The choice of vocabulary to describe the world we are always trying to shape around us and our needs – either in societies, groups or as individuals – is sometimes the most urgent issue in those worlds. This may be because our chief business as meaning-makers and users of meaning is to get things done (as we see it) or to ensure certain fundamental things are not done like implementing real change where it is most needed. Avoidance is often the reality behind our perception of a world that just is rather than of one that can be changed for the better.

However, the strange and archaic vocabulary choices in my title are not what I am addressing here by focusing on choices of vocabulary. The choice of words in my title – legitimate ones but vanishingly rare in modern usage – is not how we shape worlds. The words in my title I expect that we might all look up are ‘fictile’ and ‘fingent’, although we might be advised to also look up, which we might not unrequested, is the meaning and origins of the word ‘plastic’.

All of these words were somewhat archaic when used by the source I take them from: Thomas Carlyle’s History of the French Revolution. He uses them in describing the fragile situation of monarchy under the reign of the hugely weighty (if not in significance) monarch Louis XV in France, well before the Revolution in the reign of his son Louis (to become the XVI of that name). Here is the gorgeous and busy little passage (I will come back to why I emphasise the word ‘busy’ here):

For ours is a most fictile world; and man is the most fingent plastic of creatures. A world not fixable; not fathomable! An unfathomable Somewhat, which is Not we; which we can work with, and live amidst,—and model, miraculously in our miraculous Being, and name World.—But if the very Rocks and Rivers (as Metaphysic teaches) are, in strict language, made by those outward Senses of ours, how much more, by the Inward Sense, are all Phenomena of the spiritual kind: Dignities, Authorities, Holies, Unholies! Which inward sense, moreover is not permanent like the outward ones, but forever growing and changing.

Carlyle knew that his choice of Latinate words like ‘fictile’ and ‘fingent’, and, in his age, even ‘plastic’ were daring ones. Yet each of these three are used to emphasise by repetition of meaning and some aspects of their sound, a basic notion of the world as he wished to describe it, and not just in eighteenth-century France, as one shaped by human art and craft, even if unconsciously. See, for instance, how etymonline.com describes the etymology of the adjectival word ‘fictile’:

fictile (adj.) :1620s, “molded or formed by art,” from Latin fictilis “made of clay, earthen,” from fictio “a fashioning or feigning,” noun of action from past participle stem of fingere “to shape, form, devise, feign,” originally “to knead, form out of clay” (from PIE root *dheigh- “to form, build”). From 1670s as “capable of being molded.” From 1854 as “pertaining to pottery.” Related: Fictility.

In reading that, note that the word not only has a relationship of sound to the word ‘fingent’ (fingere) but also one of meaning. Note too that this word does not occur in etymonline.com and that the Oxford English Dictionary has only ONE example as the earliest of its meaning – this very one in Thomas Carlyle, though Mirriam-Websters cites a more modern usage (obviously owing a lot to Carlyle) as meaning ‘ pliable, flexible, yielding‘. The point is, as Carlyle busily labours it, that what we know as facts in the world are shaped and re-shapable fictions, more fluid and more re-shapable in form (and perhaps function) than we like to think, and perhaps, in our common usage of the term ‘real’, less real than we like to think.

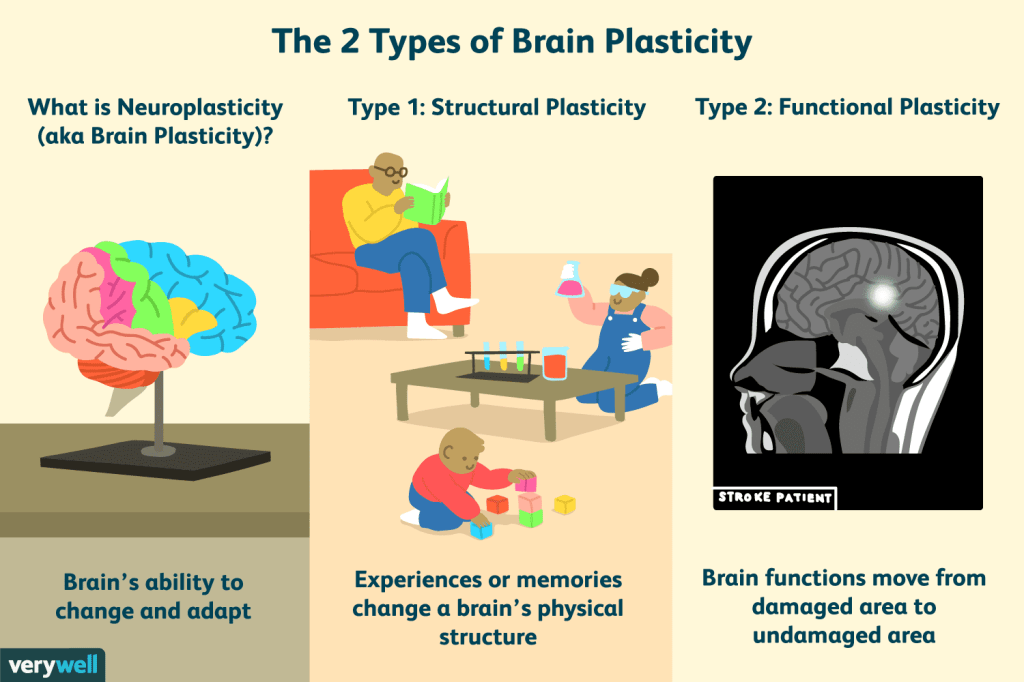

The point is that both as mental and physical objects, Carlyle sees the stuff we think of as real and factual as, in fact, constructed. To some extent, and more obviously to us as the climate and environment become more obviously the things of common human shaping (and not for their betterment moreover), we can see those physical things as an accident of human economic ‘busy-ness’ and of manufacture and distribution. And we construct them, it seems, in ways that make them an apparently destructive force. Real objects in the world like the weather or topographical structure of the world’s surface are things humans keep remaking without sometimes knowing they are doing so. And so much more so is that the case for human institutions and internal human belief structures on which governance, social beliefs, and ethical and religious ‘truths’ depend. This is even more the case with the word ‘plastic‘, now used more often in relation to the concept of ‘neuroplasticity‘: the function of reconfiguration of supposed realities in the central nervous system itself.

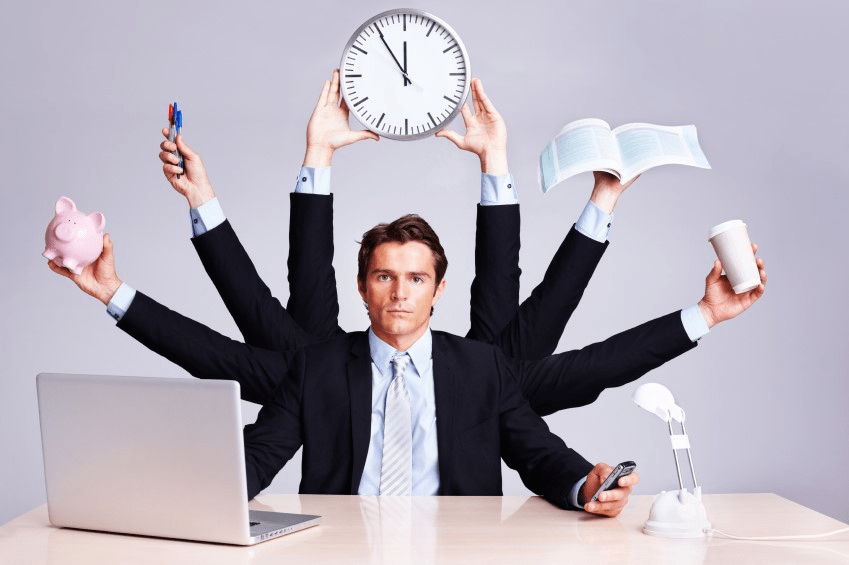

Rather we shape our ‘fictile worlds’ through the use of words to which we think we know our full intended meaning in using them but do not do so. The key word in my title then in this respect is not ‘fingent’ the word ‘business’. When it is used in the prompt question we are all meant to know what it means – it is an activity aimed at the making of commodities (products or services) that can be made and distributed to end-users more cheaply than than they can be costed for sale in order to make a profit. If we go by the Wikipedia entry for the term, and even perhaps its supposed ‘disambiguation’ as a term, that is all we can mean by it except in extreme anomalies, such as that in which it means defecation, or one I do find interesting . But the idea of business has a lively meaning in everyday talk where it has none of those meanings – or at nearest only one as described in the disambiguation as a collection of ferrets, For the swirling activity of ferrets might be just what we mean by business or ‘being busy‘ usually in our talk. Our conviction that we are ‘busy’ and cannot help but be forced to be busy is often our excuse in human terms for not acting where we know action is required – in order to change, for instance, the very motive forces that keep us busy, often unnecessarily except to avoid some other demand upon us.

