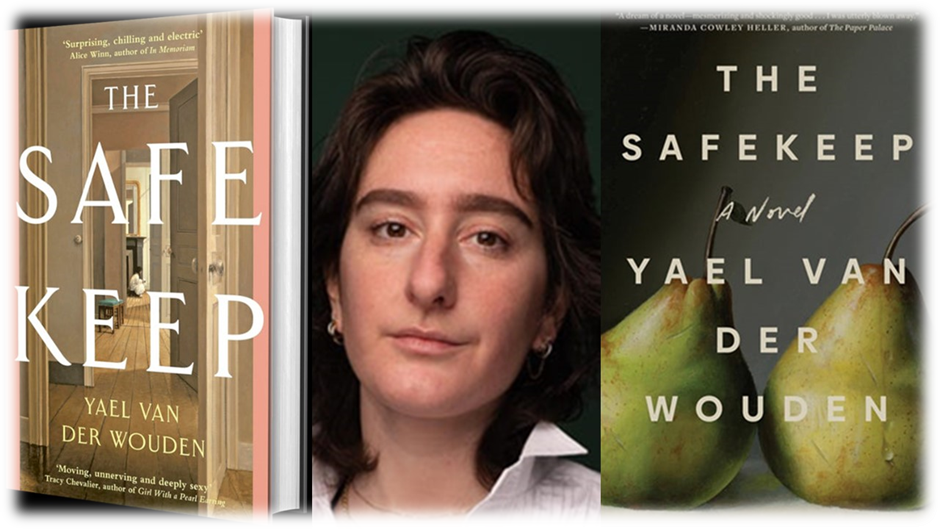

CONTAINS SPOILERS! “…, what’s the point of having good things if you can’t touch them?” And Isabel would answer: “They are not for touching. They are for keeping.”[1] The Safekeep is well titled since it is a book about why we attempt to guard from others those things we find most precious, keeping them locked from the touch of strangers. This is a blog on Yael Van Der Wouden (2024) The Safekeep: A Novel, Viking. CONTAINS SPOILERS!

The term nearest to ‘safekeep’ for our modern ears is ‘safeguarding’, a thing done (supposedly) to save the vulnerable from abuse, but with an implied belief that we hold the lives of the safeguarded precious. Safeguarding is a behaviour in the novel and is applied to many things, from rare Dutch china plate, silver utensils, or one’s sexual virginity. Likewise, the things we use to safeguard, nominally called safeguards (or safekeeps), exist in the novel, too, such as vitrines for holding china or the stated ethics of self-protection in our psychological defences.

