“,,. and when I love thee not, chaos is come again.” it takes ‘Othello’ to be played on a shoestring to see it as a drama of predictable personal breakdown of a man who lives only in his self-image. This is a blog on seeing Elysium Theatre play ‘Othello’ at Bishop Auckland Town Hall on Friday September at 7.30 p.m. [References To the play are from The Folger online edition: https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/othello/]

Othello is a play that lends itself to the grandiose in many ways; not least in the critical characterisation, first made by G. Wilson Knight, that there is an ‘Othello music’. That ‘music’analogy suggests the play’s main character is the chief instrument in an orchestration of grand narratives. These grand narratives tend to be ones of race, gender and an imperialist social order gone wrong in the modern world and, in an earlier more theocentric moral world, on a universal theme concerning a world fallen from God-given harmony and trust into a human version of Satanic ‘motiveless malignity’. Othello himself disdains the tendency of humans to promote ‘private and domestic quarrel’ when there are larger fish to fry and bigger roles for men to fill in the common good as he sees it: Othello enters with a simple question that becomes increasingly less simple as it is asked throughout the play: ‘OTHELLO: What is the matter here?’ (Othello, Act 2, Scene 3, 218).

... What, in a town of war Yet wild, the people’s hearts brimful of fear, To manage private and domestic quarrel, In night, and on the court and guard of safety? (Othello, Act 2, Scene 3, 227ff).

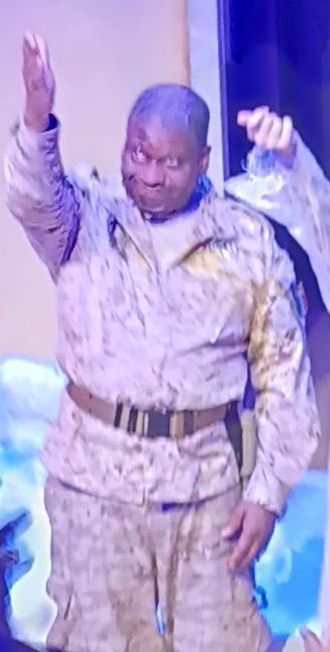

Those lines rung out to me in this play because of the beauty, calm and soothing down-played effects in the voice of Faz Singhateh, who played Othello in this tight small cast production – in a company of nine players in total. The line phrase that rings out to me in Othello – I even lectured on this when I first taught Shakespeare at the Roehampton Institute (now Roehampton University) – is ‘What’s the matter?’ (for my blog on this phrase generally in Shakespeare see this link).

It is phrase that, in the early scenes of the play is used to quell public riot and disturbance on the streets, and it is difficult to convey the power of a public leader who can perform such crowd control, when your cast of extras is limited. However, as the play progresses ‘What is the matter?’ becomes a question about what the issue is, and well as what is going on, in private spaces, like a bedroom, where the audience is presumed to be minimal because of that privacy. The ‘matter’ dealt with is often so provokingly private and domestic that it is an intra-personal rather than interpersonal matter that is evoked, even if in the latter case between only two people; a man and his wife. When Othello enters her bedroom, full of threats, her question, in being softly spoken (as it was in this production by the fabulous Hannah Ellis Ryan) is all the more unanswerable. After all, would Othello ever know what the matter is inside him, or what ‘the cause’ he boasts of fulfilling was within the seeding of his personality:

OTHELLO: ... Peace, and be still.

DESDEMONA : I will so. What’s the matter?

(Othello, Act 5, Scene 2, 55f).

Othello always, even now, sees the problem (‘the matter’) that is at stake lies in some one else’s inner life not his. When he allows Emilia to enter the room, thinking his wife fully dead – she isn’t – it is her who represents the problem and is asked to explain herself, just as it always been the fault of others who disturb social order in Othello’s mind. He asks the question, in its most offensive form: ‘What’s the matter with thee now?’ (Othello, Act 5, Scene 2, 130) In Elysium Theatre’s production, this use of the simplest exhange in theatre indicates areas of the profoundly unanswerable question- what is it that lies within me? what is it inside me that disturbs me? It all came across with immense power.

There is no denying that this company acts on a shoestring, as I have implied in a reviews of another show I have seen of theirs – a blog is linked to that play’s name: Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (where Hannah Ellis-Ryan again triumphed, here as Nora) and Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. However, in Othello, the shoestring is so short it must be done for a reason.The only meaning of the sets is their inadequacy.

Even as the facia of homes they matter more for the cracks seen so visibly painted down them and the exposed brick walls – anachronistic for Venetian architecture – and the sense of something that has tried to look, but has failed, more impressive than it ever will be or has been. This sense of something in ruins, such that the pretensions its facia are made manifest, is very much the feel of this play and this production. This is so wheher we focus on the treatment of the bragadoccio of the Venetian Republuc and its Empire, the capitalist imperial adventurer culture par excellence of its period, or the model of the ‘noble man’ to which Othello, late a military mercenary, aspires.

Stage properties were minimal, often anachronistic (folding plastic chairs for instance), only impressing when the bed is introduced on which sex-gendered murder occurs and which has a concealed sharp weapon under its mattress – put there before Desdemona went to bed in it. It is the most impressive weapon in the play, or so Othello inappropriately boasts to Gratiano as the latter rather unnecessarily, given the presence of a corpse, asks again: ‘What’s the matter?’:

GRATIANO, ⟨within⟩ If thou attempt it, it will cost thee dear; Thou hast no weapon and perforce must suffer. OTHELLO Look in upon me, then, and speak with me, Or naked as I am I will assault thee. ⌜Enter Gratiano.⌝ GRATIANO What is the matter? OTHELLO Behold, I have a weapon. A better never did itself sustain Upon a soldier’s thigh. I have seen the day That with this little arm and this good sword I have made my way through more impediments Than twenty times your stop. But—O vain boast!— Who can control his fate? ’Tis not so now. Be not afraid, though you do see me weaponed. (Othello, Act 5, Scene 2, 305ff).

Men who boast the size of their weapon and threaten ‘naked assault’ on other men rarely draw attention to the fact that theircweapon is just like those, in the end, any soldier is ‘sustaining’ on his thigh. Even in extremis Othello resorts to boyish boasts about the size and quality of his unseen instrument. And that this is an answer to the perennial question of ‘What’s the matter?‘ is even more telling. For me this production had a better Othello even than acknowledged and better known great actors (excluding Olivier who was just embarrassing).

Faz Singhateh as Othello was for me magnificent both for the down-playing of Othello’s fabulously easily attained command of the stage and the Venetian state at home or abroad. He does this with the softest of voices and the broken-down, irrational and violent rage of his actions and speech when he is played as insane and brought to fits of epilepsy or in publicly disgraceful show as a bully and wife-beater. He strikes his wife in front of dignitaries. His speech is made up of inarticulate memories of Iago’s vile metaphors for the sexual license that the ancient says is rife in Venice:

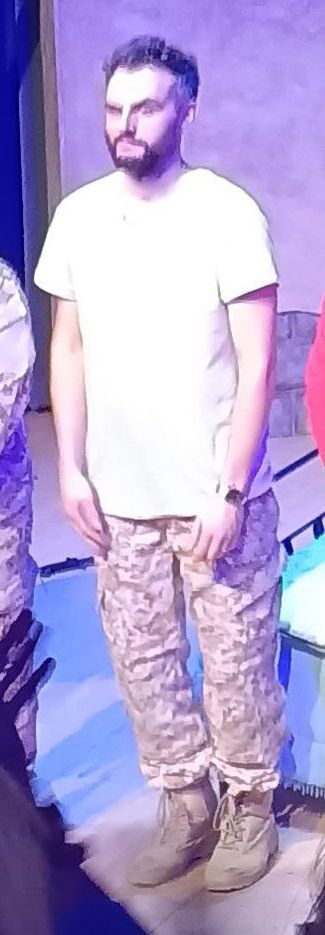

I will linger for the moment at the brilliance of Singateh’s ‘over-the top’ rants in his sexually motivated insanity for there was much debate about this amongst our party: with half of it thinking an example of a good actor overacting when it came to passion and the others (me and Linda) thinking it a fine show of just what the deregulation of all proportion does to behavioural performance. There is no regulation in such moments – hence the inability to discover ‘what’s the matter’ for most of us in disorder and hence our resentment (unfair of course but the deregulated is unfair, unequal and with the potential to chaos) of those who feel the matyer within us can be simply stated or articulated. Iago has the poison that helps here, and when well acted, as this Iago was by Danny Solomon, we begin to guess that Iago too speaks of things so over-determined that he too cannot guess the cause or untangle one cause from many in play inside him. His regulation though contains his disorder where Othello’s does not; organised more like that disturbance psychiatrists label psychosis rather than neurosis.

