Currently, I am reading the five volumes of Leonard Woolf’s autobiography. I am on the third crucial volume in which his concern for the oncoming suicide of his wife Virginia is first talked about and explanations that as they increase still don’t suffice to accumulate more than genuine understanding of that tortured, but infinitely great, woman’s true challenges.

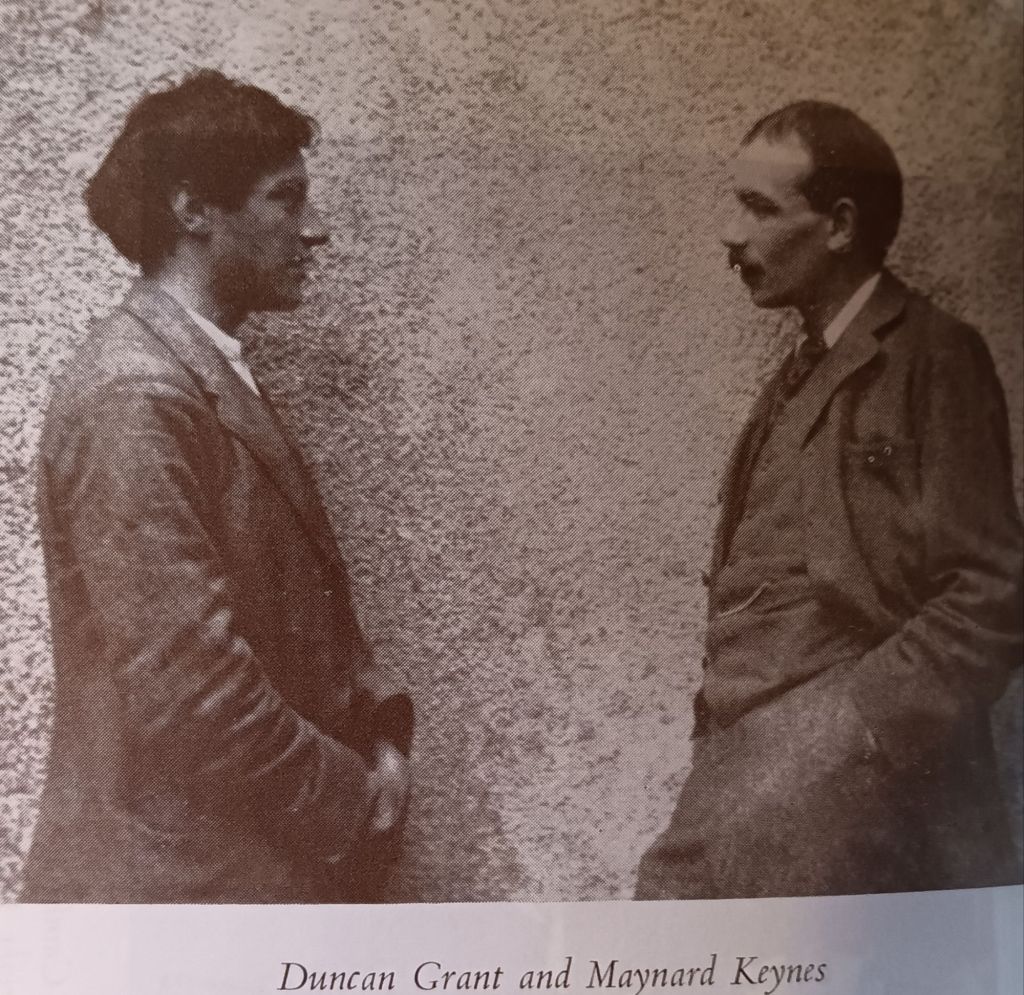

The first volume Sowing: an autobiography of the years 1880 – 1904 takes him up to his heady days in Cambridge and his meeting with a young generation of romantic youths whose softness and pliability in every area of human life haunt him: covering the youth, romantic attractions (at least those for women that Woolf felt able to concentrate upon) and early deaths of Rupert Brooke and Toby Stephen. The youth of soft people haunted him too before clouds gathered: Vanessa and Virginia Stephen, the latter of whom he married without knowledge of the darkness of which her mind was bathed and others who aged EITHER into bohemian irregularity, accepted in artists alone and in privacy like Duncan Grant and Lytton Strachey (alternatively in hiding like Morgan Forster (E.M. Forster)) OR hardened into the establishment at different paces, like Clive Bell and notably John Maynard Keynes. Even in an early photograph from Sowing, Keynes’ queer flightiness seems a much harder version than Duncan Grant’s softly submissive openness, for it might be a crocodile mouth open for prey.

Leonard was 80 when he began his vast project, uncertain how far he would get with his written life (the first volume appearing in 1960-61). The book continually reflects on what he knows now in contrast to life as he sensed and interpreted whilst in his youth. There is a contrast in the prose’s analytic coolness and the heat it allows to simmer under the pacification of resistance to the youth’s original energies. Nevertheless, his view of age generally is a dim one.

For instance, people who expose to the world a gentle softness and vulnerability are ‘sillies’ in his terminology. The term ‘sillies’ is taken from an early translator of Tolstoy, and Leonard thinks it characterises people in Tolstoy’s novels that in Woolf’s eyes to ‘have the streak of the simpleton’, despite the fact they may also be ‘highly intelligent and intellectual’. Tolstoy, Woolf says, thought them the best people in the world’ because they refused to hide their ‘soul’ and let it manifest ‘naked to the world’, unclothed, or in a too soft and transparent covering: ‘wonderfully direct, simple, spiritually unveiled’. He says in a telling moment, preparatory to long discovery of the pain it hides till later chapters: ‘There was something of the ‘silly’ in Virginia, as I always told her and she agreed,…’.

Virginia and Leonard

Woolf at the moment he says this is describing his time at St. Paul’s School where he first developed, ‘the carapace, the facade, which, if our sanity is to survive, we must learn to present to the outside and usually hostile world as a protection ….’. So far, and still at school, so safe. But the ‘carapace’ is not only hard and coarse, it thickens with age, he thinks: ‘This is part of the gradual loss of individuality which happens to nearly everyone, and the hardening of the arteries of the mind which is even more common and deadly than those of the body‘. As an introspective boy, even in teenage, he was ‘half conscious that a mask was forming over my face, a shell over my soul’. But in older age, he has already told us: ‘The facade tends with most people, I suppose, as the years go by, to grow inward so that what began as a protection and screen of the naked soul becomes itself the soul’. [1]

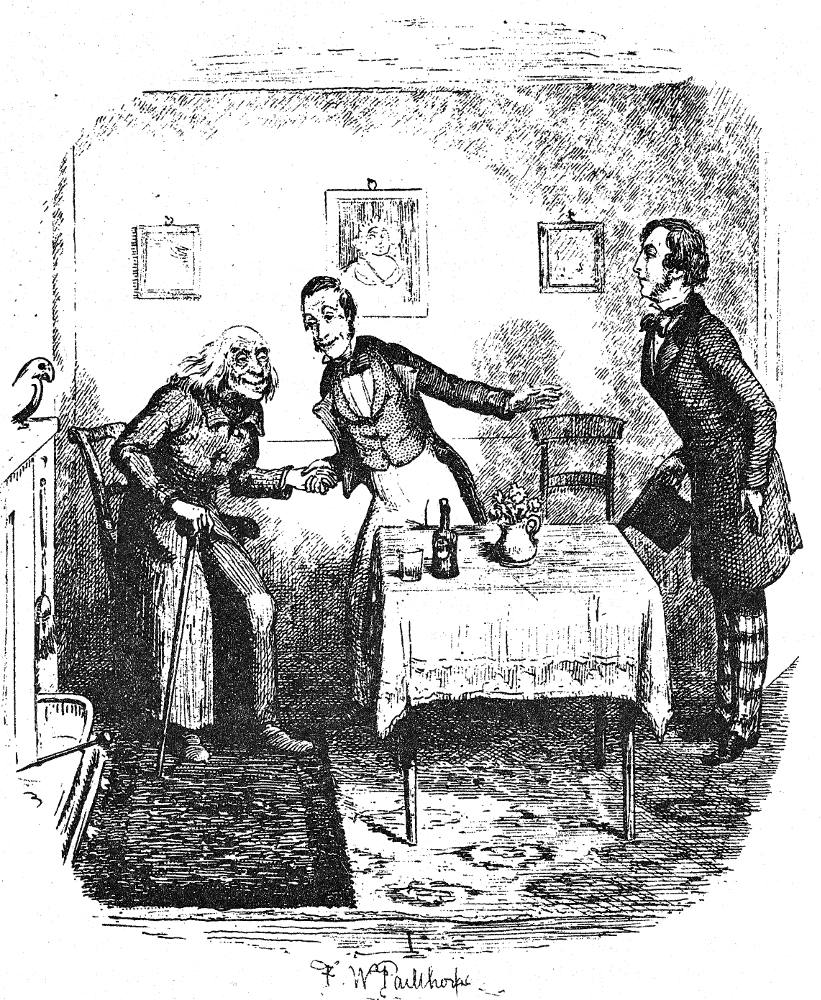

Woolf’s picture of a creeping inward moving hardness of surface, or containing barrier, fits many stereotypes of the aged person, except for those determinatively ‘silly’ in the eyes of others and attracting the patronage they deserve, or so the world tends to think. The ideal exemplar of that silliness unredeemed by intelligence is Wemmick’s Aged P in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, a man for whom the world must be turned into play and for whom hardened souls must soften, in pretence, if they can’t do it in reality as his son, Wemmick Junior, does when released from work role in an office of the corrupt capitalist adventurer, Jaggers.

The aged P is presented by Wemmick, his son, to the heir to a fotune, bound by contract to be known as ‘Pip’.

But modernity throws curved balls at us as we age. Th at is because the concept of age itself ages, or more accurately, metamorphoses in its ideological aspect. Age is now described, helped on by both positive, and lifelong development paradigm, psychologies of the ageing process, as a further adventure in growth and openness, characterised by ‘flow’ and energy, and befogged only by inappropriate stereotypes of what it is like to age. We no longer age gracefully, but age disgracefully fighting stereotypes as we go, and even then, we:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.[2]

Burning and raving is one thing, especially fuelled by alcohol, as Dylan Thomas knew too well. However, the ‘official’ version of modern ageing is worse still because it is neither negative nor an obviously bleak stereotype. It is instead focused on ‘the bright side of life’, claiming the potentialities and powerful wisdoms of later life. It ought to make eldrs feel good, they say. Yet its most dire formulation is the idea of ‘enforced cheerfulness’ that I used to see older people forced to adopt or to present as a mask to carers, both paid and unpaid. This is only another and yet more dangerous carapace, mask or facade than those Leonard Woolf talks about. Perhaps its existence demands some Dylan-Thomas-like burning and raving directed at it, though not necessarily as a result of alcoholic escape. Modernity insists that we elders age with increasing positivism of attitude and temperament and with a view and outlook on the world, and its prospects of futurity in some ideology of ‘growth’, to match.

To these positive codgers everything must look better than once it was, and be driving, even inwardly in our subjective journeys on a path and plan of progress to what is better still. We might hope, on this path only to become an unashamed and deluded Captain Tom, or Uncle Tom, of the aged group; a puppet figure supposedly exemplifying positive attitudes to life whose exploitation will actually be used to mask the dynamics of their greedy successors, intent on changing nothing but the magnitude of their accessible income and control of our lives. Those lives are lessened in their oversimplification and the enforcement of a positive attitude to a world they know is theirs not ours AND over things, about which no one ever should be positive: child poverty, structured progressive inequality, and the active underdevelopment of the skills, knowledge and values of those cultures on its margins. Those lives have no centre on a shared communitarian life, validated as future-worthy

We have been here before. The ones who urge elders to enjoy their diminished role and rejoice in its maintenance by way of a triple lock of patronage are of this kind. Meanwhile, the dispossessed young on the social margins are forced to endure poorer and poorer conditions of work or sustenance and housing of their lives. In truth those same margins eviscerate elders too when they are at intersections of age status with those of stigmatised class, race, sex /gender and sexuality, physical and mental ability, and endurance status.

The passive elder (active only in entitled leisure) which is the ideal but not the reality of of the elder of the future must also bear the weight of an ideology that tells us that their wisdom is or should be, by definition, both politically passive unless persuaded to be the ‘voice’ of a system whose boat refuses to be rocked and, in its word, destabilised (n my word, challenged). Personally, I don’t accept being the voice of the speakers of a greedy exploitative selfish ideology, intent as it is on looking as unlike an ideology as it can, and pretending that illusory pictures of progress and growth are intended to assist everybody.

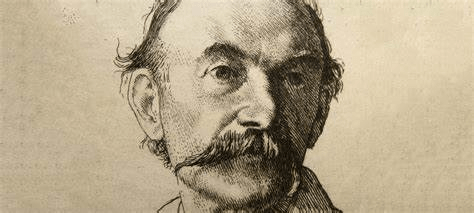

The worst external shell I could devise is that of living in a carapace of blind hope, a really hard shell that pretends to human softness. On the surface of that shell is painted what looks as if it were the soothing shadow of a nuanced humanity. In reality, it is hokum; aimed to divert us from sharp analysis of the true ills of the world. The young doomed poet that was Shelley knew that, but his expression of it feels hopelessly too hopeful and hence lacking. Instead, I look to the echo of Shelley’s poem, Ode to the West Wind, greater comparatively than the predecessor with its faint echo of the master, of course, Thomas Hardy’s In Tenebris II. It is a little known poem with some very well-known lines, often used from Brainyquotes.com. It is also part of a series of poems haunting the shadows of its Latin title. Here it is:

In Tenebris II by Thomas Hardy

When the clouds' swoln bosoms echo back the shouts of the many and strong

That things are all as they best may be, save a few to be right ere long,

And my eyes have not the vision in them to discern what to these is so clear,

The blot seems straightway in me alone; one better he were not here.

The stout upstanders say, All's well with us: ruers have nought to rue!

And what the potent say, so oft, can it fail to be somewhat true?

Breezily go they, breezily come; their dust smokes around their career,

Till I think I am one born out of due time, who has no calling here.

Their dawns bring lusty joys, it seems; their evenings all that is sweet;

Our times are blessed times, they cry: Life shapes it as is most meet,

And nothing is much the matter; there are many smiles to a tear;

Then what is the matter is I, I say. Why should such an one be here?…

Let him in whose ears the low-voiced Best is killed by the clash of the First,

Who holds that if way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst,

Who feels that delight is a delicate growth cramped by crookedness, custom, and fear,

Get him up and be gone as one shaped awry; he disturbs the order here.

The shouts of the ‘many and strong’ (Shelley’s ‘You are many’ in The Ode to the West Wind) seek redress for grievance, and continuing, but sometimes hidden, oppression. The swollen hierarchies over them offer only bland reassurance: ‘That things are all as they best may be, save a few to be right ere long’. Thus, the status quo pleads for its survival before it draws out weapons to enforce its views, if it must, because we fail to conform.

Old men who kick against the pricks of the system that hangs on, Hardy in name if not necessarily in constitution, softly bear the accusation that he is ‘one shaped awry’ and ‘disturbs the order here‘. Such old men either wear the carapace, the shell or facade of softly praising the positive direction in which the privileged try to persuade us that the world us supposedly travelling. An allowable alternative is to bear the inward recognition, to be shared with no-one, that the systems supported are, in fact, a demonstration of the worst possible kind of human unkindness. A world that hides from us the tenacity of its hold of the means for best reproducing and magnifying current inequalities and injustices, forcing aging Ps to ‘make the best of it’ and see what we have as ‘the best of all.possible worlds’, the others being fanciful not possible in their view. The clichés to help you maintain that view abound.

But the old man (or woman for the voice can be female) in In Tenebris II thinks the cataract in their ageing eye stops them seeing, or querying, the supposed BEAUTY and promise of GOOD in the present and its future planned, to its own predispositions, according to claims by those few in whose interests it primarily exists. They think themself wounded by age, convinced by the holders of present power to see and enforce THEIR vision that they are ‘shaped awry’ in the standards of the self-interested and thus are unable to verify what they see as the fruit of wisdom directing their perceptions. What they see, they are told, is a ‘blot’ in their vision that should suggest to them and other individuals who see it, that the vision of the blot is, as it seems, ‘straightway in me alone’. The conclusion is obvious: they are ‘one better’ that they ‘were not here’ at all. Ripeness is not all here but the decay of too long awaited death by one’s successors. However, seasoned by knowledge, strange outdated skills (or so they are called by modernity), those elders are the true rationalists, like he:

Who holds that if way to the Better there be, it exacts a full look at the Worst,

Who feels that delight is a delicate growth cramped by crookedness, custom, and fear,

Meanwhile the ‘stout up-standers’ say that the world is good as it is and on its present trajectory to destruction and they remain powerful (potent) – always their intention: ‘And what the potent say, so oft, can it fail to be somewhat true?’ Why, YES IT CAN fail to be true at all, for it upheld only by the potency of these stout upstanders! Hence I say, even of myself, that: Ageing on its own makes nothing better; if anything, it makes it much more difficult, and in more than one way, ‘harder’ to achieve authenticity as a person aiming for ‘a way to the Better’. Not to look at the disability imposed on the aged by poor social care provision is not to look at the necessary WORST and will never get to ‘the better’ for those worst off. Those that do not see the disenfranchising of the voices of the powerless are in the same position. We all want a ‘a way to the Better’ and lots will vote for it tomorrow, without accounting for the contradictions that comes with it – a dependence on an ideology that says ECONOMIC GROWTH is HUMAN GROWTH, rather than a possible step to animal and vegetable EXTINCTION. They will hear politicians asking them to wait. Hear young people saying that is WISDOM, as I did of Labour politicians in the past,. and praising their own political nous (Twitter’s specialty). But the truth is to wait long for the better will be to bring on the WORST. If we want to ‘find a way to the BETTER’, we better start aiming for the Better pretty soon.

All my love but not that much hope yet

Steven xxxxxxxx

___________________________________________

[1] Leonard Woolf (1962: 55 – 57) – first published 1960 – Sowing: an autobiography of the years 1880 – 1904 London, Readers Union edition at The Hogarth Press.

[2] Dylan Thomas https://poets.org/poem/do-not-go-gentle-good-night

One thought on “Ageing on its own makes nothing better; if anything, it makes it much more difficult, and in more than one way, ‘harder’ to achieve authenticity as a person aiming for ‘a way to the Better’.”