Geoff and I are confined these days following Geoff’s serious illness, and we don’t think we can visit the great art exhibitions, theatre, or even cinema in the cities we would take pains to go to: Edinburgh, London, Manchester, Liverpool, or even the nearest of the great cities, Newcastle-upon-Tyne. Macbeth knowing that his agents have failed to murder one of the men who appear to him to threaten, being alive, his right to a dynastic throne, feels ‘cabin’d, cribb’d, confin’d’ instead of being ‘broad and general as the ‘casing air’ (Macbeth, Act 3, Scene 4) – a case that is too open and transparent to encase you entirely.

Prophetic souls oft jump to conclusions about their general situation, as does Macbeth, but Geoff and I notice daily how much we are increasingly helpless, as your opportunities to see others drops away as the once pleasures seem to have necessarily become duties. It is the way of the world, no doubt – but the truth is you have to make an effort to get out and see someone and something. Yet if your jaunts are just local, are you not as ‘cabin’d, cribb’d, confin’d’ like Macbeth in your purpose? Hamlet felt the whole of the country of Denmark was too local for him when it triggered dreams, making it clear that we make our circumstances to be what they are merely by our interpretation of them (Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2):

Hamlet: To me [Denmark] is a prison.

Rosencrantz: Why then your ambition makes it one. 'Tis too narrow

for your mind.

Hamlet: O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell, and count myself a

king of infinite space—were it not that I have bad dreams.

There is our dilemma. Is being confined to local events a ‘prison’ or is it merely that we let ‘bad dreams’ get in the way of enjoying the local? Are we, like Macbeth, failing to enjoy our present, fearing for the future of his royal line instead in bad dreams? Are we locked into our circumstances, or can we ‘count ourselves the king of infinite space’ just by thinking it is so? Geoff’s mobility is limited by his lung condition, and we don’t know how much recovery he will make (but can and do hope) or how long such recovery will take. The house is a mess as I struggle to maintain things, but not as we had them, and we need to get out (with wheelchair in boot for Geoff that was gifted by a dear friend, Joanne) and the old ailing car stuffed with aids. Geoff gets tired and breathless, and clearly, we can’t go that far. Even a trip to the nearest town to Crook, Bishop Auckland, is exhausting for him. Yet we do it – we explore our nutshell, hoping to find more space in it that had seemed its constricted casing.

Suddenly confined to the local, we eke out what we might see, that does not involve travelling in lifts, for to Geoff these are a no-no. We went for a coffee in Bishop Auckland Town Hall (BATH) and found the exhibition of local art and artists in progress. We went around but hadn’t the energy to do the usual scrutiny of the names of artists. Hence, this is just a summary of what we took from the idea of what it means to exhibit the local locally. Local art is perhaps art ‘in a nutshell’, lacking the generous validation surrounding great collections – even in Bishop Auckland, where the major gallery is one of seventeenth-century Spanish art mainly. If local art is to satisfy our inner wanderlust then the ‘local’ ought to mean more than the aggregation of art by individuals living in a particular locale. An organisation dedicated to ‘Cultural Place-Making‘ exists and its website emphasises the art of a locale is in fact part of a conscious and unconscious collaboration to ‘make’ a specific sense of the ‘local’ meaningful. Here are some definitions from that website:

The Arts of the Local Culture are those artistic activities and works dedicated to the service of the local culture. The arts of the local culture are rooted in the civic resources and values of a given city or region. These resources include regional history, local demographics, creative businesses, and the resident arts community. The arts of the local culture are engaged in the work of civilization in the community.

Local Culture: Small cities, towns and urban boroughs naturally produce a local culture. Most local cultures are somehow unique, the product of their specific history, demographics, creative entities and the infinite variability of their inhabitants. A healthy local culture produces an integrated network of organizations, businesses, civic institutions and individual participants who generally share a pattern of beliefs, values, and cultural objectives.The Best Practices in Cultural Placemaking section of this website seeks to identify many of the essential characteristics of a vigorous local culture.

Does this input help us to see the impact of a local exhibition? If you wanted to test this, you might deliberately ignore the personal in the production of local art – even neglect to discuss it through named creators as the cultural product of bourgeois culture that harmonised cultural production under the fragmenting ideology of individual copyright. But, of course, that wasn’t the reason we neglected to take the names of artists. That was purely pragmatic and situated. Yet some of the art here not only feels to capture the local but to capture through the subjective features of its topic.

Take the images below, which have increasingly grown on me and made me want to seek information about the artist and their intention. It features a partial figure in each image – perhaps a self-portrait of the artist or perhaps a figure in their life. I just don’t know. What is clear is that the figure takes colour and tone from its location and that factors, including costumers, also change the meaning of the figure. I dream that this is in itself a paradigm of the local – the person is both the same in each locale and is not – details differ and render the emotion conveyed different – from what seems a wooded hill, to a background of plain and hills (distance and hence perspective unknown) and then beach and dunes in the third. These scenes feel North Eastern and I sense the figure in landscape plays variations on the themes of the local, deepening and widening its meanings and their contexts. In a sense, it is a piece that finds ‘infinite space’ in a constraining nutselll – or the casework of a painted frame.

There is no evidence for my reading – it emerges. merely from trying to see the ‘local’ as something more than the residence of the artists. Of course, sometimes the tieing together of location and the local theme is obvious. Paintings of place often pick out hackneyed places, rendering them with pleasing likeness but not much sense of a more expansive meaning. Thus the scene from the Castle mound at Barnard Castle of the old bridge over the narrowing Tees river at that point. Setting it in winter perhaps even more stereotypes it, though it makes fer fascinating shapes on the water caught between freeze and fluid.

Durham makes for lovely scenes but I prefer them like the top two below which use colour in oils and water respectively to queer the familiar:

The drawing of Framwellgate Bridge is a hackneyed subject but beautifully done – its problem being, I think, over-precision. Hence, I preferred the night scene below, I think of the same bridge but taking liberties with proportion and emphasizing emotion and power in its dynamic.

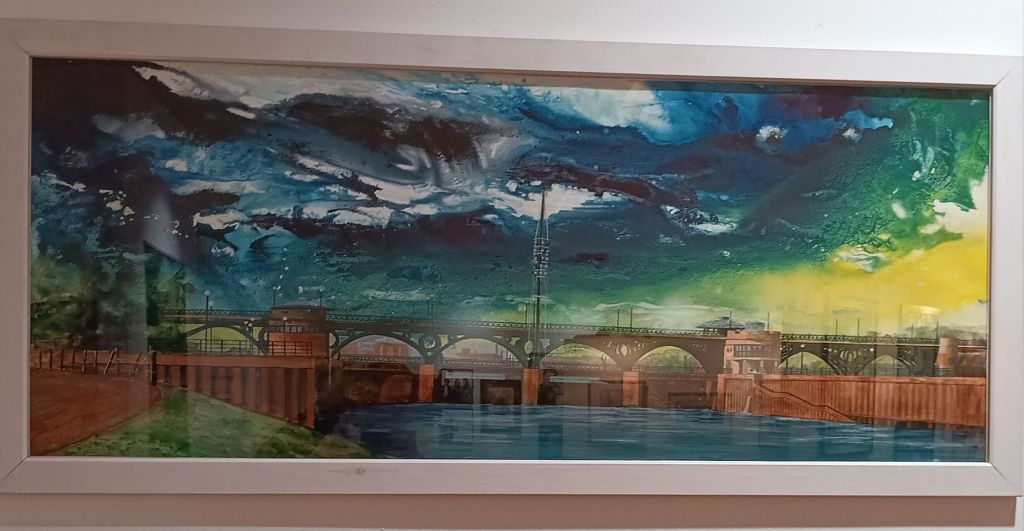

Likewise this interpretation of the Tees Barrage between Stockton and Middlesbrough. The sky dramatises a scene and renders it magically unstable, despite the brace defence put up by the Barrage. It feels to me like the place.

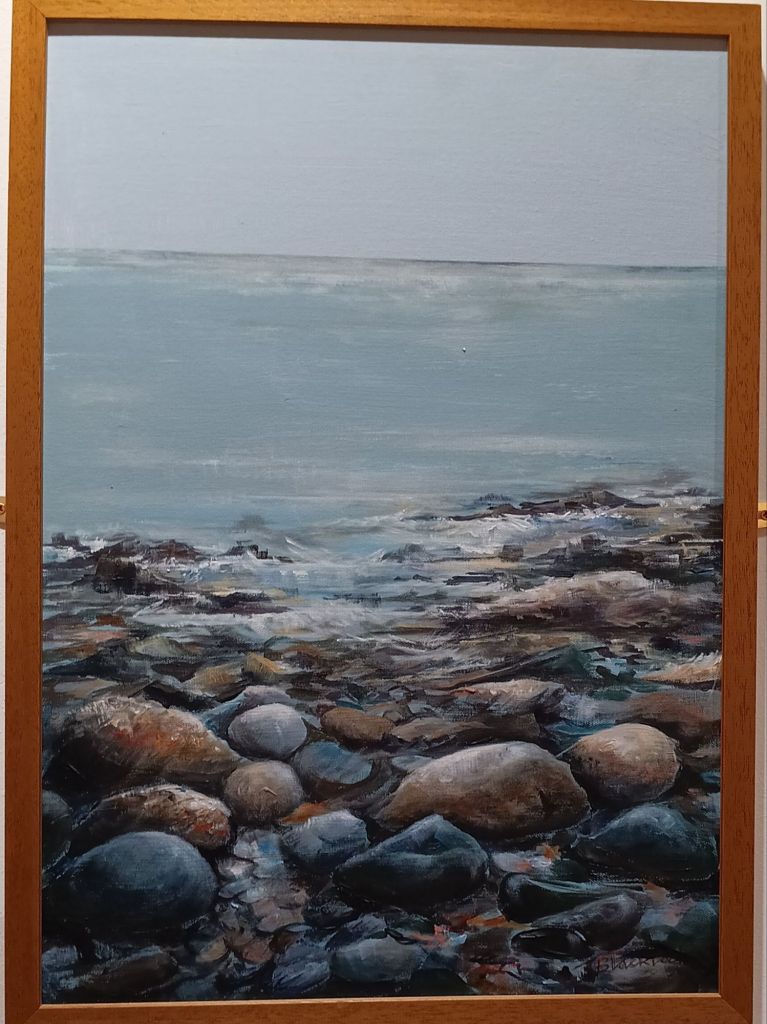

This estranged quality can even better indicate the way the real to can be specified by estrangements caused by human manipulation. I think of the chemical coloring’s of the stone on the beaches from Blackhall Colliery to Seaham and the strangely beautiful effect of these toxin-changed places from years of sea coal-mining and coastal dumping of on its refuse and its manipulation of the natural. But a good painting, such as that below of The Blast at Seaham, makes nature and colour manipulation indistinguishable. The choice of a low viewpoint, even further estranging by art a space that already hovers between nature and artifice by bringing in this third factor – conscious artistic manipulation.

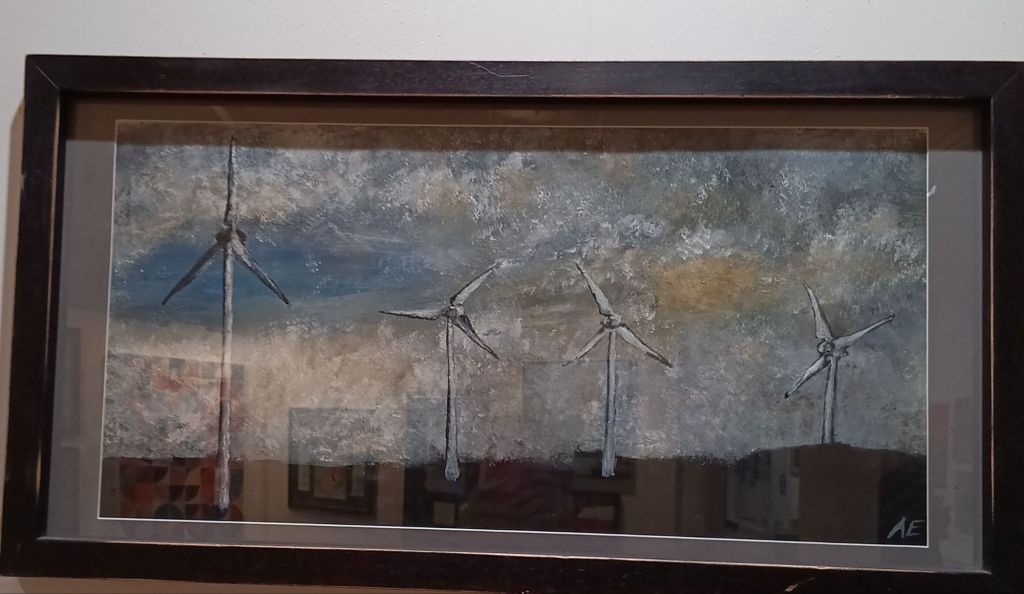

Something similar happens with pictures of modern Durham moorland wind-farms (below).

It may happen with the bridges over the Tees in Stockton, suddenly blasted into surreal colours. This isn’t about choice of colour entirely but at imagination of the meaning of the local location – for look at how choice of colours fails to make Dunstanburgh Castle look interesting. We would soon turn back to Turner from this.

And ideas alone don’t make art. Look for instance at the miner sculpted in coal below and set in an early domestic fire-hearth but framed in a modern fire heath surround. The contradictions glare – as does the burning scene behind the coal-miner in coal, but the idea feels too hackneyed. It isn’t an idea that works and aesthetically it displeases because too slick and polished. It speaks too much of the hubris of the idea – not enough of the real environmental, social and individual cost of coal-ming in Durham.

Nevertheless there are inventive landscapes here – in oils, water and photograph. The whole inset wall of them below can be unpicked to tell stories of the local, precisely because they avoid the prettifying of the natural that amateur landscape can often be.

Note these examples – good enough pieces but their meanings are neither local nor generalised – merely stereotyped. And that, despite the fact I recognise some of these scenes. They are estranged though not by art that makes us see but stereotypy that sees only what a an differentiating gaze refusing the challenging of art to render things into meanings rather than first impressions.

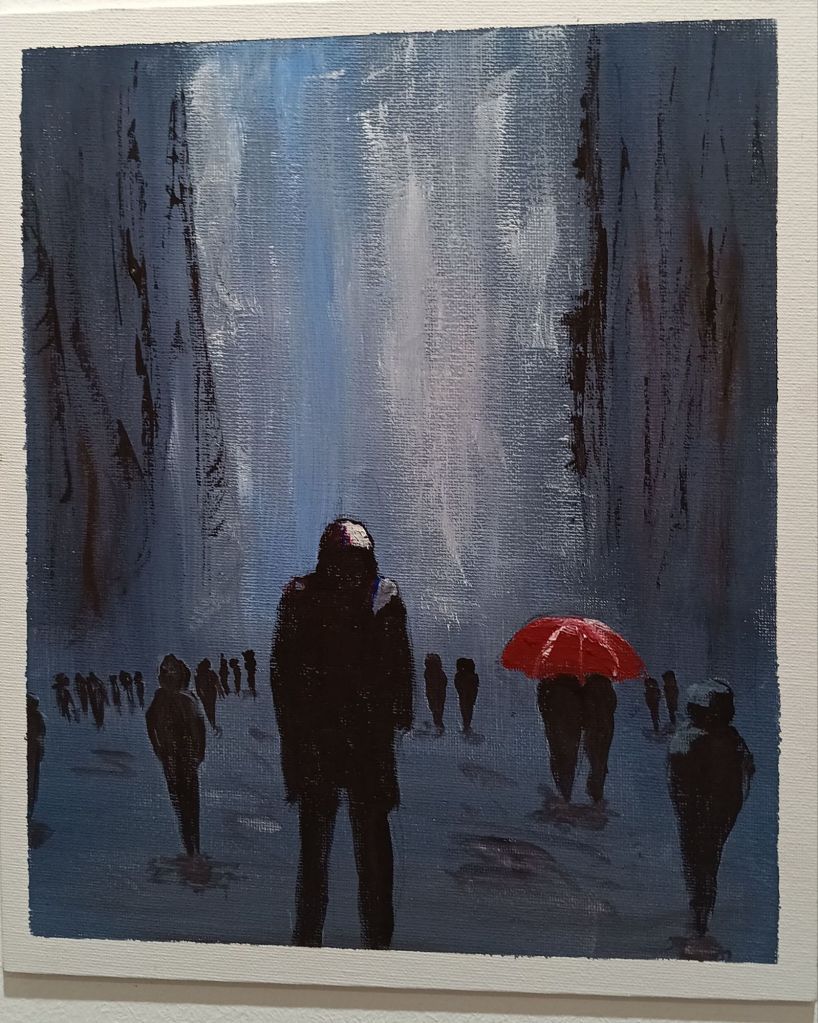

My favourite figures in landscape – if urban landscape – is totally unrecognizable as a local place but gives the local intense meaning. The setting could be entirely imaginary and tends to the apocalyptic – the shop fronts feeling somewhat like cliff-faces to a deep channel in a dream place. The figures are sometimes just markings of paint, the effect created by clusters of them in what could be empty space, even a vertical void that might swallow up the persons. Only one figure faces us but its face is lost in the shadow of its hood. This is a frightening place I know – it is modern urban northern existence. It is bleak. The shadows cast by figures seem like puddles of rain -the one couple in it – under one red umbrella – make one solitary shadow not two. But the colour and design are beautiful.

The nearest thing too it is also a rain scene – a photograph rather badly named Bollards on the March. Had we not known these were bollards we might have sense the same figurative anomie of these strikingly ‘human’seeming’ elements in a mysterious setting, seen through an even more mysterious medium – a rain-soaked window during falling rain perhaps. It is a beautifully eerie piece.

