What are the limits of responsibility to mitigate a massive continuing death toll in Gaza? Where, if anywhere, does my responsibility lie for the actions of people with whom I share a characteristic linked to my identity or is it, as of course it is, everyone’s responsibility (though more so of those with power of influence)? Calling out and preventing genocide extra-judicially. I reflect on an essay by Pankaj Mishra.

Gaza, without its peoples benefitting one iota from the fact, is at the heart of ethical debate in international politics currently. Evoking the issues involved in the invasion of Ukraine by Russia is a rather different matter, although some issues are the same, for there is no state of Palestine with a defensive military infrastructure defined in international or national laws, and no parity of offence and defence between Gazans and Palestine,. The latter is a fact despite the fact that a complicated and internally divided group with an active terrorist wing has become its elected regional government, of a kind. I say ‘of a kind’ because, not being a state or internationally recognised region ‘Palestine’ has no official means of raising an army, navy or air-force for its defence and remains a contested area in Israel owned by the latter. Hamas is, as it were and without offering this circumstance as an excuse for the strategy followed, as a result locked into the means used by highly secretive and unchecked unofficial militias , whose actions cannot be controlled by, and are therefore not the responsibility of the civilian population of Gaza not influential in Hamas. However, according to the Israeli Defence Force (IDF), Hamas is embedded in the population, using it as a ‘shield’ they say, though it must be an incredibly flimsy and powerless shield given the vast number of deaths of innocent children required to embody its shattered present state. Hence Palestinians die because ‘collateral damage’ is what happens in wars, says Netanyahu, and that definition of ‘collateral damage’ extends to the events that led to the death, by forensic strikes on well-marked aid vehicles three times, of foreign aid workers. It was a mistake, we are told. But that doesn’t account for the fact that the strike has met the need of an invading army to limit the availability of emergency food to populations and to use a supposedly illegal policy of starvation as a means of warfare. Today ‘new’ humanitarian ‘corridors’ are opened – but only etiolated versions of such corridors asked for before the bombing of AID vehicles and with about the same promise of security. This is a ‘solution’ acceptable only as a cover of continuing support for a war of attrition against a whole population.

What kind of sense of responsibility fired those aid workers? I am in awe of them, each understanding the potential costs to themselves and their now bereaved families but accepting the responsibility anyway to others. It is beyond my understanding. I have never lived with such responsibility. And, this is a question of ever-expanding significance internationally as even major military allies of the state of Israel have to face the fact that their citizens have become the victims of arms they may have supplied to the IDF. Outside of the Middle East, In the UK for instance, people speak of increased antisemitism. This was the case too during the last incursion (of 50 days) into Gaza by Israel. And although there is clearly NO responsibility for the war in Israel of Jews living in the diaspora, it is as clear that UK Jews feel they are being blamed and attribute this to unacknowledged antisemitism and nothing much to do with Israel per se. I am rapidly moving to the position that, if the cost of not being labelled anti-Semitic is support for the most oppressive of military actions in the Middle East that is craven to fear labelling whilst accepting others die to protect one’s reputation amongst liars of convenience, including a Labour shadow cabinet we need in the UK to replace feral Tory rule.

The relationship of an evaluation of the current state of what was labelled anti-Semitism and the world role of the Israeli state was a debate David Baddiel, to his credit, allowed to happen in his documentary Jews Don’t Count with the actress Miriam Margolyes (in November 2022, well before the current ‘war’ – the link is to the article on it in the Metro newspaper.

The difference of opinion in the programme, or part of it was summarised by Ruth Lawes thus in the Metro:

But David said he felt ‘no connection’ with Israel, adding that when followers write: ‘What about Palestine?’ after he tweets about antisemitism it is prejudice because ‘we have no collective responsibility as Jews for Israel.’

Miriam had a different take, adding: ‘I don’t agree with that because if you know bad things are being done by people to whom you are connected, strongly connected with, it is your duty to speak about it, to draw attention to it and try to change it.’ ….

David asked: ‘In what way am I connected really to Israel? A country that feels foreign to me. I’m an atheist. I’m a European jew. I basically just think Israel smishIrael. I’m not that bothered with Israel. It seems to me racist that as Jew I have to be more bothered about it because that’s not a stricture imposed on any other minority.’

Miriam responded: ‘I think it’s wilful of you to deny connection because they are your people. They are my people.’[1]

There is an intense debate here about the responsibility towards one’s people, wherein Margolyes says that the actions of Israel as a political and military state is part of the burden of identity all people who identify as Jewish must take on and which Baddiel thinks he can cast off any responsibility put upon him. That latter pressure he says is the opinion of racists (anti-Semites) precisely because he personally ’basically’ just thinks ‘Israel smishIrael. I’m not that bothered with Israel’. I find the attitude about the accusations of anti-Arab-racism against Israel hard to understand here however (even though I am not Arab), precisely in the same way I used to find apathy towards injustice occurring in South Africa under Apartheid hard to understand, though I am not of Black or white South African descent. I am not a Jew but I feel the Holocaust I believe not equally but with similar intensity to those other examples, and see the return of its mechanism likely to provide a ‘final solution’ to other things and people considered a problem by even established political parties.

However, I also think that David Baddiel has no greater responsibility to show support to Gazan Palestinians when they are suffering injustice than do I. In that, Margolyes seems unfair. But I think we have to look back at the context of Baddiel’s book and documentary, which has without doubt been used to diversify the comedian’s career and public reputation and to ensure a Zionist policy to be re-established in the Labour opposition. It was based on solid opposition to the support of Palestine in the Labour Party, particularly under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. That is the context Margolyes was responding to. It is analogous to her saying, so many times, that Corbyn neither had been nor was now anti-Semitic, though he undeniably made mistakes of judgement, especially around his unawareness of common anti-Semitic tropes when used in street ‘art’.

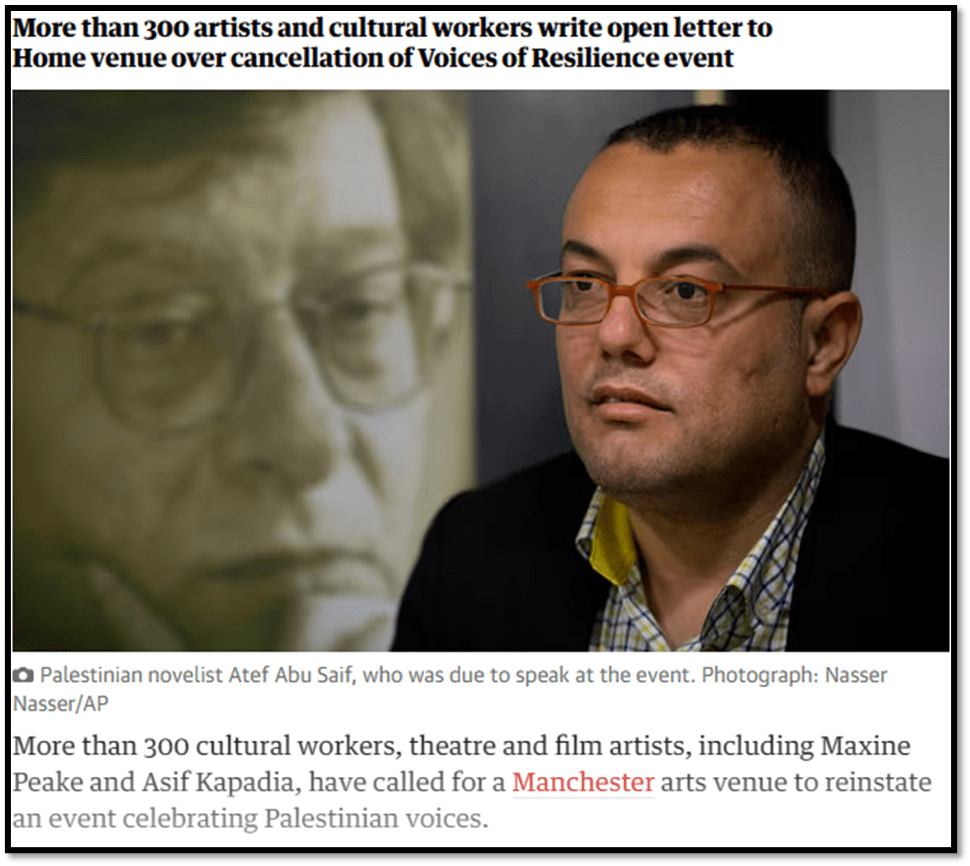

And part of that context was a widespread propaganda campaign by David Baddiel and Rachel Riley, amongst others, not only to convince other Jews that the Corbyn party was dangerously antisemitic but that other left-leaning non-Zionist Jews, such as the membership of the group JUDAH, Michael Rosen and, of course, Margolyes herself, were anti-Semitic. This has troubled me more as memories come back as supporters and even mere voices articulating a view that derives from Palestine have been silenced. Not long ago I wrote a blog on Atef Abu Saif’s eyewitness account of the first 85 days of the Gazan war (see the blog at this link).

Haroon Siddique (2024) in ‘The Guardian’ online (Tues 2 April 2024 13.04 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/apr/02/manchester-voices-of-resilience-palestinian-voices-cancellation-open-letter-artists

Since then an event in which Abu Saif was to appear at HOME Arts Centre in Manchester has been cancelled on the request of the Jewish Representative Council of Greater Manchester (JRCGM) because Abu Saif had compared the numbers killed in Gaza to those killed in the Holocaust / Shoah (I will use the Jewish term Shoah mostly hereafter in line with the political historian cited later, Pankaj Mishra) and found the former greater. This was described as an example of ‘Holocaust-denial’ by the JCRGM. Artists have rallied to protest the cancellation of Palestinian voices. The protest continues as I write:

In these contexts, it is difficult for anyone to feel they have no responsibility for the continual downplaying of the war in Gaza and the means of its prosecution, ad it is on this grounds alone I value the many Jews who stand up to be counted. However, there is another reason why it matters when the protest is from Jew. It challenges the right of the Israeli Government to speak for all of the world’s Jews, of the past or recent diaspora of that world-significant ethnic group, and it challenges the view that the responsibility for stopping Holocaust and / or the beginnings of genocide, even putatively and collaterally, belongs only to Jews and about specifically Jewish issues and are focused alone on the sacrosanct nature of a Jewish State continuing to function in its present form and role.

There is much you need to treat with care in this topic because not only Abu Saif has been accused of being not only antisemitic but a Shoah-denier (someone who disputes the historical reality of the Shoah) but also other intellectuals, Arab and otherwise, including Pankaj Mishra. I mention him because he recently wrote a brilliant essay called The Shoah After Gaza in the 21 March edition of The London Review of Books.

Pankaj Mishra

This essay is superb not because of its politics, though its politics seem finely tuned to using evidence from history (including a balance of voice types) in ways that expose its own potential biases. The method in historical writing is called reflexivity. For instance, he tells us of the tendency to ‘reverent Zionism’ that emerged from his upbringing in a ‘family of upper-caste Hindu nationalists in India’, explaining that both attitudes to the primacy of the nation-state as the symbol of a group’s freedoms ‘emerged in the late 19th century out an experience of humiliation’, in both cases as it were by white Europeans.[2] Of course, Mishra’s understanding of that emergent ‘muscular nationhood’ is one he rebelled against, not least its patriarchal and masculinist ideological cover. But, such experience aligns him very strongly with a refusal to accept that anyone or anything that merely claims to do so can truly speak for all the voices of huge diversity within a defined group, be that Jewish or Brahmin.

Hence Mishra seeks out Jewish voices from history that refused both to be silent about the Shoah but also to show that states like The Third Reich emerge when people adopt a lax attitude to state power and its capacity to implement racist policies, including those virulently anti-Semitic ones of Hitler. He starts with Jean Améry, who though he urged caution in any critique of Israel in its emergence, eventually warned, in his own words, other ‘Jews who want to be human beings’ to join him in ‘radical condemnation’ the use of ‘systematic torture’. The torture methods were learned by the IDF of course from the period of the British mandate in Palestine, but Améry insisted that no nation is exempt from critique when it infringes the right to life, freedom from imposed pain without consent and dignity: “Where barbarism begins, even existential commitments must end”. This is strong stuff.[3]

Other voices were equally strong, and were backed by relevant experience of the effect of the Shoah on Jews, but these were often shouted down by politico-military leaders in Israel like Menachem Begin. According to Mishra, Begin began to weaponise the Shoah as a means of raising Israel as the solution to such an event ever happening again under the slogan ‘Never Again’, and in so doing writing Nazi oppression in ways that omitted admittedly smaller quantities of others exposed to Nazi barbarity, like European ‘gypsies’ and gay men, and patriarchal state-building. And with that went a presumption that Israel was exempt from scrutiny of its own state-and-militia based autonomy in relation to populations it saw as in the way of achieving a secure Israel. To that end, critique of Israel would have to be seen in the log duration of historical change of attitudes as anti-Semitic and aimed at all Jews wherever they lived. Begin, after all was humiliated, Mishra tells us, by Ronald Reagan (hardly a left-wing firebrand) called the killing of ‘tens of thousands of Palestinians and Lebanese’ and the destruction of Beirut a propagation of ‘a “holocaust” and ordered him to end it’.[4]

Of those ‘other voices’, Mishra instances Primo Levi, another supporter of a democratic and inclusive state of Israel in the Middle East, who protested at the same time as Améry about torture in Israeli prisons, going as far as to say: “we must choke off the impulses towards emotional solidarity with Israel to reason coldly on the mistakes of Israel’s current ruling class”. He detested, and he had the right, Begin’s use of the Shoah as a propaganda tool. But even to think this was to become a signal, because it was made so by a powerful machine working on legitimate Jewish fears of being as undefended by anyone as they were in The Third Reich of being a ‘Holocaust-denier’. Levi clearly was not that, but then neither is Abu Saif. Both merely point out that being Jewish does not stop Israel from adopting the very processes of thought of their past oppressors in other states and localities. But as Mishra says: ‘Misgivings of the kind expressed by Améry and Levi are condemned as grossly antisemitic today’. In 1993 Yeshayahu Leibowitz won the Israel Prize but he never stopped warning as he had done from 1969 ‘against the “Nazification” of Israel’.[5]

Mishra’s cultural analysis is a rich one and not one I can summarise without pointing you to the essay itself (available on the web). He like other anti-colonialists, like Frantz Fanon and Nelson Mandela, linked the struggle over Palestine to colonial struggles worldwide. From at least 2006 Mishra notes voices beginning to see in Begin’s propaganda policy a tendency to ‘instrumentalise’ the Shoah to, in Jewish historian Tony Judt’s words, ‘to excuse Israel’s behaviour’.[6] Strangely enough that very tendency also worked collaterally though not as its intention to salve the conscience of Europe and make allowances for former Nazi collaborators to continue their careers and to lift the complicity with Fascism from the German people and collusive states. The argument is too detailed to be reproduced but a central focus of the shaping of Jewish consciousness around the inviolability of Israel, especially in the USA, was that ‘the Shoah was a present and imminent danger to Jews’ and that this belief system became the basis of ‘collective self-definition for many Jewish Americans in the 1970s’. It is only thus, I think, that one can understand the genuine fear English Jewish populations that a Corbyn victory in the 2019 election predicated the possibility of a new British Shoah.

One cannot but understand this fear. However, this is not because it reflected a genuine threat of that sort. To say so is beginning to be a new, and ridiculous, definition of Shoah denial. Shoah denial is real but it has most promoted as a view of history by precisely those historians who supported the ‘social-Darwinist lesson’ that Mishra shows Israel now indulging in , that argues for ‘the survival of one group of people at the expense of another’. In such circumstances Israeli politicians ‘have resolved to prevent a Palestinian state’ and enjoy what one poll estimates as 88% popular support in Israel for maintaining the present extent of casualties in Gaza.[7]

This is dangerous; more so than it was at the time of Levi’s warnings. We must not forget the Shoah and the young people in the Jewish Voice for Peace, who Mishra calls ‘brave’, the appropriate slogan is still about holding the memory of the Holocaust alive, as Jonathan Glazer does in The Zone of Interest (see my blog on the film at this link), but in order to see it as a means of protecting humanity in all its forms. Their slogan is still ‘Never Again’, as promoted by people who believed a strong military state of Israel was the guarantee of that, but extended to: ‘Never Again For Anyone‘ and with a critique of militarism as the basis of Middle East state building.

At the moment the politics of the Middle East is toxic for many, perhaps most. This is not the fault of Jews, and Jews do count as an oppressed minority still, but it is the effect of a state that will stop at nothing to survive exactly in its present form and without change of discriminatory internal policies and dependence on a history and a resurgent policy of dispossession with violence. There is non-state based violence from some Arabs too of course – terrorist minorities – but their popularity amongst Arabs can only increase if we allow them to appear the only HOPE for Palestine.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Ruth Lawes (2022) ‘Miriam Margolyes and David Baddiel clash over whether Jewish people should talk about Israel’ In the Metro (Nov 22, 2022, 10:04am|Updated Nov 22, 2022, 11:56am) online. Available: https://metro.co.uk/2022/11/22/miriam-margolyes-and-david-baddiel-clash-over-israel-17803639/

[2] Pankaj Mishra (2024: 5) The Shoah after Gaza in The London Review of Books (Vol. 46, No. 6, 21 March 2024) 5 – 10.

[3] Ibid: 5

[4] Ibid: 5

[5] Ibid: 5

[6] Ibid: 7

[7] Ibid: 10