Iago thinks he understands the world he uses to bring Othello’s insane neurosis to the surface. He points out in Act 3 Scene 3 that, though underneath Venetian society people have the ethics of ‘animals’ (as he sees animals anyway) in every respect, the actions these values foster is played out in a manner that conceals the intensity of sexual sensation that might be desired but dare not be enacted on that public stage.

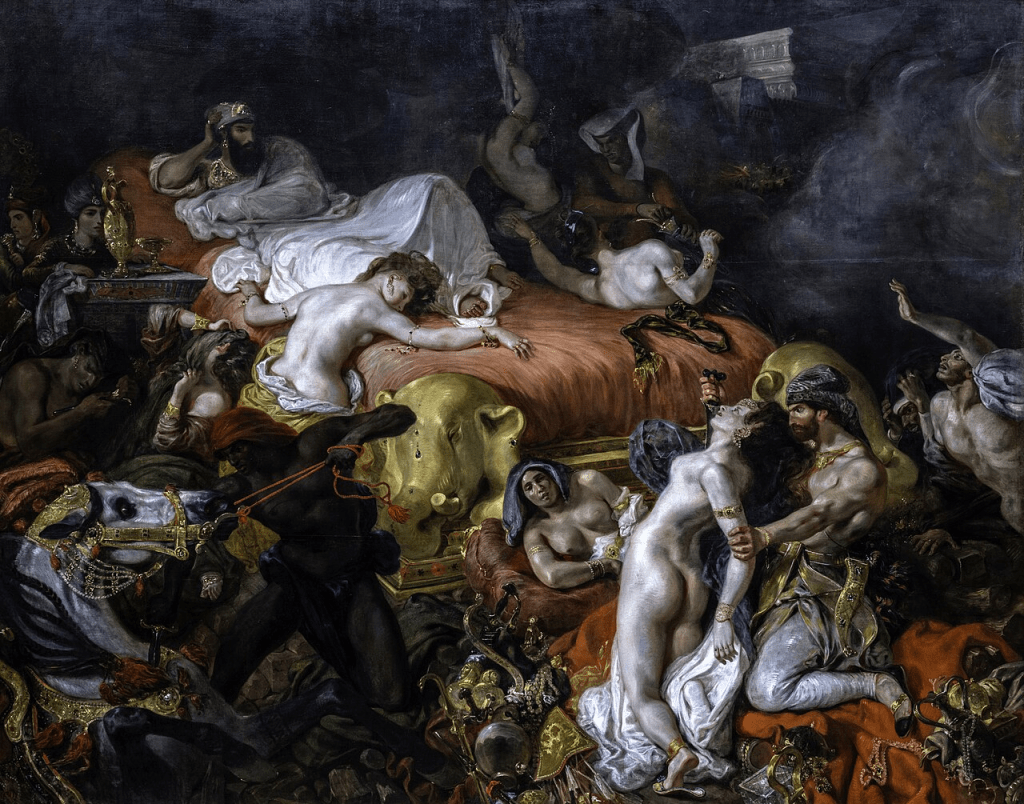

I might have been reading the Shakespearean verse cited below, so clearly was I able from just hearing to see how the visual is conjured by Iago in his discourse of the denial of the social underworld’s access to the sight of others in the fine acting of Solomons. He plays an Iago so riven by the nastiness of his imagined scenarios that seem to derive, like those of Delacroix’s Sardanapalus, from what we guess is truly an impotence so profound it hates all other actors, in both senses of that word, in this world.

Death of Sardanapalus by Eugène Delacroix

It is impossible you should see this, Were they as prime as goats, as hot as monkeys, As salt as wolves in pride, and fools as gross As ignorance made drunk. But yet I say, If imputation and strong circumstances Which lead directly to the door of truth 465 Will give you satisfaction, you might have ’t. (Othello, Act 3 Scene 3, 459ff).

