When do you feel most productive?

“…,the job of remembering is to reassemble, to literally re-member, put the relevant members back together, But, what I am getting at is the re-membering is essentially not only an act of retrieval, but a creative thing, it’s an act, an act . . . of the imagination”.[1] Reading the play and some other things before seeing Simon McBurney and Complicité’s revival of the play mnemonic by the National Theatre, which I will see, with Geoff, in the Olivier Theatre at 7.30 p.m. 10th July 2024.

Simon McBurney first spoke the words quoted in my title in the production of this play at the Lyttleton Theatre in 2002, twenty-two years ago. Now he returns as its Director and when I booked, it was as heavily booked up already as it had been the first time round when Théâtre du Complicité were considered so revolutionary a team in drama creation that they became a French not an English theatre company. At the time, ideas that British theatre was moribund were rife. They speak OUT FROM Jackie Fletcher’s account in The British Theatre Guide’s online reviews of Théâtre du Complicité , which at that time seemed always to be labelled in full Frank French not in the unaccented (English) ‘Complicite’ on the play text.

The original company was set up by a small group of practitioners who had trained in Paris with alumni such as Lecoq, Gaultier and Pagneux in a theatrical vein that prioritises the physical and the visual. They gave themselves a French name because they didn’t believe that they would get funding for their type of work in Britain. But they did, then at least. Those productions of the early and mid ’90s, such as Durrenmatt’s The Visit, Street of Crocodiles, Out of a House Walked a Man, and Lucie Chabrol defined the style visual, physical, ensemble pieces devised by the company. But the mainstay behind all of the considerable creative output, the visionary guiding the voyages of discovery to new theatrical worlds, the imagination that could stimulate the company in devising and to envision a performance in its entirety with the technology that makes the work of Complicité so outstanding in terms of traditional British theatre, that is Simon McBurney. And I’m going to make no bones about it: to my mind McBurney is a genius.[2]

Having read the text of that first production myself now, I think the idea it embodies is still as authentically novel as a piece of meta-drama as it was that not only examines what it is to assemble people, words, and lots of properties of the theatre into a kind of whole but also use it to reassemble fragments of history and historical reference so that they constitute a memory – a memory from various past times or even nearly present ones that will themselves constitute something memorable in the future.

Lyn Gardner reviewed the play for The Guardian when running then at the Riverside Studios, now lost to us, in 2003 and witnesses to it having precisely that effect, in words that we rarely see in the pinched type of reviews:

Let me put it very simply: I think about the world differently now than when I entered the theatre, and I know that I shall remember Mnemonic all my life.[3]

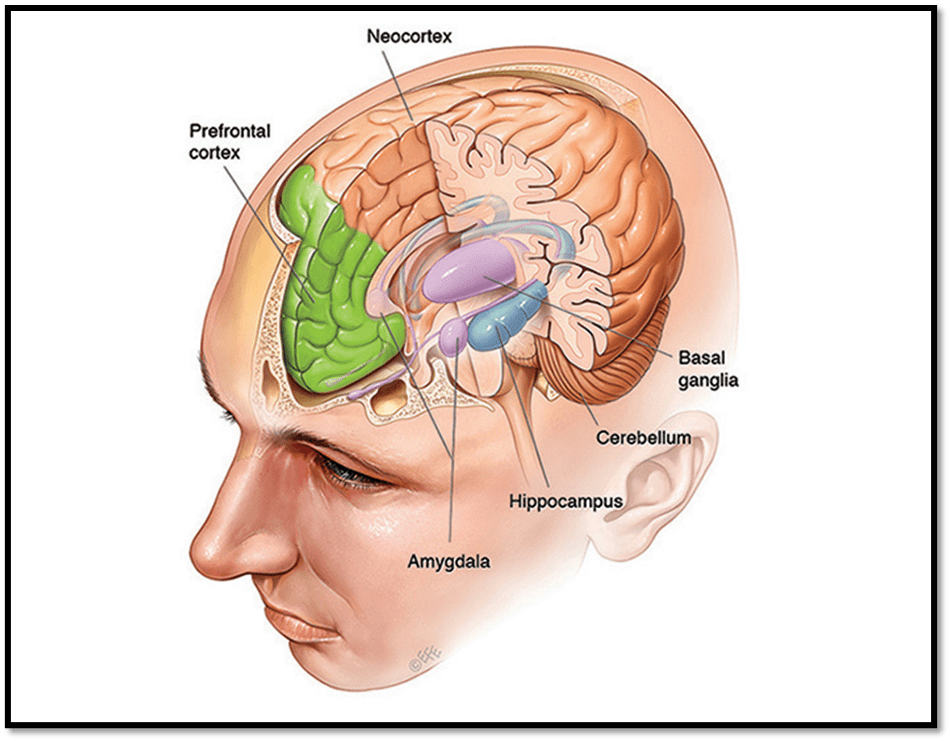

If everything is constantly changing, even the form of our memories and the psychosocial connections we build on these memories, it follows that we must always be remaking that which without us doing so would be forever unmade, or in the process of unmaking. The basic metaphor for this in the play is the understanding that memories are merely patterns of synaptic connections in the central nervous system, that can otherwise be described as a map, but not a ‘stable’ but a ‘chaotic map’: ‘ so the action of memory therefore is a kind of demented and unimaginably high-speed orienteering round the landscape of thew brain . . . so perhaps what happens as we get older is that we lose our compass’.[4]

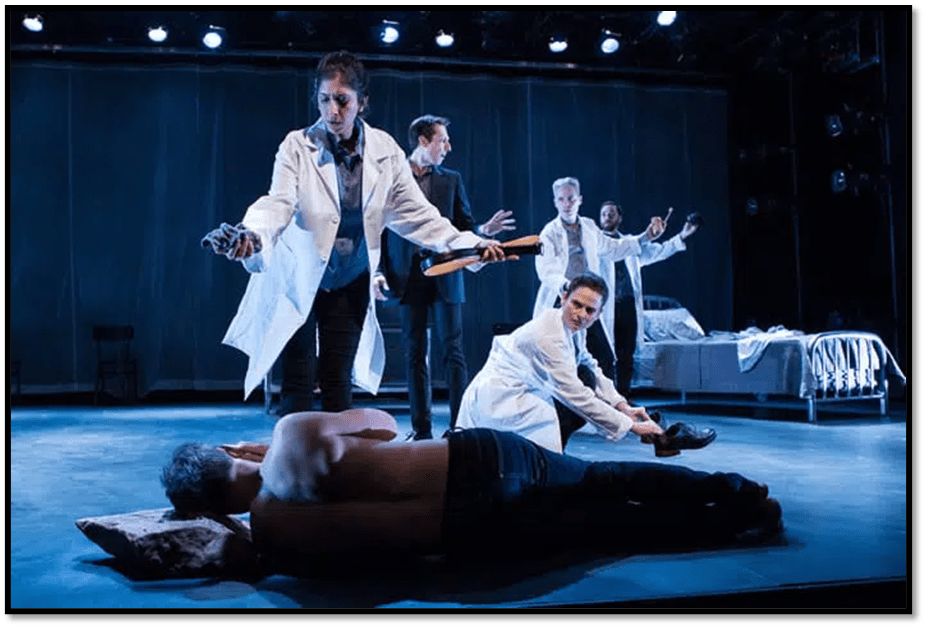

From the evidence of the text and photographs retrieved from past productions such orienteering, with and without a compass, is how the actors and props are made to use the stage space, visibly and audibly changing their identities , and even their forms. Thus Lyn Gardner again:

All this is done with the lightest of touches – the evening is very comic – and the most startling theatrical images. The production’s stark simplicity is enormously engaging: a chair becomes a body, trains thunder across Europe, a museum is conjured with a picture frame. There is an exquisite economy about the stagecraft, no excess.

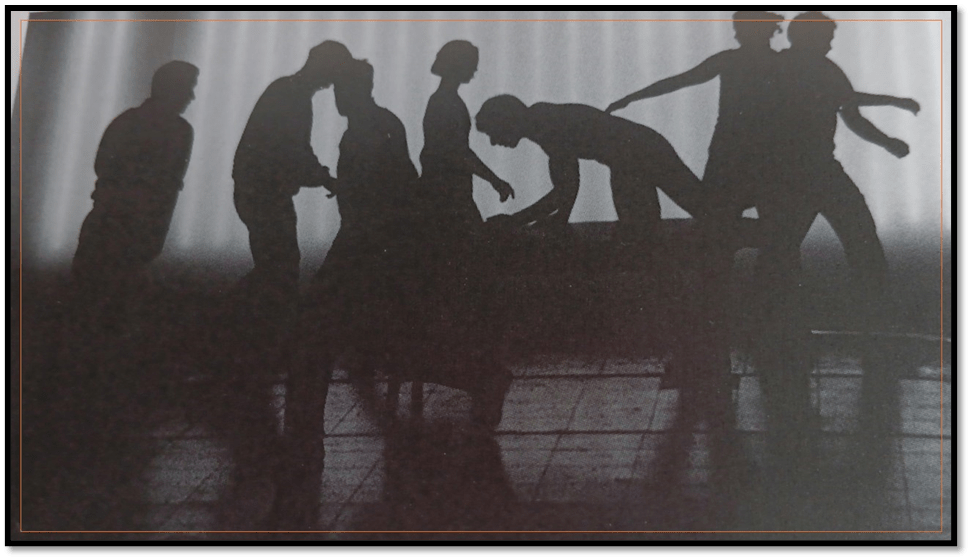

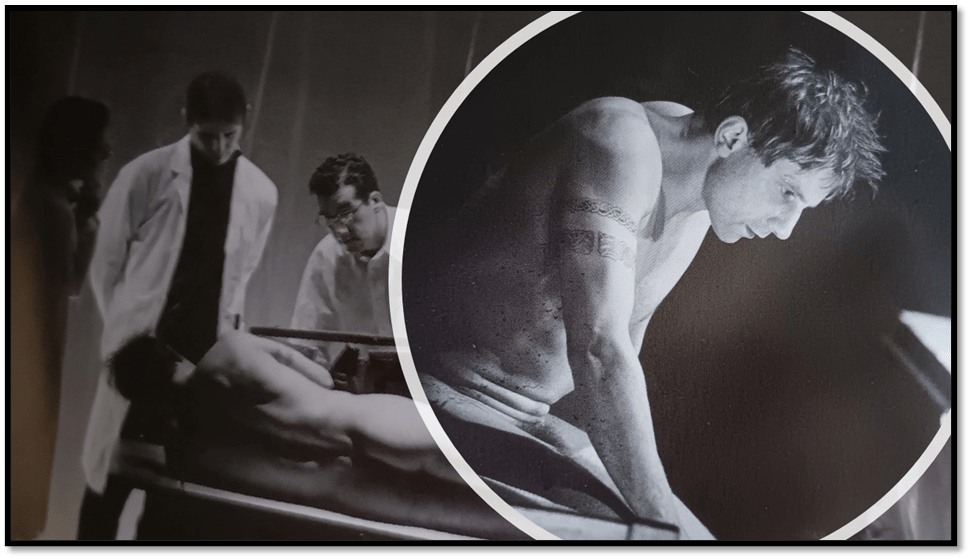

The stark black and white images of the original production, in photographs by Sebastian Hoppe convey the lightness of touch and some of the metamorphoses achieved by simple stagecraft (mime and motion, light, shadow and props forming shapes.

Otherwise apparently simple puppetry (by the standards of War Horse at the least) from unusual materials, such as a chair becoming a body, cabe used as in this still captured from a later production in the USA:

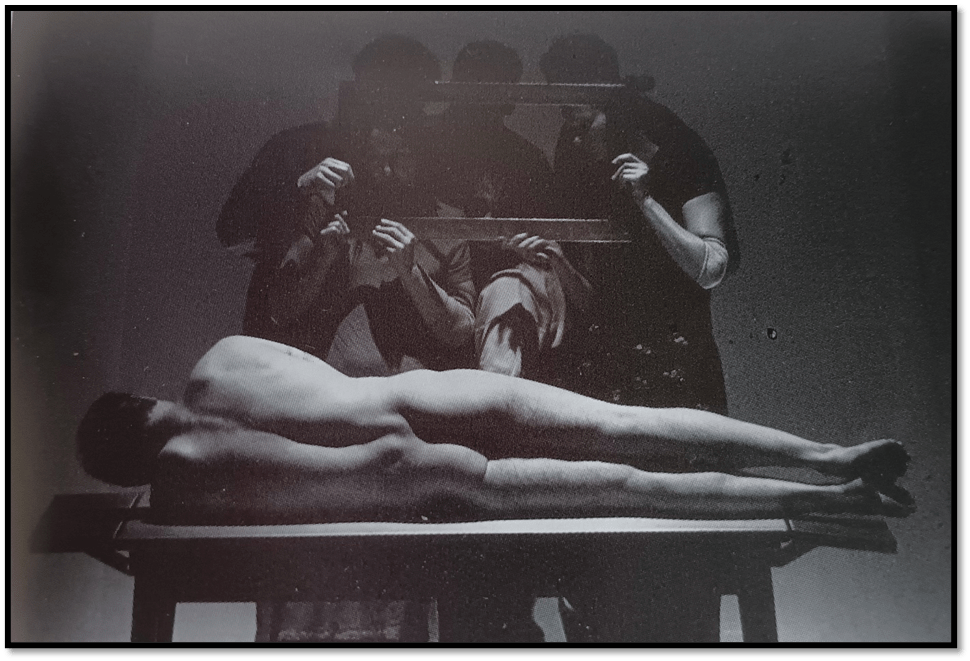

In the picture below crowds jostle to see, through a frame the body of the Iceman in a museum. Gardner tells of his place in the play thus:

Interwoven with these stories, and other smaller stories, is an account of the discovery of the Ice Man, a 5,500-year-old corpse found on a 3,000m alpine peak in 1991. Who was this man who froze to death alone on an icy mountain all those centuries ago? Why was he there? How many songs did he know? What is the thread of collective memory that links him to me?

In the photograph above the naked body enacting the stiffness of the Iceman is McBurney, but we know that, from the text, the critical accounts and the other photographs that he was also Virgil, the man whose wife has kleft him perhaps to seek her migrant Jewish ancestry. And we know others take on the Iceman role (things and persons).

Clearly the nudity is sustained in this role in the productions of the early noughties for Jackie Fletcher, seeing the same Riverside Studios production, says, with tongue in cheek:

As an end note, I must add that while McBurney is the only actor I’ve come across since the sixties willing to spend a quarter of the performance stark naked, with that beautiful, physically trained body, his bod doesn’t influence my judgement an iota! And if you are going ‘methinks the lady doth protest too much’ you are wrong. I’m only in love with his imagination.[5]

The production pulls considerable punch then in terms of the means it uses in an actor’s repertoire, although there is no guarantee that this production will go for the same approach with McBurney now as director rather than leading actor, and with a whole history of differing receptions of the play behind it. Moreover in 2001 it was in the Lyttleton. This time around it is in the Olivier, an enormous theatre space with enormous potential for mechanical and digital innovation. I suspect simplicity may be more notional than actual in this production. Some interim productions use large screens that aren’t mentioned in the text, but are obviously legitimate means of further fragmenting the style of enacted delivery of the scene’s messages. The fact that the Olivier is not a proscenium stage as such will necessarily be taken into account. The production is refusing to sell its ‘front stalls’ seats as yet and warns that once they do so, they will come with conditions to be understood by those purchasing the (how exciting). But see the large screens on this American proscenium production:

Moreover, this is a play about time – and it could not be otherwise if it is also a ‘play about memory’. If you juggle with the elements of experienced time, the play needs to anchor its own ‘present’ , which itself changes continuously, as the play ages in theatrical and art history.

And Jackie Fletcher was clearly thinking about more than Simon McBurney’s ‘bod’ when she watched the play because she enters into a debate – a contemporary one then – that the theatre was becoming depoliticised and uses this play as an instance that it is definitely not the case:

The narratives might be profound and engaging but it is McBurney’s style of theatre, the visual imagery, the sound and lighting effects, the use of video projection, and the beautiful physicality, that draws us in to a common humanity in a performance of stunning imaginative power. And I will go out on a limb here. While we are engaged in a discussion about the demise of politically engaged theatre in Britain, this work is political. There are no overt political references, but it is conjoining us to go on a quest of self-discovery; to see ourselves against the backdrop of the global powers shaping our lives. And, in its style, it is an encouragement to open ourselves up to the senses, to human compassion, understanding. And, as they used to say: ‘The personal is political’.

And I think she is right as far as my reading of the text is concerned. Even Fletcher though is inclined to represent the dictum from 1970s feminism in scare quotes: “The personal is political”. This raises another issue. Just as, if the play is to reference time and memory its stagecraft will have to be updated to our own contemporary, in some ways at least but , if it is political, certainly in its political reference. The text I read will have changed too in the production in all probability. If not, its references that were meant to be modern at the time will sound like ‘ancient’ history too.

The prologue establishes early that we moder ‘theories of memory revolve around fragmentation’ invoking the storage of elements of each memory in ‘different areas of the brain’.[6] Even the diagram below only largely looks at executive functions of that storage, ignoring widespread distributions in situated brain processes in visual, auditory and motor brain functions, for instance.

The idea of fragmentation, though a fragmentation actively being reassembling, deconstructed and reassembled again, will run through the play. I understand that the prologue is (or was) delivered like stand-up comedy – the whole evening felt like serio-comedy to both Gardner and Fletcher – but its aim seems to be to locate us in a mind-set open to the fragmented stories and means of telling them in embodied manner that is to come. We have to assemble our present the prologue insisted thus – the text written in 1999 asks its audience to think back a little, perhaps to: ‘New Year’s Day 1999’.[7] As it asks about each audience member’s contingent facts of weather and health at the time (if a hangover is a health condition), it widens the ‘fragments’ allowed in to comprehend spatial-temporal events globally – including political events:

So now we will go further back. To autumn 1991. September. Where are you? Can you remember? It’s just after the Gulf War and before Yugoslavia starts to split again. Perhaps it’s completely empty in your imagination. … Or perhaps there are one or two fragments . . .[8]

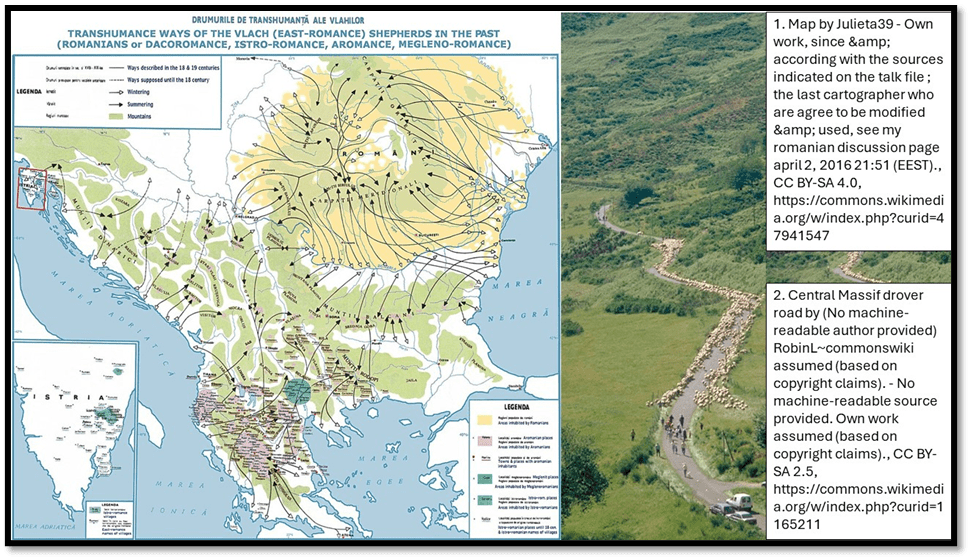

For most in 2024, it is not just because these events are a much longer time ago but that they will have lost significance to a world whose conflicts present differently. This will be even more pressing in a play that deals with, amongst so much else, Jewish diaspora and the cause of human migration in other contexts, but, even in the case of the Iceman 5,500 years ago, the possibility of the flight from social violence. Will the reference be to Gaza and to mass migrations that have lead us to the sad, meagre and self-centred national politics of ‘Stop the Boats’ as a political slogan. How this production deals with migration and issues of what the play calls in one of its spoofs on migratory politics, by a theorist of the animal nomadic impulse, ‘transhumance’. Transhumance is theorised by the comic English Delegate to the Iceman academic conference, who is frankly presented as an up-himself twerp or geek.

The conference at Bolsano in an American production

Starting a speech covering a third of the page, he starts: ‘ Now I’ve only word to say on the subject and that is transhumance. Now transhumance is, as we know, seasonal. So ….’ and on he drones on whether the animals migrated are cows or sheep. He concludes on sheep, ending vapidly thus: ‘They are remarkably loving creatures which brings me to my point, basically I’m saying that he’s a shepherd, thank you’.[9]

So much for the English and their ‘one word on the subject’. The translation machine at the conference is broken so we only hear the Greek , German and French delegates in their own language. This is a conference at Balsano that sounds like one from the Tower of Babel, where everyone is speaking in tongues. What is clear is that English speaking delegates defy openly any reliance on the Iceman seeking asylum from violence. How will this play in the context of monstrous racism like that of Suella Braverman now the official discourse of the governing political Party, if not (in public) the government itself.

Let’s go back to Jackie Fletcher however for her reassuring words that suggest to me that however updated this play into a more savage, feral and visceral set of discourses lying behind Gaza, Ukraine and the European response to migration and a world destroyed ecologically and politically by its heritage now holding up barriers to the migration of its long-term victims. She says the lead actor’s ‘solo prologue to the twin narratives that are interlaced in Mnemonic’ is:

… utterly compelling in its fun and its profundity, presented as it is by a character so touchingly human, manic with ideas that range from the philosophical to the absurdly mundane. It is an engagingly anarchic rant by a man desperate to communicate his feelings; a man rendered vulnerable because he is unreservedly open to feelings, cultural ponderings and, above all personal memory. A man who cares, and is trying to make sense of experience in a world of forgetting; a world that deprecates the sensual experience in favour of materialism, grabbing the latest gizmo. And how can we be rational beings if we ignore the senses? It is the senses that give our brain the information we need to negotiate survival. This is a man who has no defences except his mind and that mind has lead him into a labyrinth of potential meanings. He makes us laugh, he is endearing, so we are opened up, made ready for further experiences.

What this play confronts according to her is the Everyman of modernity – a neolithic survival played by an role in the play, Virgil, played by the same actor as the prologue-speaker. It is like a version of King Lear meeting ‘unaccommodated man’ (naked and cold in a storm of rhetoric around him) but played for laughs in innovative theatre.

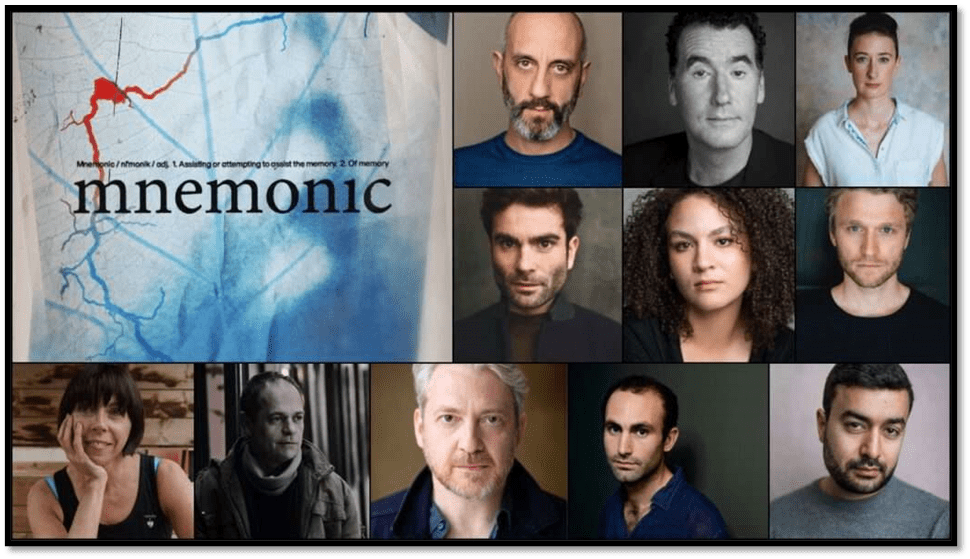

Some role. McBurney seems to have cast Richard Katz (the first mug shot on the top row below) in the role he once played. So demanding:

Katz is eminently capable. We know from his past credits of waking up in the role of Virgil / Iceman and the bearer of sad meanings about political and other memories behind the fragmentation of human being into its present ontology, but it’s still a chilling task.

Any one role’s success depends on a good company and Simon McBurney must know this better than anyone. And this is going to be a great company. I have read the play but I cannot predict the changes inevitable in its text and means of performance, Here are some bits I am yearning to see performed in the way the team chooses:

In the American production the Iceman wears boxers and I wonder how this will be handled and what it tells us about the handling of nudity in the modern theatre, supposedly much more ‘liberated’ than the 1990s in this year’s production. In the still collage below we see the iceman being dug out of the ice (‘Naked except for a strange grass-filled shoe’) and then forensically examined, having been ‘dehumanized by becoming public property, a national monument’ in Scene Fifteen. Journalists wonder why it is ‘naked’ and one whether it ‘has a dick’. Being a ‘national treasure’ two nations haggle over whose nation it belongs to – rarely done favourably with migrants but they be over 5000 years of age. Borders become important, even the ones defended bu boxer shorts.

In the play text, nudity is a symbol or emblem of human vulnerability – of subjection to inhuman objectified gaze but also of human fear of failure in challenges – in a piece that tells a parallel story to that of the Iceman, of a man named as Carlo Capsoni (real or imagined but bornin 1903 and disappeared in 1941 according to the play), who plays the pianoforte like he climbs mountains and whose body is eternally confused with the Iceman in the play. His body is symbolically stripped in metaphor. This is him speaking to his piano student:

When we play a pierce of music for another person we often feel frightened, sick with fear, like a mountaineer with vertigo.

His tone softens.

Why? Because we feel naked. And what does naked ness remind us of? It reminds us that our fears are natural, that we are all vulnerable. So, let us agree that we are both frightened, stark naked and that we climb this mountain together.[10]

So much then for boxer shorts as a means of enacting this. Yes. There is a problem, but why go to the theatre if so easily shocked, as if all art should be reduced to the level of mid-nineteenth century bourgeois narrowness.

One scene seems to have played very similarly in both productions that major in the photographs I’ve found. The scene where viewer’s frame, using a frame used for a work of art, the naked body in order to objectify it (they wear rubber gloves – realistic when they are the forensic team, symbolic of art audiences. Here in 2001:

In the American production the boxers sort of lose the whole point of being vulnerable to the gaze in a real sense that art, as Capsoni, says, has to defy:

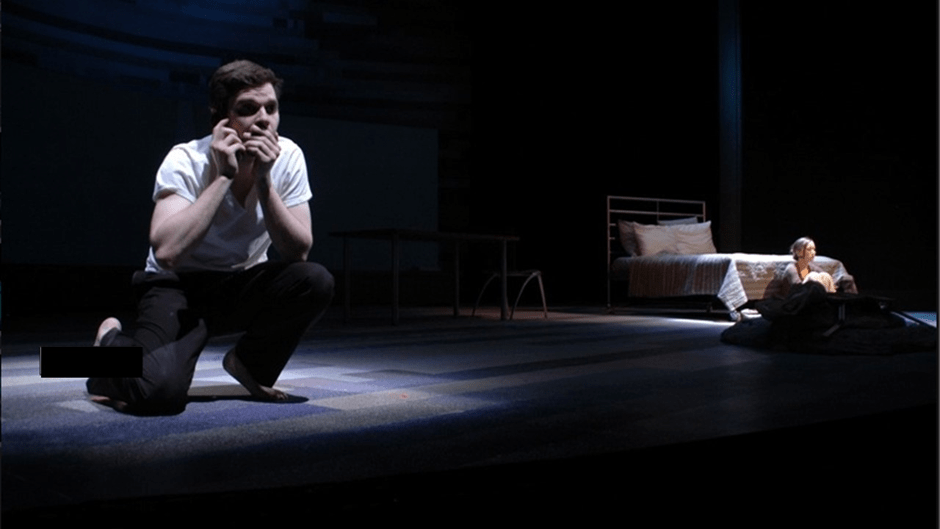

Dealing, as it does with people who travel through boundaries and borders, the play must too deal with the means used across those boundaries – language and its many kinds, not comprehensible to all equally, being one. But the stage space must deal with how this is conveyed and distances must be created between actors of all kinds and enacted, using properties, genuine spatial distance or perspectival tricks. See these examples. I am just intrigued about this in the Olivier space (and excited):

In the scene above choice of place on a seat and the gesture/ body attitude of sitting increase distance as well as gaze. Fragmentation is covered by use of screens. Below more conventional stagecraft tricks make the mobile phone emblematic in a conversation between parted lovers.

The character Spindler below intrigues, standing before a German newspaper report of the discovery of the ice-encased body. But let’s end with puppetry as in the second still on that collage. Puppetry has become more common in the theatre and used to brilliant effect. Which way will this production turn. Retain the simplicity of how forms can be changed in stagecraft (a chair into a body) or use more sophisticated methodologies. That might matter if modern audiences are to be convinced that this is about ‘memory’, as they have learned to know it.

Here then, I will end, looking forward to seeing this production in July (so long away). I will revisit and link the blog then to this one and vice-versa. You need to rush to get your own tickets.

Love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] From the speech of the main actor, named as ‘Simon’ in this text for Simon McBurney in the 2001 production, in Complicité (2001: 4) mnemonic London, Methuen Publishing Limited. NOTE: MY OMISSIONS IN QUOTATIONS INDICATED BY …., The text’s own use of missions is represented differently (as . . .).

[2] Jackie Fletcher (2002) ‘Review: Mnemonic’ in British Theatre Guide (online) Théâtre du Complicité, Riverside Studios. Available at: https://www.britishtheatreguide.info/reviews/mnemonic-rev

[3] Lyn Gardner (2003) ‘Review: Mnemonic at Riverside Studios, London’ In The Guardian (Wed 8 Jan 2003 02.28 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2003/jan/08/theatre.artsfeatures2

[4] Complicité op.cit: 4

[5] Jackie Fletcher op.cit.

[6] Complicité op.cit: 3

[7] Ibid: 6

[8] Ibid: 7

[9] Ibid: 68 – 69.

[10] Ibid: 19

3 thoughts on “I feel most ‘productive’ when I think about engaging with art that matters, and will survive me. A blog on preparing to see ‘mnemonic’ at The National Theatre in July.”