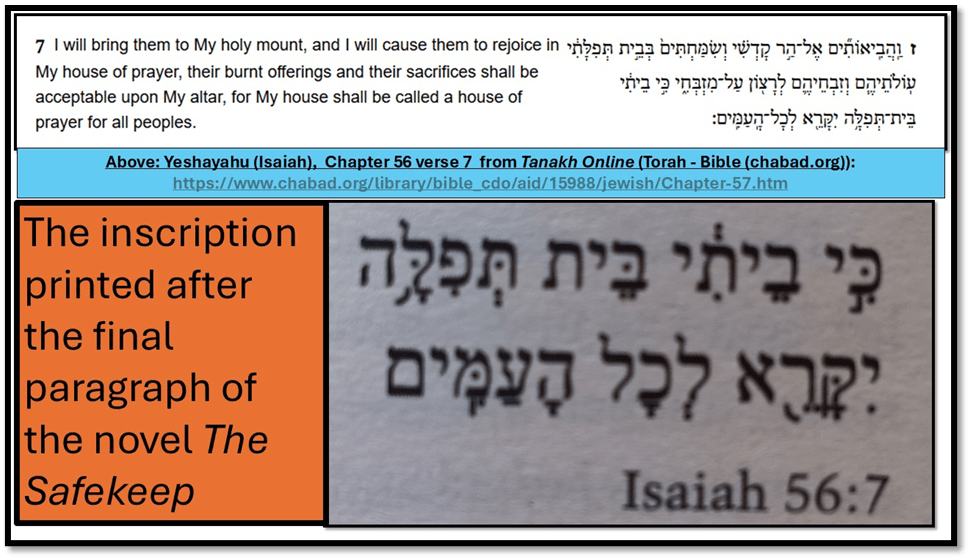

And yet, though perhaps they exist, I have found no critiques of Yael Van Der Wouden’s beautiful novel of the complex path to love between two women that really referencs its title: The Safekeep or any synonym thereof. And this is despite the novel making bold attempts throughout to reference what safekeeping may be as an action and what are the things we aim to keep safe from others’ misuse of them. Indeed, the novel ends with a quotation (admittedly printed only in Hebrew (except for the chapter and verse reference) of a part of the Book of Isaiah (or Yeshayahu in transliterated Hebrew).[2] In full translations of the Hebrew of that chapter we are told that the truth of the Jewish Temple of Yahweh must be guarded at first, and until the New Revelation of God by the Messiah. To sfegyard we must hold back that which is considered foreign or alien and perhaps unclean or unsafe, such as the ‘sons of foreigners’ spoken of in verse 6 and named by the pronoun ‘they’ in verse 7.

Chapter 56 is a chapter in which the prophet urges the Jewish faithful to keepsafe or safeguard the Jewish faith and stand against its degradation, whilst they await the Messiah (the prophet of a renewed covenant to replace the Mosaic one).[3] Yet Verse 7 is also a special verse, beloved of those Christians who see it as the God’s predictive message proclaiming his Messiah, opening God’s gift of grace to Gentiles, the Christian interpretation of the phrase, ‘the sons of foreigners’ in verse 6, that is those not of the Jewish faith who will become full Christians.

Van der Wouden uses the inscription from Isaiah 56:7 as an analogy, although perhaps an ironic and deeply nuanced one, of the Gentile Isabel being offered the ‘gift’ of her love by Eva for the restoration of justice (somewhat belatedly and with conditions) in which a Jewish family’s house (if not necessarily one of prayer) is offered back on the condition of the redemption of the Gentiles who once stole it. The new dispensation that cements the love of Isabel and Eva (an Eve without an Adam) is complicated and people will think differently about its justice but it has everything to do, in however a complicated way, with people who feel kept and safe in each other.

At the end what binds the woman is a touch: ‘Eva’s touch was a soft one’. It may be soft but it declares something deeply guarding and keeping, protection: ‘I’m here, it said, don’t startle’.[4] And even if we fail to read through this a new testament of love offering itself as both open to our touch and yet protective, we ought perhaps to see the difference here between the Isabel we meet on the first page of the novel, who introduces us first to a possible antinomy between the words ‘touch’ (which predicates possible damage through use) and ‘keep’ and is the quotation I excerpt in my title, wherein younger brother Hendrik teases his staid sister for not using the best of the family china kept safe in a vitrine. Isabel has found a fragment of broken plate in the roots of a gourd in her garden, but knows that no plate of this description has ever been broken by her family throughout the history of them as known to her:

It had once been a plate, which was part of a set – her mother’s favourite – … When mother was alive the set was kept in a glass vitrine in the dining room and no one was allowed to handle it. It had been years since her passing and the plates were still kept behind closed doors, unused. On the rare occasion when Isabel’s brothers visited, Isabel would set the table using everyday plates and Hendrik would try to pry open the vitrine and say, “Isa, Isa, come now, what’s the point of having good things if you can’t touch them?” And Isabel would answer: “They are not for touching. They are for keeping.”[5]

A Dutch vitrine

We barely notice the chiming of the word ‘kept’ through that passage but it is there. People without respect for the safeguard like the young Hendrik, a boy who does not obey sanctions that make certain things ‘untouchable’ (like that against schoolboys who wish to touch the body of their older male piano teacher), will, given a chance, try to pry open locked safekeeps. Here it is only a glass vitrine here that is pried open but the intention, Isa knows, is to ‘touch’ pieces whose care is in the hands of her in the role of a stern keeper or curator. Hence, the antinomy – if we need to ‘keep’ things as they are, they should not feel a ‘touch’ upon them.

Nearer the end of the novel the semantics of the verb ‘to keep’ are indeed central to a debate between Isa and her aunt, Tante Rian, regarding an oven dish that Rian is ‘keeping’ for a neighbour but has not yet given back despite the fact she has been asked about it by that neighbour, after the latter’s absence of ‘many years’ (perhaps in a concentration camp):

Isabel started, “ So she _” Then stopped. Then asked, “She gave you that dish, you said?”

