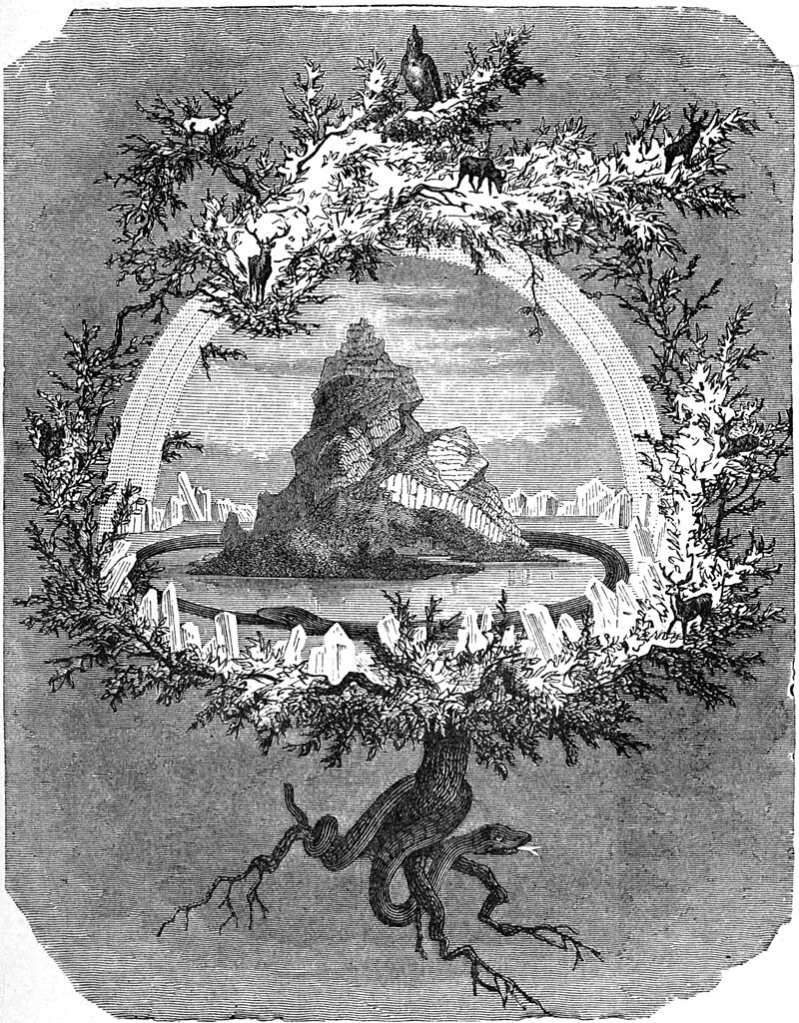

In Nordic mythology the Tree of Life, Ygdrasil, connects past, present and future of a culture or bloodline but is also a symbol of eternity and divine intelligence. Above is Heine’s emblem that had sinister uses for the Nazis.

Words have a right to change their meaning and their method of doing so is to be used very loosely. Such a word is the word ‘tradition’. It is a word bound up in theology, particularly Jewish and Islamic theology, representing those parts of the revealed truth of God that were never written down in some original text but were handed down orally and in practices (or rituals) and then collected as handed down. That meaning emerges in relation to Christian liturgy in the fourteenth century. Its use in Western knowledge of Eastern religions is attested in an early recording of it in 1718 according to etymonline.com: ‘Used by 1718 in reference to the hadiths of Islam and doctrine supposed to have been revealed but not written down’.

I was taught by Professor Randolph Quirk at UCL many years ago.

The word tradition has been problematic from the start, though I think this is not even loosely acknowledged in the prompt question. It derives from the Latin and from the Latin word transforming through its usage in old French. Etymonline, again, has the primary meaning (that which is supposedly referenced in our question) thus:

tradition (n.) : late 14c., tradicioun, “statement, belief, or practice handed down from generation to generation,” especially, in theology, “belief or practice based on Mosaic law,” later also of Christian practice, from Old French tradicion “transmission, presentation, handing over” (late 13c.) and directly from Latin traditionem (nominative traditio) “a delivering up, surrender, a handing down, a giving up” (also “a teaching, instruction,” and “a saying handed down from former times”).

