The queer artist, Charles Ricketts, wrote: ‘There is something Latin in the fibre of Titian, in his sense of reality and sense of control. … he belongs to a patrician people to whom experience is met by the force equal to control it’. [1] Could such a judgement relate to the experience of queer life in a Britain certain of its imperialist pretensions?

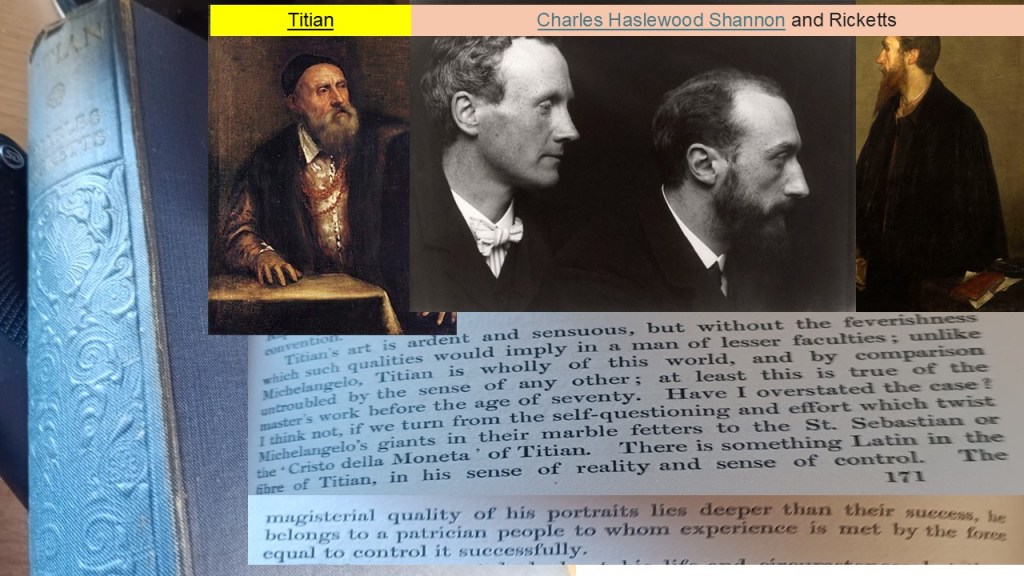

As I flashed about for subjects for my blogs, I turned today to a book I have been meaning to turn to when I acquired it, thus motivated by seeing an exhibition of the work of Charles Ricketts and his lover, Charles Shannon (who lived together with him in London) at the Tulley Museum in Carlisle. The work of this queer artist, and his ‘husband’ sorely needs looking at seriously again I think, but meanwhile I glanced over his book (and its 181 monochrome plates), concentrating on his summary of the great Titian’s achievement in Chapter XXIX (‘Conclusion’).

I was arrested by a paragraph – in full in the collage above, with an excerpt in my title, where Ricketts compared Titian to the emotional ‘self-questioning and effort which twist Michelangelo’s giants in their marble fetters‘ to Titian’s stoic version of the queer icon paintings of Saint Sebastian. I have before tried to query Titian’s painting myself in terms of for its homosomatism (my invention of a concept for a queerness that all might identify in themselves with labelling themselves) but this perception of Ricketts has much more to do with the writer’s suspicion that the distortion of great souls, especially great queer souls, by the tortuous body-twisting demands of the Christian religion.

