Finding the expression you want of the ‘wonder at sheer being’ when the man you love comes to bed in his ‘pijamas de ciervos‘. Reflecting on a moment from Garth Greenwell’s (2024) Small Rain.

In the picture above various retailers appropriate expressions of joy in a young man in order to sell deer pyjamas, or as Garth Greenwell names that garment (whether in one or two pieces) when worn by his Portuguese-with-Spanish-also-as- a-first-language speaking lover, L, pijamas de ciervos. It is a beautiful moment, that resounds oddly, as does so far the whole book Small Rain, as I read on. Although it follows the method and wonderful writing style of the early novels it seems so different in tone – capturing what is human in persons at a much more resigned, even stoic, level of their being and his capacity to know their being, or in fancier terms its metaphysical ontology and epistemology.

Small Rain I will write about later, at which point I will collage tbe look of the book sitting within the disturbingly lovely cover of the British hard copy, with its beautifully adapted version of Hockney’s Rain (1973) on it, when I have finished reading it. It will also be WHEN I have the time and the emotional capacity, for it is a read that makes demands on you at many levels.

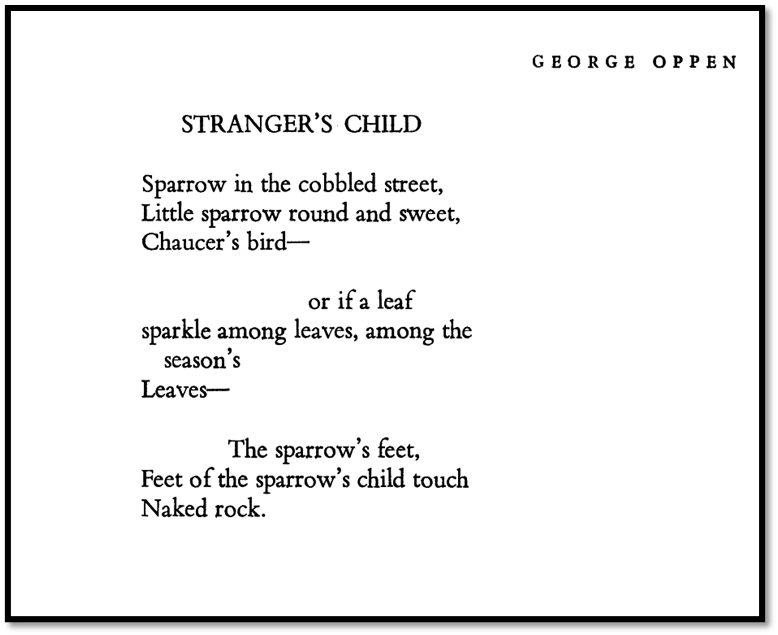

However, last night in bed with a torrential downpour resounding outside I read this poem from the opening of Section IV of that gorgeous book, wherein the ill narrator – who probably is and is not Greenwell himself – sits in a hospital bed unable to read novels but managing single poems, ones he knows and has taught to learners; both reading and looking at the ‘shape of the words on the page’ of a poem. It was a poem by a poet that I didn’t know, so selective is my transatlantic knowledge of writing in English, George Oppen’s Stranger’s Child. (page 178-179 in (1))

Greenwell, in a moment peculiar to a memoir of an an episode from a life of which this is an auto-fictional version, absorbs that poem and its look into the moment conveyed and the memorial associations, of his past and the past of his world as informed (formed within I mean) by reading and reflective moments of critical self-awareness. He considers the poem in terms of what he liked about it, and how he related it to the world he knows. As I thought about this beautiful moment, of course, I reflected on how this book deflects from the trajectory I thought to be established in Greenwell’s work as a storyteller of the queer as queerness intersects with psychosocial, psycho-cultural and political aspects of the Western world.

There are obvious reasons for the difference of this book from earlier ones that it itself reflects upon, but not in an attempt to categorise that difference: the fact of ageing, the fact of return to a native place, the awareness of changes in the interaction between self and place, and the confrontation with the certainty of one’s mortality, if not of the duration of its persistence.

And the choice of Oppen is not I think accidental for he stands it appears, from the evidence of my thin preliminary reading provoked by Garth, at a cusp in history in which American identity defines itself in terms of the responsibility of the writer to what is, what might be and, in a more normative ethical insistence, what should be. And I read this morning a beautiful essay by Oppen, The Mind’s Own Place, which, the Poetry Foundation helpfully comments, takes its title from Milton’s Satan: (2)

Hail horrors, hail

Infernal world, and thou, profoundest Hell,

Receive thy new possessor: one who brings

A mind not to be changed by place of time.

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a Heaven of Hell, a Hell of Heaven. (3)

As you read on, with the help of the notes which I reproduce as my own ( as notes 4 – 8 respectively – 14 – 18 in the digital text), it is clear Oppen often appropriates quotations from others to interpret purely as they suit his own purposes and argument including his major reference here to a poem by Bertolt Brecht. He uses quotation freely to define an area not truly that referenced in the text he is quoting. And this is true of the words of Milton’s Satan too, who Oppen uses as his base to assert that poetry guides the mind as the interpreter of how the senses, emotions and thoughts deal with the problem of perceiving the world as it is.

Heaven and Hell here may for Oppen be political issues strung out on the scale to those he references in my quotation below, the left of politics looking for a better world, in Brecht, and the right, in their own version of Hitler’s self-image. The mind has a duty that stands outside place, even if that place is ‘Heaven’ or if it ‘Hell’. It can spend its energies making ITSELF a replica of heaven or hell or it can recognize that:

…the definition of the good life is necessarily an aesthetic definition, and the mere fact of democracy has not formulated it, nor, if it is achieved, will the mere fact of an extension of democracy, though I do not mean of course that restriction would do better. Suffering can be recognized; to argue its definition is an evasion, a contemptible thing. But the good life, the thing wanted for itself, the aesthetic, will be defined outside of anybody’s politics, or defined wrongly. (see (2))

Oppen argues, I think, that there is a moment where the perception of the aesthetic – what beauty (and he included happiness in that) is – is independent of our concern and responsibility for the whole community to eradicate, or at least mitigate, social and individual suffering and make to bloom, or help towards that end, an age of psychosocial justice and love. Greenwell helps put this into context amid his narrator’s reflection in his hospital bed – his sight diminished and his hope uncertain, but still reflecting:

Maybe it helps to know more about Oppen, not that I know very much: the career-long worrying over the relationship between the one and the many. the communal claim of politics – he was a communist, he and his wife, Mary, they were hounded out of the country after the war and spent years in Mexico – the communal claims of politics and the individualizing claims of poems. (page 179, see (1))

What an odd thing to find in art I thought – but how shallow that immediate thought of mine! If I think of how I read his wonderful debut What Belongs to You and his great second novel Cleanness (see my blog on the latter as a link here), I think of the intensity of joy I find in that a mind so much speaking out of a tradition and yet making it new seems to find place to articulate a complex intersectional queer politics that is communal whilat not disrespecting the body of the individual as well as the social body. That is. perhaps, another way of saying that is a ‘worrying over the relationship between the one and the many’, the latter asserting itself in Pride politics and a prompting belief in communalism, if not communism.

And Oppen looks at that head-on in his essay, of which I place an excerpt here. For the Peace Marches of Oppen’s time replace the Pride and social justice and peace marches of ours.

The people … in the Peace Marches are the sane people of the country. But it is not a way of life, or should not be. It is a terrifying necessity. Bertolt Brecht once wrote that there are times when it can be almost a crime to write of trees. I happen to think that the statement is valid as he meant it.(4) There are situations which cannot honorably be met by art, and surely no one need fiddle precisely at the moment that the house next door is burning. If one goes on to imagine a direct call for help, then surely to refuse it would be a kind of treason to one’s neighbors. Or so I think. But the bad fiddling could hardly help, and similarly the question can only be whether one intends, at a given time, to write poetry or not.(5)

It happens, though, that Brecht’s statement cannot be taken literally. There is no crisis in which political poets and orators may not speak of trees, though it is more common for them, in this symbolic usage, to speak of “flowers.” “We want bread and roses”: “Let a thousand flowers bloom” on the left: on the right, the photograph once famous in Germany of Handsome Adolph sniffing the rose. (6) Flowers stand for simple and undefined human happiness and are frequently mentioned in all political circles. The actually forbidden word Brecht, of course, could not write. It would be something like aesthetic. But the definition of the good life is necessarily an aesthetic definition, and the mere fact of democracy has not formulated it, nor, if it is achieved, will the mere fact of an extension of democracy, though I do not mean of course that restriction would do better. Suffering can be recognized; to argue its definition is an evasion, a contemptible thing. But the good life, the thing wanted for itself, the aesthetic, will be defined outside of anybody’s politics, or defined wrongly. William Stafford ends a poem titled “Vocation” (he is speaking of the poet’s vocation) with the line: “Your job is to find what the world is trying to be.”(7) And though it may be presumptuous in a man elected to nothing at all, the poet does undertake just about that, certainly nothing less, and the younger poets’ judgment of society is, in the words of Robert Duncan, “I mean, of course, that happiness itself is a forest in which we are bewildered, turn wild, or dwell like Robin Hood, outlawed and at home.”(8)

I find those two sentences about the assertion of a just politics electrifying: ‘But it is not a way of life, or should not be. It is a terrifying necessity’. They electrify for I can begin to see how this novel, for surely Small Rain is that, puts art back into the search for a way through ‘a forest in which we are bewildered, turn wild, or dwell like Robin Hood, outlawed and at home’. We need to dwell somewhere and even outlaws need a home in the beautiful that sustains and that may be art, and which is not political nor apolitical but asserts the need to act, write and reflect in the parameters of a ‘definition of the good life’. Where do I take this reflection? What do you think?

Except it’s good to see the expression of a good life in your loved ones’ ‘deer pyjamas’. And, at the same time, there is that in true perception that, even of pure beauty which Greenwell’s narrator analyses but also applies to himself in a telling moment, wherein thoughts, sense and feelings, which touch each other, also each and all together touch in the end something cold and unrelenting and less giving than ‘cobbled streets’: ‘Naked rock’.(page 188, see (1)), The brilliance of the writing by Greenwell here shocks me – AGAIN! And makes me love him more.

With love

Steven

____________________________________________________________________________

(1) Garth Greenwell (2024) Small Rain London & Dublin, Picador.

(2) George Oppen ‘The Mind’s Own Place’ available in full with introduction and notes at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69407/the-minds-own-place

(3) From John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book 1, 229ff.

(*) Notes 4 – 8 are exact transcription from the text referenced at (2) above.

(4) From Brecht’s poem “To Those Born Later” (“An Die Nachgeborenen”): “What kind of times are they, when / A talk about trees is almost a crime / Because it implies silence about so many horrors?” See Bertolt Brecht Poems, 1913-1956, ed. John Willett and Ralph Manheim (New York: Methuen, 1976), 318.

(5) Also in the Hatlen/Mandel interview, in response to a question regarding his return to the writing of poetry, Oppen says: “Rome had recently burned, so there was no reason not to fiddle”(MP 34).

(6) “We want bread and roses” is a slogan associated with a textile strike that took place in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912. “Let a thousand flowers bloom” is a misquotation of Mao’s 1957 slogan “Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend.”

(7) In William Stafford, Stories That Could Be True: New and Collected Poems (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), 107. Incidentally, the line appears in the poem as a quotation of the speaker’s father’s advice.

(8) Robert Duncan (1919-88). The quotation is from an unknown source.

One thought on “Finding the expression you want of the ‘wonder at sheer being’ when the man you love comes to bed in his ‘pijamas de ciervos’. Reflecting on a moment from Garth Greenwell’s (2024) ‘Small Rain’.”