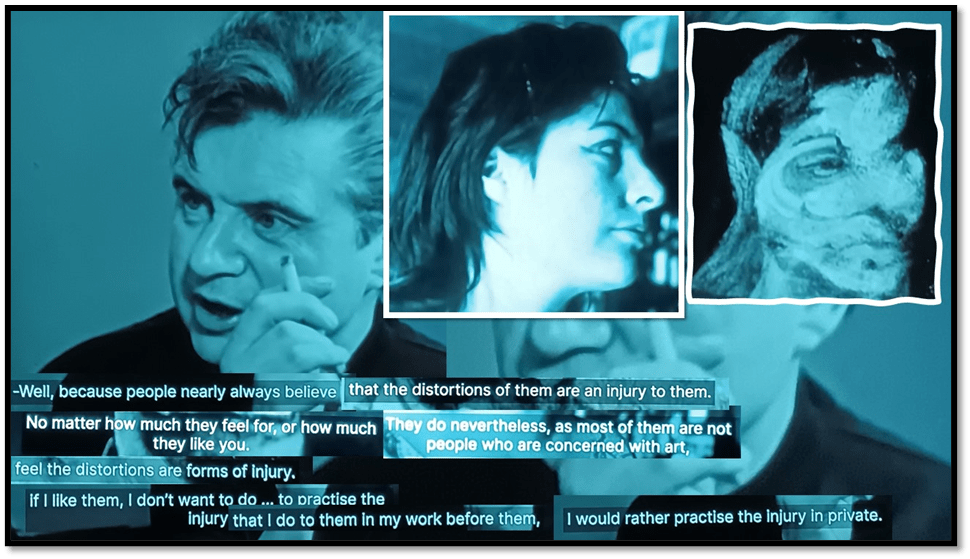

Bridging Gaps in Personal Learning No. 3: Bacon claimed that the role of art was not to create a ‘likeness’ of what meets the eye in looking at his sitter but to discover ‘a deeper sense of the reality of the image; by finding a way to ‘unlock the areas of feeling’ that lead to that image. On the way he discovered that some of his sitters felt, not least his working class lover George Dyer, very hurt by these images of them. Michael Prodger in The Critic (online) cites Dyer thus: ‘he never liked them: “I think they’re fuckin’ ’orrible, really fuckin’ orful,” he told Bacon’s friend, Michael Peppiatt’. Prodger concludes that if Bacon believed that “a thing has to arrive at a stage of deformity before I can find it beautiful,” Dyer didn’t’.[1] Why should Art, truth, and beauty paradoxically require paradoxically deformed, duplicitous, and deformed images to be seem real and not superficial to an artist?

This blog is based on the following remit in an earlier planning blog (at this link):

| Topic | Comment |

| Then the blog on the Bacon: The Human Presence exhibition at The National Portrait Gallery. | Back on course. |

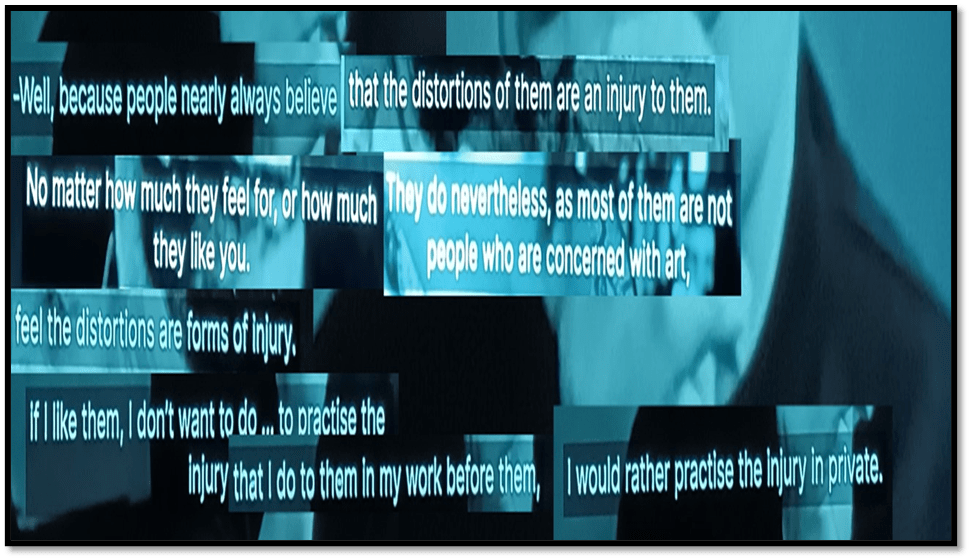

In my last piece on Bacon, I examined why Bacon praised Van Gogh for saying, “What I do may be a lie … but it conveys reality more accurately’.[2] The root of the idea here lies in a paradoxical confluence of opposed abstract binaries – like, for instance that the deeper we search for ‘truth’ the more it may look on the surface like the opposite of truth – a lie. Likewise the deepest sense of beauty may be what is considered ugly, the most appealing of aesthetic forms will seem ugly to the ‘superficial’ (like those Bacon said amongst his sitters , and certainly including Dyer, who were ‘not people who are concerned with art’). No doubt Dyer felt that Bacon’s images were ‘fucking ‘orrible’ because they were meant, as he saw it to look like him and to his mind they were not the man he wanted to see in either his own or the public gaze.

For some esteemed Bacon critics, there is a quick answer to why the truth and beauty of art are paradoxically both lies and horribly ugly. Chris Bucklow has long thought of Bacon as a ‘projectionist’ of both the unconscious representations of what the world is in inner perception and in the even more active dynamic of the unconscious will or wish. In 2021, he spoke of the belief in Bacon, and perhaps in him too, that:

… the creative act is discovering or accepting something that is given. Bacon’s need is to be a passive partner, a receptive submissive spouse to the projectionist.[3]

The very ugly and unseeing image of the submissive spouse to a male muse is strangely apt here, but no less unbecoming for a critic (especially one so psychoanalytically oriented as Bucklow) to use without some kind of scare quote commentary. It helps me though to begin with the nearest person to whom Bacon was spouse (or was the dynamic of the pair relationship otherwise vis-à-vis conventional gendered power relationships that pose under the name ‘marriage’), George Dyer.

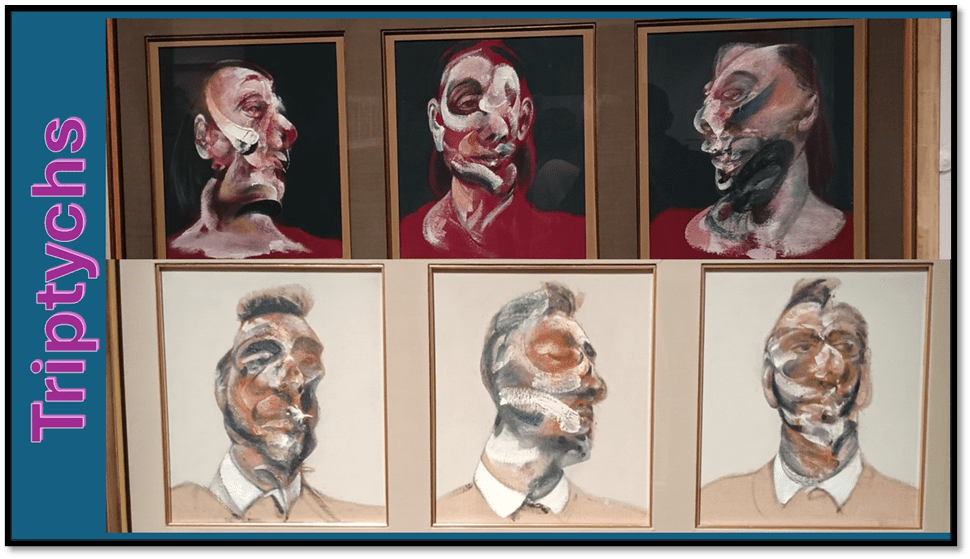

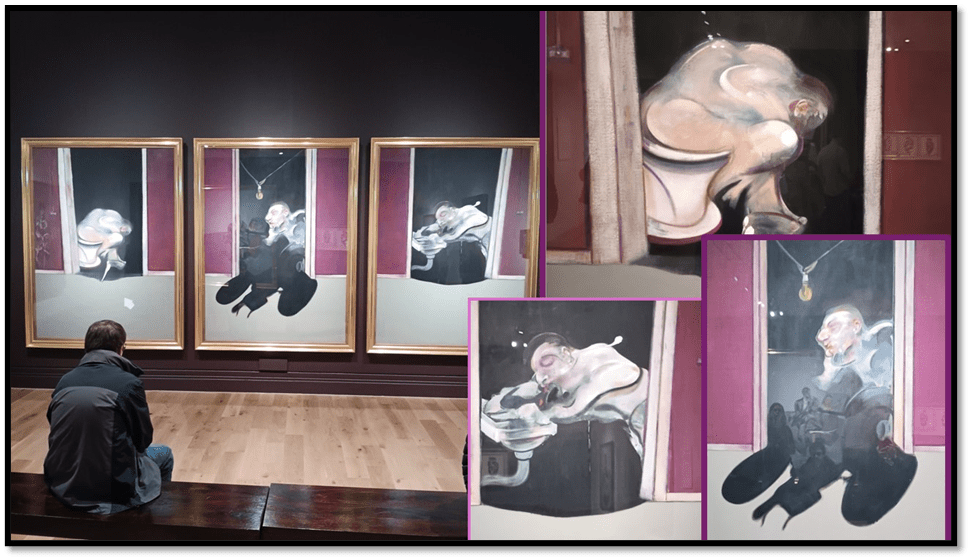

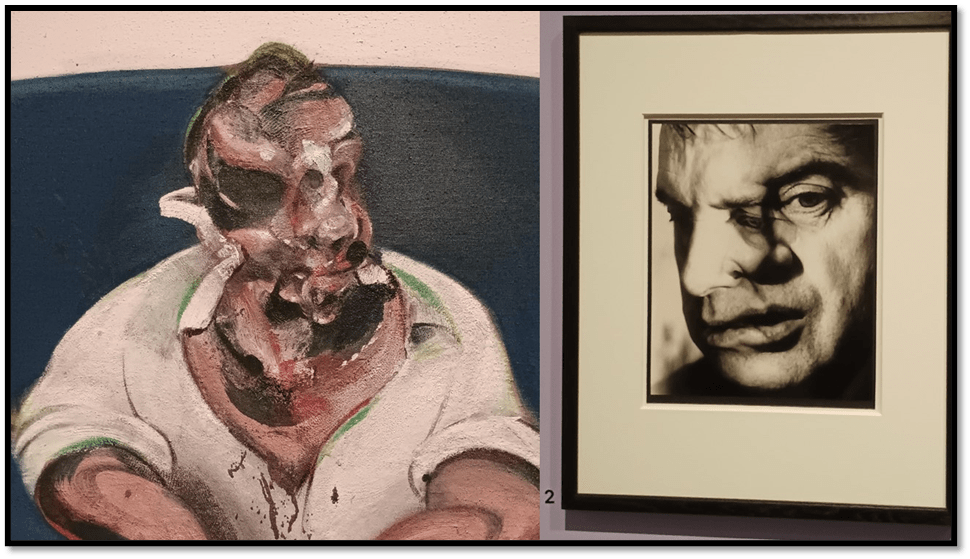

Although Bacon rarely used long sessions with sitters; preferring to use photographs taken for the purpose, Broadley says that ‘in Dyer, he found a patient and unimposing sitter who could sit for hours’.[4] The John Deakin photograph above shows an attractive man who knew that about himself, ready to show his wares for as long as it takes. Yet far from showing a man smiling, the images of him by Bacon (the lower set in the slide below (The Three Studies for Portrait (on light ground)) – the upper set are The Three Studies Of Muriel Belcher) look alarmed, in danger or in the aftermath of a violent blow or slap, though the middle image is, in my eyes strikingly beautiful. But it also looks as though in the aftermath of a dynamic slap or punch to the lower jaw.

Let’s look at that central figure more closely.

Much of the dynamic of this picture comes from the two arc brushstrokes in thick impasto that swell the cheek and seem to send the head behind them rocking back as at the effect of some force that has just been applied, although it does not exist yet as an effect of bruised flesh. Nevertheless the peculiarity of the impasto, especially near George’s thick lips and under a reddened eye that looks as if it is swelling already into a bruise.

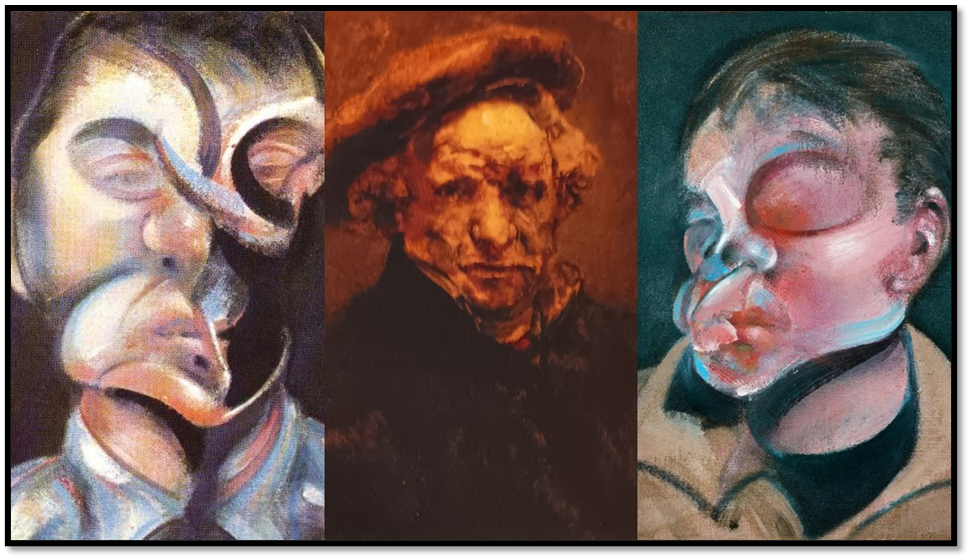

Similarly, the distorted angle of the neck shows similar force, partly created by the dislocating effect of an impasto patch across the neck under the hair and above the jumper. The coiffed hair rhymes in shape with these more obscure marks – all add to the patterned beauty. As for the bruised eye, compare it with the self-portrait by Bacon on the right below, which registers the effect on Bacon on a night of violence inflicted on him by his first love, Peter Lacy. There is no doubt that such damage to frail flesh in paint impasto effect may have come from Rembrandt considering the injury to him done by the ageing process and poverty following his bankruptcy.

The idea of love experienced in relation to injury played a part in Bacon’s life of course with his volition, as if injury alone, and the clear wish to inflict it was an evidence of loving, whether it mediated hate cognate with that love (as Freud posited) or not. It is more than hate, of course, if it is that: it is violent injury and it is shown in physical reconfiguration of vulnerable body parts, especially faces, although not only this as we see below in the case of Henrietta Moraes, who is so badly bruised that the bruises appear a permanent colouration of specific body parts:

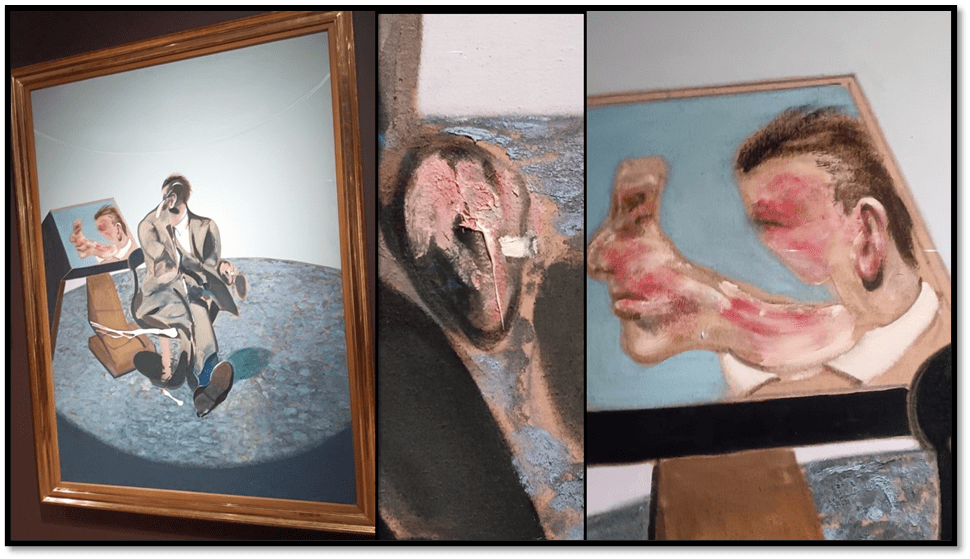

It is as if injury were an active process of affirming the truth and beauty of love and of the art that embodies in paint these loved bodies and portrait busts. Take, for instance, the greatest Dyer portrait before the posthumous triptych, Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror (1968).

The severed wrist holding a cigarette is not the most obvious of the ‘injuries’ inflicted on the figure. The portrait bust is entirely split from to bottom, and its facial features reddened and scarred – perhaps with fresh bruising. The figure has a bizarre transverse orality as if the split in the top of the head were another mouth or orifice opening. The frontal features have the shape of a meat chop. The non-reflected head is disfigured in a way that does not quite rhyme as it should with the ‘mirror’ image. The mirror itself does not look like a mirror but a screen of sorts.

His legs either bend or lie in stricture, perhaps even melt. His body parts have the wrong proportion, even more emphasised by shadows of themselves, especially the foot pushing out to the picture frame on the right. There are white paint slashes across the picture as if the representation of bodily injury had to be extended into additional damage to the paint surface.

And look again at the way Bacon theorised this in the BBC interview with George Peppiatt at the head of this blog. Here are just the words themselves – very famous words where art and injury become essential to the transformation of representations of reality into aesthetic images:

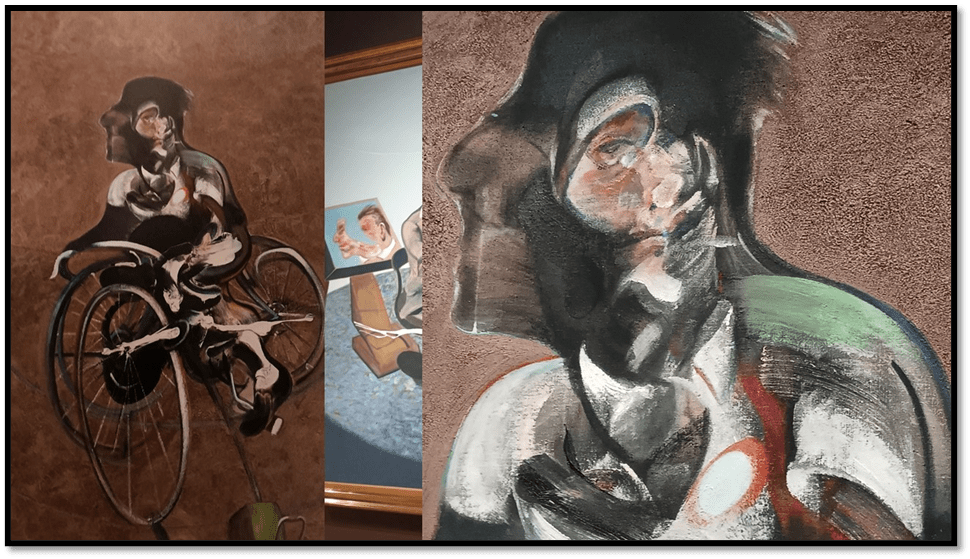

The idea of truth and beauty as an injury involving the actions of the most private self of the artist are crystal clear, as is the idea of ‘practising the injury’ as if it were a banned act, as for most of his life his sexuality was. He took this to wonderful extremes in the wonderful Portrait of George Dyer Riding A Bicycle (1966).

People who ought to know say the face looking out of the sides of George’s head is in part a self-portrait of Bacon. Even if this is so, I wonder if it is pertinent beyond the effect it has of creating a figure containing its own alienation, as this one does. It rides badly this figure not only because the back wheel is buckled as if it would be in the accident that seems likely, but because George lacks concentrated direction. The face to the side is like something intruding on the automatic nature of his cycling. Again the white slashes cut the bike up, though they seem here more functional than in the mirror portrait. Everything about the self, including the driving has a double, if not a triple form. The body has absorbed its own shadow even. It is beautiful – the process of ‘injury’ however is prepared for in the art and set in progress rather than being complete.

And, of course, the finest George Dyer paintings is the final triptych of his death process , a self in triplicate is entirely evacuated in these pictures as excremental matter, with even bat-like shadows counting as such. This is love. This is ART.

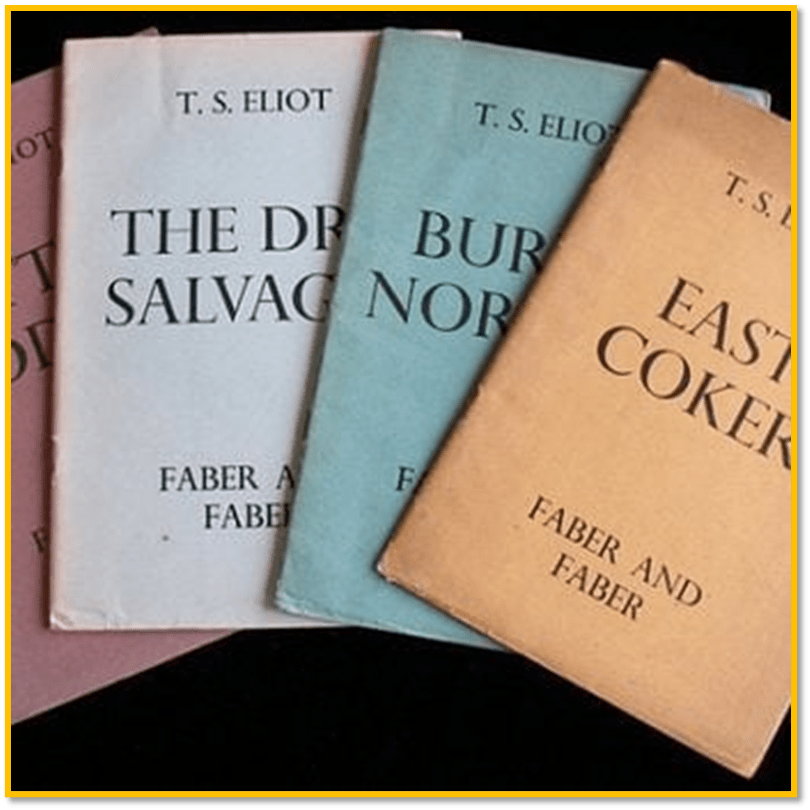

Yet in being for Bacon expression of art and love, they still do injury to us as viewers. As I say in my title: Bacon claimed that the role of art was not to create a ‘likeness’ of what meets the eye in looking at his sitter but to discover ‘a deeper sense of the reality of the image; by finding a way to ‘unlock the areas of feeling’ that lead to that image. On the way, he discovered that some of his sitters felt, not least his working class lover, George Dyer, were very hurt by these images of them. Michael Prodger in The Critic (online) cites Dyer saying that ‘he never liked them: “I think they’re fuckin’ ’orrible, really fuckin’ orful,” he told Bacon’s friend, Michael Peppiatt’. Prodger concludes that If Bacon believed that “a thing has to arrive at a stage of deformity before I can find it beautiful,” Dyer didn’t’.[5] Reaching the stage of deformity is a necessity of art. Bacon believed that not only he but T’S’ Eliot and Euripides thought like this and that this stage of deformity was the more to be sought after the truths revealed by war and political Fascism. Indeed in Part Iv of East Coker in The Four Quartets by Eliot, the artist is surgeon, inflicting pain and injury as part of the process of healing or reparation, though there is no pretence that healing is totally redemptive:

The wounded surgeon plies the steel That questions the distempered part; Beneath the bleeding hands we feel The sharp compassion of the healer’s art Resolving the enigma of the fever chart. Our only health is the disease If we obey the dying nurse Whose constant care is not to please But remind of our, and Adam’s curse, And that, to be restored, our sickness must grow worse. The whole earth is our hospital Endowed by the ruined millionaire.[6]

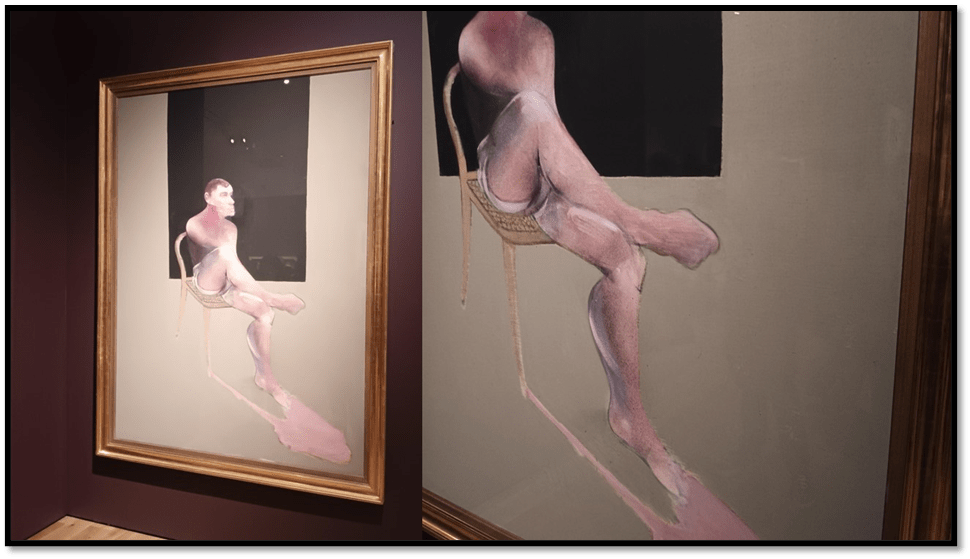

In a earlier blog I asked you to consider that what Bacon takes from Van Gogh too is a sense of reality conveyed not only as ‘lie’, a fiction, but also damage evoking splits in figures, uneasy shadows. I even asked this: ‘But do consider how the shadow in The Painter On The Road to Tarascon is like a spillage from the figure,. This motif in shadow painting is taken very much further as in the famous painting of the late reluctant lover and heir of Bacon, John Edwards. The flesh pink tones emphasis young well-blooded flesh but flesh so viscous it bleeds from itself without turning into real blood from the body’s interior. The boundaries of Edward’s body are compromised. Even the chair leg he sits upon is part of his flesh and part of the spillage that is its and his shadow.