…

Rian didn’t seem to understand the question. “What?” she said. “Gave, gave it, she gave it me to keep.”

“To keep.” …”where did she go that you had to keep it?”

Rian looked at her now, Looked up with watery eyes. … “Go!” she said. “Where did anyone go, Isabel. It was war, … People left, people came, people ran away or hid away, I don’t know. … But I kept that dish for her, you know. … She wasn’t here and I kept it for her.

“So was it a gift?” Isabel asked. “or were you keeping it?”

Rian turned away from her. … “you’re playing with words now. What does it matter, gifting, keeping? … “Oh, I don’t want to talk about it!”[6]

Mid nineteenth-century Dutch oven dish

It matters here what ‘keeping’ means, where the usual meanings of curation or preserving, on the one hand, and taking permanent possession, on the other are both possible in the word ‘keep’, just as ‘giving’ of a thing from one to another has to be distinguished from ‘stealing’ or ‘theft’, an accusation that flies around the novel too. It does so in Isa’s suspicions of her maid, Neelke, or of Eva, before at least Eva becomes the beloved and, in the end, ‘gifts’ herself to Isa. In Eva’s diary account, she tells a story told in the concentration camps, using the meaning of ‘safekeeping’ as meaning curation or safeguarding:

Malcha told me she knew a woman who came back from the camps and then went to the family who were safekeeping her things. They told her that they had sold everything. Then one day she walked by their house and looked inside and saw them eating from her plates, and using her silverware, and the meal had been cooked in her oven dish. … They lied because they were never going to give them back.[7]

The only meaning of keepsafe not necessarily covered in those instances is that used by Isabel and her mother for whom ‘keeping’ means the opposite of using another’s ware, rather it mean deliberatively not using, not even touching them. Keeping and touching, however, are words that go deep in Isa’s psyche and guide her ability to relate to others, and the use of guardedness or more relaxed behaviour in relationships will matter in her history immensely, especially with Eva.

Rachel Sieffert, a considerable novelist herself, says with justification that:

Yael van der Wouden does not encourage us to like her protagonist in these opening chapters. Perhaps what we feel for Isa approaches understanding – but never more than that. …. / If we soften towards her, it’s through Hendrik. He pays his sister visits, sees the way she pinches at the back of her hand when she’s nervous, which is often.[8]

None of this I dispute but I think Sieffert fails to tie the handling of character to the theme of safekeeping though she rightly describes the effect of over guarded or over reserved characters on novel readers (it is after all an old trope used by Jane Austen with regard to characters who display overmuch ‘reserve’, perhaps even to the point of deceit, such as Jane Fairfax in Emma). The whole point of the more modern novel is the examination of the reasons for Isa’s guardedness – related often to guilt, but beginning to ‘loosen’ later in the novel both in terms of her brother Hendrik’s, and later she is to discover, her own, queer sexuality. Guardedness is too used with reference to understanding the sources of both her social and economic instability in some characters including Isa, that might be impoverished, without such loosening of moral and curatorial tone as a lover or family member.

Hendrik says of Eva’s effect on Isa that ‘She’s loosened you. It’s nice’. At that point however Isa is still rather more ‘screwed up’ than loose, though aware now that loosening is not as bad as some metaphoric sources suggest: ‘ “Loosening. As if I’m – a bolt, a rusted – “ Her voice did something odd. She calmed, …’.[9]

Van Der Wouden is brilliant at capturing how internal intrapersonal and external interpersonal dramas interact with each other in such moments (as with Tante Rian). Sieffert knows Isa is not very likeable in part because of her rigid attitudes to social life, the care of a home, the attention and care shown to friends and strangers and to the mixing of classes (notably the relationship of the bourgeois families to servants and waiters) but this is fundamental to the novelist’s display of a character locked into safekeeping. It applies to her own sexual life, at least that part of it that she allows to be conscious.