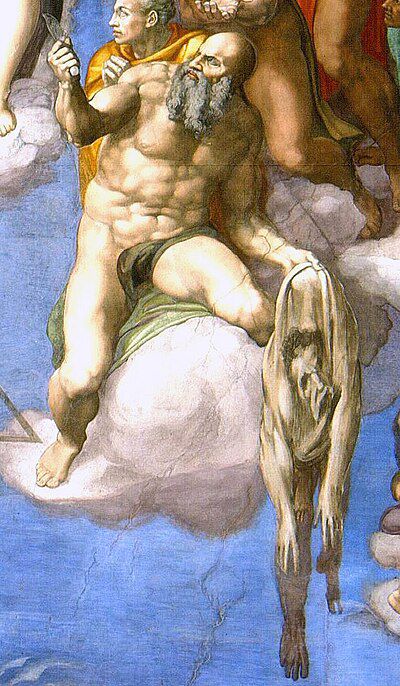

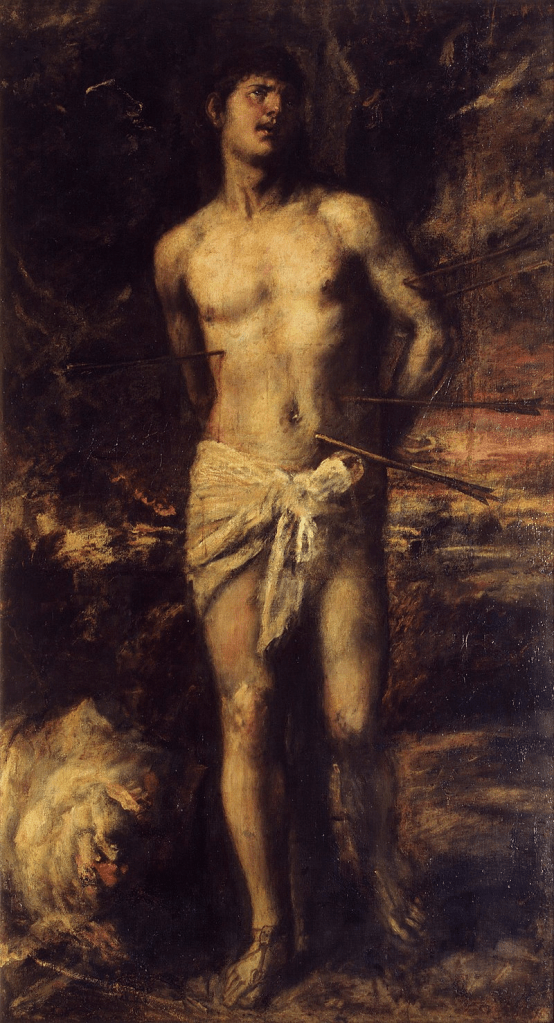

Certainly, Ricketts has a case in singling out Titian’s Saint Sebastian. There is defiance in the face of the Sebastian in it at the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune set against by the perpetrators of his attempt to make him a martyr. This body, in no way as sensual as Michelangelo’s men, is unlike some of those men, notably Saint Bartholomew, with whom Michelangelo so identified that in painting’ for The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, the hanging skin torn from that saint he created what people identify as his self- portrait as a man suffering for his demanding beliefs:

Titian’s Sebastian is no equivalent of this man, flayed in the name of his belief in order to witness the new Christ and slew off the old body of sinning man’ especially as Ricketts might have seen it the body of ‘sinning’ and suffering for it, the tortures a heteronormative and homophobic set of social norms reserve for queer men. Look at Titian’s Saint and we see Ricketts says:

There is something Latin in the fibre of Titian, in his sense of reality and sense of control. … he belongs to a patrician people to whom experience is met by the force equal to control it’.

Is this indeed what you see there as Titian does. The look of Titian’s Sebastian is certainly that of a man who understands that it is his lot to suffer, but to do so in a stoic manner befitting his dignity. This dignity is that of a man signed out to stand up in an August role, even to take it on by imposing on it the contrapposto pose of young male beauty adopted from Classical Greek statuary. This man is young in ways that strike us in the early maturity, only half-developed of the young lad’s body. Such dignity has it has that is patrician, notably in the Roman nose (‘something Latin in the fibre of Titian’), is that inherited from the finesse of a patrician genetics and schooling. In Rickett’s view the ‘sense of reality and sense of control’ of Titian and his figures (before the very late ones anyway) waas an inheritance of Roman virtue too that was tantamount to his identification with the Venetian nobility and its public face. Note this fine paragraph:

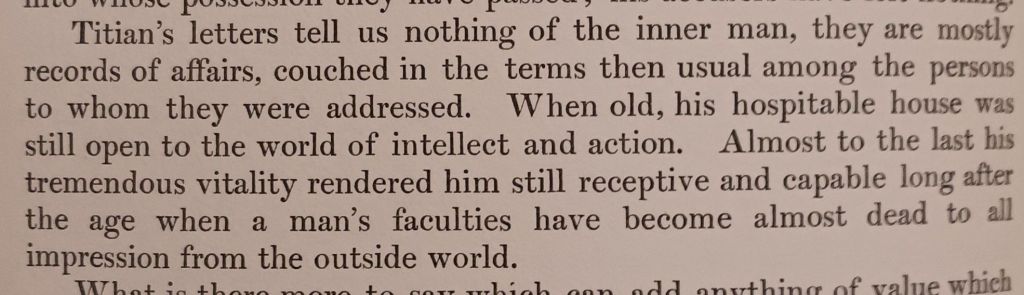

The ‘inner man’ is entirely absent from the record in Titian, he thinks, as was the case with the persona of the Roman patrician families. His tentacles of sense led only to the outward world, not to an inner one (or at least apparently so). His self was a public self, perfectly at ease being so, even as an artist he ‘translated into the terms of painting something characteristic of the race’ (he means Italians of course though only in the nineteenth century were Italians first thought of as a ‘race’) ‘to whom we owe the pattern of civility and the grammar of our arts’. [2] And more importantly the Titian (again before late Titian and the struggles of The Flaying of Marsyas) he valued that of a ‘power’ with ‘roots in the wealth of a nature outwardly placid, yet varied and strong with the strength of a perfect sanity and health ripened by the richness of the sun’. It is not only that Titian’s Saint Sebastian bears that same natural tan, the mark Ricketts thinks of the Italian race, but that he clearly thinks nought of the arrows fired upon him and the pain they could be thought to bring. If there is pain he will not show it. Even the intense background of Sebastian with its many inchoate features is to Ricketts, as in all Titian’s paintings, ‘ever varied and not deliberately abstract’, bringing in ‘ a new element to give ,magic, mystery, and concentration to the economy of his designs’. Ricketts meaning here is far from clear (for magic does not require clarity) but in my view, he is explaining why, for instance, Sebastian’s background could be a background of the sensuous inner .ife allowed top the patrician classes.

