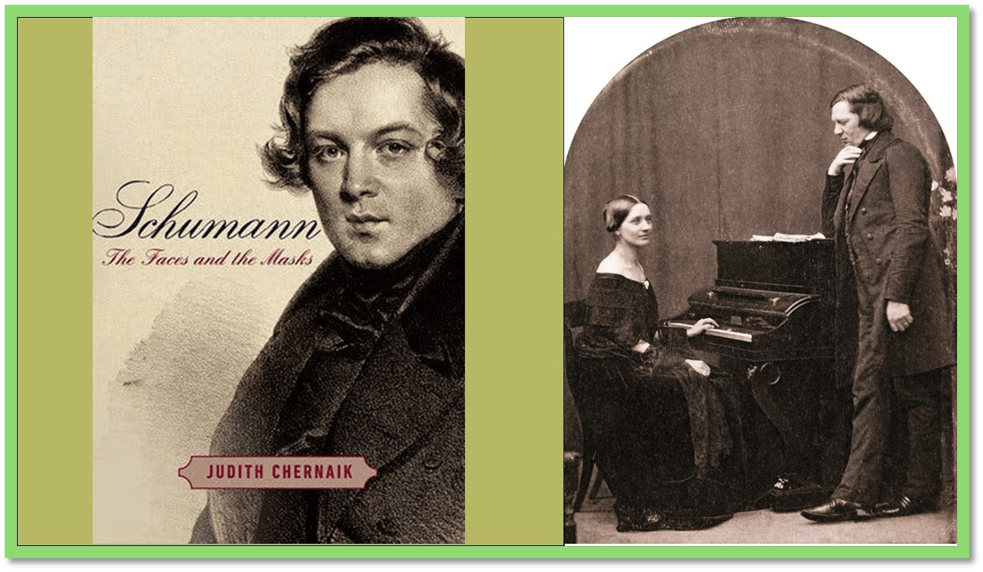

Beyond ‘genre’, liking and favourites: understanding what isn’t already in your culture is the priority. This blog is a plan to repair a small corner of the tatters of my ignorance of and feel I have some way of understanding the life of Schumann without neglecting the music. This is a blog based on Judith Chernaik’s (2018) SCHUMANN: The Faces and the Masks New York, Knopf Ltd.

I can’t presume to like any genre of music, however you interpret that contestable word, for music is not in my culture and no medium is more acculturated I think than music. It seems to me that even the capacity to hear music depends on our memory and expectations of patterns of sound alone working cooperatively with the input received from music’s transmitting agents (let’s forget voiced lyrics for a moment). It is the presence of this collaborative effort that is the sine qua non (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sine_qua_non) to which we respond.

I wonder why I don’t see this is my own nature as a responder to art, for sound envelopes all of us and certain genres of sound pattern dominate in any culture or niche culture. Analogous responses are highly developed in me in relation to language (even language in rhythmic and assonant patterns) through education and accident of experience. However, in music so much depends on educated development (or conditioned response paradigms in the lowest possible definition of the process) of its auditors, without at all reducing the role of the makers and media of those sound patterns. The barriers or portals that auditors can set up, or that can be set up in them, are crucial to whether music enters into their lives at all.

Music lessons for me at school were a nightmare. We had a teacher who showed his displeasure by throwing things (sometimes heavy things but never fragile ones) at any learner who, in his view, caused this displeasure. He would play a recording and shout ‘Instrument’ at certain points and you had to note the instrument or instruments playing at that precise moment, although the answer ‘Tutti’ (all of the available orchestral instruments in the characteristic Italian of the classical music convention) was also acceptable.

At the end the lists of instruments of each pupil were marked and the people with low scores humiliated; the ‘silly’ answers being read out with much encouragement to laugh at the ‘idiot’ who thought such an answer acceptable. Music to me was a thing of horror, reserved for the middle-class kids at my grammar school who often had private piano or violin lessons at home. But the alienation was also from the rock rebels in making, who had had electric guitars bought for them (grammar schools felt so alienating to working class entrants). One of the private pianoforte-lesson recipients fascinated me. His name was Ian, and he used to boast at the strength piano practice gave his fingers, flexing them in front of my fascinated eyes. In those days, those fingers looked lovely to me – but that is another issue.

The outcome was that music, even popular or élite contemporary music, never really interested me. Nevertheless I noticed that, despite a lack of acculturated response to any genre of music, I could feel my nervous system strain in patterns of tension and relaxation hearing certain combinations of sounds like that caused in the conversation between instruments in Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante (which I came across in the halls I lived in in my first year at University College London) but somehow that never made me feel that I needed to listen to whole pieces of music (at least whilst in my grammar school in West Yorkshire). As I suggested, in my first year at University I began to have a passion for a limited number of pieces of Beethoven, Mozart and Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

Schumann fascinated me, although I couldn’t take whole pieces then, because of the peculiarly patterned play between tension and relaxation, and a whole range of other complicated emotional effects in bits of his music, friends of a classical passion played for me. Nevertheless, that fascination fed into the myths of Romantic ‘madness’ so associated with Schumann, as if he were torn apart by the visceral music of his tensions and never fully healed by the relaxations of these tensions. It was as if I read my limited hearing experience through Mario Praz’s The Romantic Agony, a definitively necessary book in the UCL literature course, as led by Frank Kermode.

The myths of a Romantic lover of ideal images of the beautiful and true, torn apart by passion, like Orpheus, were obviously widespread though I did not know that so much before university. Of course Schumann was an embodied human being not a schema. These days we can be fairly sure that the final degeneration of Schumann’s nervous system was a syndrome associated with ‘tertiary syphilis’, for which he took mercury treatment in 1831. Even before this stage of syphilis infection was proven as normal to the disease’s progression in 1905, people had noticed the association in famous cases since the eighteenth century, and it appears from Chernaik’s recording of his notes to his doctors that Robert Schumann made it for himself, though his medical practitioners seemed happy to attribute it to “excessive mental exertion”.[1] And it was this myth of the man exhausted by both passionate and intellectual exertion that fascinated me, someone who made the feelings of strain I felt in secret believable and worthwhile rather than traits to be hidden and despised in myself.

Thus for me Schumann was added to a list of artists, (mainly working in language) I knew better, whose mental states mirrored their genius, a kind of remnant Romantic myth I still allowed myself, despite a supposed commitment to the rational critique of art represented by people like I A Richards or the historicised critique of literary culture like that of Frank Kermode (or Raymond Williams). Nevertheless I still had, and resisted having, no real knowledge of music, and certainly no skills in it. I expressed this in a recent blog post (at this link). Yet Schumann still haunted me.

I so much wanted to read a biography of Schumann I bought a year ago when the American edition was remaindered, but still (I was 68 by then) felt put off by the likely effect of my ignorance. I cannot read musical notation and had little or no acquaintance of hearing or using even the basic terminologies used to describe the elements into which a musical piece could be analysed, or even the exact meaning of the very basic structuring conventions and their names of classical period genres, like the symphony for instance (which most assume they can define). The notion even of what a movement in a symphony or other classical period piece was even rather foxed me.

And this mattered because when Schumann, as I was to learn from Chernaik and my little study described below, so experimented with the architecture into which a whole symphony or concerto was divided, by for instance diminishing the breaks between movements, in Symphony no. 4. He eradicated such breaks altogether so that the piece had to all intents and purposes only one perceptible movement. Of course, the whole point was that it still had four movements, but the ability to distinguish that fact, and its utility or other value to the musical experience, was part of the process of understanding. Maybe even the insistence on an ‘extra’ movement’ into the Third (Rhenish) Symphony was another play with the same highly acculturated tools.

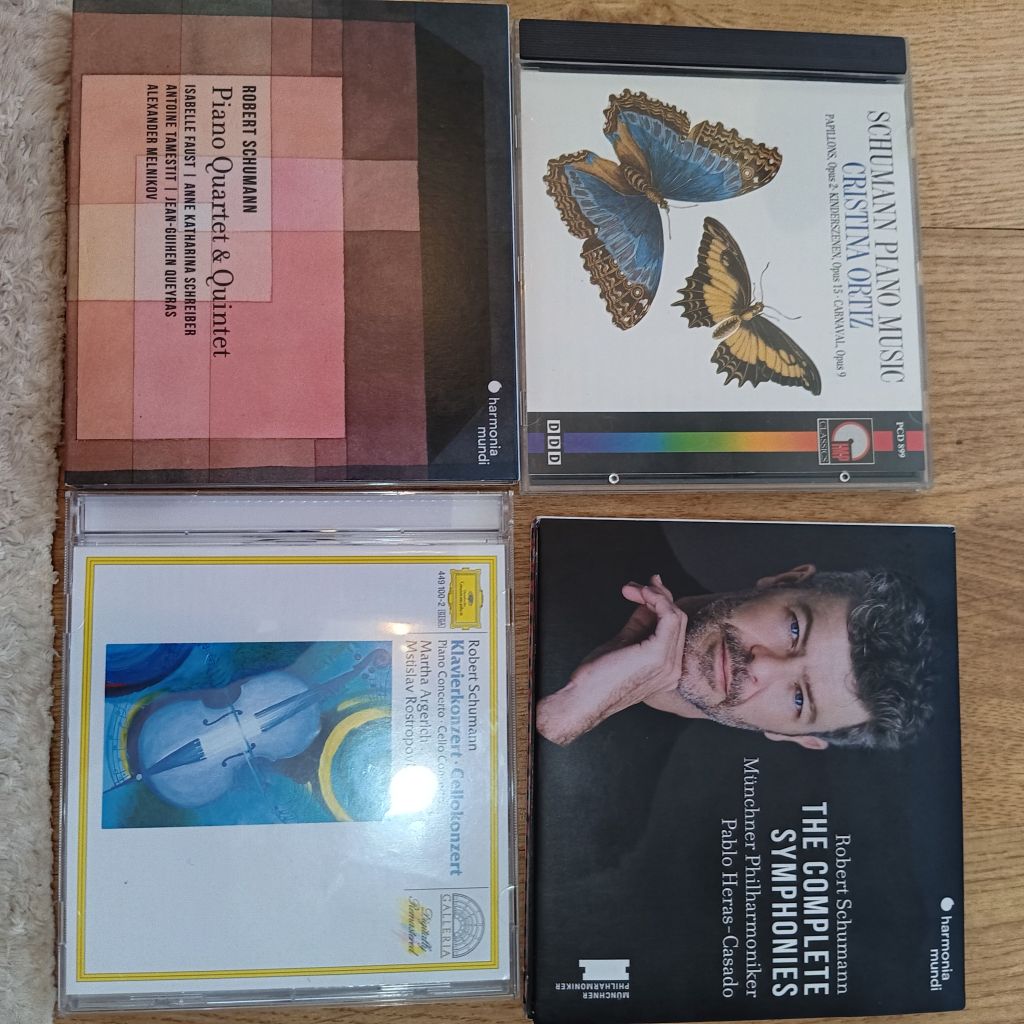

Chernaik’s biography intended it seems to educate its readers musically and this was an opportunity I could not forego. She says in her Introduction that she was going to encourage me ‘to listen to his music, the major works above all: Carnaval, the Fantasie in C, the song cycles, the Spring Symphony and the Rhenish Symphony, the joyous Piano Concerto, the Popular Piano Quintet’.[2] She mentions others but there already was a learning plan, however I might adapt (I have not heard as yet the Fantasie in C). My aim was to see if such a plan worked and with what success and encouragement to learn more. Hence, I sought to source CDs that I could get at a price I could afford, and then read the book, stopping off at the moments in his life, where each pieces I had sourced appeared and listen to it there and then.

Below I reproduce the table I created in rough, as I proceeded to show how that worked I hope that, at least, anyone looking at it (if anyone) can assess for themselves the viability of this learning project, should they wish to attempt it themselves. The table allowed me to listen and reference, or reference and listen, moving respectively between book and recordings) and to recap what seemed to be learned or go over what felt still resistant and that I still wanted to know better. The danger of course of the process is that my reading is guided by Chernaik, though I also consulted the CD programme notes for each piece. But one has to start somewhere in educating skills that don’t previously exist. I was not though expecting great strides into enlightenment, only a slightly better understanding.

| Order | Work by Schumann, with opus number | Source CD | Pages of ref. in Chernaik |

| 1 | Papillons opus 2 | Schumann Piano Music Christina Ortiz Recorded in this sequence 1, 3, 2. (ISBN: 5010946689929) | 24-27 |

| 2 | Carnaval opus 9 | 34-38 | |

| 3 | Kinderszenen opus 15 | 93-96 | |

| 4 | Spring Symphony (1st), Opus 38 | Robert Schumann: The Complete Symphonies Münchner Philharmonic Orchestra, Pablo Heras-Casado Recorded in this sequence 1 (CD1), 4. (CD2) (ISBN: 5149020944325) | 147f. |

| 5 | 4th Symphony Opus 120, 1851 version | 150-153 | |

| 6 | Piano Quintet Opus 44 | Robert Schumann: Piano Quartet & Quintet Isabelle Faust (Violin), Anna Katharina Schreiber (2nd violin in Quintet), Antoine Tamestit (Viola), Jean-Guihen Queyras (Cello), Alexander Melnikov (Piano) Recorded in this sequence 2, 1. (ISBN: 3149020947425) | 163 |

| 7 | Piano Quartet Opus 47 | 164 | |

| 8 | Piano Concerto in A minor, opus 54 | Robert Schumann: Klavierkonzert, Cellokonzert National Symphony Orchestra, Mstilav Rostropovich, Martha Agerich (Piano) Recorded in this sequence 1 (ISBN: 028944910025) | 188-192 |

| 9 | Symphony in C (2nd) | Robert Schumann: The Complete Symphonies Münchner Philharmonic Orchestra, Pablo Heras-Casado Recorded in this sequence 2 (CD1) (ISBN: 5149020944325) | 193ff. |

| 10 | Cello Concerto in A minor, opus 129 | Robert Schumann: Klavierkonzert, Cellokonzert Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, Gennadi Rozhdestvensky, Mstilav Rostropovich (Cello) Recorded in this sequence 1 (ISBN: 028944910025) | 232 |

| 11 | Rhenish Symphony (3rd), opus 97 | Robert Schumann: The Complete Symphonies Münchner Philharmonic Orchestra, Pablo Heras-Casado Recorded in this sequence 3 (CD2) (ISBN: 5149020944325) | 233 |

So how useful might such a guide to learning be? Jeremy Denk, a concert pianist who reviewed the Chernaik book for The New York Times when it came out in 2018, seems to suggest what you thought might be obvious that:

It won’t cure your problems, or the world’s, but it can’t hurt to immerse yourself in the music of Robert Schumann, a man who knew how to love. No less an authority than Sting agrees. I know this because Sting once put his hand supportively on my back while I practiced the postlude of Schumann’s song cycle “Dichterliebe,” and I haven’t washed that shirt since.

The point about reading the life of a musician must I think lie in an appreciation of their art, and for me that involves, as it does not for Denk (and Sting I presume), a bit of learning about a musician’s life process of creation and making and some puzzlement about how to appreciate the actual music on the way. Later in the review, Denk shows us that some people who profess to critique music also need some education in listening such that their understanding involves feeling viscerally the music’s content. It is clear however that though learning needs are elusive (embedded in how we listen and feel together), some will never be able to learn them and indeed, seem to think they are beyond learning (a characteristic too often found in academia as well as journalism).

Schumann’s elusive genius has allowed for a lot of naysayers. In a recent Wall Street Journal review of this same biography, the writer gives credit to Chernaik’s narrative work but can barely find time to praise Schumann’s music. He refers to Schumann’s spirit as “exhausting,” poking fun at his ardor (sic.): “Today’s reader might confront such a person and ask him to calm down.” He lists standard concert works but omits almost all the essential ones: the joyous, meltingly beautiful Piano Quartet; the Violin Sonata in A minor; and the surge of early piano pieces, including “Carnaval,” “Kreisleriana,” the “Fantasie” and — for many pianists the holiest of holies — the “Davidsbündlertänze,” a piece that rewards each listening more than the last.[3]

This still, as does Chernaik, sets up mountains to climb for me. I now know just how fascinating was the concept, devised by Schumann entirely out of the need to elaborate notions antagonistic to the values of the increasingly hegemonic mercantile or ‘Philistine’ world (which reduced musical value to the exchange value of commodities) of communities of embodied spirits.

These communities represented the aspiration to things more transcendent than the ‘Philistines’ conceived to be possible. However, I could find no available recordings I could afford of that piece, although the basic idea of a community of intellect, emotion, sense and spirit (passed of as ‘music’) is built into works too that I did hear – notably Carnaval.

Denk’s point remains however: why did the Wall Street Journal reviewer feel themselves qualified to judge the work at the level of ‘analytic’ abstraction they did – divorcing Schumann’s life-story from his life-work. That error, my method, laughably based on ignorance as it is, would avoid at least..

Of course attempting to understand an artist’s life, outside of music, if it is possible to make this distinction, is an unavoidable issue in musical biography. In Schumann the divorce is difficult to make. Schumann, according to Chernaik, took genres and made them malleable to input from his life – both that he lived in the body and that he imagined (all though that seems visceral too, in this artist). He divided his early pieces into sections, not always discernible and this need to both analyse and synthesise, to blur parts and wholes as they are processed in making and reproduction, seems essential to Schumann’s art, as indeed many other Romantics. This is so in Papillons and Carnaval – at once both narratives of a ball inhabited by a band of an anomalous proto-artist figures (from the Commedia del’ Arte tradition in particular) used to section up the piece, or supposedly so) and at another a series of kinds of attitudes in contest and debate (characterised by a butterfly series in the first). These pieces play games from the start with concepts of form, performance, and the reception of both.

These elements Robert felt he took from the cusp of his imaginative and real life (a cusp of incredible breadth), including amidst them two primary figures representative of his divided self in no clearly understandable way: Florestan and Eusebius. Even understanding the genius of these characters is a difficult process, both representing traits (political, aesthetic, psychological, and cultural) that might be thought to be complementary rather than not. Yet they are created as doppelgängers, of themselves or of Schumann, or of socio-cultural attitudes. However, if they are ‘doubles’ of one personality, that personality also includes a Pierrot and a Harlequin. The fragmentation of a cultural construct like self from unitary status culturally after all always fails to reveal only a binary, Indeed, personality is far from that simple – it’s fragmentations stepwise develop into the plenitudes of multitudes and multiple self-representations. For Schumann, this seemed true even of sex/gender binaries – amongst his influences from the past, he considered Beethoven was a masculine, Schubert a feminine force, whilst Bach was everything at once reflecting on itself.

Denk gets it in one here, as he does in his wish that Chernaik could analyse the character of Florestan and Eusebius as musical expression:

Florestan’s characteristic gesture, for instance, is a surge: a crescendo with no corresponding diminuendo. (Schumann’s music is full of these instructions, all in a row; if you took them literally, you would end up playing louder and louder until you or the piano fell apart.) Eusebius’ gesture is the circle: a phrase that bends back on itself or oscillates around a mysterious center. The difference is not just contrast. Some of Schumann’s most compelling music holds these two forces in tension — centrifugal and centripetal, reaching and enfolding. He’s therefore able to tap into two veins of tenderness, one overtly adult-sensual, the second magically on both ends of the child-parent bond — young wonder plus aged reverie. In other words, the masks allow Schumann to capture love as a spectrum: He gets more of it than his fellow Romantics, even Chopin, with whom love can sometimes feel like a performance.

I feel no guilt on relying on Denk here. His expressions in language, though I still need familiarisation with the rich range of meanings, including some technical ones, that he uses. His description seems to me to hum with what I strain to hear in the music and to describe effects at a deeper level than much else I have read. Chernaik does not dive this deep or far, though she hints at the possibility of being able to do so. Again, even from the beginning, Denk gets what Chernaik has to offer correct:

Robert’s life story comes to a harrowing end — I won’t spoil all the grim details, even more tragic than the median Romantic artist’s. Nonetheless, if you take the time to read Judith Chernaik’s new biography, “Schumann: The Faces and the Masks,” your life outlook may improve. Without hitting you over the head, Chernaik allows you to feel the core of Schumann’s story: his love for his wife, Clara, a great concert pianist and formidable muse. Between this and the battle against his own demons to compose truthful music, Schumann’s spirit comes across as an antidote to all the hate and perverse self-love we are forced to swallow in public affairs, day after day.

How forceful and true that last sentence of this review of a biography. But how knotty is Denk further on in his article about how Schumann uses the basic elements of musical making (‘composition’) to develop a novel language of emotions. I don’t fully understand the next quoted paragraph below. It is again much more flighty than anything in Chernaik’s book, but it surely hits upon truth upon how we ought to be learning to talk about our responses to music – one that strikes down into its aim at the neuro-psychological structures of human being:

One of Schumann’s great discoveries was the power of an under-exploited area of the harmonic universe. Imagine a chord Y that “wants” to resolve to another chord, Z. Because music is cleverly recursive, you can always find a third chord (let’s say X) that wants to go to the first: a chord that wants to go to a chord that wants to go to a chord, or — if you will — a desire for a desire. Schumann placed a spotlight on this nook of musical language, back a couple of levels from the thing ultimately craved, deep into the interior of the way harmonies pull at our hearts.

Denk has similarly amazing things to say about Schumann’s experiments with ‘syncopation’, as Chernaik has with issues of counterpoint in music, that all add up to something very grand and very troubling indeed, for they show the depth of our ignorance of how to talk about emotions in depth psychology, even depth neuro-biology. I first came to know Schumann’s reputation from reading Janice Galloway’s wonderful novel Clara (based on the life of Clara Schumann) but I think the fact that he overshadowed the musical genius of his wife still in need of elaboration; his life being more culturally dense and rich still than that she aspired to as a composer,, as she sensed in her (according to Chernaik) constant demands on Schumann to simplify his practice and the demands it made upon audiences. She herself knew that what there was in Schumann was something quite difficult to read because so are life and love, and even the effects of sex / gender binaries.

I loved my exercise in understanding. I intended to continue it by showing what I gained from hearing the music, but I want to be reticent on that. perhaps it will happen later, though I do not know how to express my love of the Symphony in C and the Piano Quintet. But learning happened. i just can’t (or won’t for fear of embarrassment) prove it.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Judith Chernaik (2018: 299-301) SCHUMANN: The Faces and the Masks New York, Knopf Ltd

[2] Ibid: xiii

[3] Jeremy Denk (2018) ‘Robert Schumann: A Hopeless, Brilliant Romantic’ in The New York Times (Nov. 19, 2018) available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/19/books/review/robert-schumann-judith-chernaik-biography.html

One thought on “Beyond ‘genre’, liking and favourites: I think understanding what isn’t already in my culture is my priority : a blog based on Judith Chernaik’s (2018) ‘SCHUMANN: The Faces and the Masks’.”