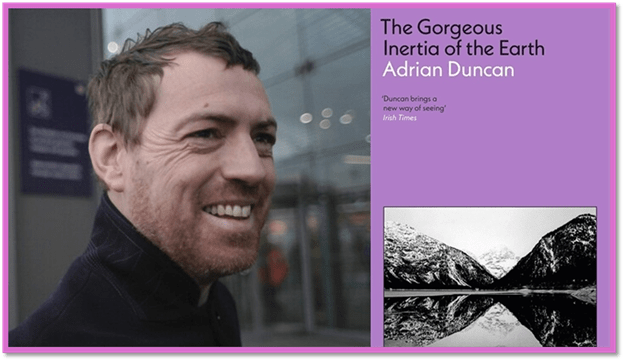

‘…, and yet there is something in the form that does not make sense to me’.[1] The beautiful new novel by Adrian Duncan The Gorgeous Inertia of the Earth (2025) imagines a project in which the ‘history from within’ is sought of ‘selected sculptures’.[2] That history in a novel extends to the people who work on the project, the cultures which formed them, and the various inter-relationships between these elements. In the process we confront the need for an analytic approach to the nature of the variability of strengths and vulnerability in stone types called a ‘taxonomy of stone’, that runs alongside the internal synthetic one with regard to the sculpture as a whole. This complex dialectic amounts to an approach to re-imagining the nature of inertia or stillness in art, life and communion between living things.

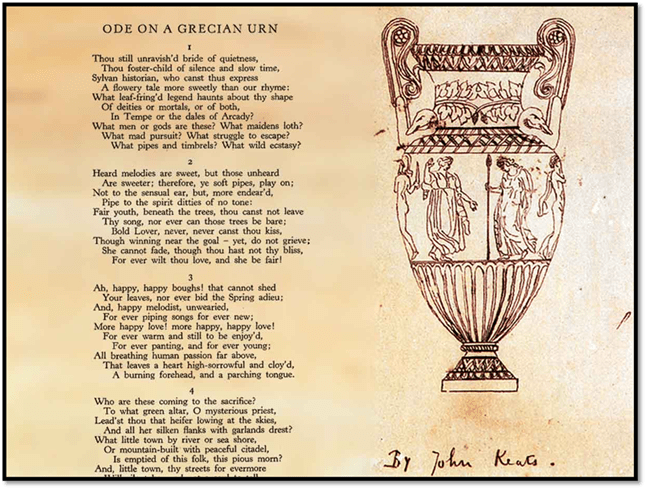

We tend to like action in our stories, whether of the epic sort from Homer’s The Iliad onward but an aim of some artistic forms, even some literary ones, has always been to capture stillness. Even a medium that relies on motive force operating in the field of passing time like music may aspire to stillness, wherein silence and motionless are evoked. In poetry this is often created through evoking the ambiguities of the word still – suggesting something that remains as it was continuous from the past, something in which motion seems stopped and something silent. All those meanings played around the increasing repetition of the word ‘still’ in Wordsworth’s ‘ Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey’ It reverberates through lines that evoke discontinuity, motion and sound all ‘stilled’ by the placing of that word in the music of the lines and haunting its contradictions of meaning. However the greatest poem of stillness in English – into the Germans mastery we ought not to tread – is Keats’ Ode On A Grecian Urn.

Suggested by Keats’ view of the Elgin Marbles, he chose to represent Greek narrative visual art in an imagined urn telling some of the same story as the bas relief sculptures he saw that had once adorned the Temple of Athena in the Acropolis. Therein the first line sits the word still – actually signifying the endless delay of the sexual action that will ‘ravish’ the Grek virgin – it is equated with the evocative moment of a stillness in action and motion and silence – a;; these meanings piling on in the nest few lines to retrospect on that stillness

Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

A true stillness, like that in Wordsworth is one where the energy that drives motion, action and noise impels the imagination to continue what the artwork ever seeks to hold still:

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Of course stillness has a cost – the cost of not experiencing the joys of mortality and mortal being any more than its pains.. We are ‘ For ever panting, and for ever young’; in a pleasurable state nevertheless never reach the everyday consummation of our passions, only the drive of their internal appetites. The whole problem of artistic form is that it is a ‘silent form’ that ‘dost tease us out of thought’ but which nevertheless witnesses to eternal never consummated ‘marble men and maidens overwrought’. That word ‘overwrought’ does some work in suggesting the frustration we see elsewhere in the poem in its evocation of fleshly motives and anxieties whilst it indicates merely artistic work applied to produce the artistic form.

Not for a moment do I see Adrian Duncan as indebted to Keats. He is rather returning to the basic questions that artistic form poses to its makers and subjects, who remain .temporal not eternal beings – exposed to the excitements and troublesome quests the world demands of us as people as well as to the effects of time where things get continually lost, not only objects but the memories thereof, as if predicting the ends which predicate time’s meaning: whether these ends be goals, achievements, failures, change of direction, fatigue or even death. The idea of the ‘overwrought’ is crucial to this novel as we shall see – containing in it a sense of the vulnerabilities, frailties and the lack of integrity humans as raw materials always bear that haunt their projects great or small. And one of these projects is art itself: a thing forever hinting at the transcendent but actually made up materials that like all real things are flawed and largely vulnerable to breakage.

Tennyson felt this even about the language he used as well as the paper on which the language was written. Mourning a great loss in Arthur Henry Hallam he wondered if poetry itself were not a project doomed to failure as his death sometimes made Hallam’s existence feel:

What hope is here for modern rhyme

To him, who turns a musing eye

On songs, and deeds, and lives, that lie

Foreshorten'd in the tract of time?

These mortal lullabies of pain

May bind a book, may line a box,

May serve to curl a maiden's locks;

Or when a thousand moons shall wane

A man upon a stall may find,

And, passing, turn the page that tells

A grief—then changed to something else,

Sung by a long forgotten mind.

It is not only that the meaning of the poet and his love will have changed but the paper on which words are printed will be used to bind another’s book, or worse by used as rollers for ‘a maiden’s locks’, as objects of vanity as it were. The Gorgeous Inertia of the Earth does not even in its title propose to examine what is still, and quietly passive but what is ‘inert’, lacking all dynamism and the power of motion and action. Hence, its characters all aim to study statues and buildings, even their ruins and reconstruct them out of memories constructed as if from within them. Can, or should art move us, to the point that it itself moves again, or seems so to do. And here we deal with not just great art but that of lesser makers who jostle around the pinnacles of great names, and some confusingly invented names, like the artist Schmid, the sculptor in the novel of the dual figures of the Romantic married poets Achim and Bettina von Armin.

Europe is littered with memorials to the couple, as it is with Walter Scott. I looked everywhere for a version by an artist called Schmid but found none. I found a Karl Schmid but he was a sculptor of an altogether different orientation to the one in the novel, though both have tragic backstories which make them contemplate how to lock unions of people in dual sculptures together to make these unions less vulnerable. The nearest to my imagination of the sculpture that the narrator of this novel, John Molloy, and his co-worker and later wife, Bernadette, see and study together is a sculpture not in a city with a name starting in ‘I-‘ like the one in the novel but one in Berlin by Michael Klein (see the collage and caption below).

Klein, Michael (Sculptor) 1996-1997, Monument to Bettina and Achim von Arnim – Sculpture in Berlin (1979), Arnimplatz, near Paul-Robeson-Straße / Seelower Straße. On the north side of the large inner park roundabout of the square, which was named after Achim von Arnim in 1903, the rectangular plinth of a monumental two-figure bronze sculpture rests on a mighty rectangular and two-tiered base made of polished travertine. The group shows a human couple sitting on a stool in an interlaced arrangement. The figures each have an outstretched leg and a pulled or bent leg. The smoothed, partly summary formulation increases the monumentality of the sculpture in addition to the dark patination of the bronze. The poet couple Bettina and Achim von Arnim are depicted in sparsely hinted contemporary clothing and hairstyle. On the plinth edge on the right, the signatures of Bettine Arnim and Achim von Arnim can be read in cursive letters. On the right side of the stool, a round plaque can be seen raised (Jörg Kuhn, Susanne Kähler). https://bildhauerei-in-berlin.de/bildwerk/denkmal-bettina-und-achim-von-arnim-7170/

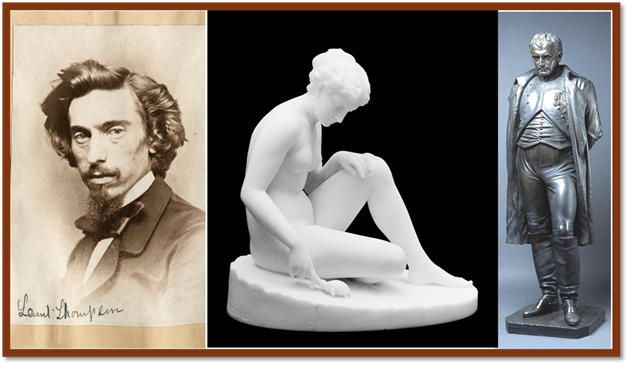

It is by no means a great statue I think though neither are many that John contemplates though many are extremely well known. Some seem little more than kitsch such as the work of Launt Thompson, who comes in for some of the most interesting theorising about sculpture in stone in the novel.

Launt Thompson: ‘Unconsciousness’ and ‘Napoleon I’

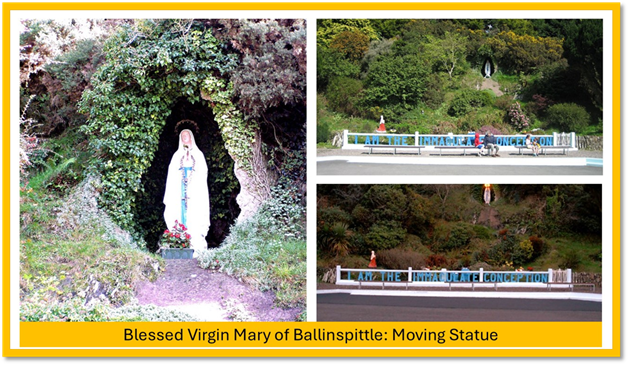

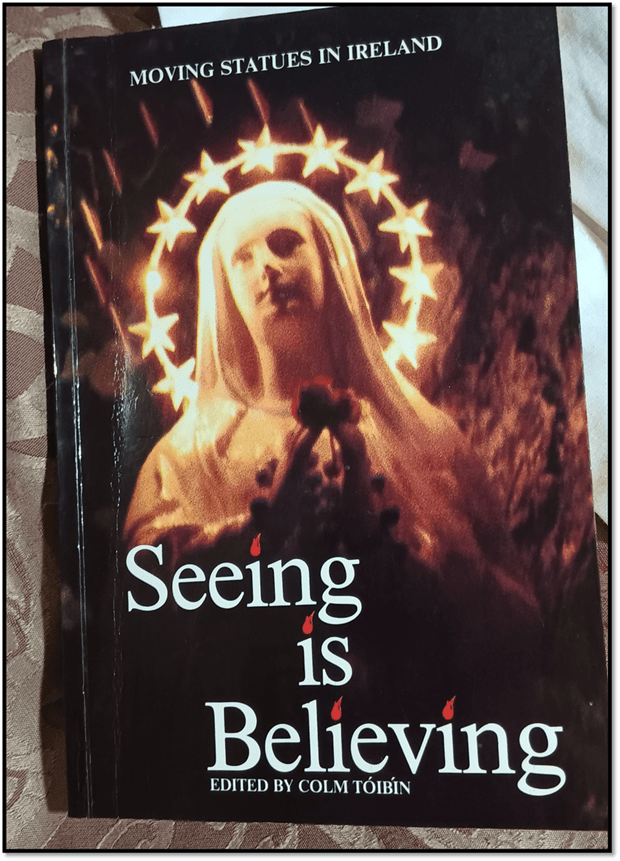

Indeed at the ‘heart’ of the novel is an even more kitsch statue – the most notorious but not the first of the ‘moving statues’ of Catholic Ireland, the Blessed Virgin Mary of Ballinspittle, a village not far from Cork in Western Ireland.

Playing amongst works rarely considered as of a high degree of artistic achievement is important to John Molloy and Bernadette for their view of the art is less to do with the judgements of a connoisseur, values so often very quickly translated into monetary ones but to the abstract idea of how art works with the raw materials it metamorphoses. Both are concerned with the making and viewing of art in association with rituals of religion and those that consecrate the passage of time move backwards in memory and as progressing to the art’s future – even that of possible neglect and ruin, much more likely one might think of Launt Thompson. Their models of art being the victim of timely and human degradation are not ones whose quality is doubted. Nevertheless they are ones vulnerable to loss in particular. John makes models of pieces he knows to study them. One such is a model of a caryatid from the Athenian Erectheum (now served by copies – see the collage below on the left) on the Acropolis.[3] But out of all the ones he can study, he chooses not those still preserved in Greece ny the one the Greeks still describe tas the missing caryatid – the one bought or stolen, based on your readings of Lord Elgin’s negotiation with the Turkish Ottoman overlords of occupied Athens at the time. John calls it the ‘Elgin caryatid’, for which there is a vacant place in the Museum at Athens (centre in the collage below), whilst she stands pretending to be integral to the architecture In the British Museum.

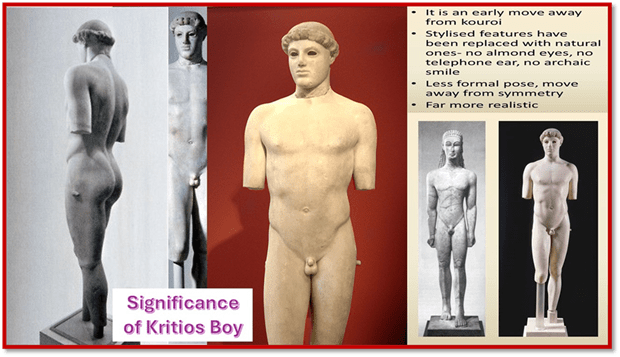

The other is the Kritios Boy rescued from total loss of its significance by its reconstruction from various pieces found on the Acropolis over a vast period over a long period before its significance was heightened by art historians. Even the style of the step and stance of the piece, the contrapposto, was attributed as first in this piece although this feature is not as different from the ancient models of the temple kouros (a male figure originating in Egypt) as other features. But for John, the issue is the vulnerability of the boy, marked in those pieces of him still unfound. It is as if, he says, those lost fragment ‘were portals into the mystery of this form’ this view of Earth, and the distant thoughts of his maker’.[4]

Kritios Boy. Marble, c. 480 BC. Acropolis Museum, Athens by User:Tetraktys and one more author – Own work. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kritios_Boy

This is a fascinating moment in which the secret of form – attached so intimately to, it seems, so much other knowledge of what creation means in the mind of maker and made. The analogy of all this obscure lost knowledge is that the figure ‘is thought to be the first instance in sculpture where motion was successfully suggested’. And here we have it. The most mysterious thing in stone statuary is that moment wherein we see the perfection of both motion and stillness as if both were simultaneous, even though they are considered contradictory.

Sculpture in the text, in style as well as substance if they can be distinguished which I think not. of this beautiful novel is made to bear the burden of this desired truth, as if in being crafted and wrought – sometimes ‘overwrought’ as some of them are, at least in their ruined state – motivates to action and motion just as much as it then calms and stops and stills all motion and action. Just after we are told of the Kritios Boy, John remembers from his ‘mid-thirties’ seeing the world of Launt Thompson ‘in the flesh’. Languishing in thought over Thompson’s Unconsciousness (see above – it is a young woman toying with a turtle) he works out from the backstory of this commission a meaning that nevertheless supports what he already thought, because he’d:

interpreted her posture as a pensive kind of waiting in the in-between moment of her wedding night, and I read the turtle as here merely toying with the end of her childhood.[5]

The juxtaposition in this moment of a stillness of waiting with the excited preparation for an event of sexual consummation is totally that of Keats’ ‘still unravish’d bride of quietness, / Thou foster-child of silence and slow time’. It is what Bernadette seems be thinking too about time’s passage in the letter from her he is reading at the same time (her italics): ‘When did we stop believing in the life in motionless things?’

Contrapposto is not important as a milestone in the achievement of a more realistic capture in art of life but as a kind of incarnation where, to John, the Kritios boy seems ‘magically about to step towards someone or something that has caught his eye’.[6] Stepping forward later becomes emblematic of how John begins to accept his own naked body as it looks in the eyes of someone who might love him and lets him embrace a more fluid and less death-laden life in the flow of ‘cool and oily water. When John accepts Bernadette’s invitation to ‘’expose’ his body its fleshly and living state, it is as if he is emerging into life from stone like the Kritios boy. Read the following extract. The end of Part I of the novel to shee how ‘stepping out of something that has encapsulated me for some time equates him somehow with his most magical perception of moving stone – the Kritios boy or the Virgin of Ballinspittle. Flowing water is a symbol of life, and resurrection throughout the novel – the tracing, for instance of the buried river L’Aposa under the ground of Bologna and even its weighty Cathedral.[7] It recalls the water Moses drew from a stone in the making of the Covenant with the migrant Jewish people in the ‘subtle fountain in the Piazza Cavour: “ water sprouting from a rock”.[8]

My Photograph of page 102

If life and motion can be captured in a form that to most is considered still and passive to actions by others, then we achieve something great; we absorb into ourselves a ‘belief’ system that means that both the object and subject of art is not the raw materials transformed into a pleasing object but is the essence of created life itself- a life pregnant with the eternal stillness that reminds us of death but is not death though equally without a further end. In a sense this is why the whole story is a contemplation by John Molloy of his own mother’s vision of the motion in an statue in Ireland, her incarceration in an asylum for that belief and his attempt to understand why motion and life can be seen in dead unmoving stone that has been subjected to idealised creative influence. John even tries to use Bernadette’s still-held Catholic belief to further resurrect what his mother experienced and what he might yet experience. When asked to share the visual content of the experience of her faith, Bernadette says: “That place is only for me, John”.[9]

Forced to experience the place where stillness and motion exists simultaneously John is forced to the epiphany of Saint Cecilia at the end of the novel, but even here he refuses to see the visual evidence and this is perhaps characteristic of belief for John. It belongs not to sight but to dark inner revelation. I think, for instance of that moment when he sees a man in Bologna genuflect at the portal of the Cathedral and he turns to see ‘what he can see, but the innards are shrouded in a complicated darkness’.[10] Perhaps in the end we have to grow enough to see that what covers mystery – a complicated darkness is all we can expect to see.

The mystery the novel starts with is the puzzling unity between Achim and Bettina von Armin. Bernadette and he are ‘studying this sculpture to better understand its form’.[11] The mentor of the EU-funded project wants from it ‘a “history from within” of’ the sculptures.[12] It is this objective that appears to launch John and Bernadette to seek the truth that can only exist inside rather than outside objects and their visible relationships. The two know that this search for meaning requires a curiosity about life and art that is discouraged in the academic drawing class at art colleges. Attached to such a curiosity is a faith in the processes of non-analytic making; a belief that artistic form evolves not from the application of techniques learned in the academy but from having faith that the use of broad marks on paper to demarcate light and shadows and lines that can be changed to ‘help the drawing find its own form’.[13] This trust in what comes from within is essential to the aesthetic, psychology and the meaning of ritual action in the novel. And ritual action covers even everyday perceptions of others of the complexity of the subjectivities in interaction.

The capture of moments of motion in stillness are especially involved in such issues and this explains why so much of the novel is obsessed by passengers in transit in a train. Sat in stillness the pace of events happens around people through train windows. The finesses of Duncan’s sentences is particularly good in these sections but I hesitate to analyse them fully here, although Chapter 7 would offer great opportunity for this – if not the only one. However, so concentrated would need to be the attention to the sentence structures in these passages of transit through time-space I hesitate to commit.

An easier example is the slow motion of the ritual supplication of Bologna monks in the cathedral the space-times it transitions. We observe ‘four young monks’ who ‘drop to their knees’ until ‘a sort of stillness comes over them – four rocks on the shore of a vast waterless lake’. Drained of all fluidity even the cathedral is ‘now stunned into stasis’. It takes a live monkey sitting on the head of a stone San Vitale to break this stilling, and drying out, of all life. Art or meaning in life outside of the stony permanence of death will not occur until flow and stasis, stillness and motion united. Time moves strangely in this novel. Between Part I and II John ages from a young man contemplating his link to Bernadette to the 56 year old now married to her and relating to her now grown daughter, Philomena. In that interim his old lesbian friend Anna, the repository of his faith in the meaning of ruins and their imaginative reconstruction, loses her lover, and her faith in her work with stone, and dies slowly in pain during Part 2 with her new lover, Patricia. Such a diffusion of the author’s obsession is allowed to be collapsed in the predictive sequence of time-space transit that is a train-journey. When a ‘ruin comes and goes’ we are viewing them from a speeding train but it is also a putting-into perspective of John and Anna’s life-work. Read the whole passage to feel the strength of the writing of this feeling of being overwhelmed in creation and destruction both.[14]

I tire of writing now but this blog must be completed tonight for I have no blog with which to substitute it. Yet a mere line cannot be drawn at this point for I feel a need to carry my own learning in this novel to some optimal level. This involves returning to its main burden, which is that meaning of art lies not in its imaginative reconstruction alone but in living inside the processes of creation and destruction (and all and ruin of course) of art itself. The novel starts with the challenge to tell the history of specific sculptures ‘from within’ to get at the mystery of their form but it never shows how this story must be told. But form is born from specific material and John himself invents a series of categories by which to classify the materials he uses in his own models and which are used in the sculptures themselves.

He calls them ‘a taxonomy of stone’ or a ‘taxonomy of rocks’. Which is based on a series of characteristics against which each stone or rock is tested.[15] Various examples are given of rocks starting with Basalt but eventually reaching through, for example, Granite and Limestone to Marble and Hornsfels.[16] The main qualitative categories of the taxonomy are ‘Structure’, ‘Strength’ and ‘Breaking Pattern’. My sense of this taxonomy is that describes, even despite its apparent objectivity, a description of different degrees of strength and vulnerability, where ‘breaking patter’ stands for different kinds of disintegration – by fissure, cracking, crumbling or other means. And the novel then becomes for me a journey inside hard exteriors to search the vulnerability within to stress, including those contingent on time and productive of ruins that ‘come and go’. Bernadette even proposes to John the question of whether he began to ‘study stone restoration’ because of his experience of personal fracture – a ‘leg injury’.[17] But it is not only hard material things that crumble, crack or fracture but inner selves too. The model that John makes of the von Armin couple has detected in it a ‘hairline crack’ that splits the form of Bettina and then threatens that point where ‘her back meets Achim’s chest’.

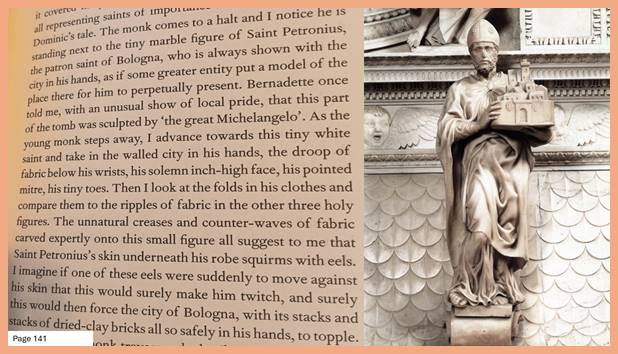

Everything people value – relationships, art, social life – the notion of the community or city of God even – can and does break. John witnesses this in the fragility of the Bologna Saint Petronius – a statue threatened by movement from within so much – movement very typical of Michelangelo the novel seems to propose. There is even humour in the fact that the writhing eels under Petronius robes make him fear the fall and rupture of the community of God on earth- the Cathedral:

People split, fracture and crumble and so do relationships – the novel continually posits these things as vulnerable to time and agencies the operate in time including death and subjective responses to death. And look at how John describes working in stone, describing the carver of stone as a rupture and embalmer both.[18] John hates to contemplate a memory of a fainting boy’ later lest it was he that fainted. As he contemplates Anna later on her death bed (in imagination only), that process is like entering into stone:[19]

Inner worlds crack, crumble and rupture too like stone. The most unresolved vulnerability in John is his memory of his mother’s vision of a moving statue in rural Ireland before such visions were common. Her commitment to her inner vision of moving stone led to her incarceration and marginalisation – to a vulnerability oft repeating in John and his relationships of love, sexual passion and friendship. Duncan has clearly studied this phenomenon and references a 1985 book referring to Ballinspittle, the time of many visions of moving statues. In his Acknowledgements here mentions that Colm Tóibín edited the book but does not mention that writers book on Moving Statues in Ireland, which he must know. All I take from this is that both writers move into a dense area where psychology, belief, memory and perception blend with history and biography and fractures are seen in their attempted cohesion.

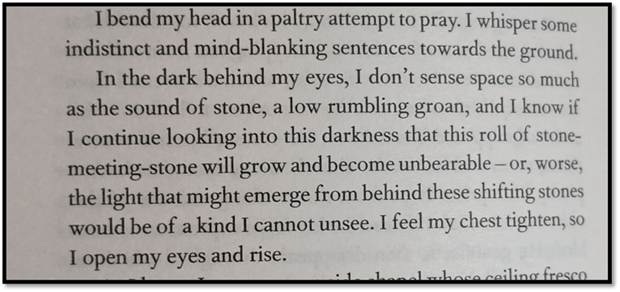

In John, his memory of his mother is so full of fractures made from guilt and pain that at the end of the novel he refuses to look to see whether the statue of Saint Cecilia in the cathedral at Bologna is looking at him and in some kind of motion, though he feels it must be lest ihis experience approaches too near that of his mother:

…I cannot dare to look. I sense her mouthing something to me from her chamber, … a request for me to return her gaze … I realise these things she mouths, though facing away from language, still disintegrate meaningfully into the realm of silence.[20]

The juxtaposition of ‘still’ and ‘disintegrate’ near the idea of an articulate silence contain the burden of the novel but it is the context of a man who must not see the contradiction but only feel it in order to be safe; as he has already said: ‘If I were to pray, it would be for this figure not to move, to give me no sign of life and to stay motionless forever’.[21] Instead he prefers a ‘theatre form of devotion’; a reference I will leave for others to ponder.[22]

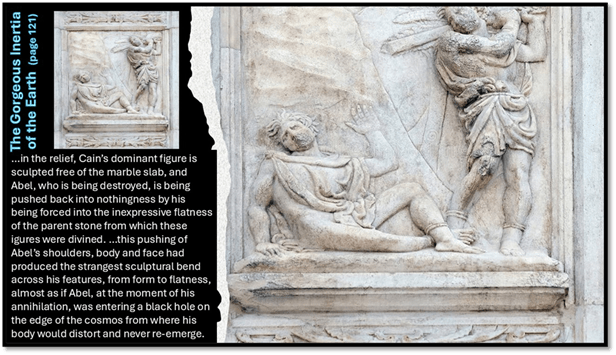

Nevertheless, if the novel moves into this moment of rejection of vision for inner feeling, it certainly illustrates on the way to that rather negative goal. John’s favourite kind of sculpture and sculptural modelling in his study is bas-relief. I sense this is because such forms require the form and ground, the figure and context to be a constant dramatic interaction, especially as this forms require more than one figure to be meaningful. A favourite passage of mine is this describing a bas-relief of the story of Cain and Abel.

…in the relief, Cain’s dominant figure is sculpted free of the marble slab, and Abel, who is being destroyed, is being pushed back into nothingness by his being forced into the inexpressive flatness of the parent stone from which these figures were divined. …this pushing of Abel’s shoulders, body and face had produced the strangest sculptural bend across his features, from form to flatness, almost as if Abel, at the moment of his annihilation.

This passage is like an allegory of the drama of characters who use their relationship to each other to perform, by projecting it into a social scenario, the existential angst of their human conditions. We are either strong like Abel and an agent of change in others or like Abel destroyed by our failure to choose an arena in which to perform our being. In the process we are reduced to ‘parent stone’ akin to ‘annihilation’ and the very structure of our identity makes a ‘sculptural bend’. This is very powerful.

It is late now and I must end here and publish this blog lest I fail to do that for today and my blog count return to zero – the WordPress method. I do not though think I could have completed an argument about this novel of fractures that wasn’t itself fractured and broken. I could perhaps have proof-read and revised but any urgent concerns here will have to wait the morrow. Meanwhile, do read the book as your first priority. Here is a writer of a very extraordinary kind.

With Love

Steven

[1] Adrian Duncan (2025: 15) The Gorgeous Inertia of the Earth London, Tuskar Rock Press

[3] Erechtheion[2] (/ɪˈrɛkθiən/, latinized as Erechtheum /ɪˈrɛkθiəm, ˌɛrɪkˈθiːəm/; Ancient Greek: Ἐρέχθειον, Greek: Ερέχθειο) or Temple of Athena Polias

[4] Ibid: 16

[5] Ibid: 22

[6] Ibid: 16

[7] Ibid: 155 & 174

[8] Ibid: 134. See Exodus 17, verses 5-6: ‘(5) And the Lord said unto Moses, Go on before the people, and take with thee of the elders of Israel; and thy rod, wherewith thou smotest the river, take in thine hand, and go. (6)Behold, I will stand before thee there upon the rock in Horeb; and thou shalt smite the rock, and there shall come water out of it, that the people may drink. And Moses did so in the sight of the elders of Israel”.

[9] Ibid: 152

[10] Ibid: 132

[11] Ibid: 4

[12] Ibid: 7

[13] Ibid: 10

[14] Ibid: 94 – 95

[15] Ibid: 14

[16] Ibid: 20, 55, 63, () &163

[17] Ibid: 48

[18] Ibid: 32

[19] Ibid: 116

[20] Ibid: 208f.

[21] Ibid: 196

[22] Ibid: 200