An impossible sight is manifested here by virtue of the wish to see what it is impossible to see because it is denied to to our ken. For the first time in a production I have felt the dynamic link of the regulated psychotic hatred of this verse with Othello’s version, a deeply neurotic one, in the next act:

OTHELLO What would you with her, sir? LODOVICO Who, I, my lord? OTHELLO Ay, you did wish that I would make her turn. Sir, she can turn, and turn, and yet go on, And turn again. And she can weep, sir, weep. And she’s obedient, as you say, obedient. Very obedient.—Proceed you in your tears.— Concerning this, sir—O, well-painted passion!— I am commanded home.—Get you away. I’ll send for you anon.—Sir, I obey the mandate And will return to Venice.—Hence, avaunt! ⌜Desdemona exits.⌝ Cassio shall have my place. And, sir, tonight I do entreat that we may sup together. You are welcome, sir, to Cyprus. Goats and monkeys! (Othello, Act 4 Scene 1, 284ff).

Othello’s ‘Goats and Monkeys‘ erupts out of this attempt to play the civil man of the Venetian court when he is at his most disturbed, but yet the ‘matter’ of his disturbance unspeakable. Every word is an overdone sexual pun for Othello like that on ‘turn’ and the ‘do’ and ‘have my place’. Every act of social performance is perpetually capable of being one of sexual performance. And I saw this in the foaming version of Othello in Singhateh’s singular performance. His performance seems to have come from having visited the very Hell in which Othello’s personality has been moulded from the experience of racism, antagonistic and supposedly benign, in the model of Venetian civility in which to cast himself which is, in the end no more than a facade, or facia, as rotten as those signified in the play’s bare sets.

Excellent wretch! Perdition catch my soul

But I do love thee! And when I love thee not,

Chaos is come again.

(Othello, Act 3 Scene 3, 100ff).

Cassio is never uncovered as the dangerous dolt that he is, except by Iago’s false ruse with him. However, behind him, in this production and the text I think, is little more than a raw boy, unable to take his drink but still doing so at the slightest provocation. A boy who is sexually profligate and cruel to the women he abuses by gaining their trust, like Bianca whilst intent on betraying it. He is most of the time no more than a buffoon in this production and brilliantly played as such by, I think (for most actors are not named) by one of Alexander Towson, Jamie Brown, Robin Kingsland, or Stewart Sylan-Campbell. Yet this is the ‘man’ that Venice leaves in Cyprus to represent its public face, riddled through with class prejudice and toxic masculinity, who abuses women by persuading them he might marry them with no intention towatds them than for raw sex, that will be enjoyed in the retelling of it more whilst he lies boasting in a common bed with his male military peers than in the event. That common male bed by the way is integral to the plot. It is where, Iago claims he overhears Cassio’s talking dreams about Desdemona and how he leaves her handkerchief for Cassio to find and for Othello to ‘see’ as evidence of his wife’s sexual freedom with other men.

I suppose my theme here is that the attempt to find universal principle on a grand scale in what is in fact diminutive and inadequate if looked at properly, as Emilia I think does, is the human flaw the play exposes, of which the importance in it of one handkerchief is a kind of symbol. That item is indicative of smaller domestic issues somehow, by some grand principle of the human need to inflate our significance as human beings grow too large to be contained. Take Emilia’s assessment of the handkerchief plot, in which she sees only the vanity of dull and foolish men – whether they be high-ranking like Othello or more lowly like her husband, they see more than what belongs ‘to such a trifle’ in it:

O thou dull Moor, that handkerchief thou speak’st of I found by fortune, and did give my husband— For often, with a solemn earnestness (More than indeed belonged to such a trifle), He begged of me to steal ’t. ... (Othello, Act 5 Scene 2, 268ff).

Faz Singhateh sees this I think as the key to the soul of his Othello and the result is an Othello far more consumingly tragic in nature than I have ever seen, even if not the very best. His Othello is as mild in his appearance, tone and audible volume of his speech as can be managed in a theatre and still be heard – he enunciates the verse as if a pupil of Cicely Berry, so clearly and beautifully. It never goes over the top until his outer facade – that which people call gentle and noble, by the class standards of Venice – fails him entirely and he sees Venetian civility for what it may be – only a sham facade but cracked on the surface and with poor brickwork underneath. He never learns that however, for he only has that facade available to him as a model to imitate as an entrant to Christian society. Take his last speech, for instance, though what I say here has been said oft before:

Soft you. A word or two before you go. I have done the state some service, and they know ’t. No more of that. I pray you in your letters, When you shall these unlucky deeds relate, Speak of me as I am. Nothing extenuate, Nor set down aught in malice. Then must you speak Of one that loved not wisely, but too well; Of one not easily jealous, but being wrought, Perplexed in the extreme; of one whose hand, Like the base Judean, threw a pearl away Richer than all his tribe; of one whose subdued eyes, (line 408) Albeit unused to the melting mood, Drops tears as fast as the Arabian trees Their medicinable gum. (Othello, Act 5 Scene 2, 398ff).

The tone of the verse returns to the authoritative ‘softness’ that Singhateh adopted in the early play – the voice of a man who should not need shout or speak harshly to be heard and obeyed. It is a mix of the gentle as an ethical and a class-based tone, like the meaning of the word itself. It uses common rhetorical devices of false modesty as well as rich imagery and sound effects that are as mellifluous as the images are of honey-like fluids, such as the alliteration and assonance in lines 408 – 411 and a pace through them set by long stressed vowels. But it is all a facade.

To call these events ‘unlucky’, or his jealousy being ‘not easily’ stimulated are attempts to cover behaviours we have seen ourselves earlier in the play and refuse to see covered over again by civility and false gentleness. The cover is musical and magical, like the ‘medicinable gum’ it evokes, but it is never more than gum. If this is ‘loving too well’, let all of us be loved in a way that is just enough and no more and escape murder or abandonment. And I think all this explicates Othello’s internalised racism too. Just as he resorts to stereotypes of Jews (the ‘base Judaean’ is so greedy he fails to satisfy his greed for that reason) so my heart tore when this Othello made his ‘Haply that I am black’ speech.

... Haply, for I am black And have not those soft parts of conversation That chamberers have, or for I am declined Into the vale of years—yet that’s not much— She’s gone, I am abused, and my relief Must be to loathe her. O curse of marriage, That we can call these delicate creatures ours And not their appetites! I had rather be a toad And live upon the vapor of a dungeon Than keep a corner in the thing I love For others’ uses. Yet ’tis the plague ⟨of⟩ great ones; Prerogatived are they less than the base. ’Tis destiny unshunnable, like death. Even then this forkèd plague is fated to us When we do quicken. (Othello, Act 3 Scene 3, 304ff).

Here it is. Soft speech that pretends not to be so, yet using every rhetorical trick of the Venetian, or English (come to that), nobleman, that spends time imagining the degradation of the ‘base’ to better emphasise his own status amongst ‘great ones’. He uses his Blackness as a deficit however that he cannot countermand (in the way he so easily shuffles off the fact of his older age as ‘yet that’s not much’), a ‘base’ characteristic that he will not ever deny, though setting himself singly above the common man of Black skin. Being Black will allow him to ‘loathe’ that which he cannot have, and thence not have as the kind of love that is the reward of the great ones. The whole issue with Othello is that he speaks like a white nobleman such that it forms a thing of substance over his face that Fanon would call a ‘white mask’.

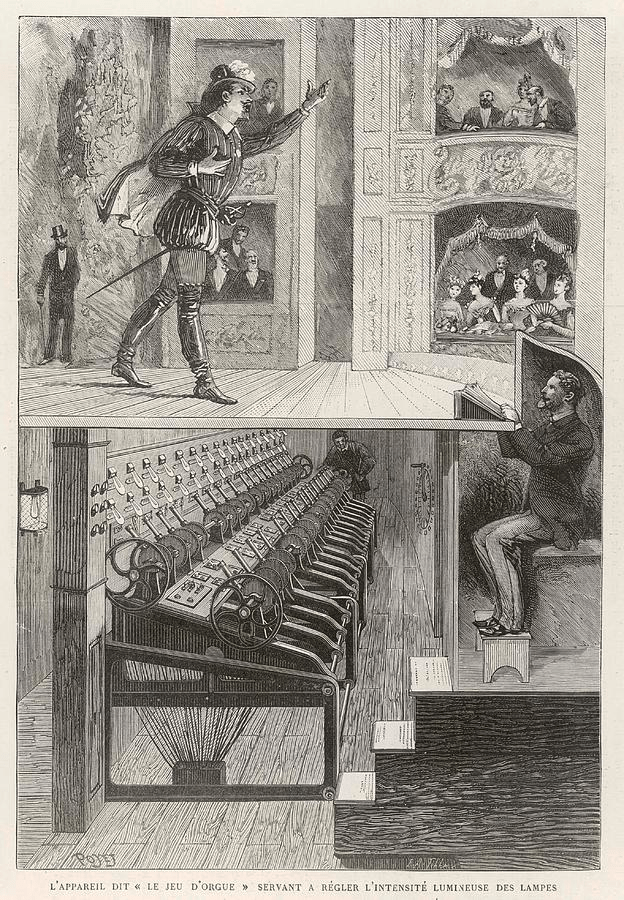

Othello is after all an actor, and when that does not mean being in military action, it means talking like a man who plays his role without need of direction as in one of my favourite lines from the play:

OTHELLO Hold your hands,

Both you of my inclining and the rest.

