A claim of being ‘passionate’ about something often comes with an apology these days. Passionate people don’t just talk to you. The ‘go off on one’ in the modern term. They seem forced to act or talk in ways that go beyond people’s expectations of them, or indeed anyone. Those people often include the person who is said to be passionate. The issue is – is it a problem not to be in control of your feelings and actions? Certainly, the Attic Greeks felt so if you go by their tragedies and consider the ‘passions’ of Oedipus.

On the other hand we tell ourselves or others not to apologise for being ‘passionate’, because ‘it shows you are human’. And indeed the issue of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often debated in terms of the dangers of being over-rational in one’s decision-making. Both Ian McEwan and Kazuo Ishiguro have written about this issue, the latter in a very wonderful novel on which I’ve blogged (at this link), Klara and The Sun. When I was young, people talked a lot about not having feelings as a symptom, as a disassociative state. Some people say that they can not have feelings, like Caleb interviewed by David Robson in 2015 for the BBC (Online). That interview was the basis of a discussion of the possible neuroscience underlying the ‘condition’ called alexythimia. I waver at using this word ‘condition’ for it may be just an instance of neurodiversity, that is reified in having the label “alexithymia”, which some of those people labelled thus embrace, and abbreviate it into a norm to describe themselves: ‘alexes’.

In fact, Caleb claims not to feel almost any emotions – good, or bad. I meet him through an internet forum for people with “alexithymia” – a kind of emotional “colour-blindness” that prevents them from perceiving or expressing the many shades of feeling that normally embellish our lives. The condition is found in around 50% of people with autism, but many “alexes” (as they call themselves) such as Caleb do not show any other autistic traits such as compulsive or repetitive behaviour.

Picture from: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20150818-what-is-it-like-to-have-never-felt-an-emotion

Hence, you cannot win if you wish to avoid being labelled, can you! You may be considered over-passionate, about a thing or subject, or even generally, or in deficit of passion to things you OUGHT to have feelings about, as others judge the expected norms, or generally.

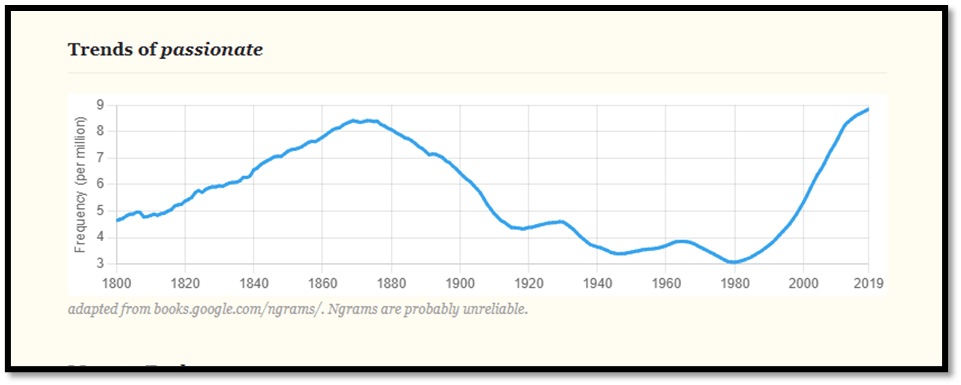

Maybe, as always, we need to consider whether ‘passion’ is not a thing of nature but of human social construction. Though n-grams are considered far from valid as evidence for a number of reasons, they can be used to show, with a pinch of salt necessarily added, that the textual canons used by Google, show historical variation in its frequency of usage. What still needs explanation is the rise in the frequency of use of the word from 1980. Hmm!

From: https://www.etymonline.com/word/passion

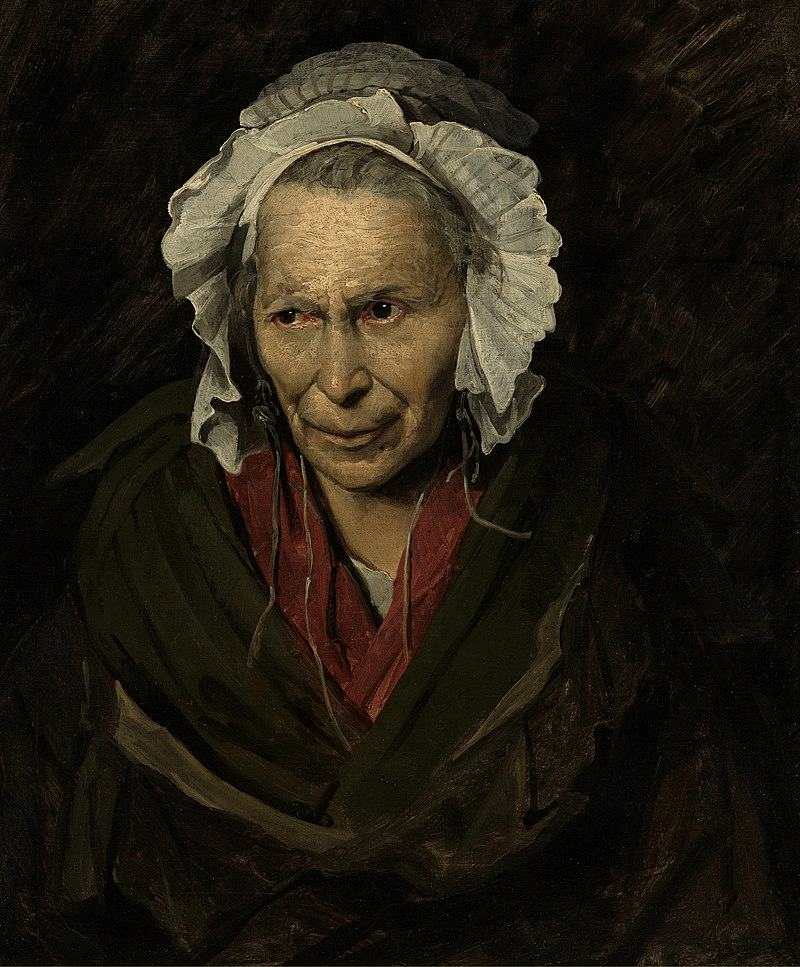

It is clearly possible to argue why there is a peak of popularity of the word in the 1850s to the 1890s. Its meaning then match a kind of favour given to an extreme kind of interest in ‘passion’ as a trait of human behaviour, seen as different from norms and averages and sometimes decried and other times praised. In Victorian psychological medicine, it was possible to describe the ‘psychological condition’ of singularly demarcated extreme passion (envy, lust, or son) about a thing, person, or state of society as a monomania. The definition in Wikipedia is good: ‘a form of partial insanity conceived as single psychological obsession in an otherwise sound mind‘. The term’s equivalent in French was used by Théodore Géricault to label his wonderful portraits of psychiatric patients.Here, for instance is ‘envy’, unsurprisingly, for the period, typified as a female trait:

Théodore Géricault (1822) La Monomane de l’envie

In England the term was popularised amongst poets by the now forgotten Bryan Waller Procter who served as a Commissioner in Lunacy after the passing of The Lunacy Act in 1845. His pseudonym as a poet was Barry Cornwall, and he was known to poets Romantic and Victorian, right up to Thomas Hardy (think of Tess of the D’Urbervilles), through his dramas and Dramatic Sketches, influencing their subjects and sometimes style. His influence is felt in monologues especially deemed to come from monomaniacs like many of those of Robert Browning: The Bishop Orders His Tomb at St. Praxed’s, My Last Duchess, and Porphyria’s Lover. Tennyson’s study of his own suicidality is implied in his poetry from an early age, making links between monomania and the early understanding of schizophrenia in The Two Voices and notably in his 1855 work, Maud: A Monodrama (the title is significant in recalling monomania as A. S. Byatt has argued).[1]

So to the question, ‘What am I passionate about?’, I feel I need to tread with caution here and cover my tracks with definitions and etymologies. Wikipedia traces the word in its reference to emotion to the Greek for the Latin below it transliterates the Greek: ‘πάσχω “to suffer, to be acted on” and Late Latin (chiefly Christian) passio “passion; suffering”.

Etymonline is more specific about the post Latin stage without reference to the Greek usage, and thus more concentrated on the Western Christian tradition (Greek being the Byzantine Orthodox route) starting with their line of influence from Latin Christian vocabulary:

They continue the story in notes in prose:

c. 1200, “the sufferings of Christ on the Cross; the death of Christ,” from Old French passion “Christ’s passion, physical suffering” (10c.), from Late Latin passionem (nominative passio) “suffering, enduring,” from past-participle stem of Latin pati “to endure, undergo, experience,” a word of uncertain origin. The notion is “that which must be endured.”

The sense was extended to the sufferings of martyrs, and suffering and pain generally, by early 13c. It replaced Old English þolung (used in glosses to render Latin passio), literally “suffering,” from þolian (v.) “to endure.” In Middle English also sometimes “the state of being affected or acted upon by something external” (late 14c., compare passive).

In Middle English also “an ailment, disease, affliction;” also “an emotion, desire, inclination, feeling; desire to sin considered as an affliction” (mid-13c.). The specific meaning “intense or vehement emotion or desire” is attested from late 14c., from Late Latin use of passio to render Greek pathos “suffering,” also “feeling, emotion.” The specific sense of “sexual love” is attested by 1580s, but the word has been used of any lasting, controlling emotion (zeal; grief, sorrow; rage, anger; hope, joy). The meaning “strong liking, enthusiasm, predilection” is from 1630s; that of “object of great admiration or desire” is by 1732.

As compared with affection, the distinctive mark of passion is that it masters the mind, so that the person becomes seemingly its subject or its passive instrument, while an affection, though moving, affecting, or influencing one, still leaves him his self-control. The secondary meanings of the two words keep this difference. [Century Dictionary]

I was surprised that the reference to Century Dictionary was not particularised and dated for it refers to a specific late nineteenth-century text from the USA: The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language, 6 vol. (1889–91). [2] That Dictionary’s definition is part of the history of the word ‘passion’s’ reference to the ongoing social construction and reconstruction of the word. In later history it is transformed from its use in references to Christ’s PASSION (His enforced death on the cross and the suffering endured) to more generalised Christian experience, even declining from the martyrs and saints to everyday Christians. Thence, it passes into secular uses to denote a specific psychological trait, like unto Christian passion.

We arrive at the idea of ‘passion’ as a compulsion: the stuff of a disordered self wherein with regard to being moved, affected (to the point of expression thereof of these things as a poet does), or influenced to action, ‘the person becomes seemingly’ [passion’s] ‘subject or its passive instrument’. The issue of a strong belief in the autonomy and free will of the individual, so necessary to the construction of American ideology, of self-making and self-control, is dominant here.

However the American turn itself feeds off the European Enlightenment, as Tom Paine did. Here is Denis Diderot (1713–1784), the eighteenth century Encyclopedist and rationalist, as cited in Wikipedia, describing ‘passions’ as (with my emphases in italics):

penchants, inclinations, desires and aversions carried to a certain degree of intensity, combined with an indistinct sensation of pleasure or pain, occasioned or accompanied by some irregular movement of the blood and animal spirits, are what we call passions. They can be so strong as to inhibit all practice of personal freedom, a state in which the soul is in some sense rendered passive; whence the name passions. This inclination or so-called disposition of the soul, is born of the opinion we hold that a great good or a great evil is contained in an object which in and of itself arouses passion.

When Wikipedia instances the last of the great rationalists, now himself fading from fashion, George Bernard Shaw, the world of the intellect is declared to have a power that displaces religion with its own force: “intellectual passion, mathematical passion, passion for discovery and exploration: the mightiest of all passions'”. The belief in a rational independent passion in Shaw has since then fought with one that has seen it as derived from strong unconscious forces described differently and attributed with values in different ways by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung. For Freud there is, in Wikipedia’s words, ‘a continuity (not a contrast) between the two, physical and intellectual’ and they instance how Freud ‘commended the way Leonardo da Vinci “had energetically sublimated his sexual passions into the passion for independent scientific research”. Jung would have invoked grander principles than sexual ones but they had their root too in the relationship of a child’s desire for autonomy and the continuing felt force of psychic Forces, especially the Animus and Anima, hitherto confused with gods but certainly the stuff of ‘Higher Powers, such as those Alcoholics Anonymous adopted from him.

In the world of work currently, passion is seen as sometimes a benefit though rarely so. That is because it is also confuted with the inability to take direction from ‘lesser’ sources, like line-managers, and with failures to see objectively and without being ‘driven’ by the imagination. The whole complex nuance of the ‘drives’ becomes implicated in this situation.

So here we are. What am I passionate about? I think I am passionate about everything that seeks release from an oversimplified egotism and narcissism but which is not therefore without consequences to self-making and change. Hence, the link for me between the many voices in literature, art, and politics to the drive towards the communitarian values that are also liberatory of forces that serve others. Communitarian values attempt to achieve a self that has intrinsic connections to empathy and altruism, so missing from the ethos of capitalism and hierarchical patriarchy. In the latter, ‘ownership’ and ‘control’ have taken precedence over the shared and the aspirational nature of communal learning. It is all about learning and hence why I blog in honour to the continuity of learning and sharing it.

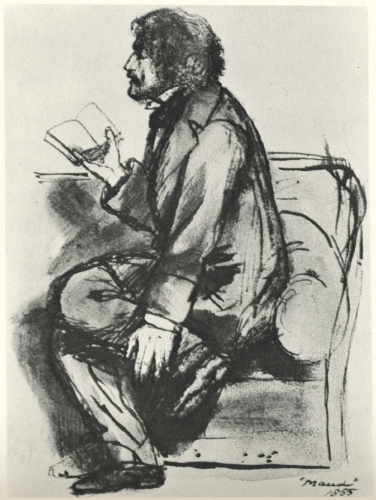

I have to admit that this is a stance with contradictions; for my tendency is to take things too far, get carried away, like all ‘passionates’. Such persons often become very lonely people indeed, locked in monomania fearful of the ‘cold and clear cut face’ of the world around them, seeking an instance from it to love them, like Tennyson’s monomaniac in Maud. That he saw this cold and clear-cut face as ‘Womanlike’ may well have more to do with the mistakes and rooted cultural misogyny that even queer people make and the danger of all binaries that makes what persecutes you the not-understood Other. It tends to see the negative term in conventional binaries that it equates with a ‘thing’ so ‘passionless’ in your construction of it that it excoriates your passion or forces you to do so. When Dante Gabriel Rossetti captures the elder poet reading Maud, Tennyson seems to be holding himself in, capturing his foot from the flight it might otherwise take from all norms:

Cold and clear-cut face, why come you so cruelly meek,

Breaking a slumber in which all spleenful folly was drown'd,

Pale with the golden beam of an eyelash dead on the cheek,

Passionless, pale, cold face, star-sweet on a gloom profound;

Womanlike, taking revenge too deep for a transient wrong

Done but in thought to your beauty, and ever as pale as before

Growing and fading and growing upon me without a sound.

Luminous, gemlike, ghostlike, deathlike, half the night long

Growing and fading and growing, till I could bear it no more.

But arose, and all by myself in my own dark garden ground,

Listening now to the tide in its broad-flung shipwrecking roar,

Now to the scream of a madden'd beach dragg'd down by the wave,

Walk'd in a wintry wind by a ghastly glimmer, and found

The shining daffodil dead, and Orion low in his grave.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

__________________________________________

(1} For The Two Voices see: https://genius.com/Alfred-lord-tennyson-the-two-voices-annotated and for Maud, see https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/56913/pg56913-images.html.For A.S.Byatt summarised see: https://victorianweb.org/authors/tennyson/kincaid/ch6.html.

[2] For more information see: https://www.britannica.com/topic/The-Century-Dictionary-An-Encyclopedic-Lexicon-of-the-English-Language