Nicholas Thomas performs on the stage, at Hexham Queen’s Hall Book Festival, the brilliant balancing act on Gauguin’s life and art written in his book.

This blog is an update and follow-up of a preparation blog on Nicholas Thomas’ book available at this link. Its title: ‘This is a blog on Nicholas Thomas (2024) ‘Gauguin and Polynesia’, in preparation of seeing him at Hexham Book Festival, Queens Hall on Sunday 5th May 2024, 11 a.m. Brilliant on anthropology of transsexuality’.

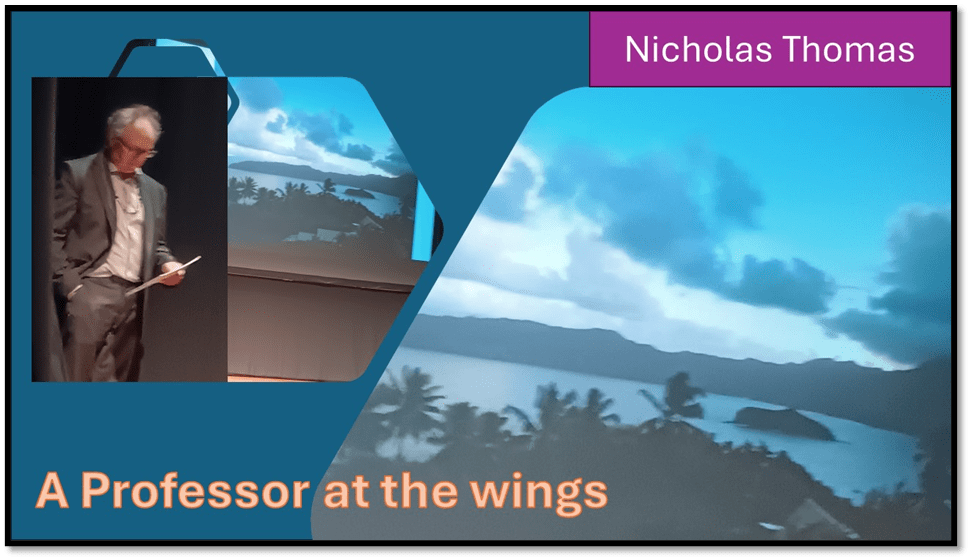

Since I see many live theatre performances I ought to start by defending the use of a ‘talk’ as a ‘live performance’. Nicholas Thomas is a Professor of Historical Anthropology at the University of Cambridge and associated with the curation of work at the Fitzwilliam Museum but, despite the almost typical professorial demeanour and look, noticeable as he waited in the visible bit of the wings of the Queen Hall stage to be introduced first and glancing over his lecture notes, this was brilliant performance indeed that diverted often and fascinatingly from both the text and examples of his brilliant book. He entered to a stage radiated by a slide, of his own photography, of a bay in Polynesia, Hexham has never looked like this on a promising-to-be-wet Sunday.

Good presentation of ideas and feelings about art needs performance – not as a charismatic add-on but as part of its message, and Thomas provides this in bucketfuls. I was pleased enough as I sat ‘anticipating the event’ to glory in the memory of the book – on my knee ready to be signed after the talk – and my pleasure that there would be visual illustration and visual examples used. But spare a thought too to the brilliant lighting of the event stage with its colour blemd achievements.

And so then on to the introduction. Despite the presence at on the stage of water refreshment and a chair, it was the lectern Thomas used, but used with the performance skills that only openly committed and engaged academics achieve. I don’t intend to add much to what I said about the content of the arguments of the book but to admire the skill of turning a lecture into public performance, addressing its themes.

For Thomas Polynesia is not a place interesting for its past but also its present and future, as his many illustrations show – particularly of the Sunday bonnets in the Protestant church of the modern Polynesian women whom, with obvious permission and pride, he used to illustrate the way in which Western fashion is owned and transformed in social performance. In the book, he uses cis and trans women to illustrate this and discourse about the representation of women by Gauguin. It is a presentation they admire.

Nicholas Thomas (2024) ‘Gauguin and Polynesia’, photograph p. 385

I was able to ask. in the Q & A session, Thomas about his representation of trans issues, which he touched upon in relation to the works of Yuki Kihara such as Paradise Camp, which opened up further ways in which Gauguin’s self-representation is rendered mysterious in his visual and written art, particularly the debate about the potential to homoerotic content in Noa Noa, of which I was not aware. It is mysterious because Gauguin never, as Thomas says, presented himself in private or public as other than heterosexual, yet as an artist had to queer that palette too.

However, Thomas began his presentation by addressing the elephant in the room – the difficulty that can not but express itself when Gauguin is mentioned in literary discourse despite the view taken of his art. Thomas instanced that with the slide of a review of his book in The Guardian, a favourable one he said, that nevertheless lead with the headline: ‘YOU CANNOT ENJOY GAUGUIN’S ART WITHOUT GUILT’. He could, had he wished, used the BBC documentary on the artist that polarised Gauguin between visual genius in his art and a man of dangerous politics and sexual preference.

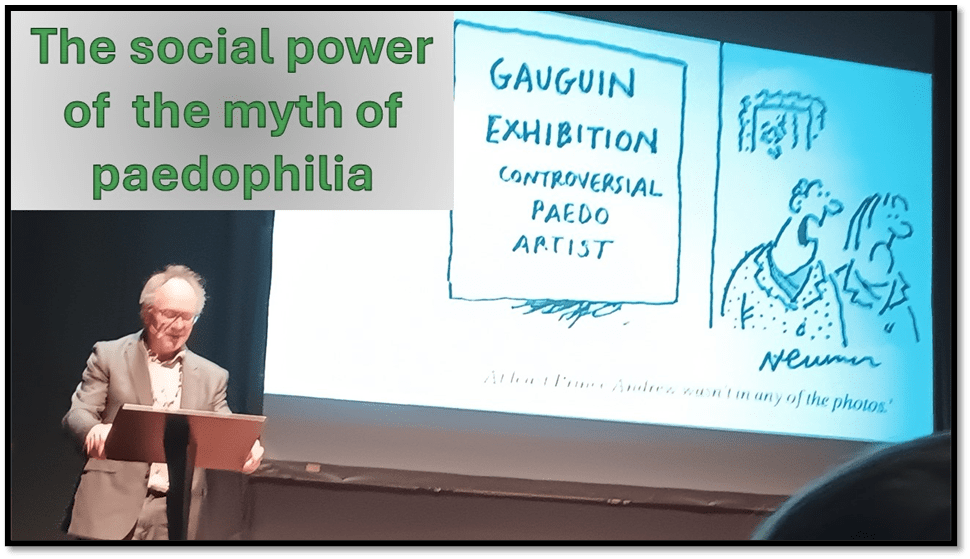

But he never laboured that point, as using the BBC documentary would necessarily have done. Instead, he stated the social power of the myth of Gauguin’s paedophilia with a cartoon. I say myth without contradicting the fact, as I think true of Thomas too, that there is a problem to address about the inequalities of power Gauguin exploited in many relationships – not all sexual – in his life. The myth is built around the central and monolithic representation of Gauguin as oppressor and the status given to the objects of his passions (which consistently makes them remain objects, not subjects) as ‘victims’. Instead he used, to raise the laugh for which it was intended, a cartoon (from The Daily Telegraph) showing Mr & Mrs Normal Average-Telegraph-Reader leaving a ‘GAUGUIN EXHIBITION’ subtitled ‘Controversial Paedo Artist’ with the caption of Norman Normal’s words: “At least Prince Andrew wasn’t in any of the photos”.

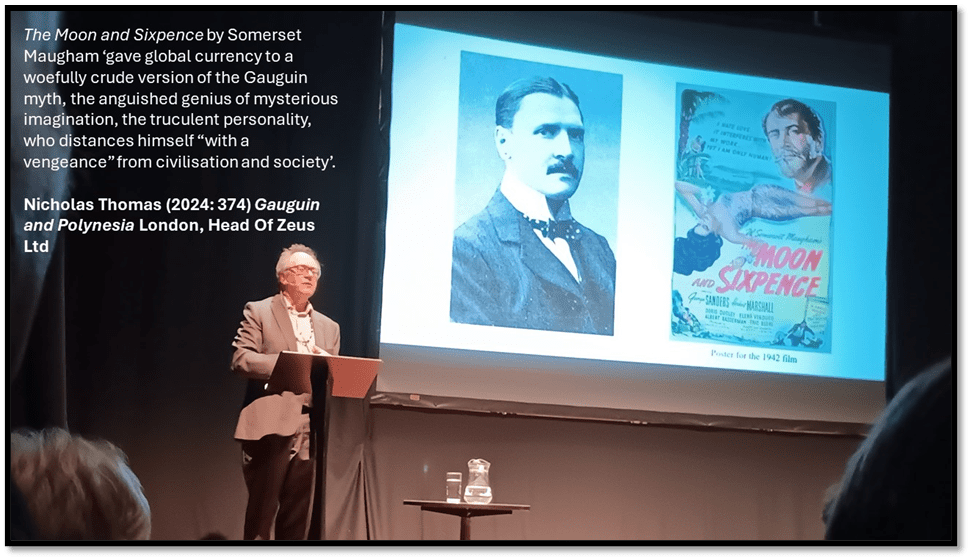

This is not, I hasten to add, illustrated thus in the book, though Thomas spent some time blaming Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence, as book and film, for spreading that version of Gauguin’s ‘dangerous’ sexuality in both book and presentation. There is, of course, probably much to say about the genesis of such thought in Maugham that, Tan Twan Eng’s recent historical novel The House of Doors (see my blog at this link) about Maugham’s own relationship to South-East Asian cultures might suggest was reflected through his experience of, his own American lover, George Haxton’s relationships with young boys in colonial relationship to him.

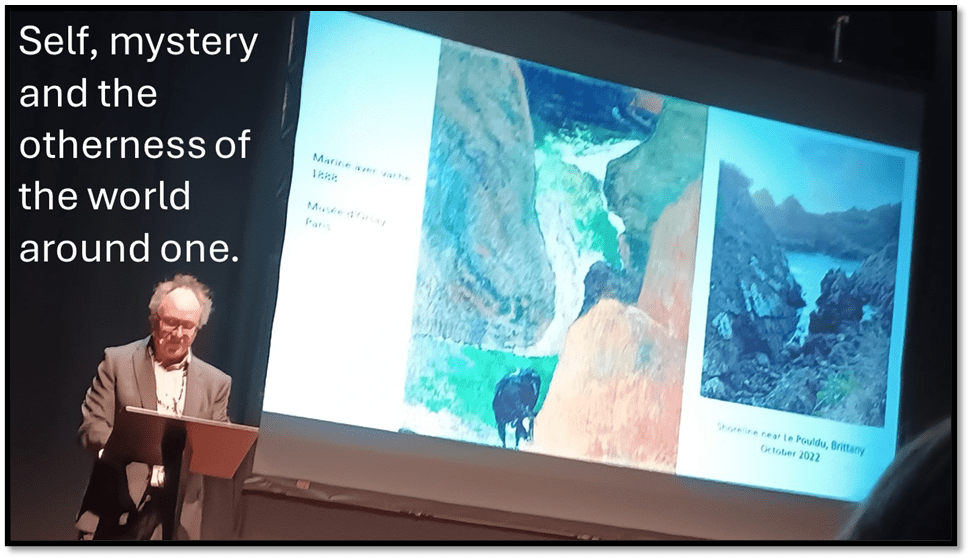

But much more was said in the talk, with new illustration thereof, of how Gauguin mediated as mysterious, in the sense of puzzling or ‘queer’, in the old (and perhaps new) sense of that last word, the relationship of self and the world. A painting not used in the book of a bay at Le Poldu, Brittany, illustrated the blend of realistic representation of the actual and the need expressed in Gauguin’s phrase ‘soyez mysterieux’. He could have added too how, by using the impossible high view-point and the threat of enclosure by the marvellous, the bold expressionistic (or Nabi – see my blog at this link) colour impositions and a cow as teetered on the edge of disaster as that in The Vision at the Sermon (1888) he threatened enclosure of his viewer in the dangerous depths under the painting’s surface.

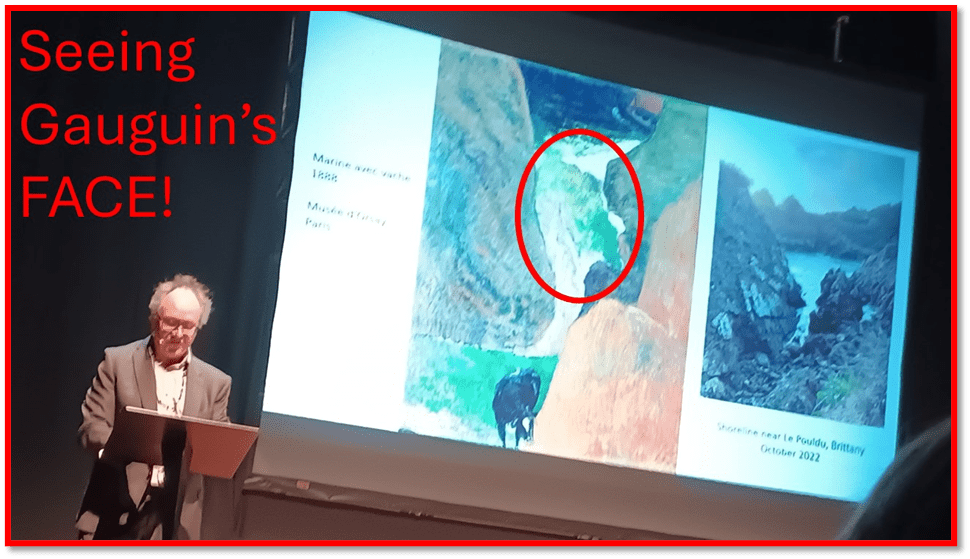

But what he did, for all the above is implied (at least if you had read the book or were avidly excitedly reading the painting at the same time), is deepen one of the throw-away remarks in the book that didn’t get illustrated there. Speaking of the painting, Red Hat, Thomas said there that its suggestion of a ‘head in profile’ in its hat brim. He continued by saying, almost as a throw away that: “Gauguin occasionally hid heads or faces in paintings …” (Nicholas Thomas (2024: 110) ‘Gauguin and Polynesia’). I had wanted an illustration there, but here one was and bolder and mird suggestive than ever. We see, he pointed out, Gaugin’s face profile in the deep enclosure of the water at Le Poldu.

One could say much more in praise of a professorial performance that highlighted an exciting and humane grasp of the ethics of human social life, like the book, and built upon it. This was performance in art history as art history needs to be if its is to rescue itself from the Andrew-Dixon-type elitist moribund it too often is.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

One thought on “Nicholas Thomas performs on the stage, at Hexham Queen’s Hall Book Festival, the brilliant balancing act on Gauguin’s life and art written in his book.”