Who would have thought that ‘screen time’ is a phrase that could be discussed on Wikipedia but it is!. That discussion focuses on the bad effects on the developmental physical and mental health of children but adults are considered as in this extract, which makes the point that screen time for adults is divided between mandated use of time in work roles and apparently voluntary usage for leisure and development of interests, hobbies or crafts. Their analysis of costs to physical and mental health applies, of course, to adults too, although with caveats regarding the evidence:

There is no consensus on the safe amount of screen time for adults. Many adults spend up to 11 hours a day looking at a screen.Adults many times work jobs that require viewing screens which leads to the high screen time usage. Adults obligated to view screens for a means of work may not be able to use screen time less than two hours, but there are other recommendations that help mitigate negative health effects. For example, breaking up continuous blocks of screen time usage by stretching, maintaining good posture, and intermittently focusing on a distant object for 20 seconds. Furthermore, to mitigate the behavioral effects, adults are encouraged not to eat in front of a screen to avoid habit formation and to keep track of their screen use every day. Specialists also recommend that adults analyze their daily screen time usage and replace some of the unnecessary usage with a physical activity or social event.

And there you have it – the rationale for this WordPress prompt, which encourages adults to ‘analyze their daily screen time usage’, perhaps in a prompted question, and to strategise how to ‘replace some of the unnecessary usage’. But wait on a minute. WordPress prompts promote such healthful activity indeed but where – on a screen, expanding ‘screen time’ inevitably and perhaps even without conscious awareness in the process. And in the end, I suppose the issue developed in such public accounts of ‘screen time’ is that it is a relative concept set against other uses of time – in nature for instance, – and competing with it. That however is already too simple an idea. for it pretends that time is with one thing rather than another, ignoring how each thing on which time is used is often mediated by objects or mental concepts from other domains. For instance, Wikipedia says: ‘More screen time generally leads to less time spent in nature and therefore a weaker connection to it’.

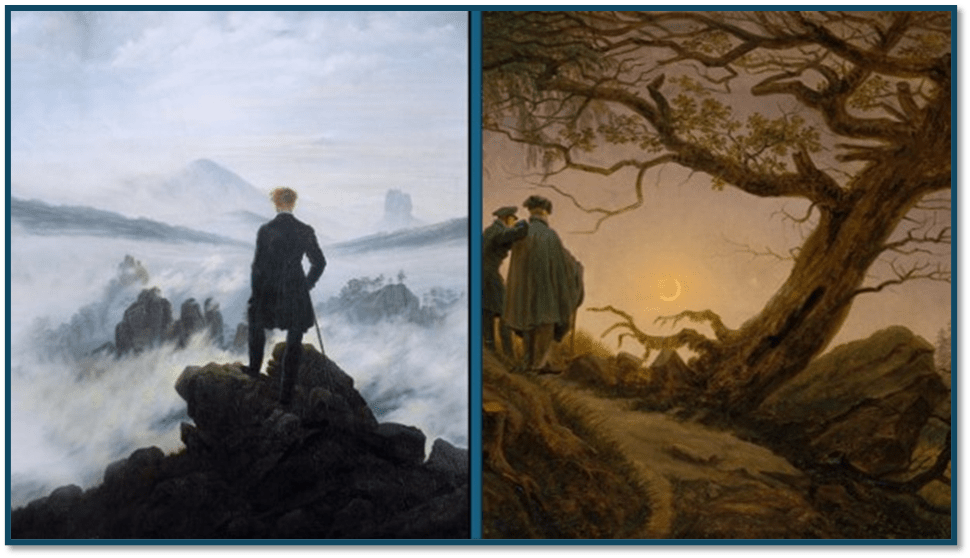

If only time were parceled out like that or the strength of our ‘connection’ to Nature thus easily made – by direct contact and by that alone. Nature is the the most mediated of concepts – mediated by human influence on it – both in the creation and destruction of habitats and the rendering of nature into plastic forms we call ‘landscapes’ or ‘scenery’. Books once mediated Nature to us – from books on landscaping, geological interference in mining for instance and finally in art – visual and written. Did Caspar David Friedrich waste time he might have spent nature by recreating figures of men, usually men , viewing and contemplating it in the flesh. For though they are imagined doing so, was Freidrich or the viewer spending time in an art gallery or contemplating the picture at home if they owned it:

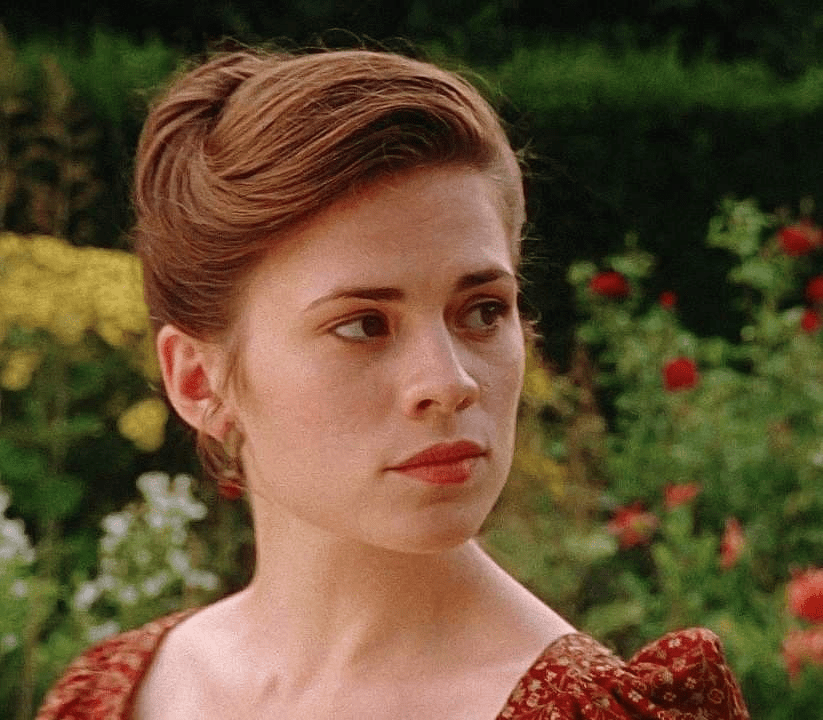

In effect, the Wikipedia comment might as well berate Friedrich for spending so much time at his easel rather than in nature. And how much do we believe anyway that the fashionably dressed gentleman in the picture on the left of the collage above actually spent time climbing a mountain to get where he was and still remained as good looking. Is this really nature. Let’s go for a writer, who though she admired (up to a point) the Romantic appeal directly to Nature in Byron and Wordsworth, was somewhat ironic about why people wanted to spend time in it. Here is a conversation between the urban socialite Mary Crawford with the ubiquitous Austen-like Fanny in Chapter XXII of Mansfield Park:

“I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!” said Fanny, in reply. “… You will think me rhapsodising; but when I am out of doors, especially when I am sitting out of doors, I am very apt to get into this sort of wondering strain. One cannot fix one’s eyes on the commonest natural production without finding food for a rambling fancy.”

“To say the truth,” replied Miss Crawford, “I am something like the famous Doge at the court of Lewis XIV.; and may declare that I see no wonder in this shrubbery equal to seeing myself in it. If anybody had told me a year ago that this place would be my home, that I should be spending month after month here, as I have done, I certainly should not have believed them. I have now been here nearly five months; and, moreover, the quietest five months I ever passed.”

“Too quiet for you, I believe.”

“I should have thought so theoretically myself, but,” and her eyes brightened as she spoke, “take it all and all, I never spent so happy a summer. But then,” with a more thoughtful air and lowered voice, “there is no saying what it may lead to.”

Fanny’s heart beat quick, and she felt quite unequal to surmising or soliciting anything more.

As always with Austen much of the ethical judgement is loaded into how people ‘pass time’, much like the ‘screen time’ debate. Crawford uses nature as a mirror, as a setting in which to see herself in it. Fanny transform time into inner contemplation, feeding her imagination from the present and from memory. After all, just a little earlier she says:

“This is pretty, very pretty,” said Fanny, looking around her as they were thus sitting together one day; “every time I come into this shrubbery I am more struck with its growth and beauty. Three years ago, this was nothing but a rough hedgerow along the upper side of the field, never thought of as anything, or capable of becoming anything; and now it is converted into a walk, and it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or an ornament; and perhaps, in another three years, we may be forgetting–almost forgetting what it was before. How wonderful, how very wonderful the operations of time, and the changes of the human mind!” And following the latter train of thought, she soon afterwards added: “If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory. There seems something more speakingly incomprehensible in the powers, the failures, the inequalities of memory, than in any other of our intelligences. The memory is sometimes so retentive, so serviceable, so obedient; at others, so bewildered and so weak; and at others again, so tyrannic, so beyond control! We are, to be sure, a miracle every way; but our powers of recollecting and of forgetting do seem peculiarly past finding out.”

Miss Crawford, untouched and inattentive, had nothing to say; and Fanny, perceiving it, brought back her own mind to what she thought must interest.

Now the inattentive Crawford is clearly condemned for her poor attitude to the reflective inner patience in the front of time that comes from deeper within the self, but we would be wrong to see Fanny as the representative of unmediated time in nature. Nature for her too does not matter so much in itself and directly as for the moral reflection on its example which both mediates and co-produces its virtues. Nature illustrates that unseen activity that happens slowly and without the pressure of modernity of mind matters as much, if not more, than seen activity in the homes and towns of the fashionable, that nature is an icon of a concept as human as it is animal, vegetable or mineral – as a prompt to the moral ideas implicit in nature as it is processed by the human mind through perception, memory and hope for a better future as time passes. My own reading of it passage is somewhat cynical for no other character in Austen relies more on Fanny on letting nature have its way and in her own passage to prominence from social obscurity in the docks at Portsmouth to advantageous marriage to the son of inherited wealth (from slavery no less) and manipulated nature in a parkland landscape. No other character depends more on human ‘powers of recollecting and of forgetting’ that are part of human nature if her social passage to wealth and status is to be achieved.

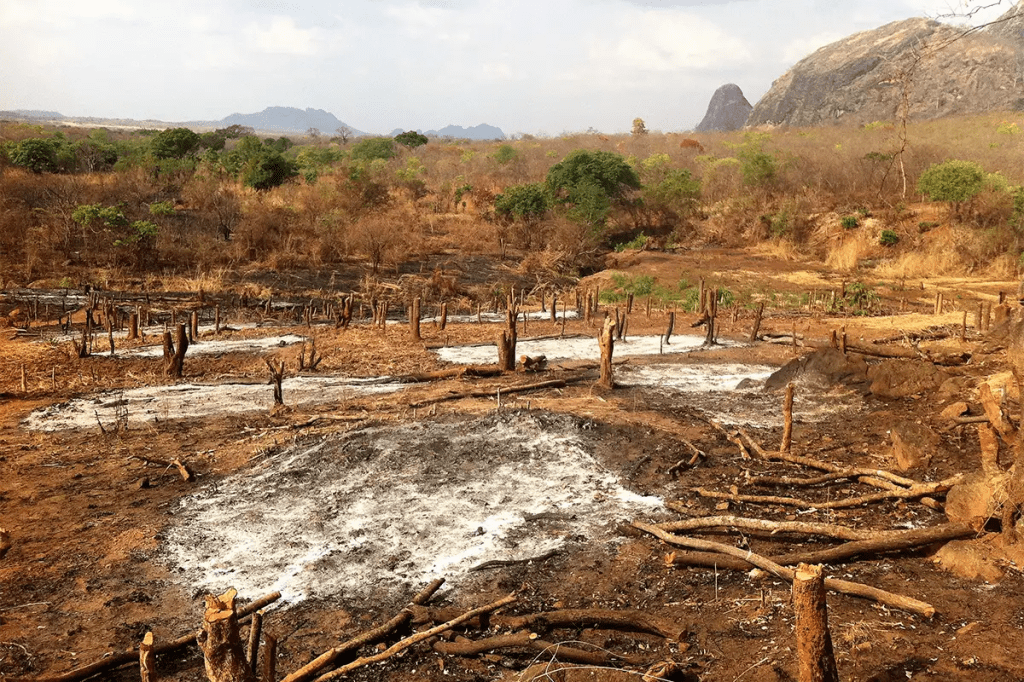

Hence I take with a pinch of salt the view that screen time is competitive with outdoors life. the advantages of the latter are a functionally mediated view of nature no less than that in Friedrich or Austen. As a medium screen time is neither bad nor good, nor opposed to nature. As so many begin to see ‘time in nature’ in running around in fashionable Lycra outfits looking good or attempting to do so in the eyes of the world, some screen time might show nature as less than a mirror of personal aggrandizement that ‘fitness’ has become and more as a resource we squander in the production of Lycra and its disposal as the wastage it becomes, as like Mary Crawford our interest flit to a place where we might look yet more stunning – an appearance in Las Vegas using tons of fossil fuel in the process.

And meantime species become extinct faster than ever has been the case and the climate becomes a threat rather than an enhancement of nature more more often – Florida is already sinking beneath such waves, taking with it (the only hope you can find in the scenario) the obscenity of Disneyland and the Trump buildings at Mare Largo.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxx