Leonard Woolf in the last volume of his autobiography wittily acknowledges that newspaper critics of earlier volumes had a point when they ‘complained of [his] digressions‘ and attributed it to ‘old age, garrulous senility’. However, he insists that they also missed the main reason for not aiming to ‘force his life and his memories of it into a strictly chronological straight line’. He says: ’If one is to try to record one’s life truthfully, one must aim at getting into the record of it something of the disorderly discontinuity which makes it so absurd, unpredictable, bearable’.[1] There are all kinds of reasons why a straightforward account might be unbearable. Here is a consideration of some of them.

This blog ends with this paragraph. It is the only thing I am sure of in it: “I had to try and say something about Woolf. I do not know if what I have to say is worth saying. But there it’s said! I can breathe again as his books resume their shelf”.

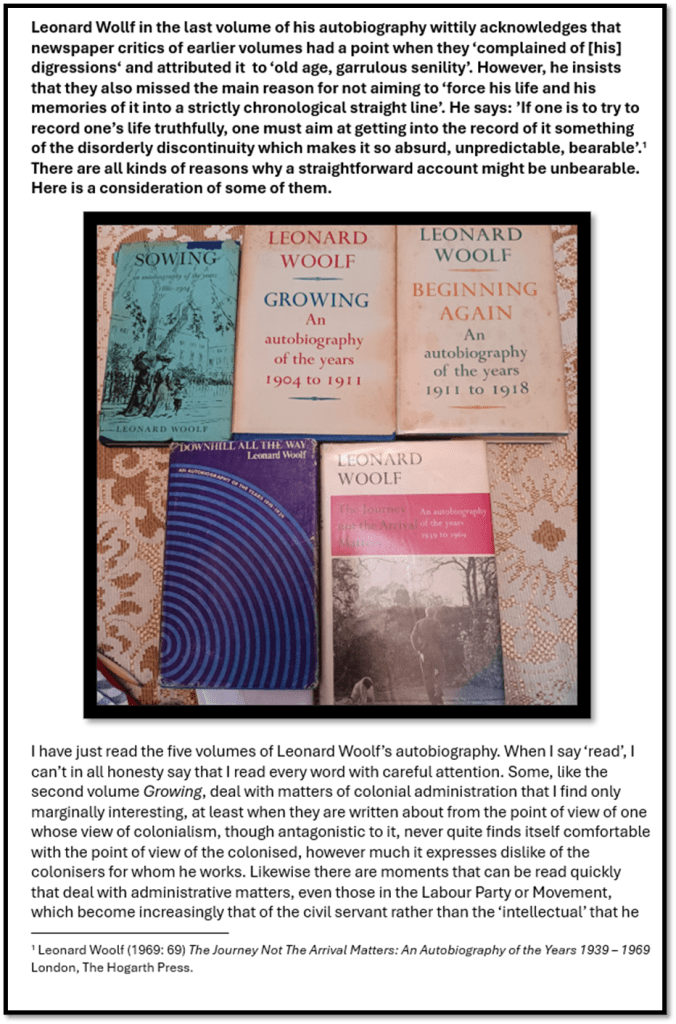

I have just read the five volumes of Leonard Woolf’s autobiography. When I say ‘read’, I can’t in all honesty say that I read every word with careful attention. Some, like the second volume Growing, deal with matters of colonial administration that I find only marginally interesting, at least when they are written about from the point of view of one whose view of colonialism, though antagonistic to it, never quite finds itself comfortable with the point of view of the colonised, however much it expresses dislike of the colonists for whom he works. Likewise there are moments that can be read quickly that deal with administrative matters, even those in the Labour Party or Movement, which become increasingly that of the civil servant rather than the ‘intellectual’ that he professes himself from the very beginning. That doesn’t apply to the sections on publishing and the history of The Hogarth Press, which I find fascinating (although many, I am sure, would not) particularly in relation to the role of John Lehmann, his contempt for whom is palpable.

Yet even when ‘skim-reading’, I came across passages of striking beauty and startling honesty. I think this particularly powerful because the book omits much from the record of pertinent matters that whose effective ‘censorship’ or ‘cancellation’ (if these are allowable words) under these endless other digressions and elaborations I will try to explain in my argument about the peculiarity of this work as a memoir, in my reading of it at least. I dealt with issues of age as I suspected Woolf thought and felt about them illustratively in an early blog (available at this link) that referenced mainly the first volume: Sowing: an autobiography of the years 1880 – 1904

One such beautiful and honest moments in the book is in a sentence that could go unnoticed that I quote in my title: ‘If one is to try to record one’s life truthfully, one must aim at getting into the record of it something of the disorderly discontinuity which makes it so absurd, unpredictable, bearable’.[2] It is typical of Woolf that such a beautiful and rich sentence is also a statement in partial dispute of claims from unnamed reviewers that Woolf’s problem as a writer of memoir is that he writes from the position of ‘old age, garrulous senility’. In my earlier blog I wrote:

Leonard was 80 when he began his vast project, uncertain how far he would get with his written life (the first volume appearing in 1960-61). The book continually reflects on what he knows now in contrast to life as he sensed and interpreted whilst in his youth. There is a contrast in the prose’s analytic coolness and the heat it allows to simmer under the pacification of resistance to the youth’s original energies.[3]

I think I still feel that statement has some truth but less so of the later volumes where the eases of passage between pictures of the present time being recounted by the ongoing memoir are disrupted by transitions to how later events related to these early moments. The final volume, despite the wonderful chapter 1, ‘Virginia’s Death’, seems to fall into the equivalent of notes written up into bland prose thereafter. These include episodically related and rather slanted accounts of single themes (such as the handling of the Hogarth Press’ innovations in publishing) of differing interest and appeal to different readers, whose content has anyway been recounted earlier. We will return to this later for it illustrates the issues of digression in the book better than its better handling in earlier volumes.

But for a moment relish the sentence I pick out wherein he describes his modus operandi as a writer as ‘disorderly continuity’, and claims that this is not only a manner of writing but the nature of life itself: ‘which makes it so absurd, unpredictable, bearable’. That life feels to develop sometimes, perhaps more than we think, absurdly is a matter of fact and partly explained by the unpredictability of some of the unknown consequences of events of which one is less in control than one thinks, or from unforeseen events that change lives, particularly vast global temporal issues like world wars and the death of empires. But if absurdity and unpredictability are clearly already known aspects of the progressions and regressions of time, the issue of making life’s ongoing relentless motion and even the recording thereof, ‘bearable’ is a more problematic matter, that seems cognate to T.S. Eliot’s, whom Woolf – having published The Waste Land, knew as Tom, gnomic evocation of how time requires us to manipulate its potential to malleability in memory to the ends we want to achieve in our present in order to make ‘reality’ bearable’:

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.[4]

This quotation from Jeanette Winterson speaks subtly of itself and for itself

I will return to these more metaphysical questions later. There are four facets of the volumes that I wish to concentrate upon in dealing with how and why one might need to record one’s life in a way that makes its existence ‘bearable; whilst being true to its absurdity and unpredictability. I will deal with these in this order, making the metaphysical question the ultimate one:

- Woolf might want to save others who nevertheless appear in the work from the embarrassment of a revelation in public they would not wish to make or would not have wished to make, in Woolf’s view.

- Woolf might want to justify himself and his career and life decisions in the eyes of readers, especially in the light of known interpretations of those decisions that exist in the public realm and which he disputes.

- Woolf might want to save himself the emotional pain of bearing too much importunate reality, that bears down on him, even in memory with a weight of guilt, fear or hurt.

- Woolf might wish to assert that the nature of both lived lives and memories of them are neither experienced in a strictly linear chronology nor have a simple sequence or directly observable meaning outside of complex intersecting contexts.

I intend to take each of these theses one by one using each as a heading. Some omissions from digressive accounts are voluntary, in others they are less immediately so, reflecting oversimplifications of realities or incentive or unaware of them because they are too painful to face in terms of their implications about one’s own link to humanity. Sometimes they are forgiven as reflecting the ‘thought of the times’, but there is a limit to the latitude of understanding which me might extend. One digression that stands out to me concerns Woolf’s picture of life in the early months of the Second World War. In May 1940, sitting in the garden of Monks House, the Woolf’s and friends, felt that ‘or little private world’ was at threat by the imminent fall of Belgium to Nazi forces, but these feelings of security at threat are connected to ‘a strange, grim, incident that I always in memory connect with them’. He goes on to tell a story concerning a working-class family in the village concerned about the effect on a mother of caring for her disabled son. The essence of this story Woolf says, bad enough in its plain telling,:

… seemed sardonically to fit into a pattern of a private and public world threatened with destruction. The passionate devotion of mothers to imbecile children, which is the pivot of this distressing incident, always seems to me a strange and even disturbing phenomenon. I can see and sympathize with the appeal of helplessness and vulnerability in a very young living creature – … But there is something horrible and repulsive in the slobbering imbecility of a human being.[5]

Try as I might I cannot reconcile this digression with any way in which, though it is admittedly an ‘absurd’ and ‘unpredictable’ intrusion into the narrative of comfortable and privileged lives made less so by war, makes life more ‘bearable’, but that it evokes the contingency on such lives of that it cannot and will not understand, like the horrors of Fascism. This story is entirely unfortunate in that it normalises the eugenic thought that fed into German fascism itself, of the inability of those within the norms of definition of ‘a human being’ of those outside such norms, conveniently labelled ‘imbecile’ or ‘retarded’. The prose itself is stained by its honest description of feelings of horror and repulsion experienced that are not the case Woolf says when one sees an ‘infant puppy, kitten, leopard and even the much less attractive and more savage human baby’. They link these feelings to those caused by the disruption of peace in a garden on the Sussex Downs to the fact that both predicate a world where, once things begin to seem threatened by an ‘ominous and threatening unreality, a feeling that one was living in a bad dream and that one was on the point of waking up from this horrible unreality into a still more horrible reality’. Inevitably the ‘horrible reality’ referred to here has been linked to feelings about the destabilisation of class privilege that one refuses to understand. And, of course, this occurs in the chapter on the forces that led up to Virginia Woolf’s suicide, another ‘horrible reality’ where vulnerability does not lend itself necessarily to empathy for Leonard Woolf that might considerations that might be not ‘bearable’.

At other times the need to make comfortable lives more bearable also exploits the embargo on honesty about certain topics or ways of living one’s life was once greater than it was, especially in relation to the lives of the most marginalised in the social world, and a list of the marginalised conventionally identified follows related to social categories of class, race. ethnicity and culture, sex/gender, sexuality, and differences of physical and mental functioning, as above for that last category. However, it is clearly untrue that these subjects are not discussed or kept under wraps. Indeed, the issue is more complicated in that social discourse about those categories is represented and regulated by norms which function not just to silence the real and diverse voices of marginalised people but supplant it with a voice that is not only a stereotype but one that demeans those who are different from the human norms thought to prevail. This is so even in the case of the colonised where there is a reliance on Eurocentric, and white-privileged, national stereotypy of appalling generalisation as in his sweeping statement in Growing:

The relations between European and some Asiatic peoples are made difficult because the Asiatic does not seem to share the European’s sense of humour. This is not the case with the Sinhalese. They are a humorous people and they have the same kind of humour as the European.[6]

The digressions here are means of evidencing stereotypes, but they are also essentially extremely partial, both in the sense of incomplete and of being biased to a hegemonic viewpoint, that of the entitled white middle-class male. This is complicatedly also the case in Thesis One.

THESIS ONE: Woolf might want to save others who nevertheless appear in the work from the embarrassment of a revelation in public they would not wish to make or would not have wished to make, in Woolf’s view.

There are plentiful instances in the full autobiography that involve moments when the narrative chooses not to explore some sub-narrative. Again they deal with topics and persons, the fullness of which must not be exposed in public because they disturb the order and peace of a society privileging the few. As in the case of the most vulnerable of people in society such as learning disabled people, we have seen that Woolf colludes in pushing their visibility under an understandable, or so he thinks, desire to hide them the perceived reality of those without experience of the comprehensive range of human experience. Life is more ‘bearable’ if such realities are hidden, those involving divergence from comfortable norms. Yet Woolf outside of this book must have faced such realities in the experience of Virginia’s psychotic episodes, though he often tries to hide them under poor psychiatric labels. Whether he accepted these is more difficult to ponder. I think though that it makes the very difficult life experienced in giving care to people with psychosis seem easier sometimes – in that it explains away horrible realities. But the same issues around the subject of other marginalised lives – especially queer sexualities.

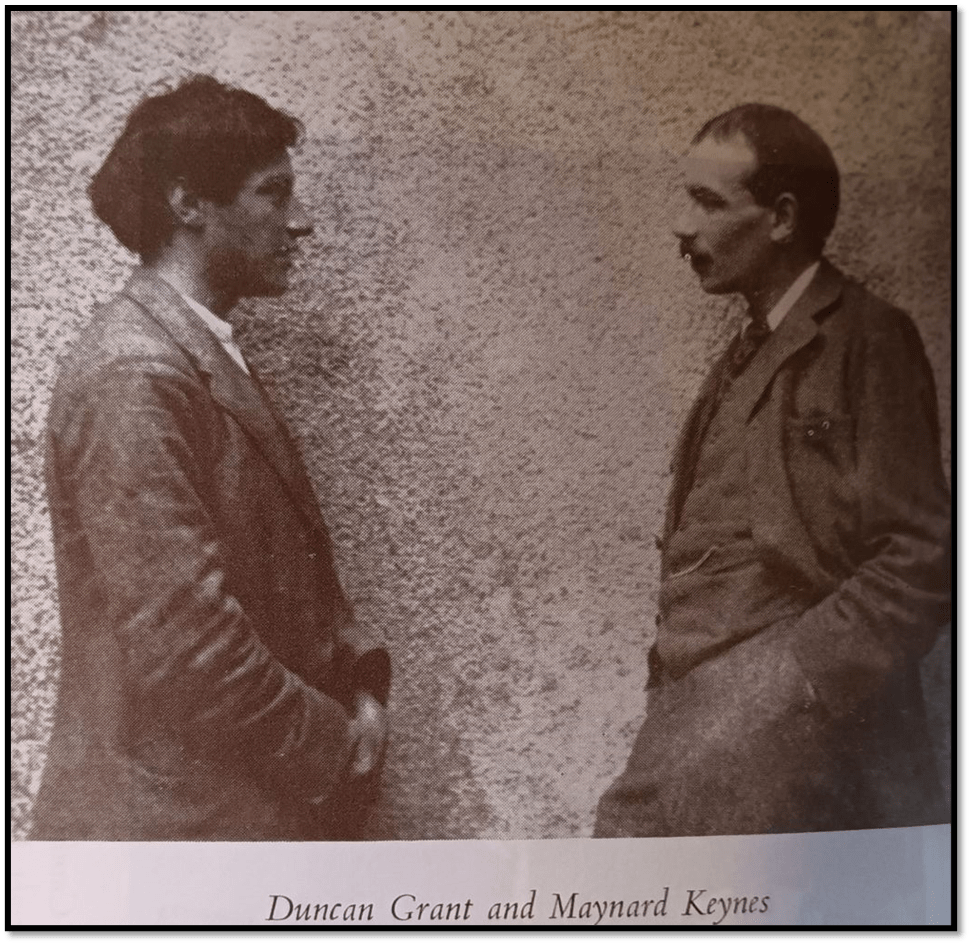

And much effort must have put into this book to exclude these, or never to explore them in either the books’ main or digressive narratives. This is surely the case in terms of Virginia Woolf’s queerness and the relationship between her and Vita Sackville-West but is too in terms of the absence of consideration, except in terms of their heterosexual partners of Duncan Grant, Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey, Morgan Forster, and Stephen Spender.

This must have been a conscious decision in dealing with Leonard’s experience of friends in Cambridge, for it is clear that Woolf was aware of the propensity even of very young boys to experiment in thought and even bodily in sexual relationships in a boys public school. Schooled at Arlington House until he went to St. Pauls School and from the age of 12 at Kemp Town, Brighton he records that the only thing he ‘learned thoroughly … was the nature and problems of sex’’. He is not ‘prudish’, he insists but says that he has:

… never known anything like the nastiness – corruption is not too strong a word – of the minds and even to some extent bodies of the little boys in Arlington house when I first went there.[7]

There is some exaggerated language here to describe the sexual curiosity of young boys, that does not fit with the Woolfs’ regular use, alongside the people mentioned when referring to themselves, to close friends like Strachey, Keynes and Grant as ‘buggers’. Likewise Woolf never identifies John Lehmann’s sexuality though it was sufficiently public. My own take on this is that it causes his accounts to be skewed to the maintenance of privileged accounts of the world that he refuses to perturb, in the interests of the status quo. For John Lehmann, who I will mention Thesis TWO was promoting the publication of marginalised voices, including queer voices like his own (such as the American Paul Bowles and the Englishman, Ernest Frost, in John Lehmann Press precisely because he could not do so partnered with Woolf in The Hogarth Press.

THESIS TWO: Woolf might want to justify himself and his career and life decisions in the eyes of readers, especially in the light of known interpretations of those decisions that exist in the public realm and which he disputes.

The debate with John Lehmann in the last volume regarding the Hogarth Press is geared to correcting a notion that Woolf was not, being an intellectual, a serious man of business. It is thus he treats Lehmann in relation to the latter’s wish to expand the list of writers published by The Hogarth Press. Woolf presents their argument in terms of his distrust of the economics of ‘expansion’ and Lehmann’s advocacy of it. Hence his long 30-page chapter length digression on ‘The Hogarth Press’ in his last volume seems entirely fuelled by the fact that Woolf wants to rescue his reputation in terms of his control over Hogarth Press. He cites John Lehmann’s account (in the second volume of the latter’s biography) of his split with Woolf twice, but insists that Lehmann misunderstands how large-business methods relate to books as a commodity, in comparison in his analogy, to bars of soap. But books, especially literary books, cannot sustain the wait that publishers have before those books are truly discovered to be what they are Hence, says Woolf: ‘It is not surprising that very few of these small, “expanding” publishing businesses survive’.[8] To rub salt in the wound he instances later that Lehmann’s independent venture fell foul of this very lesson he refused to learn from Woolf. His instancing that John Lehmann Ltd folded in 1952 is an ad hominem attack asserting that Lehmann ‘is too certain that he is right and the other fellow (even Leonard Woolf) is wrong – a dangerous generalization’.[9]

But Woolf’s digression on Lehmann really fails to explain, as Lehmann does round and about the bits of his autobiography quoted by Woolf but excluding this, that Lehmann’s ambition as a publisher and editor was the revival of literature through the voices of the marginalised writers which Woolf did not want to support. Lehmann makes it clear that he felt Woolf was loath to support new writing and young writing and drawing reproduced in photogravure that would rival the reputation of Paris and foster ’the new flowering of the romantic, visionary tradition of English painting’, associated, as it happens with queer artists John Minton and Keith Vaughan.[10] In a later volume of his autobiography (1966) , which we do not know if Woolf read, Lehmann cites the kind of new voices he introduced through his venture – Robin Jenkins, still highly prized in Scotland though ill-known in England, Ernest Frost (an openly queer writer), Percy Coates, a Yorkshire miner, and Roland Camberton – now forgotten except by Iaian Sinclair, who learned from him, who wrote of working-class life in London, what Lehmann calls ‘the low life of Soho and the East End long before it became fashionable’.[11] The chapter on The Hogarth Press in Woolf ends with an even sharper attack on Lehmann. The terms of the attack are those of a comparison between how a publishing venture and new writers relate to each other.

There is no reason to believe that it is impossible that tomorrow or tomorrow or tomorrow there may not be a circle of young, unknown, brilliant writers whom someone might begin to publish on a small scale as we did in 1917.

Yet such a venture can only succeed Woolf says of any future contender:

Provided he is a good businessman and is determined to limit his operations, refusing to listen to the John Lehmanns singing their siren song about expansion which can lure one so easily on to the Scylla of the take-over or the Charybdis of bankruptcy.[12]

It seems to me here that the factor against which Woolf sets himself in Lehmann is not the foolish nature of his business sense but his insistence that a Renaissance of ‘young’ writers must not confine itself to ‘a circle … of brilliant writers’ appropriate to small scale launching, such as Bloomsbury was (the very smallest of circles – even if open to people like Tom Eliot to prove himself) not searching the wider margins important to Lehmann that included new voices saying new things and challenging the values of an older regime. That John Lehmann is cast as a female siren that can ‘lure’ men like Odysseus and Woolf onto the rocks seems to me significant. Yet again, Wollf uses digression to limit the world of the intellectual to those who no longer challenge the status quo.

THESIS THREE: Woolf might want to save himself the emotional pain of bearing too much importunate reality, that bears down on him, even in memory with a weight of guilt, fear or hurt.

Thus far I have been fairly negative about Woolf’s digressions, though I apply that only to him as a writer not to the man who was obviously infinitely more complex. They cover over the limitations of his world-view: they reproduce stereotypes of the colonized and those disabled by values that exclude certain ways of living that requires external support. However, I strongly believe that digression has a psychological function for Woolf that is less political than that, though he feeds into that politics of not exposing oneself to that which disturbs and destabilises. In the third volume of the autobiography, Beginning Again, he compares his thoughts about financial insecurity to the panic states experienced sometimes by Virginia. Mentioning his contrasting lack of worry about ‘material things’, he digresses into the need to tell a truth about himself (in fact one he had already shared in Sowing):

… I must admit that I am, I think, a psychological worrier at the back of my mind, in the depths of my soul, or in the pit of my stomach (probably all three). I have always felt psychologically insecure. I am afraid of making a fool of myself, of my first day at school, of going out to dinner, or of a weekend at Garsington with the Morrells. What shall I say to … Lady Ottoline Morrell, or Aldous Huxley. My hand trembles at the thought of it, and so do my soul, heart, stomach. Of course, I have learnt to conceal everything, except the trembling hand: ….[13]

No doubt Garsington could be a fearful place, though records of it in D.H. Lawrence seem to make it seem rather silly. It certainly hosted the great and good and there is clearly here an admission that Woolf often felt out of his depth socially and emotionally in a way that registers viscerally and outwardly in his body. The passage recalls that I wrote about in an earlier blog, from Sowing, where Leonard speaks of the fear of souls being ‘naked’, without cover. He is my paragraph where he says that in his time at St. Paul’s School he first developed :

… ‘the carapace, the facade, which, if our sanity is to survive, we must learn to present to the outside and usually hostile world as a protection ….’. So far, and still at school, so safe. But the ‘carapace’ is not only hard and coarse, it thickens with age, he thinks: ‘This is part of the gradual loss of individuality which happens to nearly everyone, and the hardening of the arteries of the mind which is even more common and deadly than those of the body‘. As an introspective boy, even in teenage, he was ‘half conscious that a mask was forming over my face, a shell over my soul’. But in older age, he has already told us: ‘The facade tends with most people, I suppose, as the years go by, to grow inward so that what began as a protection and screen of the naked soul becomes itself the soul’.[14]

The use of digression and indeed of projection of later events from earlier ones, equally prominent in these books, are, in my view facets of carapace building, of having ‘learnt to conceal things’ and hardening the arteries of the mind. They appear to control the very time that poses itself as an enemy in expectations and fears, that feed each other, of making ‘a fool of’ yourself or being found inadequate. They act defensively, as I have tried to show the one on the Hogarth Press does to knock down one’s assailant before he does you. In most of the book, they enter as long narratives, sometimes of doubtful or trivial relevance, to hold back the moment of narrating matters that cause pain or deflecting that pain. They make life ‘bearable’ that is just as the absurdities of the unpredictable fall on you.

You have when you narrate to predict as if you had at the time, to sop the recurrence of an originating pain and anxiety. You have to digress to delay an encounter, with Ottoline Morrell or the story again of Virginia Woolf’s flight and death in the Ouse. Hence the long story about the life of the female friend and doctor trusted by Virginia and consulted near the time of her suicide. The long story of Octavia Wilberforce and her partner, Elizabeth, enters as he begins to show his uneasiness about Virginia’s state of mind and delays the narrative of that story for eight pages, whilst we return to happier times listening to Elizabeth’s ’old tales of (her) youth poetically, romantically’. During such convoluted digressions we regress to a time wherein: ‘Virginia and I were entranced by this saga’. For Woolf, the function of digressive story-telling is to gain control of that of which you felt you little or no control, such as his wife’s suicide, and thus render it ‘bearable’, however absurd and, at the time ‘unpredictable’ it also remains.

THESIS FOUR: Woolf might wish to assert that the nature of both lived lives and memories of them are neither experienced in a strictly linear chronology nor have a simple sequence or directly observable meaning outside of complex intersecting contexts.

The title of Woolf’s fifth volume, The Journey Not The Arrival Matters, is a quotation that is often in popular culture attributed to T.S. Eliot, although these words cannot be found in him. Woolf attributes it directly to the philosopher Montaigne, ‘the first civilized modern man’ though he can only say of its attribution that he ‘says somewhere’ these words, or their equivalent in French.[15] Of course, as far as the autobiography is concerned, its aim is to show that Woolf is not measuring the value of either his life and its record by that place in space and time to which it arrives but to the process of travelling. To prioritise a journey over its beginning and end is certainly pertinent to T.S. Eliot however and like him, I think Woolf is attempting a metaphysics of time, in part at least, in his autobiography, arguing that time is only the experience of transit not a fixed place, and showing that memory can travel both back, in a regression, or forward, over that journey in memory. I have tried to argue this has therapeutic value for Woolf in controlling the Apparent onward progress of time that cannot be stopped as you initially experience it but can in its recall and manipulation, to make it ‘bearable’.

But this is a very different proposition to the belief that there is no common sense way in which the ends and beginning of a process can be discerned. Woolf’s attachment throughout the biography to the thought of G.E. Moore would have rejected the philosophical idealism that made F.H. Bradley, a key influence on Eliot, to say that Time and Space were unreal. But he would have empathised with the idea that to say anything true would involve an endless iteration of qualifications and qualifications of those qualifications, a point he laughs at in Moore in Beginning Again. A journey that regresses is as significant as one that progresses. As he says of Moore there: Talking to him one lived under the shadow of the eternal, though silent question: “exactly what do you mean by that?”’[16] The issue is not that there is no end or beginning or that your beginning is your end or vice-versa, as in Eliot’s Idealist Christian patterns of redemption but that, although you know with Moore that every question may be answered, how it may be answered without endless digressions in the journey is far from certain.

Earlier I quoted Eliot in Burnt Norton saying:

Go, go, go, said the bird: human kind

Cannot bear very much reality.

Time past and time future

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.[17]

I think Leonard is a rather plainer man. He knows he cannot bear ‘very much reality’ and shows it both consciously and unconsciously in the circling patterns in time in his autobiography, but he has no truck with the vague metaphysic of time at the end of that quotation. Rather, he must ‘bear what has been’ not by replacing it with counterfactual possibilities but by hiding under the shell of a mask he constructs by the manipulation of narrative time. The problem is that though a reader may see Woolf as having escaped his neurosis, Woolf can still see himself under the mask. And few will penetrate the mask to find him. He did find one such person, Sigmund Freud, whom he published in English translation and whom he met in conversation, later saying of that meeting:

There are few things more unexpected and more exciting than suddenly finding someone of intelligence and understanding who at once with complete frankness will go with one below what is the usual surface of conversation and discussion[18]

I wonder how Leonard looked to Sigmund under the surface upon which neither wanted to float like the mere top of a huge iceberg.

I had to try and say something about Woolf. I do not know if what I have to say is worth saying. But there it’s said! I can breathe again as his books resume their shelf.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Leonard Woolf (1969: 69) The Journey Not The Arrival Matters: An Autobiography of the Years 1939 – 1969 London, The Hogarth Press.

[2] Leonard Woolf (1969: 69) The Journey Not The Arrival Matters: An Autobiography of the Years 1939 – 1969 London, The Hogarth Press.

[3] https://livesteven.com/2024/07/03/ageing-on-its-own-makes-nothing-better-if-anything-it-makes-it-much-more-difficult-and-in-more-than-one-way-harder-to-achieve-authenticity-as-a-person-aiming-for-a-way-to-the-better/

[4] T.S. Eliot from ‘Burnt Norton’ in The Four Quartets. It is available at: https://genius.com/Ts-eliot-four-quartets-burnt-norton-annotated

[5] Leonard Woolf 1969 op.cit: 51f.

[6] Leonard Woolf (1967: 242) Growing: An Autobiography of the Years 1904 to 1911 London, The Hogarth Press

[7] Leonard Woolf (1962 Readers Union version: 52) Sowing: An Autobiography of the Years 1880 to 1904 London, The Hogarth Press

[8] Leonard Woolf (1969: 110) The Journey Not The Arrival Matters: An Autobiography of the Years 1939 – 1969 London, The Hogarth Press.

[9] Ibid: 114

[10] John Lehmann (1960: 312) I Am My Brother: Autobiography II, London, Longmans. Woolf quotes from page 314 of this book where only the business future of the Press might seem to be involved.

[11] John Lehmann (1966: 172) The Ample Proposition: Autobiography III, London, Eyre & Spottiswoode.

[12] John Lehmann 1960 op.cit: 126

[13] Leonard Woolf (1964: 91) Beginning Again: An Autobiography of the Years 1911 – 1918 London, The Hogarth Press.

[14] Citing Leonard Woolf (1962: 55 – 57) – first published 1960 – Sowing: an autobiography of the years 1880 – 1904 London, Readers Union edition at The Hogarth Press in https://livesteven.com/2024/07/03/ageing-on-its-own-makes-nothing-better-if-anything-it-makes-it-much-more-difficult-and-in-more-than-one-way-harder-to-achieve-authenticity-as-a-person-aiming-for-a-way-to-the-better/

[15] Leonard Woolf 1969 op.cit: 172

[16] Leonard Woolf 1964 op.cit: 41

[17] T.S. Eliot from ‘Burnt Norton’ in The Four Quartets. It is available at: https://genius.com/Ts-eliot-four-quartets-burnt-norton-annotated

[18] Ibid: 168