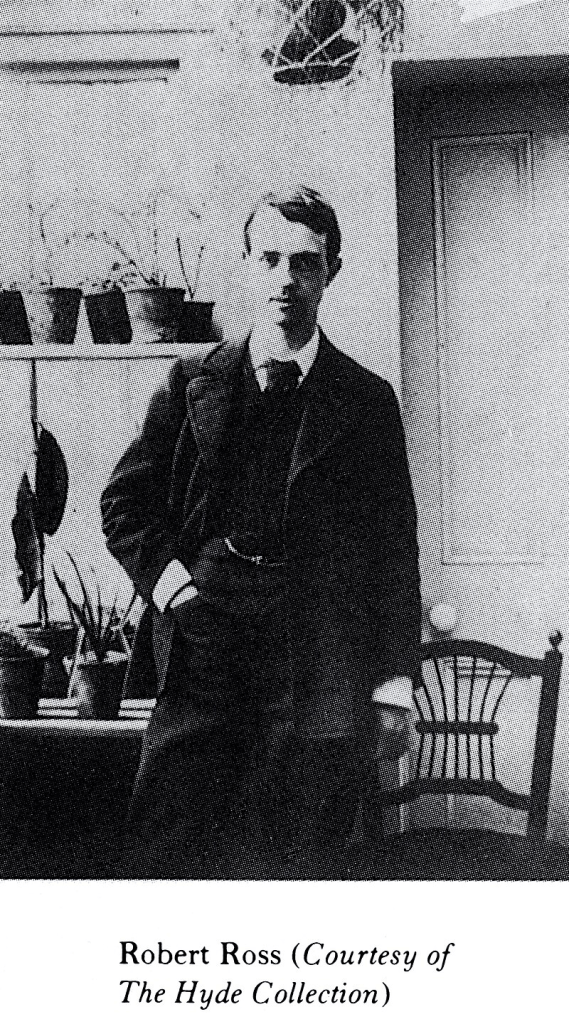

And let me say that I think this is because Titian revels in the homosomatic (again my term introduced earlier), a sense that lingers lovingly on the nude body of males without demand of it or responses to its stimuli. Of course there are excellent reasons why Ricketts might have sensed this quality himself. His aesthetic grasp of male beauty aligned with his sensual need of stimulation and response to that embodied beauty. His book on Titian is dedicated to Robert Ross, usually known as ‘Robbie’, that most loyal friend and interpreter of Oscar Wilde, and a man who knew better than most the issues caused to the nineteenth century patrician gentleman in London.