This usage of the term is not unlike the way in which we resist intrusion into our lives, especially those parts we wish to keep only under our control, when we tell people that their interest in us is over-intrusive: we can often frustratedly say to others that what is happening to us is ‘none of your business’, for only the collection of ferrets in us know why they are in such apparently nonsensical over-activity. This use of the word ‘being busy’ to deflect from others scrutinising ones ‘business,’ and advising change was recognised as a social defense mechanism by Isabel Menzies-Lyth in her now neglected classic study of hospital nursing in 1960, ‘A case-study in the functioning of social systems as a defence against anxiety. A report on a study of the nursing service of a general hospital’ (published generally in Menzies Lyth, I. (1988) Containing Anxiety in Institutions, Vol. 1. London: Free Association Books) .

The work of Isabel Menzies-Lyth is becoming forgotten (because we are too busy ‘getting it done’ (whatever harmful thing we are doing – like Brexit for Boris Johnson, who was a very ‘busy-in-the-purpose- of being-a-neglectful’ soul at least in his public face – as I have already suggested, together with that of her chief mentor, Wilfred Bion, who gave new impetus to the study of group psychology in the ‘object-relations’ or Kleinian school of psyschodynamic psychology. Lytham showed that in hospitals, change is near impossible to implement for a number of reasons (relating to how professions guard themselves from change or even scrutiny), listed thus in a blog by Dr David Lawlor in 2016:

The main message of her paper is the elaboration of how these defensive techniques are played out in the organisation of the nursing service. They are:

- Splitting up the nurse-patient relationship

- Depersonalisation, categorisation, and denial of the significance of the individual

- Detachment and denial of feelings

- The attempt to eliminate decisions by ritual task-performance

- Reducing the weight of responsibility in decision-making by checks and counter checks

- Collusive social redistribution of responsibility and irresponsibility

- Purposeful obscurity in the formal distribution of responsibility

- The reduction of the impact of responsibility by delegation to superiors

- Idealisation and underestimation of personal development possibilities

- Avoidance of change

Her conclusions give a powerful picture of dynamic processes at work within an institutionally defensive system.

These are powerful process, each requiring explication (if you do not want to read the essay yourself or are too ‘busy’ to do so), but they are intimately related. She deals directly with nurse ‘busy-ness’ as a defence in terms of a number of them, including ‘the splitting of nurse and patient relationship’ from a human to a ‘business’ relationship, but centrally under the heading of eliminating ‘decisions by ritual task-performance’. However, remember that, in fact, all 10 of these techniques tend to get co-involved and that they don’t describe what happens to nurses per se, but to all corporate structures in which task and process trumps reflection,reflexiveness, and disruptive revision of practice as a norm.

Yet, I once had the unhappy experience of teaching safeguarding to nurses in TEWV (Tees, Esk and Wear Valley Mental Health Trust) for Teesside University, where I found a senior nurse complaining in class that her and her ‘team’s’ responsibility was entirely that prescribed in hospital policy documents and operated and supervised by extant managerial processes not in her and her ‘team’ taking personal responsibility for young people themselves, however urgent the issues individual young people presented. That same trust was later found to have deficient practices leading to a number of deaths of young mentally ill persons in its care. This was and example where the course, meant to be a ‘personal development possibility’ which clarified personal responsibility in safeguarding, particularly of the young mentally ill people who died whilst in the ‘care’ of TEWV as an institution. That no-one noticed the need to change still puzzles that Trust, still pushing out policy documents that it is no way the responsibility, except as an idea in the mind, for individual practitioners to own. The academic university, often called a ‘zombie institution’ by ‘creative disrupters’ is another fine example of such institutions where I have perceived the same practices as in health, social care and other

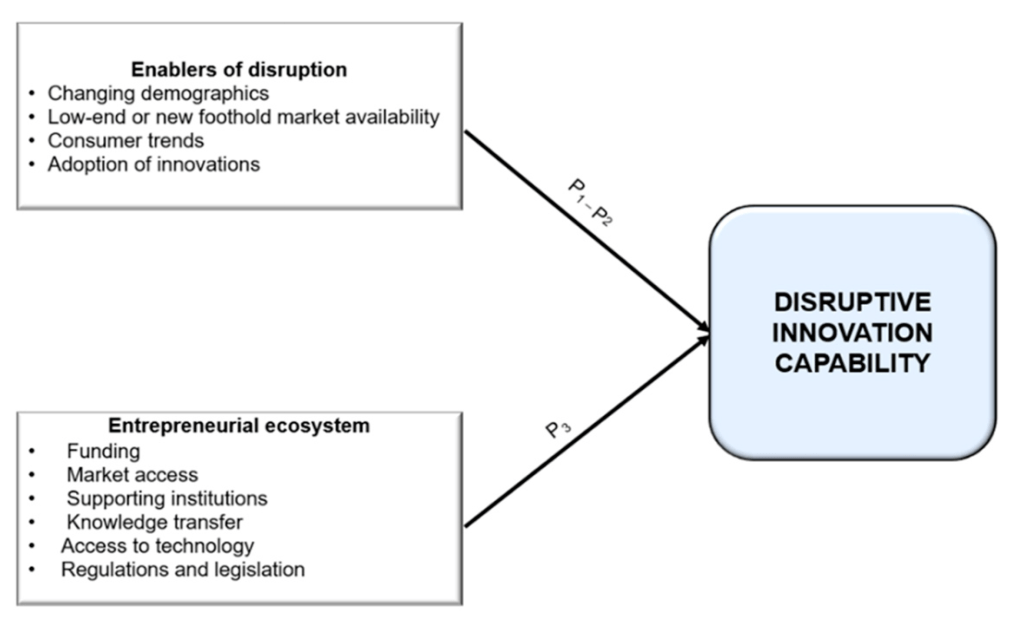

And yet busy-ness remains the self-perception of the day of workers in such institutions and their business (remember no-one can intervene for it is ‘not your business’) is the maintenance of the status quo not the care of patients or other ‘end-user’ of the business’s services and / or products. Of course, I know that good business schools actually teach the need for disruptive innovation in business (especially corporate businesses relatively closed to external competition). Harvard Business School claims that it has been promoting this model for 20 years at least. Schumpeter actually called those practices ‘creative destruction’. Here is an example of the kind of graphics these ideas have evolved:

Enablement of disruption is, of course dependent on forces of change (call them P1)being greater than forces of stasis (call them P2) and on P3 being a positive not negative force, saince it could be entirely negative.

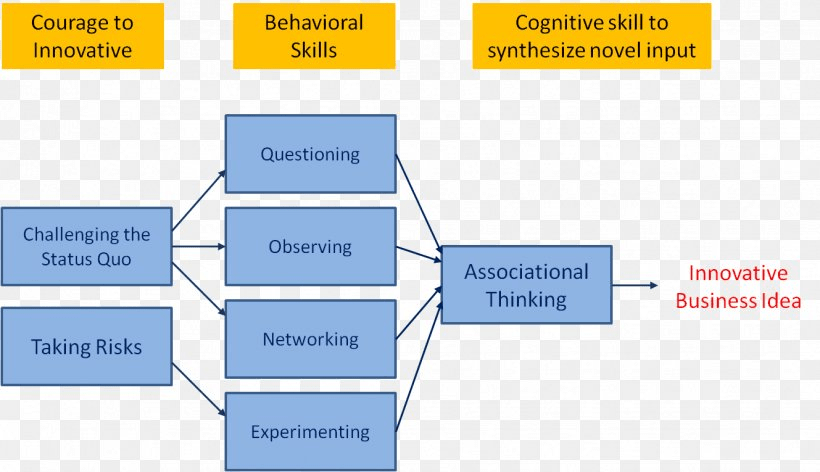

In such disruptive innovation, disruption is necessary to establish the importance of the primary guiding rule and end-satisfaction of end-users rather intermediary users (those often who work within the business) – learners not teachers, patients not health workers and service-or-product-users of all other kinds. The practices are associated wih definable skills, as in the following infographic:

And still we keep the status-quo spinning in its own interests in huge supposedly public service institutions like health and education arenas, regardless of whether they are driven by private or public enterprise initiatives. And that, I think is because, the forces of regulation – you can see it in four search disruptive or challenging behaviour on the internet is mainly about how institutions (though their Human Resources departments normally) view disruptive behaviours (or a version of it in mental health or learning difficulties we call challenging behaviours) as negative forces, whether their effect is negative or not. In the latter cases the practices that are being challenged by challenging behaviours most often need challenging and disrupting. Even when treated empathetically, such behaviours are seen as unwanted challenges to societal norms.

But if worlds are fictile, they only change when they are challenged, and this is what Carlyle saw in the Fall of the Bastille in the french Revolution – the false of a charade representing a status-quo that had no support in human hearts, minds and in progressive human behaviour. Even more important was, he thought the drawing up of a constitution on the principle of the rights of the many – a phenomenon he called Sans-Cullotism (cullottes being only worn by the bourgeois and aristocratic gentleman). Here is more stirring Prose:

“The ‘destructive wrath’ of Sansculottism: this is what we speak, having unhappily no voice for singing. Surely a great Phenomenon: nay it is a transcendental one, overstepping all rules and experience; the crowning Phenomenon of our Modern Time. For here again, most unexpectedly, comes antique Fanaticism in new and newest vesture; miraculous, as all Fanaticism is. Call it the Fanaticism of ‘making away with formulas, de humer les formulas.‘ The world of formulas, the formed regulated world, which all habitable world is,—must needs hate such Fanaticism like death; and be at deadly variance with it. The world of formulas must conquer it; or failing that, must die execrating it, anathematising it;—can nevertheless in nowise prevent its being and its having been. The Anathemas are there, and the miraculous Thing is there. Whence it cometh? Whither it goeth? These are questions! When the age of Miracles lay faded into the distance as an incredible tradition, and even the age of Conventionalities was now old; and Man’s Existence had for long generations rested on mere formulas which were grown hollow by course of time; and it seemed as if no Reality any longer existed but only Phantasms of realities, and God’s Universe were the work of the Tailor and Upholsterer mainly, and men were buckram masks that went about becking and grimacing there,—on a sudden, the Earth yawns asunder, and amid Tartarean smoke, and glare of fierce brightness, rises SANSCULOTTISM, many-headed, fire-breathing, and asks: What think ye of me? Well may the buckram masks start together, terror-struck; ‘into expressive well-concerted groups!’ It is indeed, Friends, a most singular, most fatal thing. Let whosoever is but buckram and a phantasm look to it: ill verily may it fare with him; here methinks he cannot much longer be. Wo also to many a one who is not wholly buckram, but partially real and human! The age of Miracles has come back! ‘Behold the World-Phoenix, in fire-consummation and fire-creation; wide are her fanning wings; loud is her death-melody, of battle-thunders and falling towns; skyward lashes the funeral flame, enveloping all things: it is the Death-Birth of a World!’ Whereby, however, as we often say, shall one unspeakable blessing seem attainable. This, namely: that Man and his Life rest no more on hollowness and a Lie, but on solidity and some kind of Truth.”

So for my ‘crazy business idea’, lets understand that all ‘business ideas’ are a kind of craziness – an attempt to raise need and want on the basis of a presumption about the world (presumptions, pretensions or unsupported ‘formulas’.

Instead lets do away with business (and busy-ness) and promote the idea of well-being that is not a lie but a truth – in as far as this is possible- that satisfies every ‘end-user’ in and of Life. Clean air might not be seewn as a by-product of wealth but as a means of promoting regulated well-being. Regulation is not a formula. Healthy regulation is a means of living within and not beyond the needs of life, and certainly not for the purpose of busy-ness nor ‘business’. And this depends on radical change in the purposes of life. No longer are we ‘too busy’ to take notice of the wrongs of the world or prioritise something other than a dehumanized notion of ‘work’ or other hollow goals. The hollowness lies in seeking apparent rather real satisfaction, for selfish interest not general well-being, for the foolish mask of money interests rather than life-interests.

Is it a ‘crazy business’ idea to promote action only that sustains more life and less its pretensions? I think not.

Happy New Year

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx