The prompt question today recalls the phrase used in English, ‘May you live in interesting times’? It is known, without much supporting evidence as the “Chinese curse“. In the LibQuote above, it is attributed in longer form to Robert Kennedy, and he elaborates it in seeing turbulence in history as the more interesting option. In the apocryphal Chinese form, the implication is that the danger and negative risk of being in ‘interesting times- of civil, national or international conflict – outweigh the positive risk of creative involvement.

Wikipedia argues that ‘the saying is apocryphal, and no actual Chinese source has ever been produced’ and that the ‘most likely connection to Chinese culture may be deduced from analysis of the late-19th-century speeches of Joseph Chamberlain, probably erroneously transmitted and revised through his son Austen Chamberlain‘. Nevertheless the Wikipedia article does go on to cite a rather close analogue to the phrase in Chinese as in the citation below:

The nearest related Chinese expression translates as “Better to be a dog in times of tranquility than a human in times of chaos.” (寧為太平犬,不做亂世人)[3] The expression originates from Volume 3 of the 1627 short story collection by Feng Menglong, Stories to Awaken the World.[4]

The origin in the speeches of Chamberlain is attributed (again in Wikipedia) in a letter of his son to Frederic René Coudert Jr. which contains the following assertion, if Coudert’s transcription is valid:

“Many years ago I learned from one of our diplomats in China that one of the principal Chinese curses heaped upon an enemy is, ‘May you live in an interesting age.'” “Surely”, he said, “no age has been more fraught with insecurity than our own present time.” That was three years ago.[7]

The date of the letter was 1936, three years before ‘interesting times’ ensured that Chamberlain was to become the most despised Prime Minister of the UK for trying to find ‘security’ in a piece of paper offered to him by a world adventurer of darkly chaotic proportions, Adolf Hitler. Britain entered the Second World War under Churchill, with nothing to offer it but ‘blood, sweat and tears’ and maybe the adventure of ‘fighting them on the beaches’ or wherever they come at us.

The point is that ‘interesting times’ may provide the context of ‘adventure’, but they also threaten our security, our lives, and our chance of living an ordered life. Even in fiction, adventure is found in battle (righteous – or even unrighteous – conflict) as a warrior, or (for an unrighteous example) a pirate. The iconic example of this choice is Robert Louis Stevenson’s Jim Hawkins, torn from the relative security of his home into adventures on the high seas and in pursuit of high monetary stakes and collusion with the pursuit of gain in dangerous times and places with shady characters like Long John Silver on Treasure Island. But even here, Hawkins has a choice – to identify with the forces of the gentlemen of the ‘sea’ whose fortunes rise and fall in ‘adventure’ (wild, adventurous and risky) and the ‘gentleman’ of established birth and socially validated secure status in the static land of England – A Squire (Trelawney) and a Doctor (Livesey).

Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treasure_Island

Stevenson’s point in that strangely dark fable is that security really is only security for the entitled for whom life struggles take place at a distance and in proxy, by the tenants of the landed or the workers or the struggling workers of the capitalist, whose adventures are played out in the part of their money invested riskily, provided they are supported by safe and secure investments elsewhere. The insecurity of adventurous life is not all ease, as the alienated form of Ben Gunn, alone on an island full of treasure of no use to him, shows.

Usually a prompt question like this is only asked where ‘adventure’ and ‘security’ are notional and abstract, of people who have already enough security to afford to buy a window of adventure in an expensive form such as sky-diving or mountaineering. The risks remain in these but they are bolstered by insurances and safety checks. The feel of adventure to those over-aware of its risks feel like they did to Hamlet in Act 1 Scene IV, line 189ff. of the play Hamlet.

The time is out of joint: O cursed spite,

That ever I was born to set it right!

Nay, come, let's go together.

In the security of armed friends they descend to the joys of the court of which Hamlet is the heir, but aware that ‘interesting times’ are upon him: the armies of Fortinbras of Norway on his nation’s margins and his stepfather the accused (by his father’s Ghost) murder of his father and now married to his mother. Setting that right is an adventure again, that like the over-adventurous play of children, parents longing for rest from it say that it will ‘end in tears’.

I think I can imagine that it might be better to be a “a dog in times of tranquility than a human in times of chaos,” although dogs are treated badly globally however secure the humans who claim to care for them, but that is not a choice we will ever be given. And it has a kind of country folklore feel to it that saying, as if it came from a situation in which life is hard enough already, as it was for the agricultural poor in China for successive regimes, including those of Communism. It is not between choice of security against adventure, but that between a form of living in insecurity kicking against ‘outrageous fortune’ over which I have little control and having less control because mighty people want to plunge me into adventure.

