In Martyr, an amazing funny fable, mythic in its proportions, about a queer American-Iranian former addict, by Kaveh Akbar, the main character, Cyrus, remembers an ‘old-school Muslim fairy tale, maybe it was a discarded hadith I guess, but it was all about the first time Satan sees Adam’. After surveying the first man thoroughly externally ‘like a used car’, Satan travels through Adam’s bodily interior from mouth to anus, concluding that God has made a thing that’s “all empty! All Hollow”, Satan concludes his job is now easy because: “‘humans are just a long emptiness waiting to be filled”’.[1] This is a blog about Kaveh Akbar (2024) Martyr London & Dublin, Picador.

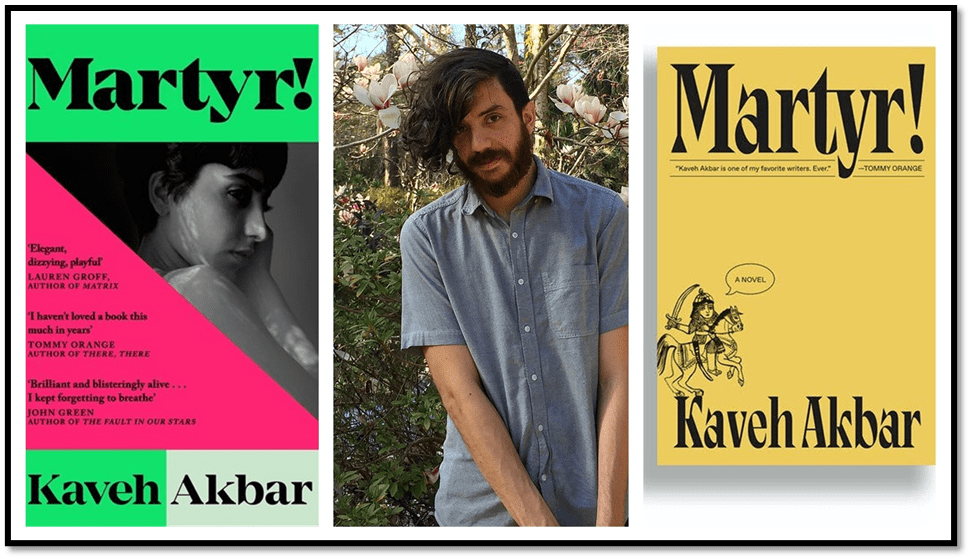

Left: the UK/Irish cover;. Right: The USA cover. Centre Photograph of Akbar in 2016 by Birbiglebug – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=130631043

Maybe if you read this blog, or continue to do so, after it turns into an exploration of some of the novelist’s wide reference to the margins of past and present cultures, you will have to just believe me that this is a story that not only matters in a world of intersectional identities and margins of uncertainty, but is also extremely funny. It is a kind of fabulous divine comedy, with some belly laughs in its visceral treatment of the body, its contents and excrements (especially piss) and the rationale for sex, alcohol and drug taking, with a basic commitment to truth and developing a sense f committed belonging in the world. It travels on a journey towards those commitments and is an ethical tale but at its heart there is a need, as part of its truth-telling, to embrace sexual and gender diversity, alongside diversities of almost every other kind. In the possible hadith mentioned in my title, Satan is merely the first of many who penetrate a human being just for the hell of it without needing to find meaning or pleasure in the process, for he is looking for the opposite and finds it. It is a novel for our times and is central because it explores exclusively the margins of being in order to infer the possibility of core beliefs that make life worthwhile.

The American critics seem keen on such adventures. For instance, Junot Diaz, an eminent writer in his own right, in The New York Times revels in Martyr’s profligate and burgeoning telling of stories by different characters in different ways and from different traditions and cultures. That is because in stories there are encounters that open up new ways of moving forward. Diaz favours the background stories told by the mother of the main character, Cyrus, named Roya Shams. Diaz describes her story as an adventure in sex, gender and sexuality where constraints open out to possibilities, for which a transliteration of an Urdu word is preferred, emkanat: ‘Dissatisfied with marriage, with motherhood, she stumbles into a friendship that opens her up to other horizons, to emkanat — possibilities’. Diaz concludes a review of the novel as a whole, which he calls ‘incandescent’ in his first sentence, thus:

Like Scheherazade, like all who are fractured and struggling to assemble the pieces, Akbar and Cyrus tell stories — beautiful, tragic, laughing stories — so that the unspeakable will not have the last word. If that is not emkanat, I don’t know what is.[2]

There is a clue here to why a critic such as Diaz and other first generation American intellectuals find the flavour of a novel told in a fragmented manner, with stories whose interconnection is not always clear or spelled out, where ignorance of how a story will progress and/or conclude is shared with the characters, even when they fail to (as in the case of Cyrus and his lover, of a kind, for Cyrus’ commitments shift with his obsessions). The young men usually prefer to ‘touch themselves, using their off-hands to trace the other’s nipples, Adam’s apple, lips’, or just hold each other in one bed because it: ‘was simple that way. Just two half-decent men sharing a blanket’. Zee, a rather wonderful white Polish drummer is unlike Cyrus is ‘openly and happily gay’ whilst Cyrus could be described as bisexual but largely by virtue of the contingency of who is available, since he ‘just ended up with people, their gender rarely figuring significantly into his interest’. Both have other sexual encounters or dates but ‘found it impossible to describe their relationship to others without over- or underselling the kind of intimacy they shared. So they didn’t try’. [3]

This world of a widely divergent and deeply felt individuality, to the point of layered connection AND simultaneous disconnection from others is also valued by Gabino Iglesias, an ‘author, book reviewer and professor living in Austin, Texas’. Both critics you will notice, if but by their names alone, will have lived on the margins of transculturalism, as is the common case in the United States, though unbeknownst to the vicious ideology of Make America Great Again (MAGA). Both are unsurprised to find the universal in the particular and also to find that which matters deeply and centrally in the shallow marginal offshore lakes where unnoticed but multitudinous lives are lived, in ways thought insignificant by ideologies of nation or unified culture, that is nothing but their ideologies.

Engaging and wildly entertaining, Martyr! will undoubtedly be considered one of the best debut novels of the year because it focuses on very specific stories while discussing universal feelings. It celebrates language while delving deep into human darkness. It entertains while jumping around in time and space and between the real and the surreal like a fever dream. It brilliantly explores addiction, grief, guilt, sexuality, racism, martyrdom, biculturalism, the compulsion to create something that matters, and our endless quest for purpose in a world that can often be cruel and uncaring.[4]

However, in the UK we don’t, I think, yet see life like that, even without being overly, or at least obviously, ideological about it. I struggled to find British reviews of the novel, though it is reviewed (behind a paywall) by The Irish Times, and probably elsewhere in the EC. The one I did find was in The Observer by Jonathan Myerson and is frostily ironic and damning of the novel’s and characters’ oddness’s throughout. There is no joy in ‘jumping around in time and space and between the real and the surreal like a fever dream’, as in Iglesias. Neither is their empathy for the marginalised – try, one might say to Jonathan, making a living as an illegal migrant in the nation you know to have shot down and incinerated a passenger airplane on which you know your wife was booked to fly in order to see her brother in Dubai. Rather we get this from him:

It might be clear by now that this is a novel that comes at you from every conceivable direction, some playful, some whimsical, others grimly intense. … Akbar includes poems. But there are also monologues from Cyrus’s lover and Orkideh’s gallerist, and there’s even a brief history of Iranian epic poet Ferdowsi. And while this disjointed, mosaic technique creates a kind of riotous energy, it comes at a price. Because, somewhat inevitably, Cyrus himself, dwelling insistently on what he calls “the big pathological sad”, begins to emerge as the least interesting, least energetic aspect of the whole confection. … When the final revelation – a genuine and well-worked surprise – lands on him, it lacks the visceral punch it deserves. It’s not that we don’t understand Cyrus’s anger and hurt, just that Akbar makes it hard for us to truly care.[5]

I think Myerson likes neither the ‘riotous energy’ nor the ‘disjointed’ or ‘mosaic’ in technique. He prefers novels which aim for controlled integrity, where energy serves to create characters we think of as ‘normal’ and ordinary human beings than the zanies we find here, as he presents them. There is no gainsaying that he truly finds Cyrus a character with whom he believes no-one can empathise, apart from the fact that the other critics I cited do just that and so do I. This is not however to say that Cyrus is not a flawed person, but the flaws resonate with life, just as much as do those of Oedipus or King Lear.

Indeed the main flaw in Cyrus is one Akbar goes to lengths to establish and it is like something Myerson misrecognises as carelessness in the author. I have never quite felt before that a trait in modernity has been so well captured by a writer as it is by Akbar in making Cyrus real to us: Cyrus may be a sham and pasteboard character as far as genuine passion is concerned, for most of the novel until its denouement, where even he does not know whether his feelings for things he says he finds meaningful are real or not. It is a trait so noticeable that a friend like ‘Sad James’ calls it ‘The Thing’. This will resonate into his conversations with the dying Orkideh (Persian for orchid). Indeed Orkideh, for reasons that we understand as deepened as we read on, wants him to quit looking for significance and meaning in her and ‘just be friends’ and ‘talk like regular people’. It raises this amazing self-reflection not unlike that in impostor syndrome, wherein Cyrus (named after a great King or two of Persia in the Classical Era of its Empire, a name feared by the Greeks) realises that his passions had something mordant in them: not meaningfully so but ones that get us nowhere:

… his whole life had been a steady procession of him passionately loving what other people merely liked, and struggling, mostly failing, to translate to anyone else how and why everything mattered so much.[6]

I have to admit to identifying, though elsewhere I think Akbar rightly recognises the trait as that of Hamlet in various buried references such as one noticed, though not named in that way by Iglesias when he illustrates writing that:

dances on the page, effortlessly going from funny and witty to deep and philosophical to dialogue that showcases the power of language as well as its inability to discuss certain things. This line about sobriety is a perfect example: “Beautiful terrible, how sobriety disabuses you of the sense of your having been a gloriously misunderstood scumbag prince shuffling between this or that narcotic crown.”

Who else could this ‘gloriously misunderstood scumbag prince’, than Hamlet other perhaps than the artist formerly named there as Prince. Certainly the idea of a prince unable to exit a ‘narcotic’ other than by going to another narcotic feels like Hamlet, as well as the addict’s Jungian and egoistic narcissism. Indeed he admits to being like Hamlet at one point, that other performative idealist pragmatic, living in his contradictions, thinking whether ‘To be or not to be…’.[7] It is that quality that Gabe (Gabriel perhaps) queries when Cyrus obsesses about Knowing what the ‘Higher Power’ is to whom one must submit in the Fifth step of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) programmes for quitting alcohol, when he says: ‘”Who cares?” Gabe answered. “To not-your-own-massive-fucking-ego. That’s the only part that matters”‘.[8] But it is deeper than the ‘confession step’ in AA, the tragic flaw (or hamartia [ἁμαρτία]) in Cyrus. Where I recognise myself is the awful sense in which, when the great narratives of coherent religious and political ideals fail you, you fish for them wildly unaware of how driven that passion is by deep insecurity in oneself: why we struggle to say why things matter but know they do. Here is an example where I see myself in toto, refusing reduction to the idioms proposed by others as Orkideh, proposes to him that of just ‘another death-obsessed Iranian man’, a thing more truly like vanity. After he thinks of what Orkideh says he turns to another obsession with which he gilds his life (and possible death should he be a martyr) with meaning:

So much of his psychic bandwidth was taken up with conflicting thoughts about political propositions. The morality of almond milk. The ethics of yoga. The politics of sonnets. There was nothing in his life that wasn’t contaminated by what he mostly called “late capitalism.” He hated it, like everyone was supposed to. But it was hate that made nothing happen.[9]

How much too of the politics of conscious woke anxiety is like that, what boils down in Cyrus to being on ‘the right side of history’ whilst never being agentive in its making. Mea culpa! Perhaps! But then how much of Twitter / X is like that.

One can see that Myerson has never seen himself like that – if he is an impostor (for who of us is free of feeling so) you can bet he doesn’t know it – or refuses to acknowledge it or goes for a course on positive thinking to get over it. Life however is not that simple.

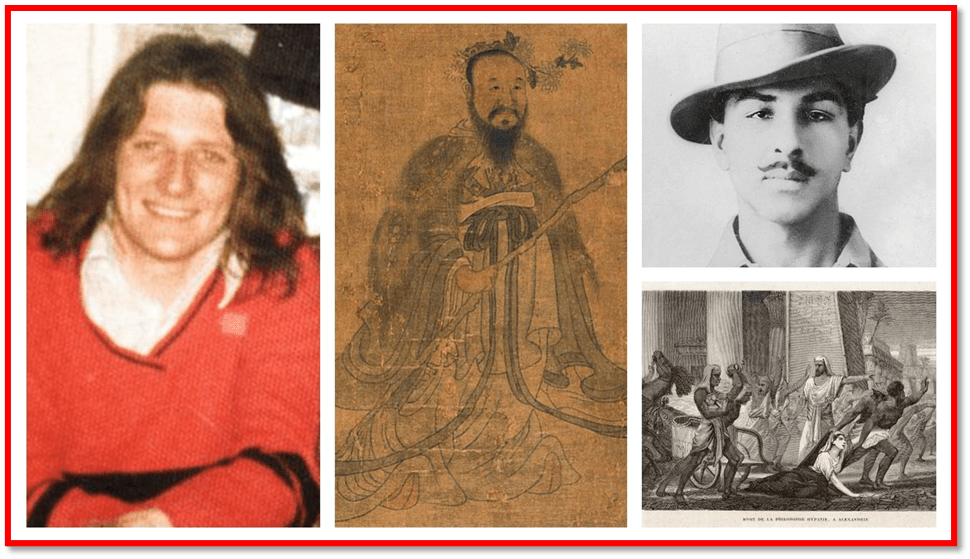

And hence why this novel is how its likers see it – a magnificent book about redemption of meaning that may not get there yet because we can no longer do so in our belated history, where the big stories that give meaning have been discredited. Myerson also has some distaste you will notice for the multi-directionality of the thinking and feeling fired at us in the novel. Like most he scorns anyone who might still revere people called martyrs like Bobby Sands, Qu Yan and Bhagat-Singh but like most he never mentions one claimed martyr for whom Cyrus has great passion Hypatia of Alexandria who is ‘type’ predicting the role of Orkideh, as spiritual and agentive mother with an intellectual life all of her own.

Left: Bobby Sands Longkesh Prison 1973 By http://www.bobbysandstrust.com/wp-content/themes/revolution_pro-10/images/bobby-sands-portrait.jpg, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31210546; Centre: Portrait of Qu Yuan by Chen Hongshou (17th century); Top Right: Photograph of Bhagat Singh taken in 1929 – when he was 21 years old. Bottom Right: Illustration by Louis Figuier in Vies des savants illustres, depuis l’antiquité jusqu’au dix-neuvième siècle from 1866, representing the author’s imagining of what the assault against Hypatia might have looked

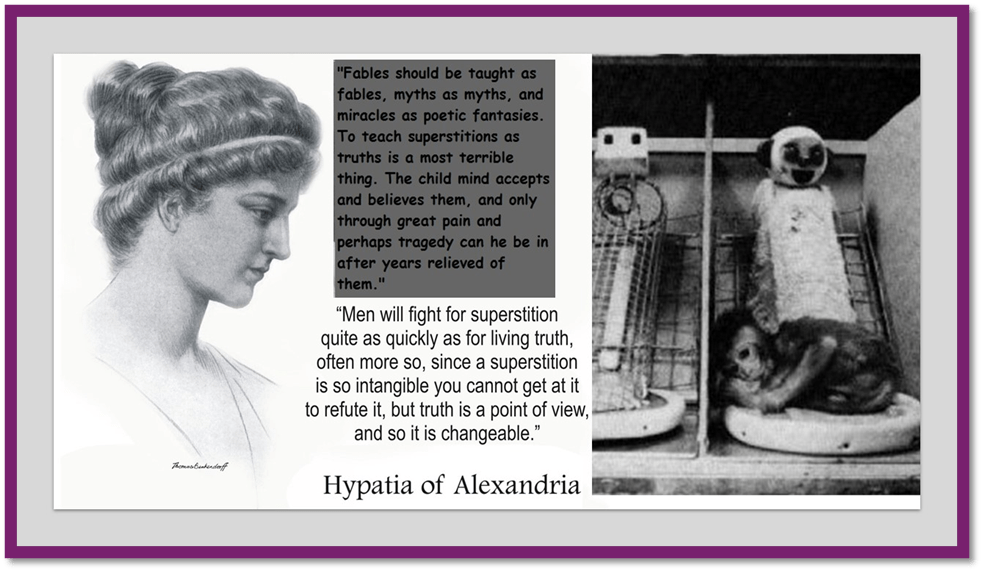

The poem Cyrus writes (or has written for him by poet Akbar) for Hypatia places her at the cusp of a moment where learning, thought and feeling begin to tear apart, fight each other, and East is divorced from West in world thinking, even in what we call science. The hegemonic West goes on to a cruel empiricism that cannot respect the life it studies, and the ‘sweet heaven’ that she studied as an astronomer is ‘already astrew’. Akbar characterise Western science by the Harlow experiments testing attachment to mothers of children using infant rhesus monkeys, their real mothers replaced by ones of wire framework, and the role of early separation (notably that is Cyrus’s story). Scientific thought becomes destructive (and male unlike Hypatia: ‘men pitiless as wire mothers’)and its ethical stances merely palliative, intensely certain and such thought is intrinsically alienating of minds from each other, in thought and feeling (replaceable if at all by drugs that might be uppers or downers and which addict the person):

It’s lonely here in the future

With all our drugs and knowing,

….[10]

Maybe too this condemnation of masculine hegemony is too much for Myerson and too unbalanced – hard to credit in the real world that he thinks he lives in. Yet there is truth in the domestic violence upon Leila, who had (unbeknownst to infant Cyrus) become her mother’s lover, by her husband Gilgamesh. It is she whom is the true reason for Roya’s flight to Dubai rather than a visit to her brother. I think there is truth too in brother Arash’s terrorisation of his baby sister in the early life. He laughs at her and taunts her for peeing the bed, whilst all along being the source of all that smelly piss, for as she awakes unknow to him one morning in 1973, she sees her ‘brother’s pants were unzipped; he was urinating directly onto her’. [11] Yer Arash too, like Gilgamesh and Cyrus has a name of men who sat astride Persian myth and history as great exemplars, not their baby sister’s body pissing on her.

And Arash too being without talents, either military or otherwise (“zero education, zero special skills, zero responsibilities outside of my country”), can in the war with Iraq ride around the field on a stallion persuading men to die without self-slaughter, aiding them in that holy refusal of suicide, by enacting an angel ‘of night, of history and death and of light and relentless fucking war’.[12] But before we conclude that this is adding to the mythology of Iranian male stereotypes of benighted and murderous men, we have to remember the key event in the novel – the historical shooting down by a rocket missile of Air Flight 655, originally booked for Roya and her son Cyrus before she found she had to leave him in Tehran because of his tender age.

Iran Air Flight 665: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran_Air_Flight_655

For Flight 655 was shot down by the USA on 3rd July 1988 by the USS Vincennes, about which it was claimed that it ‘did not purposely shoot down an Iranian commercial airliner’,[13] The myth of the ‘martyr’ / fighter is not an exclusively an Iranian one, though associated with the suicide killer, dying whilst bringing about a just cause, but its motivation is in the sense of human meaningless and the contingency of tragedies also involved in relations between world powers for domination like Flight 655’s shooting-down. And it is a product of the meaninglessness of a life without myths that work and motivate. For Akbar, it in part explains why, to escape the slow death of drug addiction, he turned to poetry, as now to the novel. Wikipedia has the following:

In an interview with the Paris Review, he cites poetry as helping with his sobriety, saying, “Early in recovery, it was as if I’d wake up and ask, How do I not accidentally kill myself for the next hour? And poetry, more often than not, was the answer to that”.[14]

And the beauty of this book is its knowledge of the import of story-telling as a means of knowing the world that has some integral but yet uneasy relationship with objective truth, as Hypatia is often cited saying. And hence my title quotation, here again:

the main character, Cyrus, remembers an ‘old-school Muslim fairy tale, maybe it was a discarded hadith I guess, but it was all about the first time Satan sees Adam’. After surveying the first man thoroughly externally ‘like a used car’, Satan travels through Adam’s bodily interior from mouth to anus, concluding that God has made a thing that’s “all empty! All Hollow”, Satan concludes his job is now easy because: “‘humans are just a long emptiness waiting to be filled”’.[15]

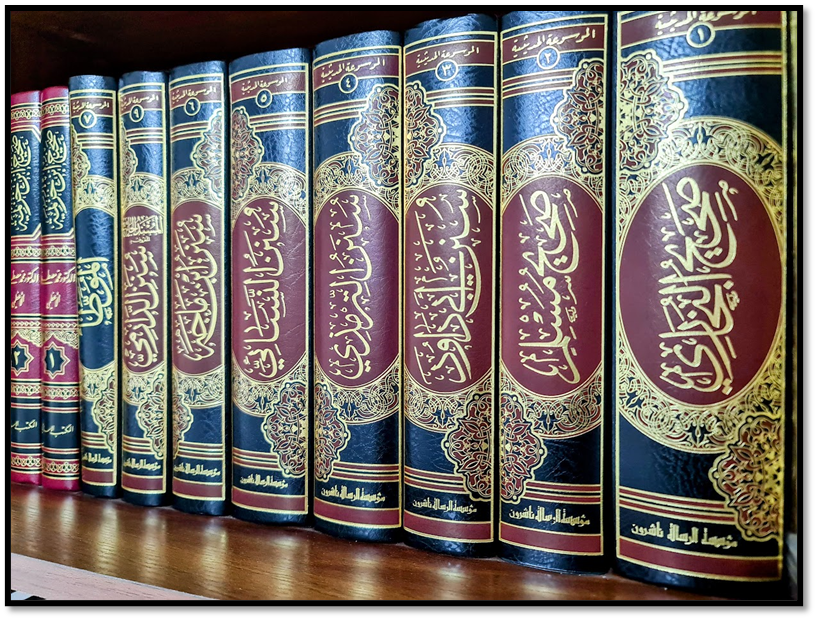

A culture of stories is at the base of Muslim traditions, as with the Scheherazade to whom Diaz compares Akbar. The hadith are often referred to and:

In Arabic, the noun ḥadīth (حديث IPA: [ħæˈdiːθ]) means “report”, “account”, or “narrative”. Its Arabic plural is aḥādīth (أحاديث [ʔæħæːˈdiːθ]). Hadith also refers to the speech of a person.

The hadith

Wikipedia says of them that:

Unlike the Quran, not all Muslims believe that hadith accounts (or at least not all hadith accounts) are divine revelation. Different collections of hadith would come to differentiate the different branches of the Islamic faith. Some Muslims believe that Islamic guidance should be based on the Quran only, thus rejecting the authority of hadith; some further claim that most hadiths are fabrications (pseudepigrapha), created in the 8th and 9th centuries AD, and which are falsely attributed to Muhammad. …

Because some hadith contain questionable and even contradictory statements, the authentication of hadith became a major field of study in Islam. In its classic form a hadith consists of two parts—the chain of narrators who have transmitted the report (the isnad), and the main text of the report (the matn). …[16]

I quote that at length to show the tradition from which the issue of the truth or falsity comes; the relative truth of witness statements, reports (like those from the US navy on the Flight 655) and narratives by people about themselves or other people. All accounts in this book are a kind of hadith, though only some are called so. In the novel, this theme runs alongside another; interest in understanding the role of the performative in the production of falsity, truth and a means of living meaningfully. Accounts are themselves a kind of performance and it is by performing differently that marginalised groups learn the limits of the powers that still constrain them. The only problem is if we allow the lives we live to remain untold by us in ways that offer us ongoing possibilities: such as the development of Orkideh into what she is, artist and queer woman (and likewise Roya though to her there has to be a twist in the tale). Arash is subject to the stories told by others and he suffers for it, as Ali, Cyrus’ father. And many people and groups of people allow their stories to look ridiculous in the eyes of others.

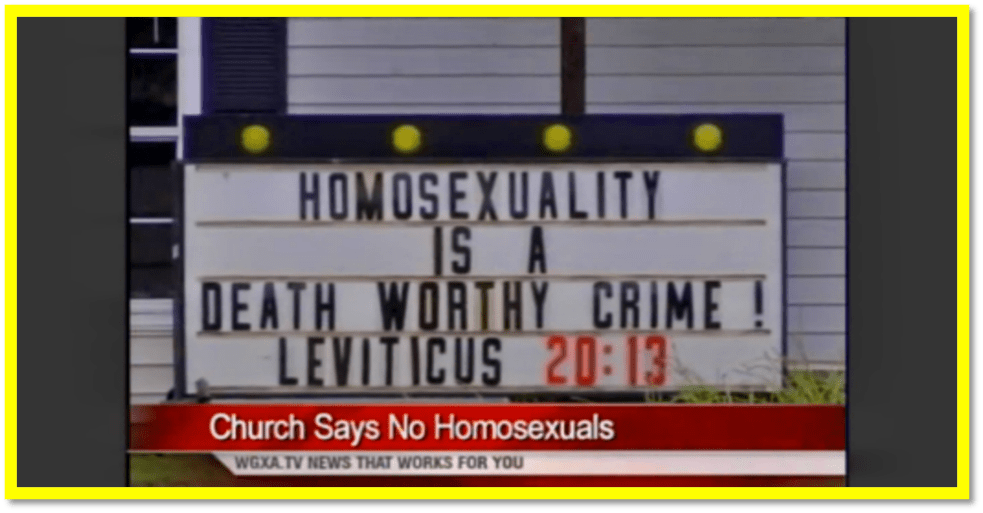

My own favourite aspect of this novel is its insistence that it must recue queer lives from stories that diminish the persons in them – stories told by clerics, doctors and people in other kinds of authoritative power over us. Cyrus must learn that it is not impossible to believe that there is a possibility that ‘Gay people are dying for love’. He will find that in reflecting deeply and with commitment on stories that touch him (his mother’s late released one).[17]

And what changes in Cyrus is also something about his grasp of sexuality and its links to both words and feelings and how that is performed with Zee Novak, to whom he will learn to communicate better. In his contact with Orkideh, Cyrus feels he can exclude Zee and fails to see his relevance to any learning that Cyrus is trying to acquire about himself. Hurt that he has been cut out, Zee says: “Seriously, Cyrus, what the fuck? Do you know who I am? Sometimes I feel you don’t see me at all”.[18] Something changes for Cyrus when he realizes that Hamlet was ‘full of shit’ as well as contradictions. And though he sees lots of others differently, what warmed my heart was this: ‘He wanted to take a long shower, to hug Zee, to spend hours curling into him, kissing the same spot on the back of his neck over and over and over’.[19] Zee will, we know, now finally be seen. For the first time we realize how this beautiful book could end up as apocalyptic, with the ghost of Arash returning to give them a vision of transcendence metamorphosed out of living nature by the end, an ‘illuminated rider’ on a ‘great black stallion’ because it is a love story between two men in passionate romantic union.[20] And arrangements between mates (who aren’t always partners for the purpose of regeneration) are as natural as they are performative but do not let is forget that nature is still full of possibilities that are ‘red in tooth or claw’:

Songbirds were darting almost imperceptibly across the sky, wailing broken half ballads back and forth to their mates. Two pigeons crashed into each other, then flew off in the Same easterly direction. A hawk was flying straight upward with a tiny starling in her claws.[21]

If Hamlet is ‘full of shit’, as Cyrus decides his indecisiveness makes him, then that may be because Satan in the hadith knows that people have to be full of something – and that if that thing is drugs or talk of empire then we will tend to illness and death without redemption. We can be full with something other than the desire of men to fight each other, for that only empties us in the end and leaves the canvas or page unpainted or unwritten, ‘blank’. Blankness is like hollowness and it is how Bhagat Singh leaves the world, Cyrus tells us in a poem:

all of us fighting like it still matters,

the blank canvas staying blank.[22]

Strangely enough what matters a lot in this novel is to know that what God you follow does not matter as long as it is not your own ego, including versions of it that are an ‘old bearded dude in the clouds who gets mad when I suck a dick’. Knowing God is like learning to love being in love as long as it lasts, which is never in one’s control (even mutually).[23] The artist that fills hollows and blanks is a performance artist making even the last of her presence, her death, into performance in the end, its only reality. Orkideh is after all as a fake newspaper report included in the novel, an artist in the mould of Marina Abramovic (for my blog on that artist use this link).

Do read this novel. It is a very important and beautiful one.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] Kaveh Akbar (2024: 304) Martyr London & Dublin, Picador

[2] Junot Díaz (2024) ‘A Death-Haunted First Novel Incandescent With Life’ in The New York Times (Jan. 19, 2024Updated Jan. 21, 2024) available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/19/books/review/martyr-kaveh-akbar.html

[3] Akbar op. cit: 151

[4] Gabino Iglesias (2024) ‘In ‘Martyr!,’ an endless quest for purpose in a world that can be cruel and uncaring’ in NPR (JANUARY 29, 20241:59 PM ET) Available at: https://www.npr.org/2024/01/29/1227116232/book-review-martyr-by-kaveh-akbar

[5] Jonathan Myerson (2024) ‘Martyr! by Kaveh Akbar review – riotous tale of a grieving son’ In The Observer (Sun 25 Feb 2024 09.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2024/feb/25/martyr-by-kaveh-akbar-review-riotous-tale-of-a-grieving-son

[6] Akbar op.cit: 155

[7] Ibid: 267

[8] Ibid: 28

[9] Ibid: 114

[10] Eleven ‘Hypatia of Alexandria in ibid: 117

[11] Ibid: 67

[12] Ibid: 169

[13] Cited ibid: 20

[14] cited https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaveh_Akbar.

[15] Akbar op.cit: 304

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadith

[17] Ibid: 302

[18] Ibid: 211 A lot changes

[19] Ibid: 267

[20] Ibid: 323

[21] Ibid: 322.

[22] Poem 17 Bhagat Singh in ibid: 175

[23] Ibid: 25

thank you for this post! resonated with me on a lot of levels and was really helpful to read the collection of reviews. Especially Diaz’ words spoke to me “there is dignity in our brokenness — sympathies and wisdoms that help transform a tale about a grieving young man and a senseless tragedy into a paean of life, of hope.” always delightful to find reviews & reflections on a book or movie that resonates with one’s own reactions to it, thx for that

two quotes from the book that encapsulate the process of addiction recovery for me:

1) “Getting sober means having to figure out how to spend 24 hours a day. It means building an entirely new personality, learning how to move your face, your fingers. It meant learning how to eat, how to speak among people and walk and fuck and worse than any of that, learning how to just sit still. You’re moving into a house the last tenants trashed.”

2) “The iron law of sobriety, with apologies to Leo Tolstoy: the stories of addicts are all alike; but each person gets sober their own way.”

LikeLike

The more I think about it, it seems a greater book and a true complement to his friendship and artistic relationship with Tommy Orange’s ‘Wandering Stars’. It is great because it elicits beautiful openness of public reflection that is helpful to everyone from good people like you. All my love. Steven.

LikeLike