Autofictions are fictional life stories that look like an autobiography and have autobiographical elements from the author but are told about the life of a fictional character. Some openings of both autobiographies and autofictions are a kind of closure as well as an opening. They assume a summing up of self in some take on, or about, one’s personal significance to others or oneself (usually in circumstances where you still think you can – or, at least, ought to try – persuade others to agree on that significance). My opening would be an autofiction, too, for no life has one understanding of the truth. It will go like this:

Why write me up’, said life to me: ‘I haven’t done with you yet.

Bamlett’s Hamlet: A Life that wasn’t yet.

When greater writers turn to consider their own lives in a fictive framework, they tend to be so aware of the role of autobiography as a way of excusing a life that ought to have been lived better or more coherently and without doubt as its to the ending to which that life wends. Laurence Sterne found all this so comical an idea that he had his alter-ego, Tristram Shandy, write a sentence so long and full of excuses for himself that it’s notorious for that very reason. He excuses, in particular, the potential in him never to do anything – but just to digress over it, never getting to the point, and the sentence even does that to itself, resisting its ‘full stop’.

I wish either my father or my mother, or indeed both of them, as they were in duty both equally bound to it, had minded what they were about when they begot me; had they duly consider’d how much depended upon what they were then doing;—that not only the production of a rational Being was concerned in it, but that possibly the happy formation and temperature of his body, perhaps his genius and the very cast of his mind;—and, for aught they knew to the contrary, even the fortunes of his whole house might take their turn from the humours and dispositions which were then uppermost;—Had they duly weighed and considered all this, and proceeded accordingly,—I am verily persuaded I should have made a quite different figure in the world, from that in which the reader is likely to see me.

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, also known as Tristram Shandy, is a novel by Laurence Sterne (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Life_and_Opinions_of_Tristram_Shandy,_Gentleman).

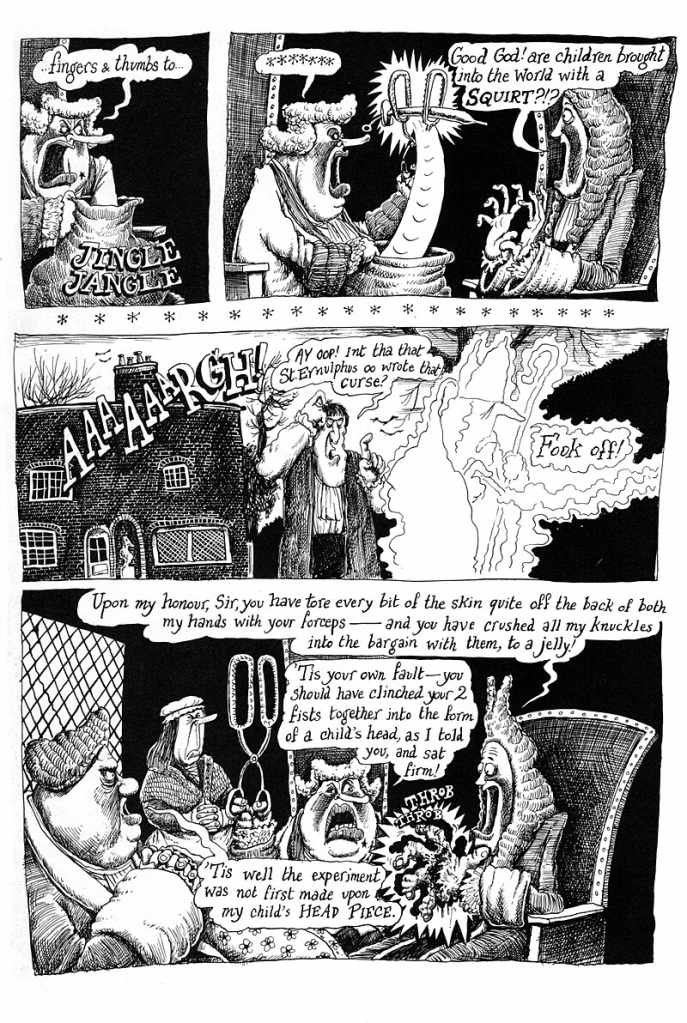

It gets nowhere that fabulous sentence and leaves everything still open, resisting closure in every sense and way it can. Even the reader’s response is, at best, a guess of what is ‘likely’ not what will be. And the tale goes on blaming Mum and Dad. Just like in Larkin’s most famous poem, Sterne, posing as Shandy, goes on to show how how your parents have already ‘fucked you up’ (in both senses of that F word) before you started by a description of their amazingly funny generative copulation that led to our ‘hero’, as in Martin Rowson’s graphic version below:

.

And while we are at it, look at Larkin opening that other autofiction, more often quoted than any poem, having entered our everyday phraseology:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

Philip Larkin, opening lines of ‘This Be The Verse’. Whole poem is at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48419/this-be-the-verse

Why should being ‘faulty’, as Shandy and Larkin’s lyric narrator are, matter, though? The Sterne novel says that by implication, since those human faults and flaws that are usually not spoken about, are the source of our interest in these lives and, in the Sterne example, faulty thinking gets him through a whole nine volume novel.

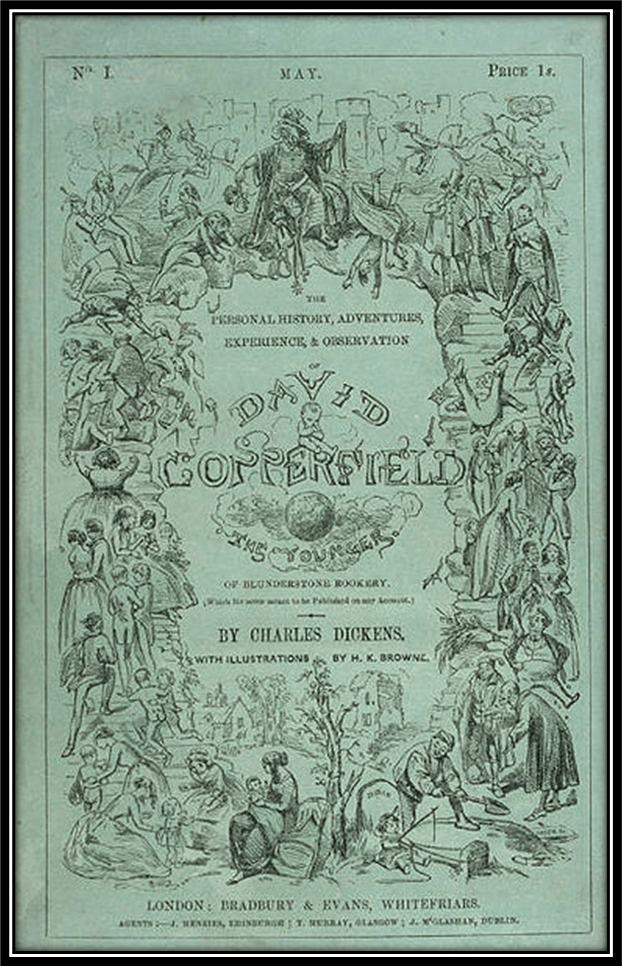

Charles Dickens, setting out to disguise his own life in David Copperfield, makes it much clearer that the point is that writers are posing a challenge to themselves as to whether their writing will measure up to their personal pretensions – or whether their ‘pretensions’ will be so fulfilled that they invent characters in its telling that are greater than their supposed author – as perhaps Wilkins Micawber (another writer’s Dad figure) or Betsy Trotwood already are.

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Copperfield

Perhaps the best example of non-closure by shifting from the start from the surfaces of self to a recording of one’s underlying significance as an illustration of life is in Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. The subject may appear to be the narrator but is, in fact, a search for something underlying the searching for the meaning of lives: the agencies of TIME in the mind and body both. In fact, this fact has led to an interesting set of speculations of how to translate Proust’s first sentence of his monumental novel of usually near-interminable but delicious French sentences. The first one is very short:

“Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.”

Richard Howard, a good translator says that in English he aimed for a wording to match his view that: ‘It seemed to me that what was needed was not only an opening phrase which would reveal the book’s meaning, but one that would begin with the word “time”, which would be the last word in the book as well, as it is in French’, as he said in an interview with George Plimpton in 1989. Here is a longer extract from The Paris Review‘s reprint of an except of that interview in an article by Dan Piepenbring in 2015.

RH: Three versions of Proust’s first sentence—“Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.”—have been published. The Scott Moncrieff-Kilmartin: “For a long time I used to go to bed early.” James Grieve (an Australian professor): “Time was, when I always went to bed early.” And mine: “Time and again, I have gone to bed early.”

GP: And what is the thinking behind your version?

RH: To begin with, “time and again” seems one of those cell-like phrases which sums up a meaning of the whole book, as long-temps does in French. I admire Professor Grieve’s “time was”, but it doesn’t have the notion of recurrence that I wanted. It seemed to me that what was needed was not only an opening phrase which would reveal the book’s meaning, but one that would begin with the word “time”, which would be the last word in the book as well, as it is in French.

Dan Piepenbring (2015) ‘I Have Gone to Bed Early: Translating Proust’ in The Paris Review (October 13, 2015) Available at: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/10/13/i-have-gone-to-bed-early-translating-proust/

Hurrah for Proust. In a novel so long, that yet appears to have only one subject (a ‘je’ who is also ‘Marcel’ and a disguised and transliterated heteronormative Proust) to the careless reader who is eager only to prove they have read it at all actually proclaims, according to Howard, that its hero is ‘time and repetition’, as that subject is also the hero of Freud’s Trauer und Melancholie (On Mourning and Melancholy).

And so then begins my autofiction: “Why write me up”, said life to me: “I haven’t done with you yet”. In a life with no closure is there no meaning or just a resistance to delusion (which usually means a longing for it beyond the capacity of human animal or machine measurement) that won’t give up and just ‘be something’. Go on, Stevie: JUST BE SOMETHING FOR A CHANGE!

All my love

Steven xxxxxxx