What do you wish you could do more every day?

We all have our own crosses to bear – obviously I am pathetically trying here to make clever reference to the wonderful cover of the hardcover edition of Steven Berkoff’s book, I Am Hamlet. However, it is true that I often feel like Hamlet myself, but don’t we all.

Nevertheless, I am thinking it more after a fine National Theatre production, that Geoff, Catherine, and I saw streamed at the Gala, Durham last night of Jack Thorne’s The Motive and the Cue – I blogged on my expectations of the production a little time ago (see that blog at this link). There is an issue about how we act – ethically – in Hamlet; as well as how we enact the things we truly feel live love, hate, or a mixture thereof in the world of real things. All of those things go round in the minds of the persons enacted by Jack Flynn and Mark Gatiss. And, in the play, all that is done at a remove from immediate experience because both of those contemporary living actors enact ones now dead, respectively Richard Burton and John Gielgud. Neither quite knew how they should act in any context of their lives it seems.

They expressed this self-doubt regarding some parts of their life (Gielgud repetitively so) in playing highly successful versions of the character of Hamlet in the eponymous play. These layers of what it means to ‘act’ in the world matter. I sometimes think (I think too much, I overthink – everyone says so, sometimes dismissively) at the expense of just doing something with a certain surety of action.

How does Hamlet express it in his most famous speech tackled in the Jack Thorne play, which is about the rehearsals of a dramatisation of a rehearsal of a production of Hamlet in 1964 on Broadway? There are layers within layers of acting that even extend to how Gielgud should act when he takes back to his Broadway hotel room Hugh McHaffie, a New York hustler. What Gatiss, playing Gielgud, thanks Laurence Ubong Williams, playing McHaffie, for is the cue the latter gives the former just to be cuddled and cuddled authentically in ways that comfort.

Of course, cuddling can be merely enacted without genuine feelings – can’t it? Is that why we think about the various levels of what is acted and what isn’t in our lives – holding back from actions we think inauthentic or doubting the authenticity of the actions of others. Hamlet holds back in every action, in expressing the complexity of his feelings to and about his mother, his father and step-father, his ‘girlfriend’ Ophelia, his supposed friends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and a real one in Horatio.

Hamlet, for one, says it all in that famous speech – and it resonates in the deepening layers of acting and / or enacting that are the basis of Thorne’s play. It is spoken by Johnny Flynn, Richard Burton and ‘Hamlet’ (whoever the latter truly is – or wills ‘To Be’). Do any of these persons do what they intend to do – including righting the wrongs they commit or are done in their name by the state they represent. Do they live lives not dictated by oppression or expected norms that they must enact? Burton did this in claiming, for instance, of having a loving father whilst repressing his knowledge of a real drunken Dad who abandoned him. Or is their action held back in the form of half-baked resolutions that never reach the fruition of an ‘act’ or action or ”acting’.

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought

And enterprises of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry,

And lose the name of action.

Hamlet Act 3 Scene 1, 93ff. available at: https://www.litcharts.com/shakescleare/shakespeare-translations/hamlet/act-3-scene-1

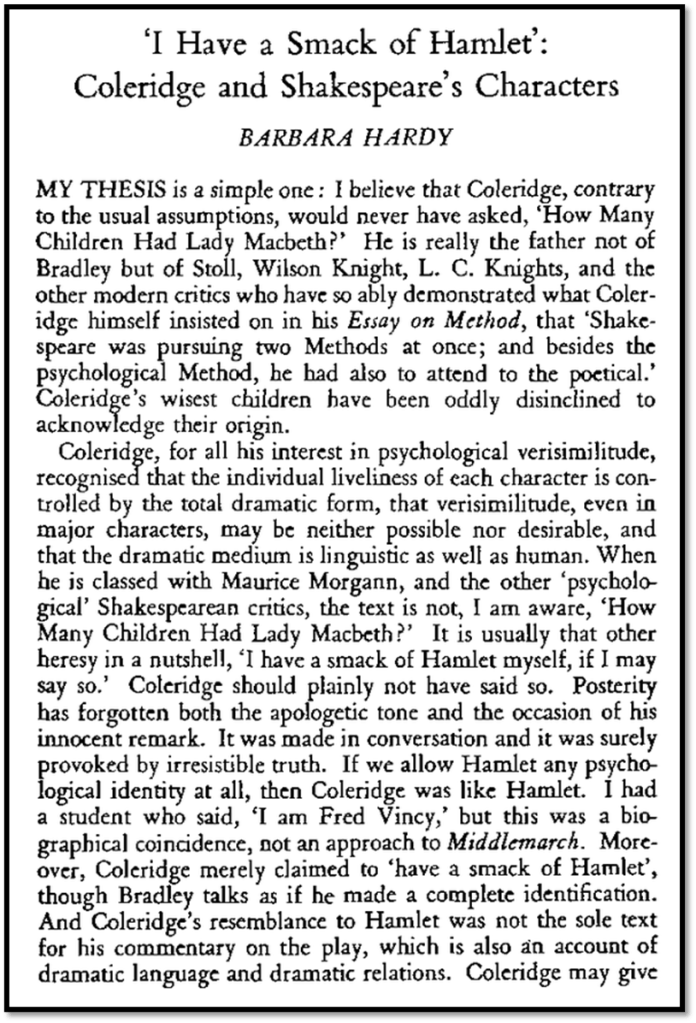

Even the introspective Romantic poet, critic and intellectual Samuel Taylor Coleridge, with respect of this line felt he had ‘a smack of Hamlet’, though the doyen critic Barbara Hardy in 1958 (I was 4 at the time, though I may have felt a little bit Hamlet-ish) felt it was only ‘a smack’ and not a full identification.

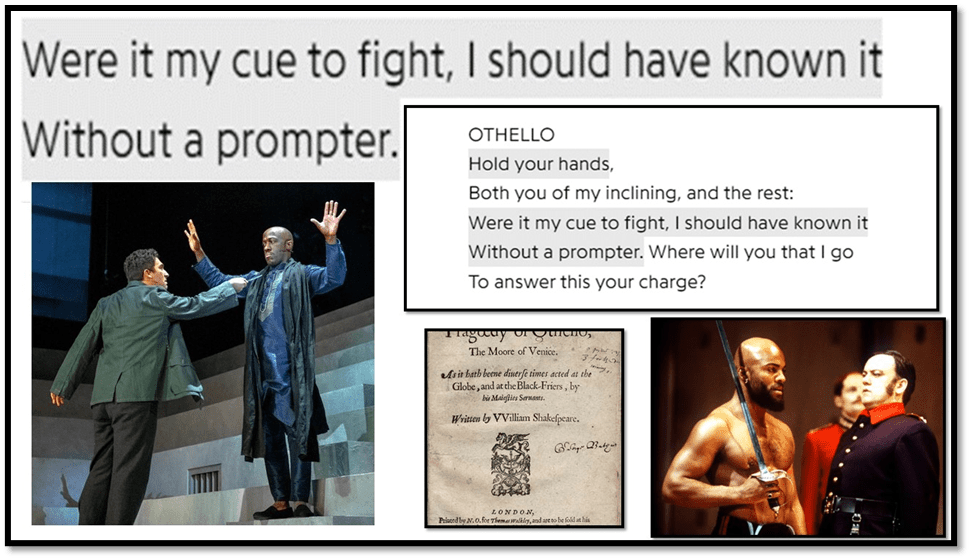

Hardy is possibly still correct, after her death even, in saying we go too far in looking for ‘real people’ in Shakespeare on which to cast our own personalities. After all, though, this issue of how to act is a human problem that no dramatist can ignore and will show in various characters. I find Othello’s version of the thought even more compelling – because I would like to look as ‘cool’ as he when he uses the motif of acting and cues, so prominent in Hamlet and drawn out by Jack Thorne’s play.

Othello is at his coolest in Act 1, Scene III (as in my collage below). There is no sickly thought here; just belief in patient waiting on a process you believe in, that will be clarified without the heat of action intervening, until that is it touches on your most possessive of feelings – you beloved wife whose actions and credibility you doubt. Othello’s coolness, however, lies in his belief in the justice of the state. And how wrong he is, even then! Nevertheless there you see it. Self-expression and action are conveyed by the use of layered metaphor that invokes the theatre in which alone the ‘action’ occurs – or is feigned.

It is a sticky thing that acting malarkey! What I loved about last night was the clarity of the dialogue between Gielgud and Burton, having both found ‘direction’ (a way of moving on decisively and the ability to be advised) from the circumstances they are in. Indeed, in this play, silently (as far as Burton was concerned in the play) true direction comes from a very wise Elizabeth Taylor played by Tuppence Middleton so supremely. This speech of Gatiss/Gielgud moved me. That is because it was delivered and enacted so well, and to cue, as it were (and hence I cite the italicised stage directions too). But it is also because of the silent acting of the receipt of direction by Flynn/Burton, after Gielgud has empathised with the child Burton’s pain at his abandonment by his dunk bully of a father:

BURTON … can’t quite look at GIELGUD. His soul is starting to be exposed too.

GIELGUD: The motive and the cue. Hamlet’s own words. The motive is the spine of the role – the intellect and the reason – the cue is the passion – the inner switch which ignites the heart. We can colour ourselves with limps and canes, with green umbrellas and purple suits, but we cannot escape the motive and the cue.

There’s a profound silence.

Jack Thorne (2023: 90) ‘The Motive and The Cue” London, Nick Hern Books.

That passagebof script puts a lot onto the actors – even the silence does that. I remember being taught by the peerless A.S. Byatt that we mistake ‘passion’ for a passive thing, something opposed to a binary thing called ‘action’. She argued that the derivation of the word from the word passio, a active verb in Latin, meant that suffering or endurance of soul or self was an active element (and she could have added, for she knew it and implied it, can be enacted without feeling or authenticity). The actors enacted it all – defined the very thing that acting was, even Flynn, who was an unknown quantity to me.

We will never be free of that dilemma, even in giving or accepting a cuddle from a man on the basis as McHaffie beautifully says that: ‘We all got mothers’.[1] What do men learn from mothers? They learn how to be loving or enact loving, and they learn about whether those things differ. And why, anyway, must men locate warmth in mothers, not fathers? It is all a dilemma of socially constructed life.

This was a beautiful evening of theatre, but it seemed a subject too for reflection on ‘What do you wish you could do more every day?’ For I feel I have the motive to identify and support justice, cutting through the barriers set against both by false notions of balance, process and control. Those latter things are things Othello believes in, in the first section of his play, before he fully absorbs the ways in which the racism of a white state is part of that process and will force him to identify with his stereotyping as a Black man by it. My motives may cohere and form a spine sometimes, but do I feel cued to action or cued to passive inaction, lost in being ‘sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought’.

I sit and fume as men of great passion like Jonathan Glover act (like the director of the film The Zone of Interest on the Holocaust – see my blog at this link). Glover is a Jew committed to other Jews, but is currently criticised as if he were an enemy of Jews. Likewise, I feel delight when, as reported in The Guardian, other Jews come to his defence, recognising that balance is a difficult thing to achieve and the control of cruelty, even passive acceptance thereof, must be fought, even when voices have to be heard from many locations and sites of suffering.

But ACT we must, and every day and more times than one in the day, even if this action is small compared to what Hamlet calls ‘enterprises of great pitch and moment’. We all owe it to ourselves to enact a better being, for that is the only way, by performance, that we will BE that better being in a way we find authentic without what Sartre called mauvaise foi (bad Faith).

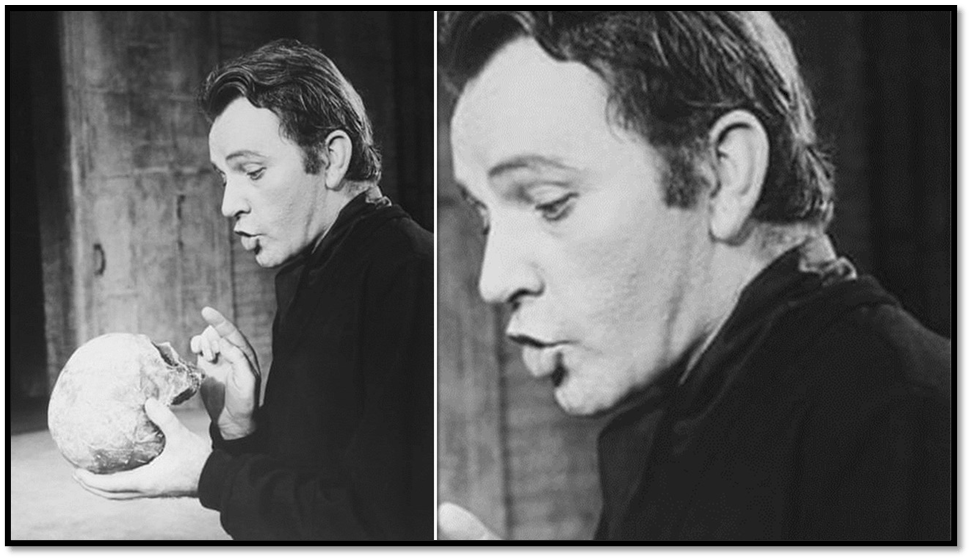

There was a puzzle I had reading the script of Jack Thorne’s play, about the intentions of his last stage direction: ‘BURTON … steps forward / He becomes a Prince. / He takes a deep breath. / Curtain‘.[2] Flynn did this brilliantly, though he took a step back and gazed at the skull of Yorick ‘prop’ as Burton himself is seen doing in famous publicity shots.

But there was in Flynn’s bearing both ‘spine’ of motive and eager readiness for ‘cue’ to enact what is necessary to enact without denying thoughts of our mortality. These latter inhere in the fleshless head he holds. These thoughts remind us that passion is action too and a prelude to better motive for it becomes a decisive motive. And if we act thus, we will act as Alasdair Gray intended in his citation of the following, though I have metamorphosed the word ‘Work’ into ‘Act’ (see my blog on the quotation at this link) : ‘Act As If You Live In The Early Days of a Better Nation’.

Thank you Johnny Flynn by the way for reinvesting this working class hero with the depth that underlaid his terrible hopelessness in his scarred and alcohol-destroyed life. RIP Richard Burton.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

_______________________________________________________________

[1] Jack Thorne (2023: 81) ‘The Motive and The Cue” London, Nick Hern Books.

[2] ibid: 104

3 thoughts on “I wish that I were more cued to ‘fight’ injustice (or act decisively at least). This a blog that reflects on seeing Jack Thorne’s play, streamed by the National Theatre, ‘The Motive and the Cue’ last night.”