Ernst Krenek‘s classification, from ‘Studies in Counterpoint’ (1940), of a triad’s overall consonance or dissonance through the consonance or dissonance of the three intervals contained within. Created by Hyacinth (talk) 17:07, 25 September 2010 using Sibelius 5.

We can’t get far with this question without reference to music (and I am hampered by a total ignorance of musical terms and their use by musicians), but it is equally certain that the history of music seems to a musical ignoramus like me to depend on a socio-cultural evaluation of how people live together in groups, whether families, communities, nations or at a global level. Harmony since the term was used in Greek (ἁρμονία harmonia, meaning “joint, agreement, concord”) has this double usage, important to both a developed aesthetic of music and and an understanding of social organization and regulation. Greek democratic life (for those not slaves – or women – at least) was necessitated on utilising the discordances of conflictual debate as part of achieving the concordance of a people and guaranteeing its unity of purpose, though real history often diverged from political theory. The most interesting (to me) aspect of this analogy is the interplay of notions of consonance and dissonance as a development out a notion of harmony confined to hearing one voice only, even if that one voice was a production that occurred over time. According to Wikipedia the shift of meaning in Western music occurred during the Middle Ages:

In Ancient Greece, armonia denoted the production of a unified complex, particularly one expressible in numerical ratios. … Until the advent of polyphony and even later, this remained the basis of the concept of consonance versus dissonance (symphonia versus diaphonia) in Western music theory.

In the early Middle Ages, the Latin term consonantia translated either armonia or symphonia. Boethius (6th century) characterizes consonance by its sweetness, dissonance by its harshness: “Consonance (consonantia) is the blending (mixtura) of a high sound with a low one, sweetly and uniformly (suauiter uniformiterque) arriving to the ears. Dissonance is the harsh and unhappy percussion (aspera atque iniocunda percussio) of two sounds mixed together (sibimet permixtorum)”.[46] It remains unclear, however, whether this could refer to simultaneous sounds. The case becomes clear, however, with Hucbald of Saint Amand (c. 900 ce), who writes:

Consonance (consonantia) is the measured and concordant blending (rata et concordabilis permixtio) of two sounds, which will come about only when two simultaneous sounds from different sources combine into a single musical whole (in unam simul modulationem conveniant) …

The separation of an interest in sounds produced in music from the social sphere is not as real as it sounds from treating this issue as merely about music and musical theory when Wikipedia seems to do that very thing here as it discusses medieval theorists. Medieval political philosophers were as interested in social consonances and dissonances between distinct socio-political groupings, like Church and State, nations and specialisms of trade and occupation as was the Attic state in resolving the geographical and class conflicts in its subdivisions of the city-state or polis of Athens.

To some, medieval thinkers, politics was as much a discussion of music since Thomas Aquinas had seemed to prove that there was an ordered measurable music in the spheres of the cosmos, subject to a First Mover, God. But none of these philosophies wanted an eradication of the unpleasantly dissonant: such sounds had a purpose in making us aware of the dangers of conflictual violence in the material world and its distance from heaven.

And, as in the music, it was felt that humanity needed to be aware of the unpleasant and jarring in order to understand the process of the transformation of discordance into concordance in our interval on earth, dis-chords into chords, becoming harmonic together over time. We are not a hundred miles away from that great simplification of Hegel’s theory of history (and Marx’s adaptation of it) that is the dialectic, where a thesis and an antithesis combine in timely progress to a synthesis.

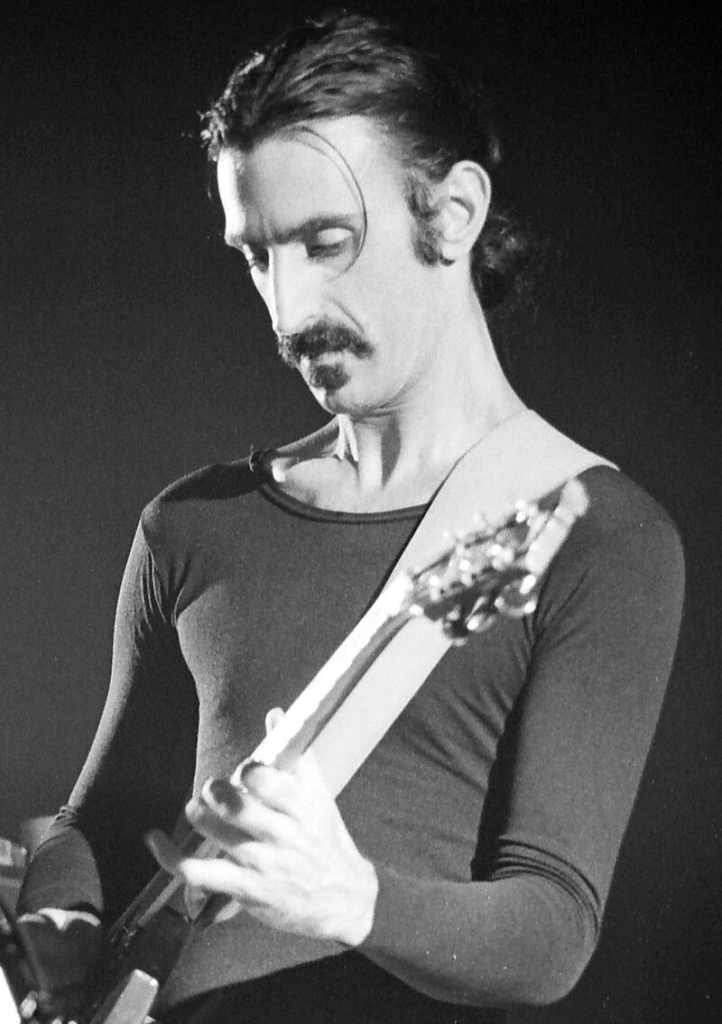

Some improvisational musicians in the twentieth century were as equally aware of the political meanings of the dissonant in popular form like jazz. They might like Frank Zappa have expressed their views on music in line with their views of the necessity to kick against the pricks of convention rather than in directly political terms, as in blues singing. For Zappa, dissonance was a necessity of a temporal drama as in the Boethius and Hucblad.

| Frank Zappa, Ekeberghallen, Oslo, Norway | |

| Date | 16 January 1977 |

| Source | Own work |

| Author | Helge Øverås |

The creation and destruction of harmonic and ‘statistical’ tensions is essential to the maintenance of compositional drama. Any composition (or improvisation) which remains consistent and ‘regular’ throughout is, for me, equivalent to watching a movie with only ‘good guys’ in it, or eating cottage cheese.

Frank Zappa, ‘The Real Frank Zappa Book’, page 181, Frank Zappa and Peter Occhiogrosso, 1990 cited https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmony

We need conflict, this quotation seems to suggest, for the sake of an aesthetic whole, only interesting at the level of the whole work or ‘composition’ if there is the drama of conflict.The work, though, is still composed at the level of the whole only, and the social and psychological meanings of being composed and discomposed equally apply to the ‘tension’ between its parts. How can we ever become composed if we do not experience discompsure? It may be that Zappa, like a medieval theologian, needed the dissonance of evil and bliss-denied angst, in order to praise a consonant whole, which despite intervals of dissonance, still has people singing from the same hymn sheet’ (in the popular term). That is so even though they do it only for the sake of not being boring (as cottage cheese is boring) or without tension (as in a crime or Western genre novel that actually keeps you reading).

So, to the prompt question! Do we need in fact to lose anything, ‘for the sake of harmony’. The lesson in the above seems to be we do not have to lose it. In fact we need the experience of dissonant conflict to show the workings of a consistent theory of history that tries to understand conflict as in Hegel and Marx, or the principles driving the First Mover of the music of the spheres, dissonant in the world of the mortal only, in medieval theology, or the workings of direct democracy in Greece (or to ensure we don’t get bored with life, as with Frank Zappa). But losing things is not what the question asks. Rather, it asks if we will ‘let things go’ that cause dissonance in our harmony. And in fact, yet again this is consonant with the theories above. In music a discordance resolves itself to achieve harmony over time. This Wikipedia paragraph explains that conundrum clearly:

Typically, in the classical common practice period a dissonant chord (chord with tension) “resolves” to a consonant chord. Harmonization usually sounds pleasant to the ear when there is a balance between consonance and dissonance. Simply put, this occurs when there is a balance between “tense” and “relaxed” moments. Dissonance is an important part of harmony when dissonance can be resolved and contribute to the composition of music as a whole. A misplayed note or any sound that is judged to detract from the whole composition can be described as disharmonious rather than dissonant.

But we have to notice that tis principle is absolutely true of music only in an interval in history, of about 250 years in music: ‘the classical common practice period ‘. It was the product of social ideologies – strained but still operative in Romanticism where dissonances of grief, madness, personal disintegration and solipsistic alienation were a dramatic necessity in music as they are in Zappa. I am working my way towards a blog on Judith Chernaik’s book (for more on this see my blog at this link) on the great Robert Schumann – whose component parts were often in showy dissonance like the characters Florestan and Eusebius, whose interaction amongst others, he hid within in his early music and sometimes his queered heterosexuality).

In brief, where we get to in the musical analogy is that harmony is about letting go of things that are dissonant for the sake of an eventual harmony in time at the level of a wholeness in our work. But that idea works only if you are clear you have to invite those things you later let go into your work in the first place. Life is a messy business; its finale of trenchant chords has not yet fully played out as long as it remains life. It is a composition in becoming not in completion, and it is fallacious to think that you can get rid of every instance of conflict and dissonance and leave life still undamaged. Let one dissonance go, and you become aware of others, either hiding from you or just arrived within your notice, either because they are new or because you hadn’t noticed their significance before.

And even in the moment of death, letting go of life rarely allows the dissonance you lived within to die. The insanities of grief in Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia paper are the sisters of mourning, endlessly raking over their complicity in a death they could have stopped happening perhaps or which unconsciously they had wished and thus for which they need to punish themselves, or others.

Should we keep wishing for life without conflict and contradiction? Perhaps not. It is better to chase away such wishes! They are daydreams. We can not let go of all conflict easily without letting go too of the life that holds it together with its resolutions, however delayed. Let’s pray we survive those wishes abd relishjour resistance.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

2 thoughts on “The fragile harmony of consonance without intervals of dissonance. In praise of the role of conflict.”