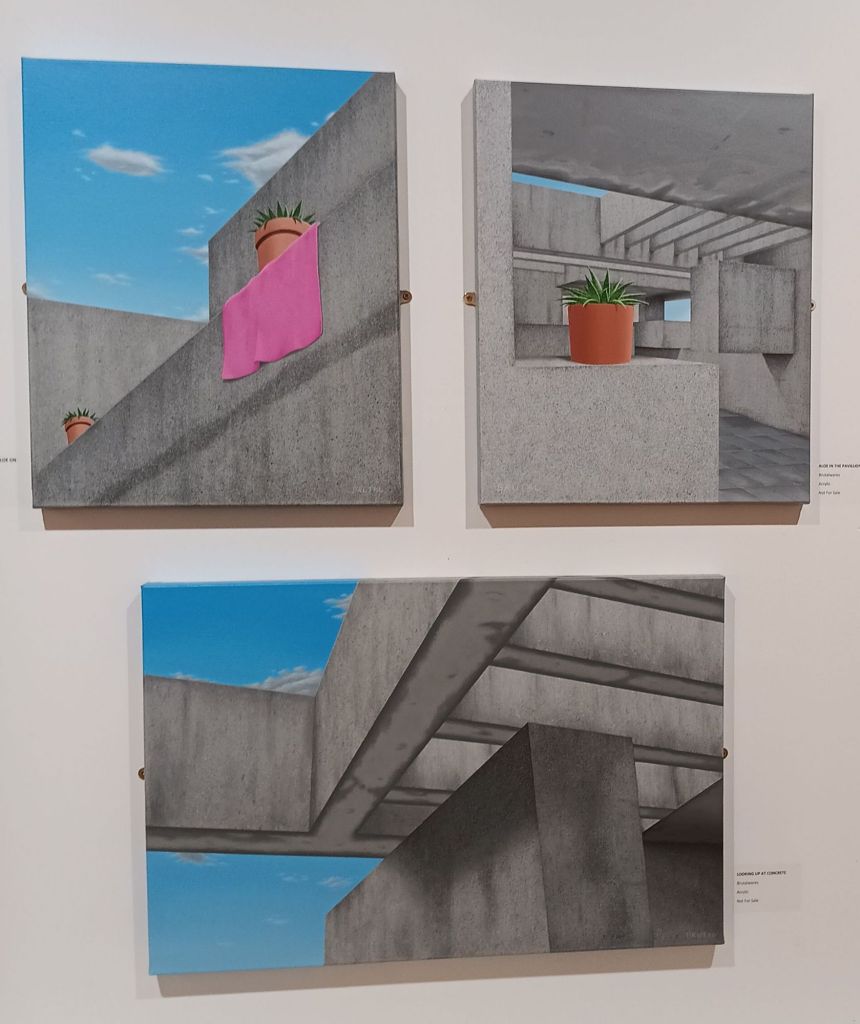

The evocation of figures in a landscape might be the essence of Northern art even when, as above, there are no ‘real’ figures. This is what our first picture did. It created a persona we yearn to see as ‘local’ but of diverse and variable meanings. Sometimes figures speak in their absence as in a seines of pictures of Norther brutalist concrete landscapes in which people are there only in the absence of selves – marked by things they have left behind. They are as real though as the characteristic stains in the reinforced material

Wen it comes to local people, the pieces are non-committal. many portraits are still playing games with famous faces, as in the undistinguished but lifelike Judi Dench in the set below, but this is an interesting wall (note it contains my favourite discussed above):

