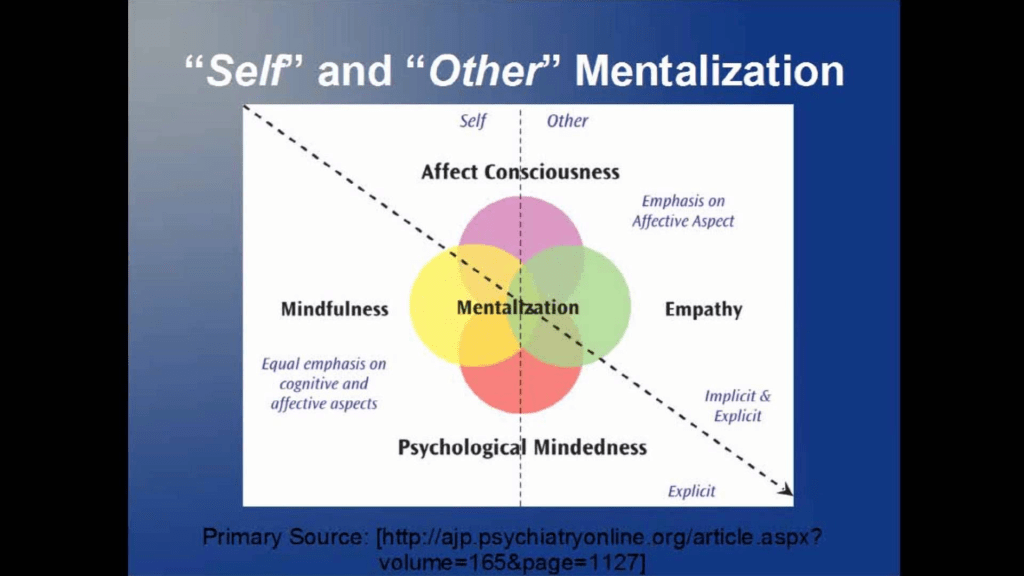

I was prompted to think of all this because a dear friend of mine is receiving ‘therapeutic’ (the scare quotes are because she does not feel made better by the intervention, or NOT YET – she is a most open person) input called by the therapist ‘mentalisation’ or MBT (mentalisation-based therapy).The link will give a taste of the approach. Though supposedly born as an adaptation of interactions between psychodynamic, cognitive-affective and behavioural approaches, it is now firmly bound into the tools of Positive Psychology. The justification of the approach is below:

The premise of this therapy is rooted in the concept of “mentalizing.” Mentalizing is the ability to identify and differentiate one’s own emotional state from that of others (Bateman & Fonagy, 2013).

It is the ability to understand how our mental state influences behavior and emotions. Essentially, mentalization describes the common psychological process people use to understand the mental states, emotions, beliefs, desires, and intentions that are the basis of interpersonal interactions.

Because the ability to mentalize is foundational to psychological health and resilience, the main goals of MBT are to improve mentalization and learn emotional regulation. MBT includes elements from psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, systemic, and social-ecological therapies (Lois et al., 2016).

MBT practitioners try to establish a secure therapeutic attachment with patients and create a safe environment so clients can explore personal feelings and the feelings of others to develop their capacity to mentalize.

Much of MBT is grounded in attachment theory, in which infants activate attachment by communicating emotional distress with their caretakers. Secure attachment facilitates the development of healthy mentalization (Fonagy & Allison, 2014).

However, individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) commonly have preoccupied, fearful, distrustful, hostile, and disorganized attachment, which is addressed in MBT. The attachment style of BPD clients is one that fails to establish and regulate a sense of safety, creating distress, unhealthy vulnerability, and emotional dysregulation (Lois et al., 2016).

The ability to mentalize helps those with BPD understand their mental states, stabilize emotions, develop empathy, and improve interpersonal relationships.

The grounding in Bowlby is stressed here, but not the understanding of the affective as the record of significant separation crises out of which that approach was born – by which I mean what I say of Klein above. Mentalisation (allow me to use Anglicized spelling) is in truth an edited down version of any true psychodynamic approach in the interests of patient safety – it neglects therefore to address the traumatic separations (whether they be events like abuse or magnified effects of normative processes in sensitive neuro-atypical persons) that might lie in the aetiology (or causation) of the feelings suffered by a ‘patient’ or ‘client’. It was created thus to be used by clinicians with medium-level skills, knowledge and values (not fully trained – and analysed – psychoanalysts), without fear of leading the patient into triggered regression into the original trauma.

In my feeling it is still potentially dangerous. It tends to work only with the patient’s social cognitions to shift interpretations based on paranoid-schizoid thinking (this is not a label – it is the thinking of us all at certain points in life) where others are interpreted as ‘bad breasts’ (deliberately antagonistic to us, where we believe thee ought to meet our needs). It constantly asks the analysand to query their way of thinking about people – especially helping professionals or relatives – asking them to consider likely difference in their agenda or experience that may not take one into account but are not malignantly intended or in some other way ‘bad’. As a result the analysand is I think conditioned (despite words to the opposite from a kind and well-intentioned therapist) to see themselves as the source of all fault and blame rather than understanding that responsibility is distributed withing human systems and rarely owned nor acknowledged by anyone.

In effect I fear the analysand is left without defence from the fact that their ‘isolation’ is constantly being ‘defined’, reminded that they are ‘other than the things’ they ‘touch’ and without any control that is not merely self-regulating rather than addressed to ameliorating social systems. They may bew left in the infernal depths of the ‘depressive position’ because of that dynamic. They should not be there and need to resist being put there, perhaps by ensuring they do not swallow the approach as the whole issue, rather than tinkering with the symptoms of trauma. if it does the latter well – let it. But beware the hubris of therapists who think their skills paramount. There is no way that they could be.

Meanwhile use Tennyson to help. He visited the infernal depths of Hades / Hell like Ulysses in The Odyssey and came back to report that survival is possible and to be fostered through friends and allies, and learning love what is vulnerable at your core.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxx (especially to my dear friend)