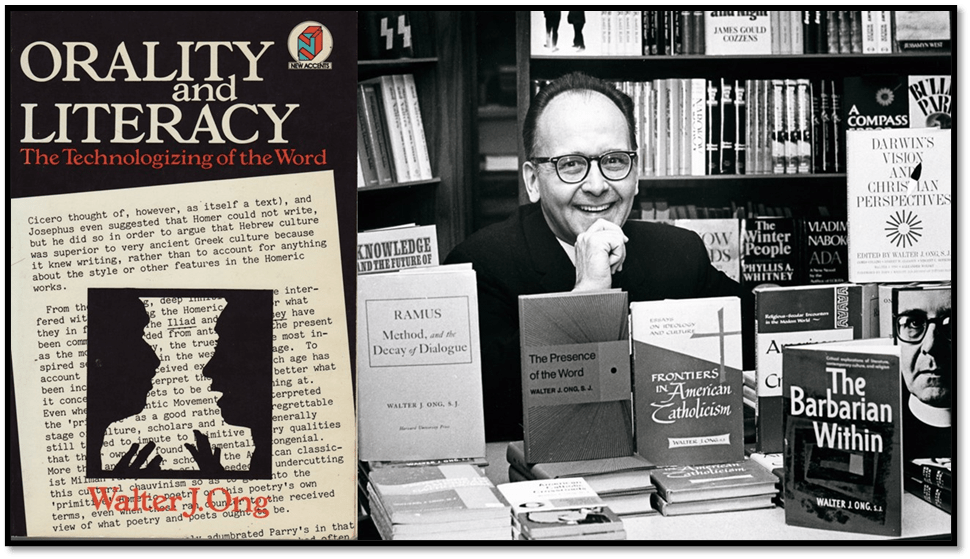

Father Walter J. Ong shook my world in 1982 with his book Orality and Literacy, wherein he tried to show us why we, seeped in literacy (even if we cannot or will not read because the characters to be read would still surround us and puzzle us, with either their potential to polysemous mystery or insistence) cannot even imagine a world where literacy did not exist. He made a broad characterisation of the differences in thought styles in such cultures. First of all, though, let’s admit that the binary contrast of orality and literacy is itself a fiction.

There is probably no culture where marks made on a blank surface or added to a pictured one did not play a role, although in a predominantly oral culture, it would have been a different role. But written or inscribed characters are almost certainly an old tradition. Hence the binary differentiations in thought style elaborated by Ong in the first chapter, which can be read now on the internet alongside pages from the rest of that great book, are also not rue binaries but extremes at the opposite ends of scale that are themselves (the scales that is) decidedly social constructions, with potentially arbitrary endpoints[1] But here are those binaries listed, each describing how thinking in an ‘oral’ culture, imagined as without literacy, differed from a literate one – where data was communicated by text rather than voice. Oral culture would be:

- Additive rather than subordinate

- Aggregative rather than analytic

- Redundant or ‘copious’

- Conservative or traditionalist

- Close to the human lifeworld

- Agonistically toned

- Empathetic and participatory rather than objectively distanced

- Homeostatic

- Situational rather than abstract

I will not try to explain the abstractions in this list, given the ease of access to the chapter and its fulsome explications in Ong’s beautifully clear prose, using often textual material to characterise what he discerns in them as ‘one preserving recognizable oral patterning’. Many of Ong’s points relate to the syntax of written language, including the use of the hierarchical relationship between main and subordinate clauses, effects impossible, or difficult to achieve in oral syntax. In the latter, each phrase is added to th next. Ong’s vison of the oral culture has its negatives – a homeostatic way of thinking is one that does not change its view of the world and one that does not favour generalisations of experience upon which the habits of ratiocination depend.

Yet it is a ‘homely world in his chosen view of oral culure-worlds – generous (‘copious’) rather than economical, unafraid of repetition and excess of signification. To be ‘close to the human lifeworld’, that is focused on active conflict where conflict feels necessary rather than suppression and subordination of surplus meanings perceived in that lifeworld (rather imagine the Gods at battle than an occluded and internal contest of mental consciousnesses of the world) and empathy and participation hold priority over regulated rationality and the mechanisms of ‘law’.

Ong’s defence of the ‘redundancy’ implicit in oral language use sets up an underlying binary that is the essence of his argument: that between what is natura, al in the lives of human animals and what is an inventive technology, involving an artifice which reconstructs nature in more efficient forms. Here is his lovely paragraph:

Since redundancy characterizes oral thought and speech, it is in a profound sense more natural to thought and speech than is sparse linearity. Sparsely linear or analytic thought and speech is an artificial creation, structured by the technology of writing. Eliminating redundancy on a significant scale demands a time-obviating technology, writing, which imposes some kind of strain on the psyche in preventing expression from falling into its more natural patterns. The psyche can manage the strain in part because handwriting is physically such a slow process—typically about one-tenth of the speed of oral speech (Chafe 1982). With writing, the mind is forced into a slowed-down pattern that affords it the opportunity to interfere with and reorganize its more normal, redundant processes.