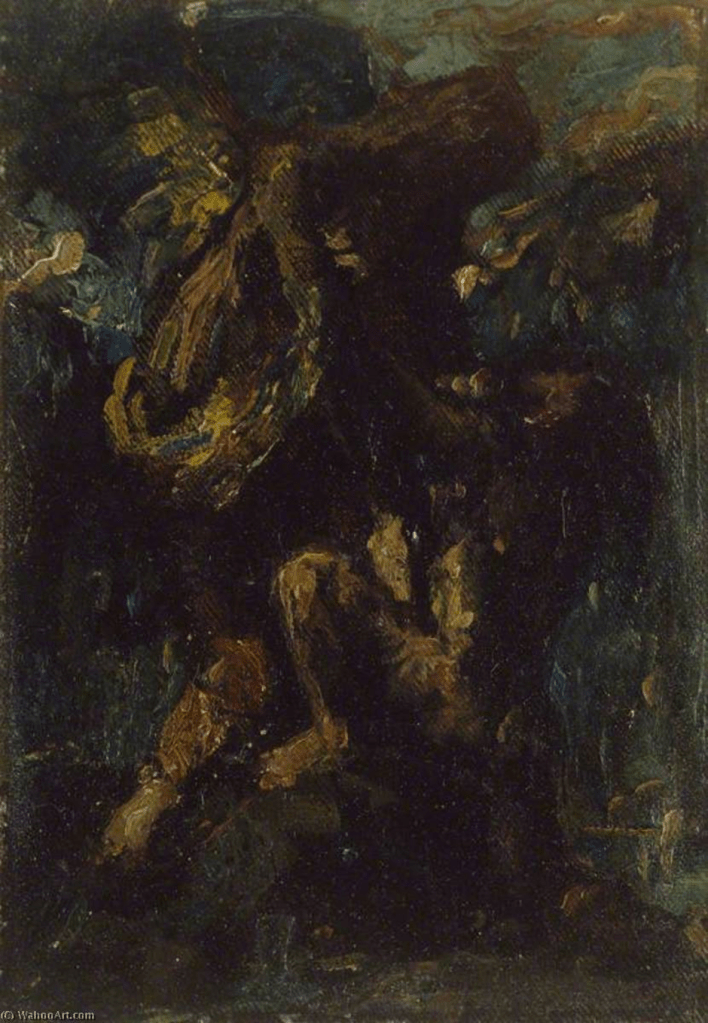

In my interpretation, solely as a queer man responding to the unsaid in another, Ricketts felt very much the awfulness and fear of being subject to the fate of Wilde though Wilde, he and Shannon ought to have every entitlement to patrician outer identity but for heteronormativity and homophobia which caused the appreciation of male beauty in him to be occluded. That occlusion, again in my private view, darkened the sensual beauty of the only partial view of the encounter of two semi-naked males, which is his Jacob Wrestling with the Angel.

There is glory and there is darkness therein – not only to throw queer-hunters off the scent, but because in his society angels brought skewed homophobic messages from a homophobic God. No homosomatism here, then! That Ricketts felt entitled to inherit the patrician view offered by the British Imperial scene at its height in his time otherwise for both himself and fellow artist and lover Shannon is I think conveyed by his admiration of Whistler for in ‘his old age’ departing from ‘a respectful hostility’ (to Titian) to rank L’Homme au Gant above the slighter paintings of Velasquez’, despite, and possibly because of ‘angry treble’ against it from Ruskin (the ‘cry from the pelican in the wilderness of Victorian England’ says Ricketts).[3] That latter mentioned painting however is the partrician and homosomatic ideal itself of Titian however soberly clothed it be.

That pointing finger is replete with unspoken and uninterpretable meaning which possibly has some relation to Titian’s knowledge of the arcane and occult, but that young man’s olive skin, shown by the plunge in his neckline, is surely the kind of public embrace of the sun and outer man that Titian valued in his young male aristocratic models, whoever they may have been. This man of open gaze stands as an emblem of male beauty fulfilled in a public role of an who is also inheriting the riches of his past , like those beautifully crafted gloves – the whole focus of the portrait, from which he has withdrawn his beautiful hand.

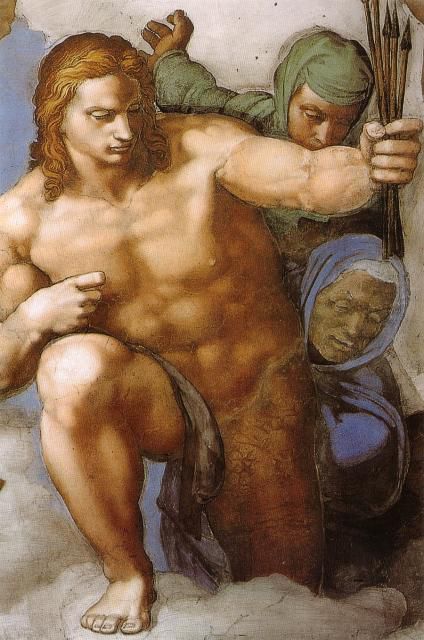

But if Ricketts is right about this reading of Titian, he is possibly wrong about Michelangelo – at least in his ‘conclusion’ to this book. That is because Michelangelo giants, even when the tradition of their interpretation lent itself to the homoerotic, are not at ;’self-questioning’ and twisted by the effort of staying straight. Since Ricketts instances Titian’s Saint Sebastian against Michelangelo, looking at the same saint in the Sistine Chapel The Last Judgement by Michelangelo does not fit Ricketts’ description . Here the youthful giant, beautiful ans sensually appealing in his butch young beauty in every way, has taken the arrows of homophobia and heteronormativity from his body. in preparation to join the Saints and the Elect at this moment of exoneration, with Saint Catherine, and (his genitals covered by accident it seems, is offering his beauty up to the public gaze. This Saint Sebastian is not patrician. He is built by muscular effort and he cares not a jot that some see his naked beauty as evil, for he knows it is not.

On the whole, I like the classless beauty of this rather more than the class-bound early Titian picked out by Ricketts. Of course, bourgeois gentlemen had every right to be disgruntled at being singled out from their class entitlement, but Michelangelo does not go there – however tortured religion latterly left him (see the blog, at this link, on the last British Museum exhibition).

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

___________________________________________________

[1] Charles Ricketts (1910: 171f.) Titian London, Methuen & Co. Ltd.

[2] ibid: 172

[3] ibid: 171