Act 1 Scene 5 is pivotal in Shakespeare’s play Hamlet for the eponymous character and the progress of the play’s plot itself, partly because it makes clear that the character of Hamlet is the substance of the plot of Hamlet as a play. If plot distributes the actions that take place in a play, those actions are scheduled in large part by the tensions in Prince Hamlet’s character and situation, and it is Act 1 Scene 5 that makes that clear. Hamlet is oft made out to be a Revenge Tragedy of the kind that constituted a genre in the Elizabeth and Jacobean repertoire of the plots of plays, but criticism has never been happy with that naming of the play as if it were from that typical genre, as the Wikipedia entry link to the genre makes clear. But the lines that have been singing in my head recently are these from as near the end of the scene as you could get.

The time is out of joint. O cursèd spite

That ever I was born to set it right! [1]

The lines come to me as they do to any person born after the advent of a ‘shy democracy’ such as that we have in the United Kingdom. The concept of a ‘shy democracy’ refers to a form of governance that has not yet been fully realized or articulated for in the United Kingdom democracy is seen as conformable to elements of governance based on principles that are in some way contradictory to notions of the equality of persons implied by democracy. In truth there never was such a pure system even in the ‘direct democracy’ of Greece. Extant democracies still rely in practice on the prescribed social status of certain groups or individuals – prescribed either by inheritance through birth (as in monarchies and aristocracies) or by supposed merit, which when validated tends to become affixed as a constant, which merit truly never can be, being a variable by nature, and some even turn merit into a birthright, as in the case of Bonapartism in nineteenth-century France. It starts as a case for the rule of a single individual on his supposed merit as a military leader [or businessman i tne case of Donald Trump].only to become a right to govern as a hereditary dynasty. Meritocracy in practice, if not in theory (if such a theory exists in any real way), is anyway liable to become the rationale of new emergent aristocracies, oligarchies, and even monarchies. Attainment status tends to be a status as difficult to change once established as the right of birth in feudalism.

Nevertheless, we like to think we live in a society where individuals think, feel and sense the world in much the same way with an equal amount of rights, responsibilities and duties as the next person irrespective of status at birth. When I first read Hamlet, the character’s famous words rang like a statement of existential angst: why was I ever born if birth meant that I felt responsible for changing the state of society I was not responsible for making it be what it was at the time of my birth, which I also did not choose and hence cannot be responsible for.

It is as if society were a body whose limbs had become dislocated and it was holding me responsible (or so I thought) for correcting the slipped joints in each of its limbs back into articulation and purpose. This existential angst is the Hamlet of the Romantic period onwards, and that is why Samuel Taylor Coleridge thought he had a ‘smack of Hamlet’ about his own character. Each person feels compelled to act to better the world in some way but feels all capacity to action stilled by a tendency to overthink things before acting, being ‘sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought‘.

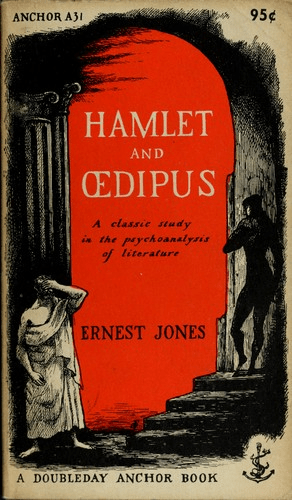

There is certainly that element of Hamlet as a character in Act 1, Scene 5 where Hamlet wants not to act to revenge his murdered father, even though that father rises from the dead to demand he does just that in the scene. Freud saw this scene as typical of the Oedipus complex – the son hates and has desired the death of the very father he feels he ought to love and obey. Ernest Jones, the leading light of the British Psychoanalytic Society, wrote this idea up for Freud in a famous essay. There he says that his Oedipal hatred for his father and sexual attraction to his mother, Gertrude, though not recognised by him, makes him express his ambivalence to his father by forcing him NOT kill the man who killed his father and married his mother, for that, like Freud’s version of Oedipus, is precisely what he wanted to do himself.

This version of Hamlet equally expresses an existentialist crisis but this time in terms of the character’s complex feeling about the beings who gave him birth, and whom he cannot think clearly about and hence hates the feeling that he was born to’set it right’ – ‘it’ in this case being the problems of what Freud called the family romance; that sexuality is formed on the forbidden choices children make of a sexual object.

Certainly the ghostly father – the dead King Hamlet senior acts like a terrifying father, even calling his son a ‘fat weed’ (the theory is an obsessive weight-gainer is often invoked in the criticism – acts like a terrifying vampiric version of a father> Hamlet talks as if his action will be swift when he discovers from his ghost father who killed him. He will ‘sweep to my revenge’. The GHOST expresses himself strangely in reply. He does not say he is a ‘fat weed’ but that he would be does he not ‘sweep to revenge’ as promised:

GHOST I find thee apt;

And duller shouldst thou be than the fat weed

That roots itself in ease on Lethe wharf,

Wouldst thou not stir in this. Now, Hamlet, hear.

’Tis given out that, sleeping in my orchard,

A serpent stung me. So the whole ear of Denmark

Is by a forgèd process of my death

Rankly abused. But know, thou noble youth,

The serpent that did sting thy father’s life

Now wears his crown.

