Erich Fromm distinguishes a healthy culture of ‘being’ from the diseased cultures obsessed by ‘having it all’. However you define ‘all’ in that phrase, it is the acme of a diseased culture ruled by individual greed alone.

The psychoanalyst Erich Fromm was an iconoclast of amd from many traditions in which he was nevertheless embedded, the key one being a deep immersion in Jewish Rabbinical texts, from which he spun a beautiful democratic socialist theory of being. He was deeply antagonistic to the ‘brave new world’ of capitalism in the USA, of which he was a citizen, believing in but redefining its bounding tenets of individual freedom and moral choice. Andreas Matthias, in an online essay, defines a basic tenet of Fromm’s philosophy thus:

Erich Fromm distinguishes between two modes of existence. One can live one’s life in the “mode of having” or in the “mode of being”. The mode of having sees everything as a possession, while in the mode of being we perceive ourselves as the carriers of properties and abilities, rather than the consumers of things.

This is a sound base from which to query both whether ‘having it all’ is an idea that is a sound goal for human beings and whether, anyway, it references human desires or other states of feeling conducive to the holistic health and well-being of any one of those beings. To move from definition as a human ‘being’ to a human ‘having’ is, after all, what is at stake here, whatever our pursuit of things that we may OWN and POSSESS. I say the latter because it is sometimes thought that its okay to want to have things as long as the things you want are not evaluated by their exchange value. Those people who say that instance things like love, family, health and other abstractions from felt experience. But there are two flaws in this argument:

- First, commodification turns abstracts into things (reifying them) that can be either possessed or have exchange value for other possessions; an operation at the base of capitalism. Since capitalism’s onset, fakery and /or advertising has claimed, for instance, that certain medications, or processes (applied by an expert and qualified practitioner worthy of pay) could, at a cost, guarantee life, psychological well-being, or health, or failing that the appearance of having any of those. The notion that you can HAVE health and well-being as solely yours is intensely related to being able to BUY those things, as if they were objects independent of a person’s conditions of social like.

- Second, whatever one HAS is subject to the contingency of loss like all things that we claim to OWN. You may have something, but you have to go to some lengths to sustain it from loss by theft, necessities trighered during the process of living, or the decay endemic to time. That, in brief, is why you can not HAVE health or well-being, for they are not yours to keep and never were. The causes of individual health and well-being are not and never can be those controlled entirely by an individual without the participation of others, contributing to many other causes of one’s well-being and health. They can help destroy the latter should they merely wish or by necessity by virtue of being part of how the instabilities consequent upon time operate. Another person on which you depend may die or leave you to your own devices in another way, for instance.

The Elizabethan poet-dramatist, Ben Jonson, created in his miser, Volpone, in the play entitled Volpone, or The Fox, a man who thought he could use gold to buy what other people tried to be – poets, orators, moralists and blessed and holy spirits. The advantage of gold is that it buys everything, or so Volpone thinks, and there were good reasons in the world of Jonson, like a new class of merchant adventures and stock-holding rentiers of the sixteenth-century in England, to believe that may be the case then for more than those born to wealth and title. The key words in the early passage where Volpone greets his gold, calling it as precious to him as the sun is to the waking earth, is ‘price’ and ‘worth’ for they are indistinguishable to him.

Such are thy beauties and our loves! Dear saint, Riches, the dumb God, that giv'st all men tongues; That canst do nought, and yet mak'st men do all things; The price of souls; even hell, with thee to boot, Is made worth heaven. Thou art virtue, fame, Honour, and all things else. Who can get thee, He shall be noble, valiant, honest, wise,—

Christopher Marlowe’s sullied and antisemitic play The Jew of Malta has its Jewish hero, Barabbas, named after the thief preferred to Christ for pardon by Pontius Pilate from Roman law. Barrabas thinks of having and holding together forever ‘infinite riches in a little room’ . He thinks he can ENCLOSE all – the phrase is an early version of ‘having it all’ – by ensuring his wealth is both enclosed and compact in hard form and the sole arbiter of value, beyond that of a king’s power and appearance of achievement. What he must have is:

... costly stones of so great price,

As one of them, indifferently rated,

And of a carat of this quantity,

May serve, in peril of calamity,

To ransom great kings from captivity.

