What is one question you hate to be asked? Explain.

It feels like a classic meme, that moment from Scorsese’s 2006 film The Departed. I try and represent it above with some of the symbolism that shows why, once it has been said from above and in a threatening manner to the cop played by Leonardo di Caprio, we then see a close up of Leo in very deep discomfiture. Clearly, the reference to Shakespeare is meant to be part of the put down from a person who feels themselves superior to the other, but I think the question ‘What’s the matter?’ is a problematic one that often has a condescending tone – spoken as if coming down from above, and insinuating that there is little sense in what we hearing, especially if it articulates distress, complaint or suffering. It treats the ‘moaner’ with contempt. How the guy stands over di Caprio in the picture above tells us a lot.

In many ways the reference to Shakespeare has a precisely factual bibliographical theme behind it, for Shakespeare ever so often shows us that the question is condescending, sometimes extremely so. The classic occurrence is in a play fewer know than know other plays, Coriolanus. As the play opens the populace of the Roman Republic are in mutiny because of bread and food shortages (ring any bells with Tory Britain?). The patrician class, represented by Caius Martius have no time for such uncomely rebellious thugs. See how he uses the question (he should be on Twitter/X – Elon Musk would love him):

… What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues,

That, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion,

Make yourself scabs?

(Coriolanus Act 1, Scene 1, 162ff.)

You could hardly make it more obvious that you despise the wretches that dare rebel against the authority of the Roman Senate, who are after all obviously, or so Martius thinks (like David Cameron) that in economic depression ‘We are all in it together’, despite the fact that the rich Senate are still living sumptuously. You are ‘rogues’ and your complaints (that you and your family are starving) are but a ‘poor itch’. What a wonderful way of ‘blaming the victim’ there is in that question, ‘What’s the matter?’ And one can, if enacting Martius, say those words with that tone that looks down upon those it addresses, as is done to the di Caprio character by director Scorsese.

Sometimes in Shakespeare plays the question has a patronising air that is not unkind, but not quite caring either and is only said when the person speaking is of superior class and status to his auditor, and with an intention of poking fun at that inferior, sometimes because you know something that he does not know. I think Shakespeare quote gifs often fail to be useful when you do not know this information, but surely even without it, the question and its elaboration into imagery, that mocks the person spoken to, surely tells us how patronising that question in fact is. Try the experiment, if you don’t know the play Much Ado About Nothing:

It’s a jaunty quote but it is cruel, even if in comic intention. In Much Ado About Nothing the question comes from the final scene spoken by Don Pedro, the King of Aragon, to his inferior, Benedick, who is in despair because he thinks his beloved (who in truth he hasn’t treated very well in the play) Beatrice, is sexually two-timing him with someone who is a better catch for such a lady. Don Pedro’s retainer, Lord Claudio, makes it worse by referencing Europa having sex with Jove, in the form of a bull (‘play the noble beast with her’ with ‘horns of gold’ are his formulations of this sex). It’s a question that rarely equates with equality.

At the moment, I am reading both parts of Henry IV to prepare myself to see Ian McKellen at Manchester next week in the play, amalgamating both, as The Player King, in which he plays Falstaff. I thought I knew these plays backward but did not recognise before their significant use of the question ‘what is the matter?’ to expose the fact that there is no ‘matter’ or substance in Falstaff’s boasting, in crime or acts of supposed honour. When Prince Hall apparently does not join the fat Knight in a criminal adventure in Gad’s Hill but is there in fact in disguise, Falstaff calls him ‘a coward’. Cowardice, however, describes how Sir John acts. The phrase occurs in this excange:

FALSTAFF: … A plague on all cowards, still I say.

PRINCE: What’s the matter?

FALSTAFF: What’s the matter? There be four of us here have ta’en a thousand pound this morning.

PRINCE: Where is it, Jack, where is it?

1 Henry IV Act 2, Scene 4, 154ff.

Hal can say, ‘where is it?’ with ease and condescension for he knows he and Poins took the money off Falstaff with ease, so keen were these four to flee two men, whom they will pretend to have been a multitude. There is no ‘matter’ to show – no matter in the form of money, or of more abstract things difficult for Falstaff to claim, like truth, valour or honour. The fun of the scene lies precisely in that ‘What’s the Matter?’ serves as a way for Prince Hal to show how he will justify the overthrow of Falstaff when he needs to regain the image of a true prince and truer King. The deeper irony of the play is that it is the image not the substance of a King that Machiavel Henry V will assume.

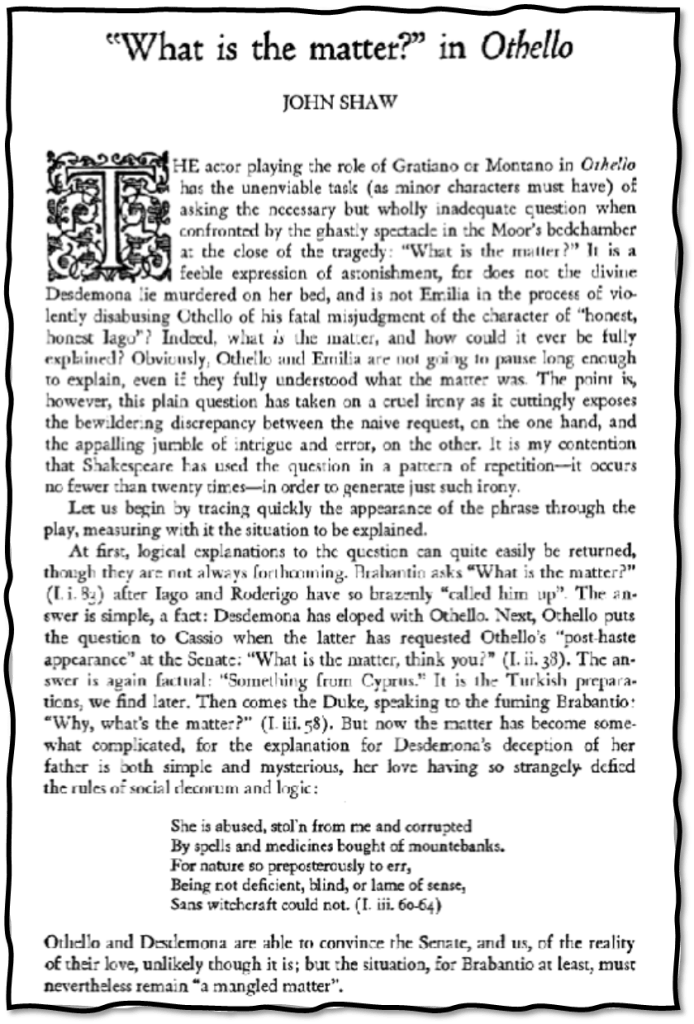

Let’s turn though to tragedy. In Othello the question is, according to John Shaw, writing in 1966, asked 26 times and gains a weight peculiar to that play where hard to decipher ‘matter’ often refers to the substance of a dispute in a state, a personal quarrel or the depths of a marriage and/or love/hate relationship. You can get a taste of Shaw’s argument from this first page from his article below:

But Othello is instructive too because, although this play also illustrates its use by powerful people to query others less powerful than they, we sometimes hear in it the fear that the status-quo-powerful feel of being usurped from their place, held as it often is with violence, often state-validated violence. Brabantio, Desdemona’s father, in Act 1, Scene 1, line 79ff. hears noise outside his house. It is a riot organised by Iago raising the well-chosen threat of ‘Look to you house, your daughter and your bags’, in order to ensure that Othello his commander is put under maximum pressure for overlooking him in the latest promotions of rank in the army:

What is the reason of this terrible summons?

What is the matter there?

Othello, Act 1, Scene 1, line 79ff.

How does the actor interpret those lines? Brabantio needs to show authority and condescension to those who break his peace, which, as with Othello using the question to break up a brawl in Cyprus, a little later, the state of Venice’s peace. Showing authority is easier when you appear from a window-balcony above them. Venetian imperial culture in the Mediterranean even looked blank and arrogant in the shape of its defensive fortresses with high walls looking down on subject populations of Greeks and Ottomans, or so I fancies, when I observed them in now abandoned ports in Southern Crete.

A Venetian fortress/ Palace in Cyprus

What Brabantio fears, Venice fears!. They both fear threats aimed at their colonial properties, racial purity via its daughters, and mercantile wealth. These are the threats Brabantio responds to when, equally condescending literally and socially, he asks from his balcony, ‘What’s the matter, there?’ In him, if not yet with Othello, it is as if the substance of any quarrel is a threat to his very substance of self or matter. ‘ What’s the matter?’, is as a question, always tinged with the fear the powerful have of having the basis of their power questioned or challenged violently or otherwise. If you ever have the misfortune to be the recipient of the question from a mental health professional, be on your guard and change worker if you can. As a worker in that sector, I found many of my colleagues used it, and always in a situation wherein they were consciously or unconsciously afraid of a service user, usually because of deep-seated biases and stereotypes of the ‘insane’, or other marginalised and labelled people.

Maybe, I learned my attentiveness to common phrases used with such polysemic reference because they are used to communicate consciously, and less so, a lot about how persons react to others in Shakespeare. The everyday interactions in Shakespeare live through the use of polysemic phrases, which surreptitiously do a lot of work in his peerless dramas, showing interactions in both social groups and dyads. If we doubt that Shakespeare did that, we need to use an exception that proves the rule.

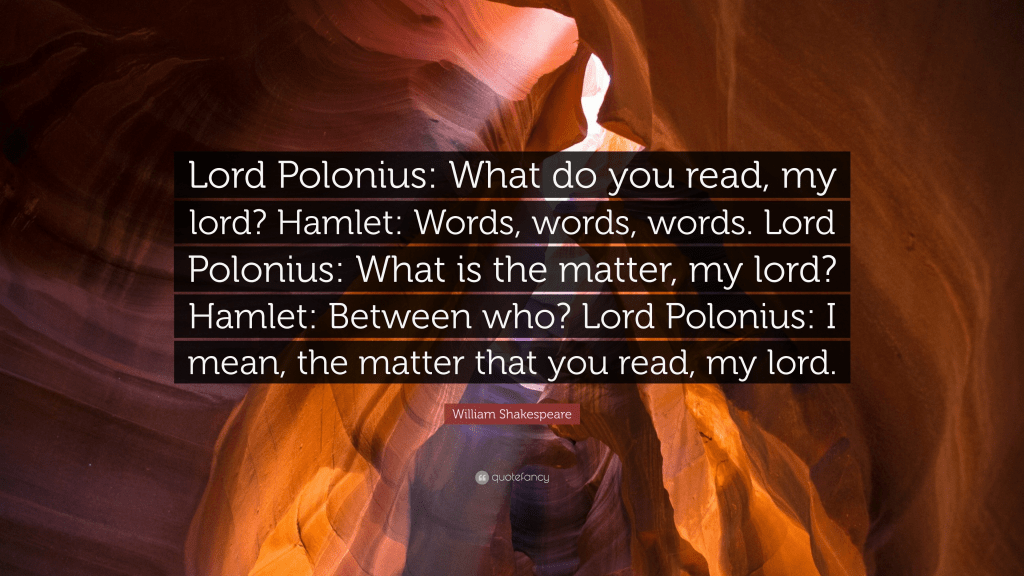

That phrase, by the way, is too often misinterpreted. It does not mean, as commonly interpreted, that there’s always an exception to every rule but rather uses the word ‘prove’ in an older sense, equivalent to the idea of testing by thought-experiment, a phrase that looks like an exception but may not be thus. It may seem an exception, for instance, that Polonius, an aristocratic retainer of the court of King Claudia’s of Denmark as he was of the late old king, Hamlet, uses it to his social superior, the Prince of that Court and heir apparent. Here is the instance in a gif.

But would Polonius treat Hamlet as superior, for he has known him as a child. Moreover, he speaks to Hamlet as people do, who think that they are sane, to mad people, keeping their questions plain and unambiguous and somewhat patronising. Shakespeare knows that Prince Hamlet is too clever for all this. He exposes Polonius to the truth that far from being a simple question, the question ‘What is the matter?’ is crazily polysemic in a number of ways. First ‘matter’ can mean the subject of verbal communication as Polonius intended it to be, but it can also be, as Hamlet interprets it in his reply, the subjection of contention in a debate or quarrel or at another remove an academic argument. Hamlet alerts Polonius that is, were Polonius intelligent enough to understand that alert which Hamlet knows he isn’t, that the Danish court he administers is riven by conflicts, often under the surface, and that these conflicts are the matter of the whole play, Hamlet.

Even when Hamlet reverts to Polonius’ understanding of the word matter, he uses it to mimic further a kind of way of talking that might seem mad to those believing themselves sane. And in doing so, Hamlet brings up to further notice more of the larger themes of the whole play – the relation of authority, youth and age for instance, and the problems of seeing time as a merely progressive movement, ‘if like a crab you could go backward’ (Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2, 204). But there is another facet of the dramatic polysemy here. That is because Hamlet knows that Polonius is a spy for the court of his mother and the usurper king, his Uncle, as well as a tender guardian of his daughter, the woman Hamlet once loved, Ophelia. In the very scene preceding this one, and before Polonius has received his orders from the Gertrude and Claudius, he used the phrase to his daughter to mean, what is the matter with you or what is your ailment that you look as you do.

POLONIUS: …. How now, Ophelia? what’s the matter?

OPHELIA: O my lord, my lord, I have been so affrighted.

POL: With what, i’th’ name of God?

Hamlet Act 2, Scene 1, 74ff.

At which point in the dialogue Ophelia describes Hamlet as if he were both disordered and out of all formal knowledge of the manners of a court (no hat and ‘his stockings foul’d‘) that he looked to her: ‘As if he had been loosed out of hell / To speak of horrors’. The case is a clear one, mental-health-professional-for-a-moment Polonius considers: ‘Mad for thy love?’

Hamlet knows then that when Polonius asks ‘What is the matter, my lord?’, he has another meaning. He wants, from the horses’s mouth as it were, an admission that Hamlet is mad for love of his daughter, a statement that that is his ailment – the cause too of deeper insanity and self-alienation, the ‘matter’ at stake. Not that Polonius doesn’t agree that Hamlet has taught him a deep polysemy around the original question, ‘What is the matter?”, for he has. He says of Hamlet’s talk:

Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t. … How pregnant sometimes his replies are – a happiness that sometimes madness hits on, which reason and sanity could not be so prosperously be delivered of.

Hamlet Act 2, Scene 1, 205, 208ff.

There is matter in madness, but the sane tend to distance themselves from it, judging it from a distance or in secrecy – Polonius will do this at his cost later from behind an ‘arras’, a good place in which to be stabbed as if a villainous intruder to the Queen’s bedroom. Polonius pays heavily for thinking the answer to ‘What’s the matter, my lord?’ is some problem in the person interrogated with this question, rather than a deeper problem in the politics of the courtly government he serves and in the traditions of courtly love within that court that kill his daughter too later. Hamlet has become aware of this deep matter’ by supernatural means that have fuelled his original suspicions of his stepfather’s perfidy and his mother’s sexual freedom so soon after his father’s death, but nevertheless he handles it messily, never getting to grips even with the true nature of the matter that disturbs him, which is the nature of being itself: ‘To Be or Not To Be’.

What’s the matter? To be asked it is to be diminished in the usual course of things. It seeks to blame you for disturbing people who think they are too powerful, too reasonable and too high and mighty to be part of the problem they think they are investigating. So if I get asked it again, I will turn the question back on the interrogator, using the full meme from The Departed but in a different way, for the question would be used by as an ironic reflection of the gall of the person asking it and repeating their words with sarcasm, if I have the courage to do so, which I doubt: “What’s the matter, smart ass, you don’t know any fucking Shakespeare?” Well, it’s easier than giving them this long blog to read. A rather charming guy on Twitter @BillyVacant keeps getting asked questions like this by his quantum of followers. so I will tag him in on Twitter.

With all my love

Steven xxxx

If anything ever is the matter with me, tell me, sweet people. That’s what the feedback service is for on WordPress.

أنصحك بقراءة مقلاتي من أجل أخذ المعلومات

LikeLike