On the other hand, sometimes Kennedy is right. The comfortable and entitled need that most people seek a life out of any limelight of adventure, for our right to what we feel ‘good’ for us is dependent on them blindly working for little and achieving what we appropriate, as either the successors in time or superiors in class, status or role. That is the dark side of George Eliot’s famous saying in Middlemarch. Adventure is bought for the entitled by the willingness of those who wish to continue in living through ‘unhistoric acts’, by which is meant unrecorded acts.

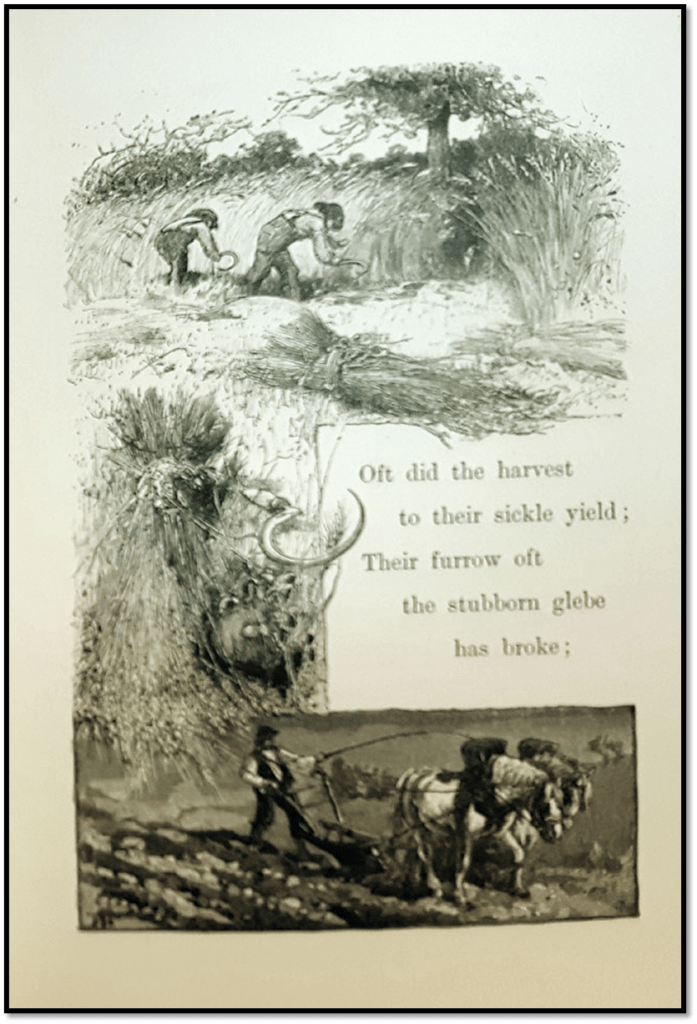

It is the same sort of sentiment as in Gray’s Elegy Written in A Country Churchyard. When Gray says:

The curfew tolls the knell of parting day, The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea, The ploughman homeward plods his weary way, And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

We too often read these lines lazily, Gray not being thought much cop as a poet, but take that word ‘leaves’. We leave things in our will to our descendants, or we ‘leave’ the stage of action in order to allow the entitled to their scene of either adventurous or passive glorious reflection. Whatever, the ploughman is so absorbed and shattered by his labour that he barely notices the leisured gentleman absorbing all of the world, including that he, the ploughman, has worked to contribute to the world, whilst the gentleman lives on the profit of either or both land and capital with leisure for sad but accepting reflection on the goodness of the status quo, even its inequalities of labour, remuneration and record of what we leave behind in our lives. If you read the George Eliot quotation again, you see that there too. I am sure she was aware of it – her fiction on reflecting from an achieved middle-class status back to the hardships of her family, the Adam Bedes of this world.

What Gray and Eliot both do is record the ‘annals of the poor’ themselves, and pose them in the genre of adventure the entitled feel belongs to them. Look at the choice of words in the following:

Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

How jocund did they drive their team afield!

How bowed the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile,

The short and simple annals of the poor.

Ambition is ambition for a world of adventure – of mind, spirit, body, land or capital. Yet ploughing is described in the language of adventure -with Latinate and medieval archaisms abounding. there is a battle of fighting against the resistance of the enemy sod beneath the plough to make it ‘yield’, there is a team spirit in the ‘team’ of shire horses like the team that fought Agincourt. There is regal grandeur to which we ;bow’. Nevertheless glorify them as we will, we ought to to reflect that these rude forefathers were rude because they were denied the ‘goods’ others took for granted – adequate sustenance, education and leisure, even to rest other than in their graves.

So don’t ask if I want ‘security or adventure’! It is a loaded question, as I hope I have shown.

With much love

Steven xxxxxxxxx

Well done

LikeLike

I agree

LikeLike