HAMLET O, my prophetic soul! My uncle!

But, as we all know, Hamlet delays his sweeping to revenge. Jones takes his case for an Oedipal reason from the fact, and others, that the Ghost goes on to blame his murderer less for his own murder y him but because he usurps his own sexual and marital role with Gertrude.

Ay, that incestuous, that adulterate beast,

With witchcraft of his wits, with traitorous gifts—

O wicked wit and gifts, that have the power

So to seduce!—won to his shameful lust

The will of my most seeming-virtuous queen.

O Hamlet, what a falling off was there!

From me, whose love was of that dignity

That it went hand in hand even with the vow

I made to her in marriage, and to decline

Upon a wretch whose natural gifts were poor

To those of mine.

But virtue, as it never will be moved,

Though lewdness court it in a shape of heaven,

So, lust, though to a radiant angel linked,

Will sate itself in a celestial bed

And prey on garbage. [1]

That is a most rabid speech, rabid in its misogyny and patriarchal control and binding of the ion’s will into the deepest shame lying behind the Name of the Father. It is all spoken in a terrible binary of sex as aither that performed on a ;celestial bed’ or that made of ‘garbage’ (see its early etymology here)

But there is another reading possible of this scene for the problem of Uncle Claudius’ bedding of Hamlet’s mother is that, though it is unspoken, she might bear a son to Claudius, now the King in King Hamlet’s stead, whose birth will disinherit Hamlet Junior, the Prince. Now that might have considerable advantages for Hamlet who is uncertain of his wish to be a King. Being a King by inheritance of noble birth can be a burden. When Hamlet says: ‘O cursèd spite / That ever I was born to set it right! [1], he may not mean, as us moderns want to think – Why was I born to this mixed up family? I didn’t ask to be? (a version of Jones’ interpretation). Neither may he mean: ‘Why was I born if being born means taking responsible existential choices about action (as Coleridge read him I think)’. Indeed he may mean something that would be a very clear issue to the Renaissance ‘Prince’ Hamlet actually was – whatever the folklore history he is taken from – but: ‘Why was I by born in a royal line whose responsibility it is to set things right during the time of my coming reign?’

If the latter is the correct reading then Hamlet is questioning a social order in which the being you are is determined by the accident of birth in the genetic line of a dynasty of Kings, and wanting out of it – to be, as it were not the one responsible for ruling the Kingdom and steering the ship of state out of troubled waters, or curing its dis-articulated and disjointed limbs. And when people question the greatness of Shakespeare I think of the polysemous strands that interpret those two lines that I have quoted here. There is no doubt that to me that the final reading I give of the reference to the problems of in whist circumstances of genetic inheritance you were born, and the duties such genetic inheritance entailed on you were primary in Shakespeare’s mind, and of his contemporary listeners at the time, but, because he is Shakespeare he saw his time in a massive semantic shift where the modern meanings others discover later in history are implicit – the mounting problems of a new form of family structure for instance that predicated the Oedipal reading, including a new prominence given to female roles (soon to be cast down again and again when challenged) and a new form of individualism that Stephen Greenblatt calls ‘self-fashioning’. That is one reason people quote the verse Ben Jonson made for the First Folio of Shakespeare’s collected plays that he is not of his time but for all days

He was not of an age but for all time!

...

And make those flights upon the banks of Thames,

That so did take Eliza and our James!

But stay, I see thee in the hemisphere

Advanc'd, and made a constellation there! [2]

Ben Jonson is crafty to show the way Shakespeare spanned the thinking of two consecutive dynasties – Tudor and Stuart, but is silent about how that in itself took cunning to retain his pre-eminence in very different courts. But the point is that id Elizabeth I and James I were stars, Shakespeare was made for a constellation of forms of bright stars of leadership and governance through time. He like a translated human (Orion perhaps) has made his abode among near immortal things above the moon. Did Arnold refer to that in his poem on Shakespeare:

Others abide our question. Thou art free.

We ask and ask—Thou smilest and art still,

Out-topping knowledge. For the loftiest hill,

Who to the stars uncrowns his majesty,

....

Self-school'd, self-scann'd, self-honour'd, self-secure,

Didst tread on earth unguess'd at.—Better so!

All pains the immortal spirit must endure,

All weakness which impairs, all griefs which bow,

Find their sole speech in that victorious brow. [3]

The point is there is no ‘sole speech’ in Shakespeare – only the greatness in which the polysemous on which passing time works across temporal and spatial cultures – between distances of culture and .time (even fashion but more than that – deeper transformative value systems). This is why I think Shakespeare still has things to say about culture – why his racism undermines itself, his ideologies created for tyrants become their own means of critique

With love as ever

Steven xxxxx.

___________________________________________________

[1] Hamlet Act 1, Sc.5, lines 210f. Available in Folger Shakespeare Library online at https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/hamlet/read/1/5/

[2] See Jonson’s poem at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44466/to-the-memory-of-my-beloved-the-author-mr-william-shakespeare

]3] Matthew Arnold ‘Shakespeare’ in full at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43603/shakespeare-56d2225fc8ead