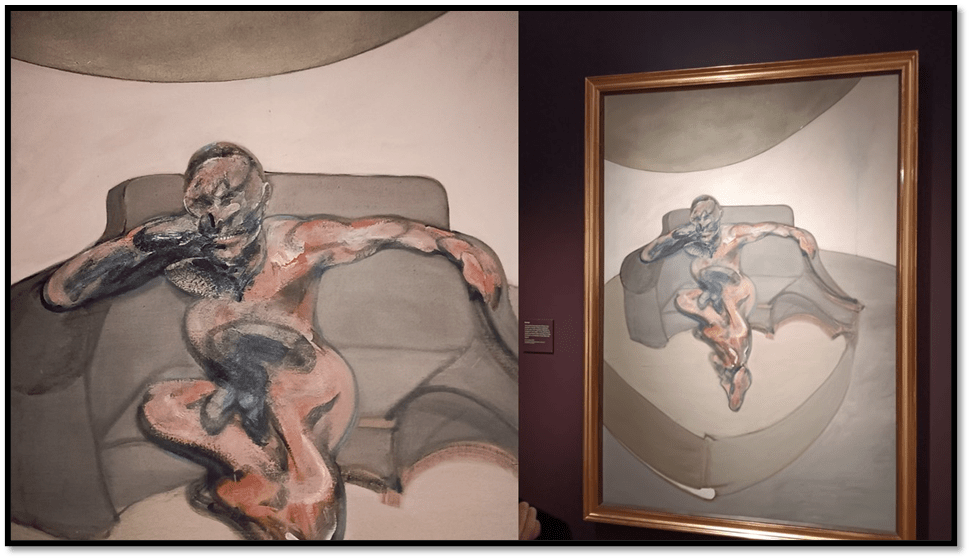

In the diptych below arbitrary colour has meanings. I don’t dare here to name the ones I see. Colour, framing both the figure and the ground and turn Lucian Freud inside out, just as he is forced to turn not only from fellow-artist, to model, to (almost – I see it anyway) ‘rent boy’. Everything in this painting does an injury to Lucian Frud but in doing so it attempts healing, for if alone, Freud must offer himself sexually by pose and expression, in the second he is the analysand in a psychoanalysis, his wound being in part covered (the blood read of his couch) by healing greens, the back of a green chair containing the proponent of analysis – could it be Lucian’s grandfather, Sigismund / Sigmund , or is it Bacon? N o matter – for the en-couched Freud seems to be fiddling with his phallus, masked by the psychoanalyst.

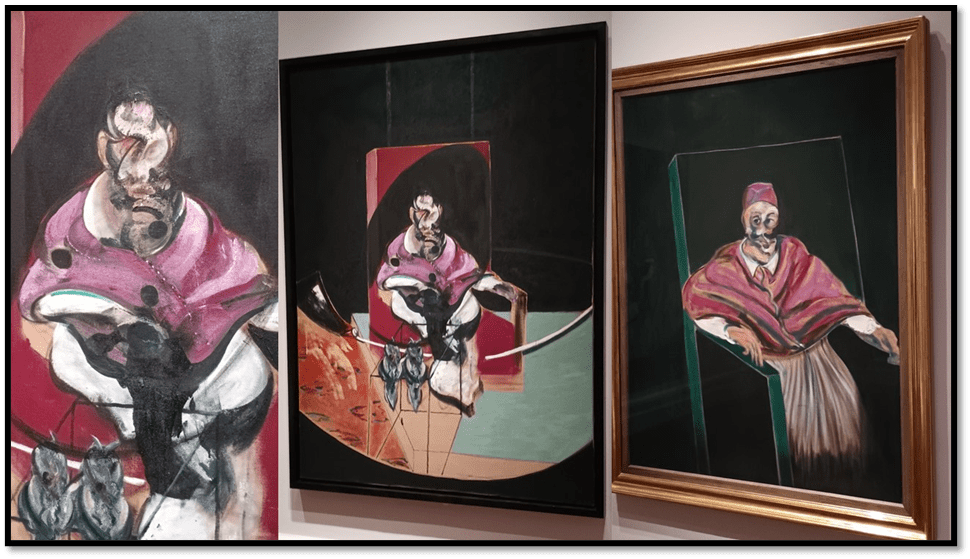

Of, of course, the injury that art is a means of showing art’s own need for healing as in so many screaming Popes showing the stark reality beneath Portrait of Pope Innocent X , an oil on canvas portrait by the Spanish painter, Diego Velázquez. The injury is required to assert the true corruption underlying this man, even in the very early portraits mainly featured in this show.

Sometimes a truer meaning arises from natural features transformed into ugly weapons such as is the penis of Peter Lacy in the 1962 Portrait. Lacy is almost an allegory of disease. As Bacon said of that relationship:

Being in love in that way, being physically obsessed with someone, is like an illness’.[7]

This is the face not just of deformity but allegorical evil.