However, the novelist does this to brilliant effect because she allows us to see under the guarded pose, and perhaps even our own, and especially with regard to acknowledging that ‘touch’ of herself if not others is as fundamental to her life of the body as with anyone else. The description of her habitual masturbation is brilliantly coy in its guarded revelation. Of course, ‘arousal’ is an inconvenience’, ‘a blanket weighing her down’ but it is also ‘the drag of honey into lungs’, which, though it would of course choke you, is an image rank with the voluptuous. These balanced sentences suddenly tip into autoerotic delight:

It was rare that she gave into it. She hated the headiness, the wet, the excess of the experience. But then – … she would dip into herself. She would make sure she was still there; a body, a heartbeat, a toppling hunger between two legs.[10]

And, in ignoring the validity of the wet and excess of the period in which Eva and Isa learn of each other’s bodies and validate each other’s existence outside of either of their norms. Sieffert thinks that:

The novel gets stuck here too, though. The two women reach and grasp, have sex against door frames, on the floor, and at greater length than the narrative – up to this point – can accommodate. It just doesn’t move the story on [11].

The need that a story ‘moves on’ is as neurotic a need as that of getting ‘stuck’. They both happen in lives and novels but both have a valid role in defining human experience, even in the manipulated mobility of a novel’s plot. Van Der Wouden needs her characters stuck. Were they not, the meaning of the bits where, as in the ‘book’s third act’ where Eva narrates, in diary form, could ensure that, according to Sieffert,‘with her the novel comes into its own’. For the novel must and will resolve both the urgency of Eva’s story and the languorous swooning of that of Isabel’s story. A great critic (of Milton – read my blog of his work on that poet here) – Joe Moshenska says of the part of the narrative that Sieffert calls ‘stuck’:

The middle chapters of the novel contain a series of intense and brilliantly written sex scenes, unafraid of the sneering faux-worldliness that often greets attempts to write about sex even now that the Literary Review’s Bad Sex award has been suspended. Van der Wouden’s style both describes and takes on something of her protagonist’s tight self-control: “Isabel could see herself from the dresser mirror: face red, mouth like a violence.” This same style, brought to the moving awkwardness of intertwined human bodies, brings a wonderful power and precision.[12]

This is a better critical description of the taut sections of the novel Sieffert finds rather distasteful, with their brilliant use of scenes reflected in a mirror to capture the liberatory neuroticism of the whole, but one where both ‘wet’ and excess have a role to play. I miss critics who pick up on details, like the repeated use of mirror symbols, in the writing of writers who can truly write.

As an illustration of use of detail, let’s take this writers use of ‘mouths’ as both a feature of human faces, human sexual action and of articulation, eating, or the absence of each of the two latter. Moshenska cites a great example above: what Isa sees in her bedroom mirror is a ‘mouth like a violence’. This is metaphoric writing of great intensity. The treatment of the mouth is intensely related to the presence or absence of human touch. It is evidential of a touch – perhaps even more violent than a touch such as a bite (love bites are notoriously evidential in this novel, especially of queer sex but not only).

This is how Isa registers that others have been touched sexually and becomes almost a source of fantasy. After all in this novel she is predominantly a silent point of view registered by the novelist likewise silently: Sometimes the touch of this in the writing is light as a tentative registration of what Isa from her point of view sees – staring at Eva from a landing on the stairs above after her brother leaves her, as his girlfriend waiting for his return, we are drawn to her ‘mouth, kiss-swollen’.[13] It is a watched trait that deepens, registering Isa’s interest in how the woman she will fall deeply for has been touched and marked by others sexually. Much later Isa fantasises about how Louis might have marked himself on Eva, which becomes a way of negotiating how touching too can be a thing ‘kept’, preserved, like a mark made in the shaping of wet ceramics in formation:

She had a dent to her bottom lip, Isabel noticed – hadn’t noticed before. A dent like someone had pressed a thumb to her there when she was still taking shape, and the lip forever kept the pressure of that touch, Isabel wondered, briefly and horribly, what Louis had done to earn his first kiss from Eva. How he had touched her …. (my italics) [14]