However the word has a double nature precisely because it can mean both ‘handing down’ via a legitimated route OR ‘handing over’ by an illegitimate route. The first meaning (of legitimate sharing and passing on) involves institutionalised routes of transmission such as family but is also used of more circumspect trans-temporal groupings, such as bloodlines and ethnic nationhood. The second meaning is that of handing over to an illegitimate other – another family, nation or bloodline, a thing of value that the original institution wants to keep to itself either as a possession or ‘sacred’ knowledge. This is why etymonline says the word is a ‘doublet’ of the word ‘treason’:

The senses of tradition and treason still overlapped as late as 1450s, when tradition could mean “betrayal,” and Middle English traditour was “betrayer, traitor.” Traditores in early Church history was the (Latin) word for those who during the persecutions surrendered the Scriptures or holy vessels to the authorities, or betrayed brethren.

So beware our prompt. In one sense, it means: what actions or beliefs have your family passed down or share with each contemporaneously? However, in another it means – commit Treason! Tell your family secrets to the whole world, share them with non-believers and naysayers.

No word then is innocent of other meanings, however unknowing the speaker may be of those meanings. If in ‘the fine arts and literature, “the accumulated experience and achievements of previous generations.”‘ (etymonline) is whatbtradition is, T.S. Eliot’s uses of it had to my ear a fascistic ring that probably would appeal to Donald Trump’s ‘common-sense’ versions of what is necessarily ideological racism and nationalism. You would not guess so from this passage from his essay Tradition and the individual Talent with its august untranslated reference to Aristotle’s On The Soul (a fuller text of the whole can be read at this link) however:

δ δε νους ισως Θειοτερον τι και απαθες εστιν [1]...The emotion of art is impersonal. And the poet cannot reach this impersonality without surrendering himself wholly to the work to be done. And he is not likely to know what is to be done unless he lives in what is not merely the present, but the present moment of the past, unless he is conscious, not of what is dead, but of what is already living.

That interplay of the living and the dead is Eliot’s view of Tradition: it is the oft unspoken beliefs and practices of the now dead passed down and given life again by the living. This is as much and as little as Eliot means by ‘tradition’ being impersonal – not bounded up in the life of an individual person. Hence the invocation of the Greek term νους (nous), which whatever its meaning through history, for it mattered greatly in medieval times, was always above all, IMPERSONAL.

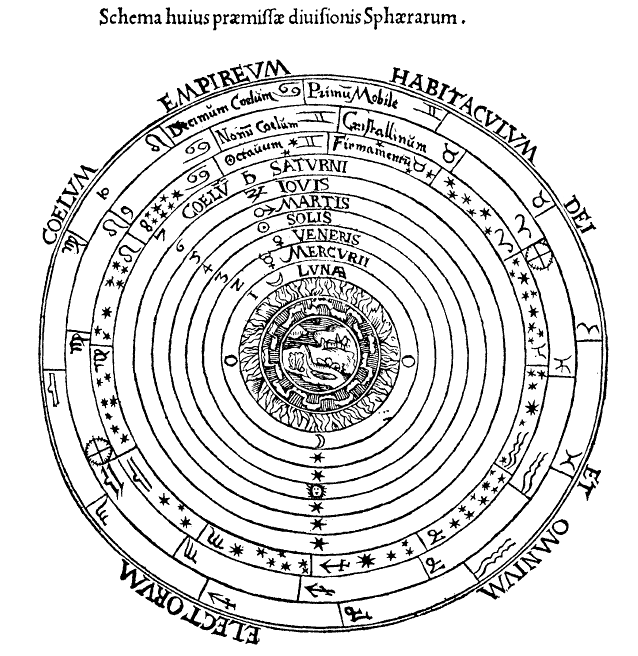

This diagram shows the medieval understanding of spheres of the cosmos, derived from Aristotle, and as per the standard explanation by Ptolemy. It came to be understood that at least the outermost sphere (marked “Primũ Mobile“) has its own intellect, intelligence or nous – a cosmic equivalent to the human mind. Fastfission – From Edward Grant, “Celestial Orbs in the Latin Middle Ages”, Isis, Vol. 78, No. 2. (Jun., 1987), pp. 152-173. See also: F. A. C. Mantello and A. G. Rigg, “Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide”, The Catholic University of America Press, p. 365 (on-line text here). Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nous#/media/File:Ptolemaicsystem-small.png

In as far as this relates to poets, all well and good. The Waste Land of 1920 is a poem that continually quotes poetry from past traditions to show contemporary twentieth-century audiences how cut off they are from them, and how much they need to reconnect with them beyond the fragments in the poem to save us from a too personal poetry (which in some sense The Waste Land is). But how innocent is Eliot’s view? Look at the passage from his After Strange Gods, (a work that is one of the evidences of the tendency to fascism of European modernism) that etymonline chose to quote, and the idea of ‘tradition’ is generalised to national politics in order to talk about the traditions of a nation as those of a bloodline (just as German fascism had valorised the traditions as the bloodline inheritance of Aryan races and established racism (and especially Antisemitism) at its heart):

What I mean by tradition involves all those habitual actions, habits and customs, from the most significant religious rite to our conventional way of greeting a stranger, which represent the blood kinship of ‘the same people living in the same place’. … We become conscious of these items, or conscious of their importance, usually only after they have begun to fall into desuetude, as we are aware of the leaves of a tree when the autumn wind begins to blow them off—when they have separately ceased to be vital. Energy may be wasted at that point in a frantic endeavour to collect the leaves as they fall and gum them onto the branches: but the sound tree will put forth new leaves, and the dry tree should be put to the axe.

The idea of tradition as a tree that can be ‘sound’ as a bloodline or ‘dry’ is eminently fascistic. A dry tree needs o means to kill it off: a weapon or axe (like Siegfried in Wagner) that might exterminate traitors in a final Holocaust. If we need to be true to tradition, it is easy to see how not being so is akin to ‘treason’ and might merit incarceration, exclusion or state murder – even genocide like that modern Israel was so keen to inflict on Gaza. That is the downside of the tree metaphor for life. The Tree of Life, known as Ygdrasil in Nordic mythology,, can be a tree of racially cultural survival and dominance justifying Nordic incursions amongst subaltern races.However the Tree of Life may be said also to assert the dominance and priority of ideas of mind and soul over what local cultures consecrate as their own Gods. This to me is the meaning I take from Odin’s virtual crucifixion and death in war with Ygdrasil:

.

However modern myth-makers read the Life-Tree a a global phenomenon to which local Gods have to bow down. Odin is, as it were as I said above, crucified on that Tree indicating how supremely confident ideas of divinity must be of their lesser value than the principle of the Life of all systems a of living combined and their organic equivalences of flora and fauna. A..S. Byatt in her fine fable of ecological disaster, in my view the best ever written or passed down, Ragnarok makes Ygdrasil a phenomenon on which all lives in all its diversities – human and otherwise – relies. In an essay attached to her novella-fable, she says that myths are not necessarily pleasurable things to live with:

Myths are often unsatisfactory, even tormenting. They puzzle and haunt the mind that encounters them, They shape different parts of the world inside our heads, and they shape them not as pleasures, but as encounters with the inapprehensible. (My emphasis from A.S. Byatt (2011: 161) ‘Ragnarok: The End of the Gods’ , Canongate, Edinburgh)

In a doom-laden earlier blog (at this link) where I first quoted that Byatt passage, I stated, in that oracular tone I often feel ashamed of, that I thought the time for hearkening to scientific argument for fighting global climate change and species decline was probably passed. However, if that is so, I am no more hopeful myths that can prove even less effective. Who, after all, even knows of the art and thought in Byatt’s Ragnarok? In that blog, I wrote:

… we fail ourselves if we merely use information about climate change, global ecological metamorphoses or the extinction of species in the face of the degradation of their habitats as data with which to write an essay or file a report. We even miss, in that case some, of the associated or collateral damage. Simon Schama, for instance (see note 2 below), insists, that is not just species extinction we should fear but also the arrival of new – or, as is more likely revivified – viral life-forms of which Coronavirus may or may not be one. If we are to write, let’s write a piece as aware of the threat as a book like Simon Schama’s Foreign Bodies, writing as an historian and A.S. Byatt’s novella Ragnarok, based on the imagination of the doomed ecosystem we inhabit. She mythologises the fate of that whole ecosystem (in order to more deeply inform us) in the story of Yggdrasil, the Life-Tree (see The Guardian’s review at the link immediately before this). [2]

Trees are a tradition as august as any handed down to us and our reverence to them ought to be held in some awe – by which I mean fear as well as reverence. The Tree is the most universal of symbols. Yet the size of global afforestation is declining as a direct consequence of the globalisation of capitalist ethics (or lack thereof) and power inequalities within nations and cultures as well as between them. The august, even revered, symbols persist in the writing of ancient worlds.

The Judaeo-Christian version of the Tree is one of the Knowledge of Good and Evil and in traditional beliefs, though it contributed to the Fall of humanity, it, also, as the wood formed into the Cross on which Christ was crucified, participated too in the story of human redemption. But however dense with meaning, feeling and prompts to action such myths and symbols are, to say nothing of the persuasion of what Greta Thunberg calls ‘the science’, we, as modern peoples, think that thin representations of our reverence for trees that only stay inside the mind are enough – for those don’t forbid us from cutting down real trees. Of the tradition of trees, even those in the dead metaphor of that symbol of tradition and handing both downwards and laterally, THE FAMILY TREE, I think the evidence is that they are held only notionally in the head and not deeply in the heart. The tree, like other traditions, has been betrayed and is the victim of treason rather than of tradition: we don’t care to whom we hand or deliver it.

And I think that is the issue of which this WordPress prompt is a symptom. T.S.Eliot would mourn the fragmentation of our links to the past and the dead this betokens in summarising our contemporary life. I could answer this question by speaking of family links, where all generations of a Jewish family, meet at a meal celebrating the oncoming of Sabbath (a ritual with deep roots) or a family for whom is is traditional for all the men to go to the pub on a Sunday morning whiles wives cook Sunday dinner, or even things some familes call a tradition but are quite recent – like: ‘Evey Thursday we traditionally go to the cinema in the evening’. You can’treallyy betray or be traiorous to such traditions, except the first perhaps. Indeed, one of the most popular recent TV gameshows, Traitors, is based on the glee of us as watchers seeing traditions of group loyalty betrayed with cunning.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2xRtJpWRbKcwPdXs7bZnxxH/the-traitors-how-the-show-works

I think all of this is a good thing, for traditions need to be true not pleasing, and, as Byatt says, like myth, inapprehensible in part because they constitute that about which we must have faith and loyalty that can be betrayed. Family, especially the notion of the biological family (often extrapolated into communities of biology or ‘races’), are thinner myths in truth today than they were once. Families have always existed as tools of tradition, but only if you accept that treason is part of their DNA. The greatest literature on earth has always been about this: The Oresteia, Oedipus Tyrannus, Antigone, King Lear, Hamlet, The Leopard, and the whole of the work of Colm Toibin.

So why shouldn’t we today see ‘traditions’ as something you merely choose to favour and that can be passed on to others without betrayal. We may try to ensure no harm comes to.our family by only passing on the trivial traditions. But maybe that is all tjere os now anyway! Modernity asserts that traditions need not be long-lived and validated by older forms of thinking, feeling and acting. This can help us to see that the family that works best is not the biological one of irrational bonds and responsibilities but chosen families in which the mix of the irrationl and rational in that choice can be negotiated and may vary without guilt.

So:

What do I have to say about a few of my family traditions?

The tradition Geoff and I follow is to choose to whom we gift our loyalty and trust, or versions of that which we allow to vary in respect FOR the people that are chosen’s own choices or because of fundamental breakdown of trust on either side. And we will keep on choosing, sharing love between the chosen. The chosen are not an elect, as in religious tradition or old families, where bonds in biological families, at least thus far in history, have to be irrational, but ARE people open enough to love each other without the necessity or command of judgement. The tradition is:

Oh come, all ye faithful (always admitting that faith is a variable and not a demand on the other) Joyful and truiumphant (for I do not bind you by thinking that to honestly seek closure with respect is A BETRAYAL).

We can learn a lot about how past loyalties were structured from some etymologies. Remember this one:

The senses of tradition and treason still overlapped as late as 1450s, when tradition could mean “betrayal,” and Middle English traditour was “betrayer, traitor.” Traditores in early Church history was the (Latin) word for those who during the persecutions surrendered the Scriptures or holy vessels to the authorities, or betrayed brethren.

My God may not exist, but they/it save(s) me from treachery being the real meaning of my family traditions.

Go in peace and with LOVE

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________________________________

(1) Aristotle, On the Soul 408b: “Presumably the mind is something more divine, and is unaffected” (for context, https://www.loebclassics.com/view/aristotle-soul/1957/pb_LCL288.49.xml).The translation may disguise the difficulties of understanding the way the Greeks, and Aristotle himself, used the word νους (Nous).

[2] For Simon Schama’s assertions and evidence on the link to viral revival in the face of ecological change, see Simon Schama (2023:1-19) Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines and the Health of Nations London, Simon & Schuster. This is a footnote from my blog: https://livesteven.com/2023/09/22/is-ragnarok-on-its-way-it-is-but-if-we-knew-that-and-were-fully-informed-by-that-knowledge-we-would-be-urging-governments-to-act-and-now/