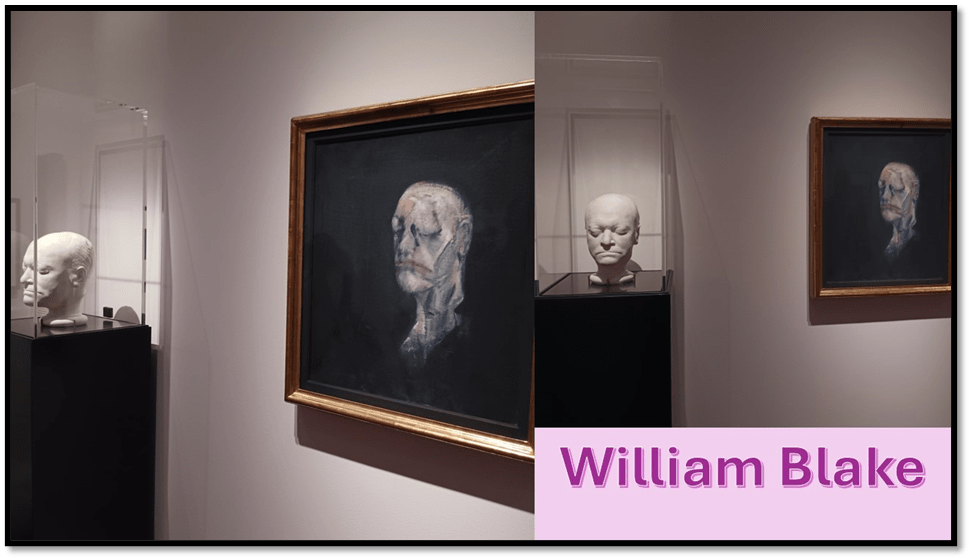

Sometimes the disfigurement is an act of love as in the exquisite portrait rendering of William Blake’s death mask. It gives ghostly life to what was dead to show Blake’s continuing effect as a poetic moralist, such as I believe Bacon too was in his art.

Of course, among Bacon’s arch-demons was Bacon himself as in the wondrous Study for a Self-Portrait (1963) – a detail is on the left in the collage below. But ugliness here is more reality than allegory as I think was the case with Lacy above. We see the face not disfigured necessarily externally by violence – though Bacon encouraged that to say the least – but the real multiplicities that are Francis Bacon asking for expression simultaneously. This exhibition excels with photographs of Bacon and one tells the same tale (below right). It is Jorge L:ewinski’s portrait made up of multiple viewpoints of the artist’s face in double exposure – much like Bacon’s version of portrait cubism. The ‘blurring and distorting’ as described by Georgis Atienza in the catalogue are not I believe merely there resemble ‘his own painting style’, they also help us see that self is a very difficult thing to comprehend precisely because it is not constant and unitary but situational in time-space and therefore multiple.[8]

Have I met my remit:

Then the blog on the Bacon: The Human Presence exhibition at The National Portrait Gallery..

Bye for now,

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxx

_____________________________________________________

[1] Michael Prodger (2022) ‘A tawdry death imitating art: Francis Bacon’s turbulent love for George Dyer is visible on the canvas’ in The Critic (online) [March 2022] Available at: https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/march-2022/a-tawdry-death-imitating-art/

[2] Rosie Broadley (2024: 17 ‘Francis Bacon: Human presence’ in Rosie Broadley (ed.) Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications., 10 – 22.

[3] Chris Bucklow (2021: 20) ‘Bacon’s Afterlife’ in Martin Harrison (Ed.) Francis Bacon: Shadows London, The Estate of Francis Bacon with Thames & Hudson, 18 – 35.

[4] Rosie Broadley (ed.) (2024: 155) ‘George Dyer’ in Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications., 154 – 163..

[5] Michael Prodger (2022) ‘A tawdry death imitating art: Francis Bacon’s turbulent love for George Dyer is visible on the canvas’ in The Critic (online) [March 2022] Available at: https://thecritic.co.uk/issues/march-2022/a-tawdry-death-imitating-art/

[6] See T.S. Eliot – Four Quartets: East Coker | Genius https://genius.com/Ts-eliot-four-quartets-east-coker-annotated

[7] Rosie Broadley (ed.) (2024: 113) ‘Peter Lacy’ in Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications., 112 – 121..

[8] Georgis Atienza (2024: 192) ‘Picturing the Artist: Camera Portraits of Francis Bacon’ in Rosie Broadley (ed.) Francis Bacon: Human Presence London, National Portrait Gallery Publications., 181 – 205.