The fantasy of penetrative touching, requested and then allowed, following this constructed memory is in Isa’s imagination only. Not so when the mouth is her own registering a real violence of touch on it that has perhaps physically been left by a kiss that has started as a ‘touch, a reaching thing’, is felt as another’s tongue in one’s own mouth and then (perhaps) a bite: ‘hot mouth wide, putting her teeth to Isabel’s lips’. Whatever occurs, when Isa ’touched her own mouth again’ in the morning after, she finds it ‘swollen. It felt bruised’. That chapter ends with Isa’s rumination marked by licking her sore lips but the psychological effect opens up a more terrifying psychic mark in the metaphor of what she has discovered about herself – a mouth opened in horrified terror at its own wants: ‘The terror was as wide as the want: a boulder moved from the gaping mouth of a cave’.[15]

The effect on mouths, whether suppressing a scream of denial, is marked in the episode wherein Isa discovers, before her mother, the evidential love bites of Henrik’s sexual adventure with his young male, but older than he, piano-teacher Edwin (a particularly predatory form of male in this novel). One such scene ends with Isa remembering stuffing a quilt in her open mouth to stop a scream, or articulation of her discovery of same-sex/gender desire in her brother, whom she once held in bed ‘through his night terrors’. She sees Hendrik not only bitten (‘the skin of his neck irritated into a mottle’) but dirtied by sexual touch. After a second incident, in which Edwin the piano teacher, has rejected Hendrik’s hungry and fearsome desire, Hendrik returns to receive a slap from his mother, having challenged the conventionality of her sexual imagination. Her wedding ring tears his mouth accidentally: ‘caught on his mouth, chipped a tooth, broke skin’. He allows Isa to attend to his bloody face and ‘bleeding lip’ on her knees. It is a charged scene in which Isa’s inner drama of being perhaps more like Hendrik than like her mother gets unsaid. Hendrik’s conclusion, ’I am not made for this place’, is a chilling realisation of the marginalising effects of heteronormativity.[16]

Mouths matter in the novel for they bridge the gaps with their quality of being a vacant orifice leading to some inner space with other domains of action in the novel than its brilliance of understanding of somatic sexuality: eating, articulation of language or expressive noise, or their absence. They register emotion at expectations or knowledge of the world – opening and closing in silence, or running dry psychosomatically.[17] In Eva’s diary, this unusually cool woman feels in memory the heat of another woman as a mouth (‘God help me. I can still feel her mouth’) and fears she ‘wants to eat me. I think she would inhale me …. I think she’d crawl herself inside of me as if she thought that’s where she’d find something that I’ve kept hidden from her’.[18]

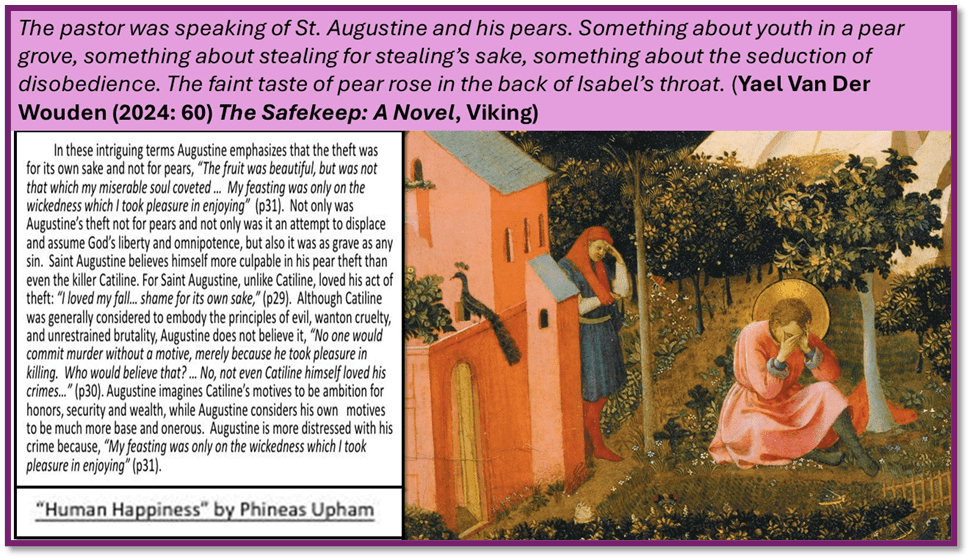

Eva’s invocation of the God of the Jewish faith in the last example is parallelled by Christian fantasies of the appetite in Isa. It again references eating, as the Christian doctrine of Original Sin does, though veering from Eve’s apple to St. Augustine’s example – because so much wetter and excessive like sex, a ‘pear’.

See, for instance, this luscious passage of wetness where, dared by Eva, Isa eats a pear in private that stains her skirt:

There was no way of eating it in silence – the sounds it made, the wet. … / Her arms were dripping. Wet all around her mouth. She had to wash her face in the basin afterward. / The spot on her skirt where the fruit had stained remained throughout the day, a cloying brush to the back of her hand.[19]

I defy anyone to find an evocation of touch so brilliant as that ‘cloying brush’ in any literature, by the way. The gloss on Augustine comes in the next chapter whilst Isa is in church:

Perhaps of mouths, though, we have had enough. The beauty of St. Augustine’s story of the pears is that it unites ideas of appetite contrary to God’s will (or that of heteronormativity), the shame involved in stealing – which in the novel involves the shameful story involved in the house Isa thinks of as ‘my house’ – and the policing of pleasure, especially in physical and wet carnality.

I don’t intend to write much on the stealing theme except as it touches on what a queer Jewish reader, Joe Moshenska, sees as its main undercurrent, as indeed does Rachel Sieffert though she fears spoilers in speaking of it. But I do need to take some distance again from the way Sieffert, a terribly good reader whose example means something, reads this theme in Isa; She says of her:

Isa suffers, too, under terrible loneliness. This expresses itself through a cramping kind of possessiveness. Covetous of the patterned plates and curtains that came with the house when the family acquired it, Isa insists all is tended and dusted and polished as her late mother would have wanted – and all the while she suspects the maid, Neelke, of cutting corners and pocketing teaspoons.

Sieffert gets all that right but the ‘cramped possessiveness’ needs human context – the fear that one is being stolen from is a basic response to human loss – it resumes very painfully in people with advanced dementia as a means of explicating psychic loss done in brain damage. In Isa it registers her repressed awareness of the fate of Jewish goods in the experience of the Nazi occupation and the imprisonment and execution of Dutch Jews, often with levels of complicity from the non-Jewish population but also the sense in Isa that her life is being locked up and kept in – like the ceramics in a vitrine. It is a novel in which some letting go of internal pressure in favour of love and pleasure is denied those who do not, like Hendrik, rebel, losing their family in part as a result. Isa eats pears sensually, for they are as stolen in association as Augustine’s. When her loved things might have come from the family of her Jewish beloved, the situation is even more complex. To respond fully in guilt and shame may be to lose everything, and Isa, unlike Eva, is never forced in that direction.

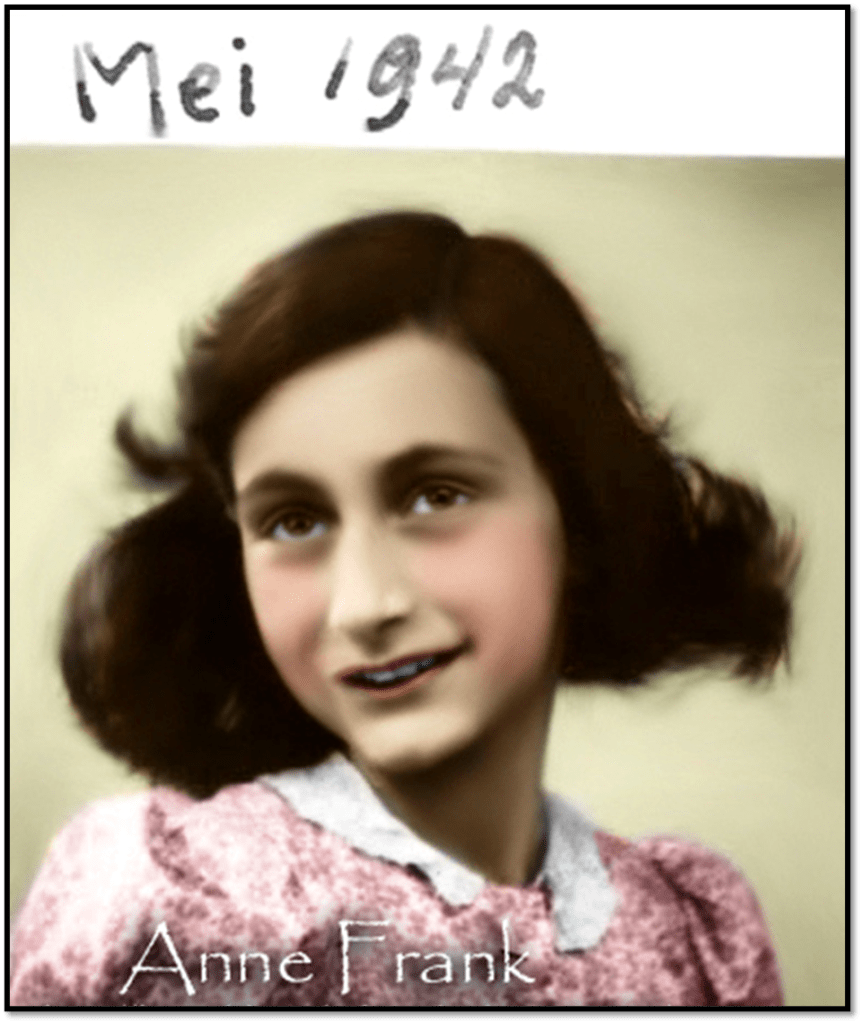

For Joe Moshenska, this is a sad but realistic (and realised) beauty of this novel, whose themes he traces back to Van Der Wouden’s work on Anne Frank:

On (Not) Reading Anne Frank, explored the ways in which that totemic, sentimentalised figure threatened to leave little space for her own explorations of her Dutch-Jewish identity; here she explores not the deportations and the mass murders but the quieter forgettings and self-justifications that came in their aftermath. “If they cared about it, they would have come back for it,” says one character of a Jewish family robbed of their home. “No. They’re gone. They’re gone or they don’t care. So many are gone.” Beneath such platitudes guilt lies buried.

It is a brave thing to go beneath European sentiment that pretends non-Jews were not collusive with Nazism in some small ways. Moshenska is perhaps right that the novel gives the non-Jewish respite from the hook of guilt in small redemption, although I think the story makes it clear that Eva has restored to her what is hers only at the cost of channelling her considerable bisexual energy on one person alone, Isa. But that you can decide. Moshenska says:

For a novel that is so unsparing in its dissection of the lies that individuals, families, and nations tell themselves, The Safekeep has a surprisingly upbeat ending, ultimately suggesting a confidence that more hopeful futures can emerge from the bonds that individuals form with one another. I realised in finishing it that my desire for something more was partly a futile desire for poetic justice that the novel had deliberately provoked – a desire for some kind of comeuppance for those who chose to erase, to forget, and to forget their own erasures. Van der Wouden’s point is that such acts are painful and routine. Moments of individual connection, when the painful twisting of one’s own skin becomes a reaching outward, feel fragile and inadequate, and all that one can hope for.

I don’t read the ending quite as Moshenska does. There is no Forsterian resolution in the magic of personal relationships that break through class barriers as in Forster’s novels, including Maurice. I think the ending tells truths about the negotiation of power relationships even in wished-for unions of couples. There is one in particular I want to concentrate upon. As the novel shows, the needs of non-Jews have to be accommodated in any resolution of diasporic Jewish grievance. For a Jew like Eva, to have somewhat of her own restored, never allows her to forget the ‘superior’ entitlement of the non-Jews to whom she owes it. The same is true, I think, in this intelligent novel of the intersections of identity formations for queer women, in contrast, say to queer men.

Hendrik may feel, as I have already cited that, ‘I am not made for this place’, but that is not a statement of a suicidal or even repressive response but of some kind of limited rebellion, which eventually aligns him with the beautiful Algerian, Sebastian, whose experience of French racism against its supposed part of France that is in Algeria intersects with the queer theme. Hendrik and Sebastian do not have it easy therefore but their path to fulfilment is not as hard as that of isa because he is a man, and has opportunities and ideological freedom to make somewhat of himself.

This is not so with Isa who is, like Eva in a way that the latter manipulates very much better, bound to a predicted future in heterosexual marriage and children.[20] Even Hendrik, a queer man who ought to know better, supposes that to be her future and just assumes she will marry the cultureless and easily-made-hard Johann: ‘Must I save the date? A summer wedding, an autumn wedding.’ Hendrik insists as he demands evidence of what went on in Isa’s dinner engagement with Johann, until she says ‘Stop!’. But even this is thought to be female prudery about sex.[21] The point for Isa is that she alone bears the guilt for her family’s overtaking of Eva’s domestic heritage, whilst anyway having no claim to it for she is felt to have enough assets in being merely marriageable.

Hendrik, a younger man, never quite understands that though he is aware that his uncle’s belief in primogeniture mean that older brother Louis will inherit the family house on his marriage, if it ever comes to that lightly given man. Eventually Isa, failing with her uncle Karel, must work on Louis to make him realise a woman’s vulnerability financially, especially if a queer woman, the dialogue where Isa says the unsayable to Louis to keep the house for herself (and Eva but she doesn’t say that), comparing her reasons for not marrying to Hendrik’s is masterful dialogue of its kind – the kind where a woman may not say she is lesbian and will never look for a man to house and safekeep her. Once Louis realises what she is saying by ‘’I will never marry. Hendrik will never marry and I will never marry. Do you understand?’ Understanding is hard in coming, and when it comes we return to the expressive metaphor of silent open mouths: ‘He opened his mouth, closed it’.[22] She gets the house but only by breaking through male refusal to understand female sexuality except as a response to the hardness, like Johann: ‘He pressed his body close, purposefully. She could feel him through his trousers – the shape of him, raised and excited’.[23]

From some touches, purpose and assumptive, Isa needs to keep herself safe. Her brilliance as a character is that achieves that but not without us knowing the strength it takes from having ‘the shape’ of a heterosexual man’s sex imposed on her. This is a brilliant novel though, and perhaps because, it made me realise, that queer men sometimes are as neglectful of the oppression of queer women as straight men, however lovable they be like Hendrik. He feels the racism directed at Sebastian – does he feel his collusion against queer women realising their own self-expression.

There are so many beauties in this novel – the treatment of time, weather and landscape and the writing thereof, which explores innovatively the pathetic fallacy we thought we had left behind with the novels of George Meredith is one. One taste perhaps to speak for itself: ‘January lowered itself over Amsterdam and would not rise again’.[24]

Read this novel. It will shock. It will give hope. It will make you feel how prose grapples with the interaction of internal and external attempts to capture reality and real power and desire in relationships.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxTop of Form

[1] Yael Van Der Wouden (2024: 3) The Safekeep: A Novel, Viking

[2] Ibid: 258

[3] “In this manner guard justice and act rightly for My Salvation is near, and My right action is about to be revealed.” Is verse 1 of Chapter 56 as glossed by Yaakov Brown available at:https://www.bethmelekh.com/yaakovs-commentary/isaiah-56-a-house-of-prayer-for-all-the-tribes

[4] Yael Van Der Wouden op.cit: 258

[5] ibid: 3

[6] Ibid: 226f.

[7] Ibid: 187f.

[8] Rachel Seiffert (2024) ‘Review: The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden review – the Dutch house’ in The Guardian (supplement) [Sat 25 May 2024 07.30 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/may/25/the-safekeep-by-yael-van-der-wouden-review-the-dutch-house

[9] Van der Wouden op.cit: 108

[10] Ibid: 112

[11] Seiffert op.cit.

[12] Joe Moshenska (2024) ‘Review: The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden review – secrets and sex in postwar Europe’ in The Observer (Sun 16 Jun 2024 16.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/article/2024/jun/16/the-safekeep-by-yael-van-der-wouden-review-secrets-and-sex-in-postwar-europe

[13] Van der Wouden op.cit: 40

[14] Ibid: 94

[15] Ibid: 77f.

[16] Ibid: 84- 87

[17] For examples, ibid: 57, 135, 246

[18] Ibid: 214f.

[19] Ibid: 51

[20] For Eva, ibid: 202

[21] Ibid: 97

[22] Ibid: 239f.

[23] Ibid: 135

[24] Ibid: 241

2 thoughts on “‘The Safekeep’ is well titled since it is a book about why we attempt to guard from others those things we find most precious, keeping them locked from the touch of strangers. This is a blog on Yael Van Der Wouden (2024) The Safekeep: A Novel”