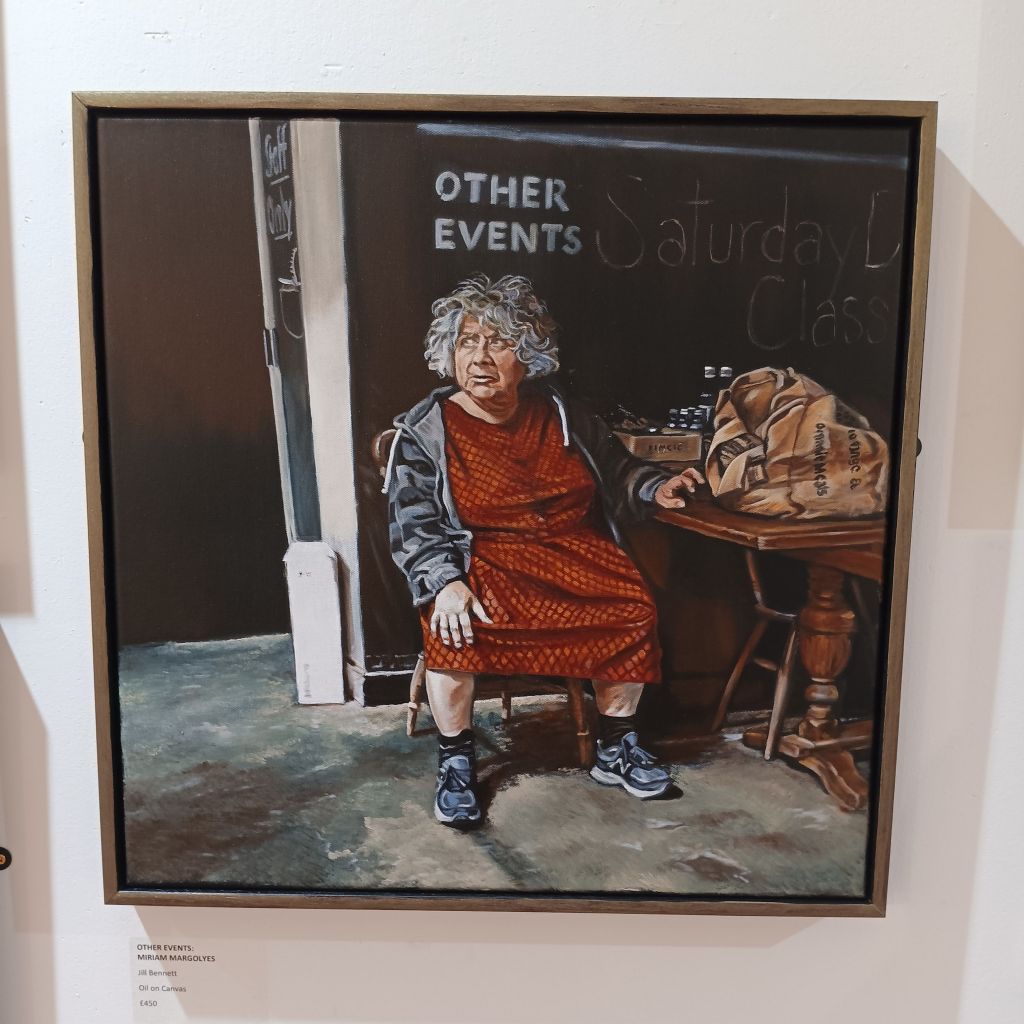

But locality is sometimes a matter of performative attitude. Miriam Margoyles, a comedy actor and much more was born In Oxford but has few links to Northern England, though she has to Scotland. But I sensed the portrait of her to be one of the most fine expressions of northern character, looking to its own tendencty to stereotype, even self-stereotype. I do not know if I can even justify that comment however.

Some pieces seem determined to find ways of addressing the exclusivity of northern stereotypes of exclusively white, working-class and midle-aged. One below does so by method – the male bust figure is made up of trade painter’s colour cards as a collage but of a man of mixed race, the second makes mixed-racial features an aspect of its beauty and appeal.

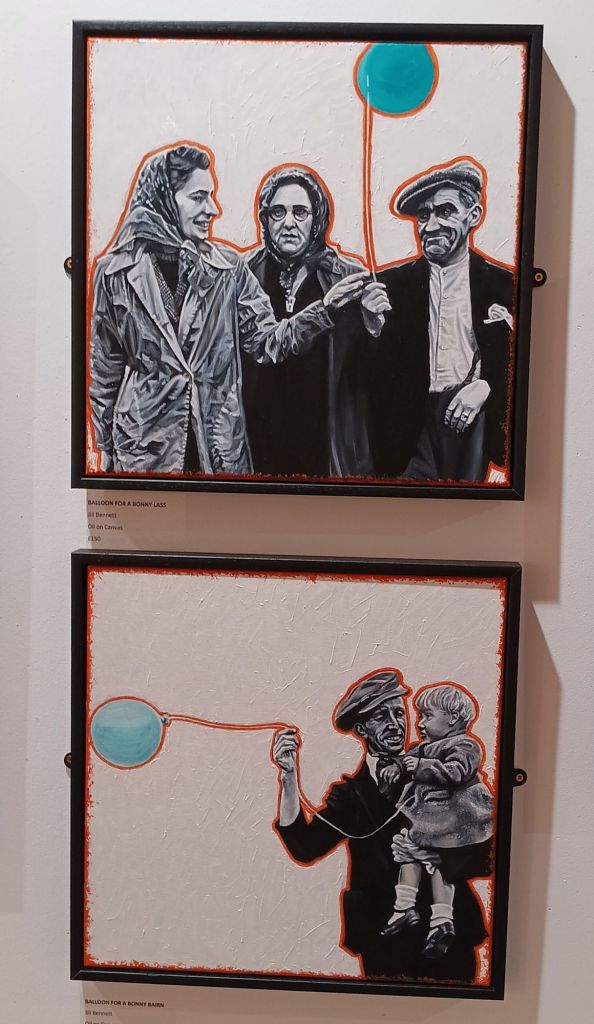

Where Northern sterotypes are used they were beautifully queered – by the simple device of adding an iconic balloon shape with string to the picture (see below). Though the lower picture fails to break the stereotype, which includes more than enough Grandads, the first does, rendering comment on sex/gender in a delightful way. It does in a manner not unlike the cartoon Blackpool postcard, but it raised a laugh from me.

But, in the end Northern scenes work best when they exude polysemous meaning from the gap in culture the North is often accused of, and sometimes praised for, being. note the below. I love them

Geoff and I returned from Bishop Auckland, a fifteen-minute drive but for the procedure with wheelchairs, feeling we had had a good day out. And suddenly the ‘local’ no longer see a ‘nutshell’, that is, of its nature, ‘cabin’d, cribb’d. confin’d’. In fact it’s some hell of an ‘infinite space’.

All my love, especially to Geoff

Steven