What he fails to see is that both these hings may enclose him captive too in a space of the same ‘little room’ it demands, as its security and thus shrink him too:

This is the ware wherein consists my wealth;

And thus methinks should men of judgment frame

Their means of traffic from the vulgar trade,

And, as their wealth increaseth, so inclose

Infinite riches in a little room.

Amazingly Marlowe’s wonderful line is used in all kinds of context. here in a n academic article on marketing eBooks for huger profits using less space. You can commoditise ‘it all.

Neither Volpone nor Barabbas succeeds in keeping either their wealth or what they think it buys, which was, they thought, ‘it all’. Both gave up any chance of being all they could be by thinking that merely satisfying the desire to ‘have it all’ by increments and ambitious plans focused on their ownership of the means of production of ‘goods’ even abstract goods like health, was sufficient exchange for being happy and good.

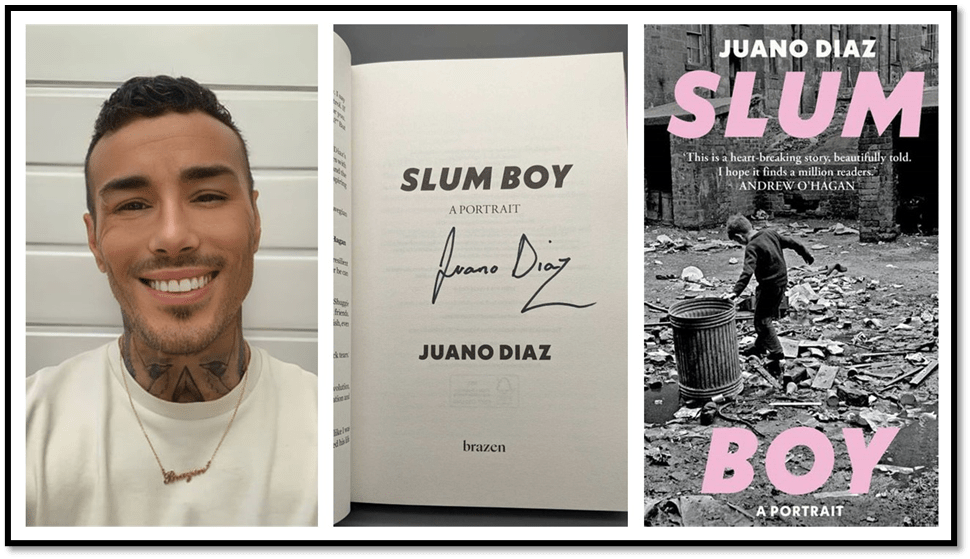

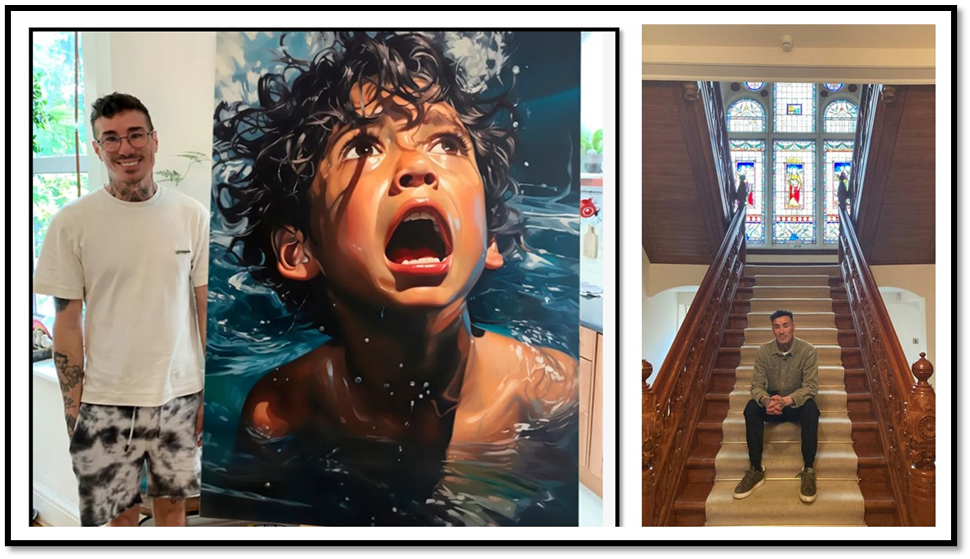

I am hoping soon to finish a blog on Juano Diaz’s wonderful 2024 memoir Slum Boy: A Portrait. Diaz looked at in the present could easily be mistaken for ‘having it all’. He has a highly cultivated good looks and a loving husband and they both have an adopted son. They all have a sumptuous mansion house in which to live. His art is highly regarded and he knew and knows celebrities other people dream of knowing from all realms of a wide range of art and culture. For these things I suspect from the information I add he feels lucky to BE in in this position rather than HAVE a lot of the good things in life, maybe ‘all’ of them. When he wrote his memoir and presented it to the novelist and journalist, Andrew O’Hagan, he wanted to name it Lucky Boy: A Portrait.

Here is how Pauline McLean of the BBC tells the story:

Andrew O’Hagan read an early draft and sent it off to a publisher. He originally intended to call it Lucky Boy but it’s been retitled Slum Boy.

“I was being ironic but I have had a really lucky life. It could have been so different if I hadn’t been adopted. I don’t even know if I would have been here.”

“When they suggested Slum Boy I said no, we can’t call it that. That’s completely derogatory and then I sat with it and realised it works.[1]

It has not passed me by how often the verb ‘have’ appears in Juano’s words but they are not words ever applied to what he has got or owns but what he had and how they made him what he is. After all, the ‘luck’ of his life, he sums up as being ‘adopted’. Anyone who reads the story of the process and outcome of that adoption will be circumspect about calling it ‘luck’, at least in all its moments – those where he is actively belittled by his adoptive mother, where having won through to seeing the love behind her sometimes meanness of spirits she dies, and where his adoptive Dad who blesses him with the most extended of Romany families, rejects him for having been found in bed with a young man, Mario, refuses to give that life up, even though Mario himself rejects him, fearful of being ‘outed’.

It is not having ‘it all’ (or at least having more than had of various good things) at any point of his life that defines Juano but ‘being it all’ within his life. We sometimes call that ‘owning’ your life but that is another misuse of a ‘having’ mode. It is knowing that by being yourself, you can be diverse things to diverse people, even those people of you are capable of being serially or simultaneously. I will write about this in may blog, because it is a lovely book. Juano does not have it all because he is Juano Diaz and has what the fortunate man has, though it’s worth an envious viewing in the collage below:

He has it all because he has been, through painful loss and sometimes painful gain, the son of many fathers and mothers: biological or chosen, secular or religious, one of which – the druggy ‘Daddy Ronnie’ waves goodbye to him until he loses ‘every trace of him’ as he swims int the Barrhead Dam lake, where unbeknownst to either, he will drown. This happens on the first two pages of the book. We owe it to more than the primacy effect of memory recall that not every trace of Daddy Ronnie is gone forever 9indeed as he dies young John learns how beautiful men can be in his eyes, but is redeemed, washed clean and blessed in what he contributes to the boy ‘lucky’ being as John Gormley, John Macdonald, ‘Pearl’, Juan the son of ‘French’ heritage (mistaken as Jean presumably), and, with others less ‘proper’names, the Juano Diaz, a surname of Spanish or Mexican South African immigrant birth lineage from Jagsy, his biological father, and the only one he learns to dislike for abandoning him and his mother before his birth. Being is a labour of love and its gains AND LOSSES, rom all of which you learn. How poor a thing is ‘HAVING’ then next to BEING, even if you need some luck along the way and the bits of yourself are difficult to assemble and often named by bad words. Strangely enough though Granny Gormley, she of the saying ‘the wee bastard’, is one of the first redeemed characters of this book where memory redeems everyone.

“My hair is jet black, not red like Mummy’s and not blond like Ronnie’s, and my skin is olive, not red like Mummy’s or white like Ronnie’s. My name is John, but Granny has always referred to me as ‘the wee bastard’.”

An maybe the beauty of the book is that everyone in it helps Juano to his beautifully destined being, or so we feel, as in this chance sight in the street where Juano is at his lowest. Seeing a homeless man drunk in the park, John notes that “his hair flap flops in the wind like a tattered flag… His arms are like brushes, creating a frenzied masterpiece in the air.” The artist is now in the making.

So be it all not have it all.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Pauline McLean (2024) ‘How the art world adopted Glasgow ‘Slum Boy’ Juano Diaz’ BBC News online [23 February 2024, Updated 24 February 2024] Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c4nxlv40lv5o

Nice

LikeLiked by 2 people