Were it my cue to fight, I should have known it

Without a prompter.

(Othello, Act 1 Scene 2, 101ff).

The prompter in the nineteenth-century French theatre.

But let me return to my title, for these lines haunted me before I got to the theatre such that it made Singhateh’s performance of them even more delicious to my ear and imagination:

Leaving aside the complex way in which to him Desdemona is both excellent and a wretch, for these are paradoxical, what hummed in my head was what Othello could mean by his protestations of love. They are not straightforward words. Othello, and not for the only time, is consigning his soul to damnation, to be lost in ‘perdition’ (a loss in itself) almost as Dr. Faustus does for Helen with Mephistopheles:

FAUSTUS.One thing, good servant, let me crave of thee,

To glut the longing of my heart's desire,—

That I might have unto my paramour

That heavenly Helen which I saw of late,

Whose sweet embracings may extinguish clean

These thoughts that do dissuade me from my vow,

And keep mine oath I made to Lucifer.

(Christopher Marlowe, Dr Faustus, Scene 12, 79ff

see https://www.owleyes.org/text/faustus/read/scene-12#root-74455-3-3).

But what does the word ‘but’ do to the sense of Othello’s speech. Does he say ‘Let me be damned because I would still love you, Desdemona’ or ‘I would be damned but for loving you, Desdemona’: in which latter case the speech when taken with the next part (‘when I love thee not, chaos is come again’) is a rhetorical chiasmus. in which two things are said which are not identical but mean the same thing. To me the little speech is very indicative of Othello’s deepest self-awareness.

At this point, Othello is highly dependent on Desdemona for he has seen that his life before his marriage was a kind of Hell already; either like the chaos before the world was formed or Hell as the antithesis of the divine order (of heaven), for which the Venetian Republic and its Empire of trade supported by militias is only a poor secondary facade. In that he is perhaps even more like Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus – a foolish shallow man who believes in his own self-image just as the society that validates him believes in him. They do so because he represents their self-image, whilst, at least, he is of ‘service’ to the state.

Sexual jealousy dips Othello back into the order of the animal, rather than human, world with which so many Venetians characterise Othello. When Iago wants to really frighten Brabantio about the safety of his daughter, he says, tying the concept of perdition to the chaotic in the social order:

... You have lost half your soul. Even now, now, very now, an old black ram Is tupping your white ewe. (Othello, Act 1 Scene 1, 96ff).

This is the kind of poison that uses how the sexual might cross the boundaries that Iago’s plan works with, exposing Othello to see that to which he prefers to be blind – his actual vulnerability to a state that values him only as long as he is of service and will displace him when it reaches that point and take away from hom all that made him vsluable to himself..

I think this production and the acting in it magnificent, and this despite the fact that I missed so much of the first half because a lady on the row behind had what seemed a mini-stroke during the performance. The lovely lady had to be helped out whilst the actors continued on stage. She was alright I was told afterwards but it is a testimony to the play that it could be rescued from such disturbance and distraction. The play continues at these venues : do see it!

Tue 8 Oct Princess Alexandra Auditorium, Yarm

Wed 9 Oct Carriage Works Theatre, Leeds

Thurs 10 Oct Georgian Theatre Royal, Richmond

Fri 11 Oct Theatre 41, York

Sat 12 Oct Empire Theatre, Consett

Tue 15 Oct Seventeen Nineteen Theatre, Sunderland

Wed 16 Oct Assembly Rooms, Durham (DURHAM SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL)

Thurs 17 Oct Assembly Rooms, Durham (DURHAM SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL)

Fri 18 Oct Assembly Rooms, Durham (DURHAM SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL)

Sat 19 Oct Assembly Rooms, Durham (DURHAM SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL)

Sun 20 Oct The Maltings, Berwick

Note: Cast members other than the principals are: Heather Carroll, Alexander Towson, Jamie Brown, Robin Kingsland, Luce Walker, and Stewart Sylan-Campbell.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx