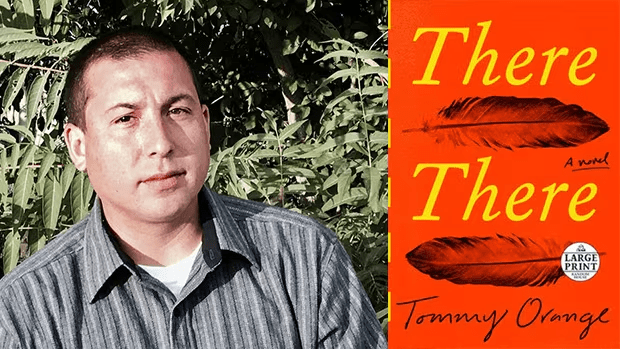

What Tommy Orange actually writes about his character Orvil Red Feather in his 2018 novel There There is:

‘… he stands, weak in the knees, a fake, a copy, a boy playing dress up… It is important that he dress like an Indian, dance like an Indian, even if it is an act, even if he feels like a fraud the whole time, because the only way to to be or not to be Indian depends on it’.[1]

Orange allows these thoughts to be prompted in his character, Orvill, the son of a single mother of Native American descent adopted with his two brothers by his grandmother, Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield, as a result of coming across an online definition of a Pretendian. However the term has a much wider wider resonance, the definition of which Wikipedia summarises thus:

a pejorative colloquialism used to call out a person who has falsely claimed Indigenous identity by professing to be a citizen of a Native American or Indigenous Canadian tribal nation, or to be descended from Native American or Indigenous Canadian ancestors. As a practice, being a pretendian is considered an extreme form of cultural appropriation,[8] especially if that individual then asserts that they can represent, and speak for, communities from which they do not originate.[3][8][9][10] It is sometimes also referred to as a form of fraud,[1] ethnic fraud or race shifting.[11][12]

Most definitions it seems are damning of a practice akin to a kind of racism where hegemonic cultures take over and use definitions of cultures they in fact oppress in ways that are harmful to those who have a more authentic claim to an indigenous identity. Yet academics now define what they call the ‘Pretendian problem’ and Canadian universities have rigorous policies in relation to such claims, which have themselves raised additional issues in relation to the fact that descent from indigenous populations in Canada is not obvious from racial markers in the appearance of the claimant of that descent – inevitably, given the racist pressures on indigenous populations to fragment and lose self-definition and self-regulation, ‘Indian‘ identity and appearance becomes layered with ‘whiteness’. A sample of the issue lies in a case study by Jessica Kolopenuk of her own situation as an academic. The following paragraph, gives a sufficient taste of the whole, with its specific academic jargon:

This case study is instructive because I am an Indigenous person who, like many, did not grow up on reserve and is multigenerationally dispossessed through previous Indian Act registration rules, residential schooling and the Sixties Scoop; but I am not disconnected. Stories about disconnection and family dysfunction caused by colonial policy tend to animate pretendian lore. However, despite colonial policies, my family, again like many, has always maintained our relationship to our family on and off reserve, to our territory and to our nation. My experience attests that you can be dispossessed and still connected through ongoing Indigenous relations beyond vapid ancestry claims alone. I make this assertion by also speaking directly to the experience of being a white-looking Indigenous person who takes seriously the responsibility of exposing whiteness as a system of power that conditions the possibility of pretendianism in academia.[2]

Orvil Red Feather is not a ‘case study’ nor does he treat himself as such. He is a character in a novel written to emerge in a reader’s consciousness as a boy attempting to come to terms, as the adult Tommy Orange continues to do in his novels – now at his second (one I am waiting to read), with a sense of a workable identity based on the whole set of his relationships with others. He realises that being a person is not unlike ‘being a character’ in the writing and ‘scripts’ of others and involves for him taking n the full weight of the impostor syndrome, feeling a fake as he attempts to be what he knows that he may only be enacting or performing. Hence the shadowing of the problem at the base of theatrical drama for the problem articulated by Hamlet is also articulated by Oedipus and other characters of Greek theatre, tragic and comic – that acting as one should be is being what one appears only to enact. Global culture has adopted the articulation of this problem in a a great white classic: Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and its central soliloquy, or its first line of it at least: ‘To be, or not to be: that is the question’. And that is our question prompt too:

If you could be a character from a book or film, who would you be? Why?

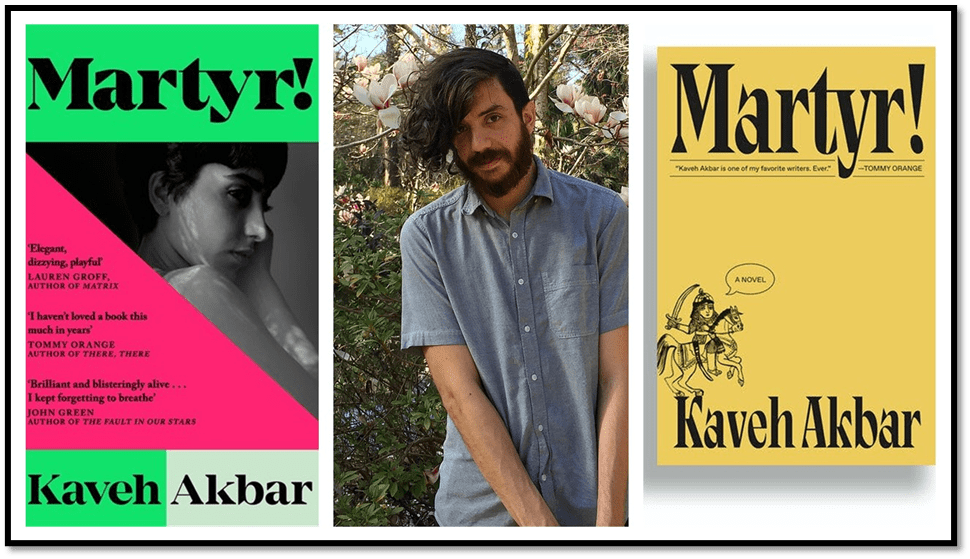

That I should find myself thinking of the character of Shakespeare’s Hamlet is hardly surprising for even great contemporary writers attempting to forge new genres from their specific socio-cultural and personal experience are doing so: none more so than Tommy Orange (a wonderful writer, about whom I will write specifically when I have read his new novel). Orange does it in part to explore how and why it is so complicated to just be, with or without making public claims about the definition of your being, an ‘Indian’ without also being a Pretendian. Orange has birthed an entire new generation of writers that also explore that issue by echoing Hamlet’s question: ‘the question’, as Mark Gatiss playing John Gielgud in The Motive and The Cue (see my blog at this link) says to Johnny Flynn playing Richard Burton playing Hamlet, calls it. It is mirrored by a wonderful debut novel by Kaveh Akbar (see my blog at this link) which is also about being an Iranian male, being queer and being identified by others and self as a ‘martyr’ in potential in his novel Martyr.

This latter novel ALSO mimics Hamlet’s dilemma throughout: as I say in my blog of a certain quotation: ‘ Who else could this ‘gloriously misunderstood scumbag prince’, than Hamlet other perhaps than the artist formerly named there as Prince’. [3] The playful reference to the great artist of modern music shows how wide the cultural grasp of this theme – and he, though a great musician was a spectacularly bad actor, even in Purple Rain (yes, I even wrote a blog on that artwork).

But before I leave the question of enactment in conditions of Terror, lets’s admit that no-one has quite understand it as well as Isabella Hammad in her novel Enter Ghost (my blog is at this link) which takes ion how a Palestinian woman must enact the role of her country’s representative whilst oppressive forces try to wipe out the role before it can be re-enacted differently, and which in this very day is being finalised in Rafeh, whilst the world pulls itself up on a front row seat to watch it happen and wring its hands rather than act in social justice.

I suppose that in the end I cannot answer this question for to imagine oneself as a ‘character in a book or a film’ is the condition of life, where people model behaviours on prior enactments and performances. Once Albert Bandura saw this as the basic cognitive element, which he called ‘modelling’ in Social Learning Theory, of character or ego development in children and it certainly is so in a nuanced fashion in G.H.Mead’s play and game theory of child development.

But whilst we are the subject of children’s acting, I remembered that, as a boy, I was fascinated by Laurence Olivier, but less his Hamlet than his awful hammy Richard III. I pestered my parents for a plastic sword so that I could limp about the limited space in our council house played the disfigured pretender and player king asking for a horse and promising someone, anyone, my kingdom for it (awfully easy when it exists only in a strange young mind). What awful lessons one must learn from the interiorisation of what people call ‘disability’ as character malformation from that kind of play. I can’t articulate it but it might be worth psychoanalytic consideration:

With love as ever

Steven

__________________

[1] Tommy Orange (2019 Vintage edition: 122, originally published 2018) There There London, Vintage.

[2] Jessica Kolopenuk (2023) ‘The Pretendian Problem’ in Canadian Journal of Political Science (Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 May 2023) Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique , Volume 56 , Issue 2 , June 2023 , pp. 468 – 473 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423923000239

2 thoughts on “‘… he stands, weak in the knees, a fake, a copy, a boy playing dress up… To be or not to be (what you would be or feel to be) depends on it’. The Pretendian in Tommy Orange’s ‘There There’.”