What are you most excited about for the future?

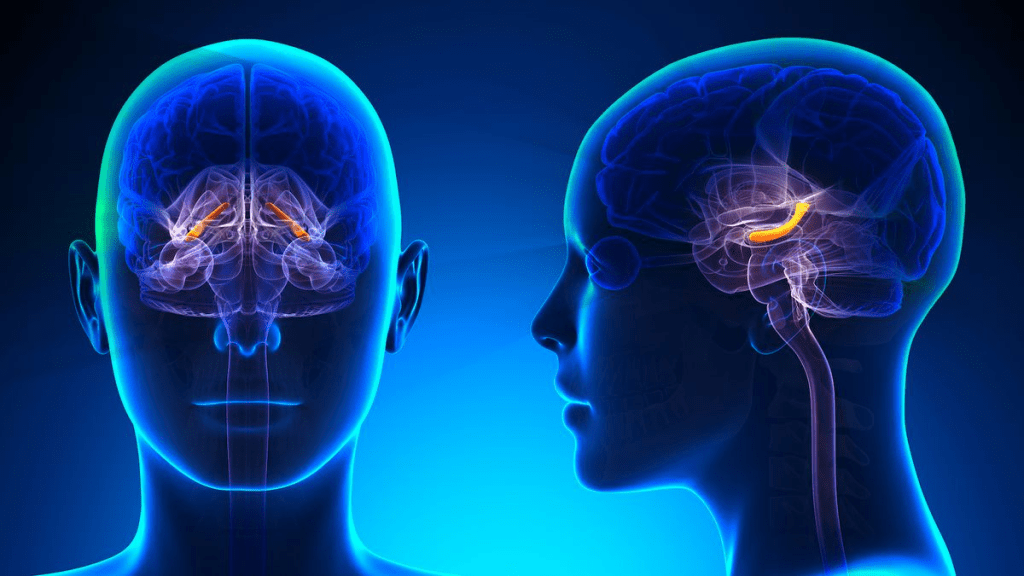

Last night I saw the play Mnemonic at the National Theatre. I was intending to blog on it, but today is too full to allow it – with exhibitions on Michelangelo and the Expressionists to see with a dear friend, Catherine. This blog will be somewhat of a filler but stems too from themes in that play. The play used expert collaborators in its making and in a companion book to the production, Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site], a neuroscientist who acted as expert in neuroscience, Dr. Daohna Shohamy, raises issues that show that in the brain, memory functions and those of imagining our futures are close related neurologically, in, for instance the role of the seahorse-shaped (a fact that gives its its name) brain component, the hippocampus. So let’s ponder the hippocampus, the wondrous seahorse.

One of the most remarkable recent discoveries in memory research is that memory’s primary role may be to guide us into the future, not merely a record of the past. Patients with hippocapampal damage struggle not just with new memories but also with imaging the future. When asked to envision future events – such as plans for the next weekend, or their next birthday party – their minds draw a blank. Bran scans of healthy individuals show that retrieving past memories and imagining future ones both engage the hippocampus. Neuronal activity in the hippocampus reflects upcoming possibilities – future, not just past or present. (1)

A fuller summary of the the play’s themes would insist [as I did in a preparatory blog on this show a little time ago – see it as this link if you wish] that what the hippocampus does is to assem le and reassemble data of all kinds to construct the thing we call a ‘memory’ or a picture of our future- our imagined prospects including data about how we might feel about each: sad, hopeless, excited …

So what am I saying when I answer a prompt about ‘what excites me about my future’? I am, in fact, constructing a whole assembly of data that includes information about imagined pictures, words, dramatic interactions, AND feelings that cohere and make a kind of sense. These constructions have then little immediate relation to an accurate description of the world as it was, is or will be. They are a combination of fictions that may not make us feel excited but could well have been so constructed such that they were fitted into the feeling we want to have about our future self and it’s adventures.

I suspect that I am not then excited a oug the future but, if I am lucky to feel such a thing, I am constructing a future that might represent excitement to me and hastening to build alliances good, or bad, relationships with others to achieve that future. The good alliances are those of cooperation, trust, and inclusive collaboration, the bad ones those of competitive relationships, equivalent to the later emergence of distrust, cheating, and backstabbing.

In truth, the future is never in our hands but is subject to how we shape it with or against others. It depends on what we think excites us. That little seahorses, the hippocampus, is a tool to those ends. Of course, hippocampal functions can be damaged by trauma of different kinds that creates massive diversity, even if there were not already neurodiversity possible in all functions. True alliance is an equality with diversity, where some some support and others get supported in each of numerous functions. We might give more than we receive or receive more than we give, but we will all still give and receive at some level.

All that, too, is being constructed and not just in and by individuals, for what we construct alone already requires constructions that cooperate or otherwise with us. To do this together requires extraordinary sharing at the level of our mental operations as well as bodies, exceptional ability to communicate thoughts, feelings, and sensations. That is the dream. That is the excitement of new ways of being.

All my love

Steven xxxx

__________________________________________________

(1) Dr Daohna Shohamy (2024: 138) ‘Neuroscience reflections’ in Tim Bell and Simon McBurney (curators) & Russell Warren-Fisher (book design) [2024: 7] Complicité: Mnemonic [A Site], Colophon, 131 – 135.