There are assumptions here about what is ‘natural to thought and speech’ that are based on little more than the assertion of what Ong sees as ‘foundational truths’ about the natural essence of human life. Nevertheless the point gets made that writing has reorganised what subsisted before its advent. The time it takes to write justifies itself in achieving a compacted focused expression, less interested in inclusion of all than developing an ever more refined technocratic skill. One result may be a more precise scientific language but another is the highly complex sentences of Henry James, in which syntax mimes internal processes or ordering and disordering of consciousness in interactions between people which record a multiplicity of voices battling for supremacy over the meaning to be achieved in any one sentence.

I was once much taken with this theory. It seems to look back to some lost world of nature but doesn’t as a result depreciate the modern, for the prose of the New Testament and of revealed truth in Ong’s Jesuit faith is a prose in which the Word reorganises life in its own visible image, as text not merely sound. St. Paul is not a simple writer but a highly refined one, whose effects depend on the play of voice over written text. Take I Corinthians 13: 1, which has a complex syntax in the original Greek, even though the burden of its meaning is to compare learning at its most abstract and polyglot, with the natural virtue of agape, spiritual love for all.

Ἐὰν ταῖς γλώσσαις τῶν ἀνθρώπων λαλῶ καὶ τῶν ἀγγέλων ἀγάπην δὲ μὴ ἔχω γέγονα χαλκὸς ἠχῶν ἢ κύμβαλον ἀλαλάζον

In the King James version that love is rendered as ‘charity’, but the meaning is still bound up in a complex subordinate clause structure:

Though I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, and have not charity, I am become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal.

Corinth looking up to AcroCorinth

To start a sentence with a conditional clause (an ‘if’ clause in modern translations) is already to enter a realm of abstract meaning, to imagine a state of being that is no other than a thought experiment that contrasts an idealised image of great learning with a direct image of the grossest extremes of sounds in mass and volume in a company of musicians. The effect of the sentence is created by the continuous present tense (λαλῶ – lalo – I speak) compared to the complex present tense expressing an emergence of the true self from behind the pretensions of the speaker of many languages (even those of angels) – ἔχω γέγονα -e{ch}o gegona – I have become. The simple phrase ‘have not charity’, apparently subordinate, to the grandiosity on one side of it and onomatopoeic noise on the other becomes the main burden of the sentence – the absence that turns potential refined meanings into raw noise.

But the sentence from St. Paul is complex not because it has assumed the techniques of writing per se but that, because, using these techniques it renders something stronger than the additive, aggregative and redundant language of oral story, the sense that a ‘still small voice’ speaking of charity of love, can be more forceful than the fancies of a learned linguist and philosopher (who thinks they speak to angels) can overcome it and render it into meaningless noise. In a sentence like this the oral complements the written – in the onomatopoeia and assonance in the Greek for instance (λαλῶ chiming with the middle of ἀλαλάζον; the simple sound of natural feeling with the complex sound of the name of what is merely of minimal meaning – tinkling).

Ong really won’t do for our modern age, though he allows us to see such effects as I find immediately above. Reading is a technical skill but it involves more than an abstraction of what is particular and ‘close to the human lifeworld’. A beautiful sentence allows us to feel that life world complicated by the many voices that complicate it by interpreting it differently. These differences are not the simple binary of false and true but are alternatives deriving from differing subjectivities rather than the aggregating voice of one narrator speaking for the whole community.

Recently, speaking to my dear friend Joanne, for whom Geoff and I had bought Ali Smith’s Gliff (for her birthday – impertinent young woman that she is LOL!). She compared the experience of reading it with hearing it in an Amazon ‘Audible’ version. In brief, Joanne felt the narrator dominated the narrative and rendered the experience flat and unfruitful. Reading it she heard all the voices – including those silenced by our failure to know the voice of animals – and the experience was rich and extremely moving. Ali Smith, I know, would agree with her – she is the greatest writer of the orchestra of voices behind her novels that renders them polysemous (the theme of Gliff – see my blog at this link).

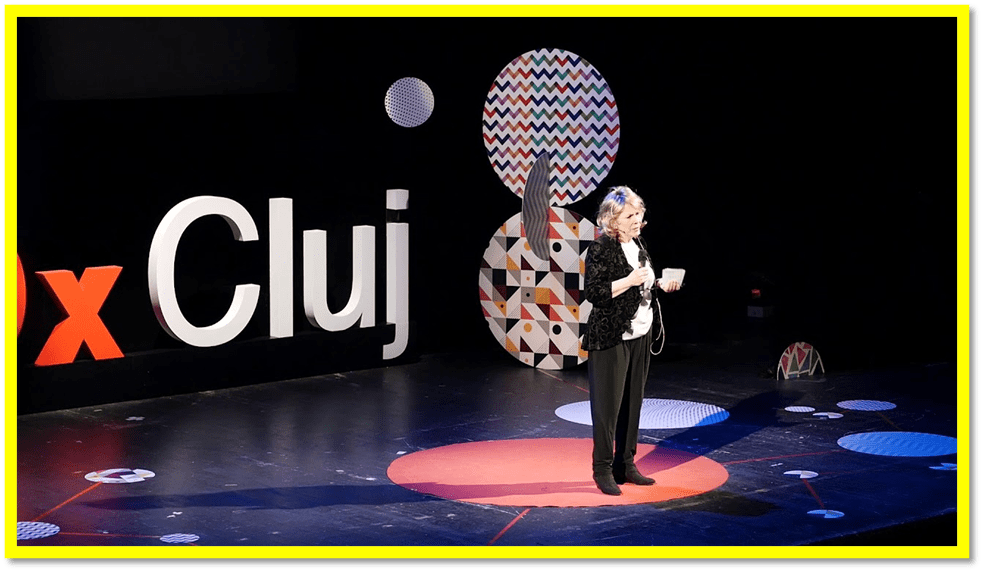

And Ong will not do as a theorist because we understand much more about the contrast of orality and literacy, as a scalar thing. Some text speaks directly – others indirectly, but all text other than the driest prose in poor science writing (not be it noted the very greatest science writing) is the container of many voices – a polyphonic structure in which voices contest each other – sometimes in the same sentence in prose with a complex shifting point of view. At its simplest the different voices are embodied in characters – though it is not simple for a writer to achieve this, at other times the prose bears those differences of voice in ways that fragment and counterpoint it – as in the very best of Virginia Woolf. The theorist who gets s nearest to this is not such a catholic (in many senses of the word) mind as Ong but is very much a good writer on the science she knows best – neuroscience. In a TEDx talk, Rita Carter tells us that children (babies even) learn speech (orality) so easily because the pathways are already laid down or prescribed in the brain. In describing this Carter uses some of the same binaries as Ong – the natural (or genetically wired in human brains) and the learned where the brain is in some ways reconfigured in its most plastic systems. Here is what speaking does:

…when you look at a brain that’s speaking, it’s fairly straight forward: if you see a dog, say. Information zooms to the back of the head, visual cortex, then sort of chunks forward. As it chunks forward, it picks up memories of what it’s looking at until by the time it gets to that blue area, which is the first of the major language areas, it is then able to put a word to it. And then it gets jogged on again to that next red area, Broca’s, and that’s when we remember how to say it. Quite literally, the motor area, which is that green stripe, is then instructed to send instructions to our lips and our tongues to actually make the word. That’s how speaking works. And, as I say, it’s natural, those pathways are there already. But reading is a very different kettle of fish. When we see abstract symbols written down, our brain has to do far more work..

The reference to the dog rather confuses the issue as do the ‘kettle of fish’ but linguistic inelegance aside, the point is beautifully illustrated – better if you have a passing acquaintance with brain anatomy.

The quotation above continues thus, showing that learning exploits different areas of brain to those we are accustomed to use (forget nature’ for a moment, for these plastic connections between unexplored brain areas are natural too. The concept of ‘theory of mind’ that Carter exploits in this talk is the very basis of how a child learns how to relate to a social world of different ideas, feelings and motivations for action. Here, she shows that reading opens up ‘complicated networks’ in the brain: complex but not artificial.

When we see abstract symbols written down, our brain has to do far more work. It actually has to, when we are learning to read, we have to create all those new connections in many, many different parts of the brain. You can see the red bits, or the lit-up bits. You can see these aren’t clear, easy, one-trap pathways. These are really complicated networks that are being formed in the brain when we read. So your brain is doing a lot more work, it’s connecting far more parts. If you like, it’s a more holistic experience. It forces you to use parts of the brain that aren’t usually used. More than that, the reason, or one reason why it’s so widespread, is that when we read things about somebody doing something, run for their life or they’re screaming or they’re frightened, what happens in the brain of the reader is that those same bits of the brain that would be active if they were doing it themselves, become active.

This excellent piece (listen to it (Carter is a great talker)) really speaks of Joanne’s different experience of hearing one voice read Ali Smith’s Gliff, and reading the book itself for herself. As Carter says Joanne is actually experiencing all that multiplicity in reading rather than listening to one unitary voice speaking a story. Reading has made her brain and its complex configuration of intersecting sensation, thought, feeling and action (that mimes the ‘touch’ of something real – even visceral (Cathy on Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights is Carter’s example) we feel in good prose)). Here is Carter’s clear voice, again:

Because the important thing about reading is that you’re not just learning what’s going on in that person’s head. You, too, to a certain extent are experiencing it. And there’s a very big difference there. It’s the same with everything. With pain – if watch or read about somebody in pain, the same bits of the brain that would be active if you were feeling the pain will become active as well. And some people feel this so much that they actually do feel and report the pain. Same with anger, same with any emotion, same even with quite complicated intellectual things, like judgments, moral judgments, and so on. [2]

All my love, especially to Joanne

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Ong, Walter J. 1982. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Methuen, pp.31, 37-49.Available at: https://newlearningonline.com/literacies/chapter-1/ong-on-the-differences-between-orality-and-literacy

[2] See & hear the talk at: Rita Carter on reading – Search Videos at https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=Rita%20Carter%20on%20reading&