What experiences in life helped you grow the most?

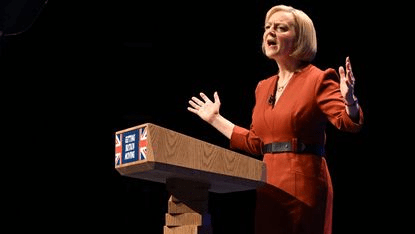

Do you remember this messianic moment in Toryism when Liz Truss announced her discovery of an ‘Anti-Growth Coalition’ in British politics and then forced her ideas into action causing widespread economic decline. The notion of ‘growth’ as the panacea of all ills ought to have had its day.It will hang-on longest in the current Labour Party, hide-bound by a mixture of ‘mixed economy’ fallacies derived from, but not as clever as, John Maynard Keynes. Social justice can, Keir Starmer thinks, only be bought by growth – and I use the word ‘bought’ advisedly, since reductive thinkers find it easier to talk about the market than the substances of people’s communal or even individual lives. Rather growth as a primary pursuit can be seen as the driving cognitive and physical force of the era of devastating man-made climate change, inequalities that widen daily and scarcity across the globe where most of the populations are most vulnerable, if not all.

In Psychology, the notion of growth was the baby of the existential humanist therapists, notably Abraham Maslow with his hierarchy of implied growth and Carl Rogers, who illustrated it constantly in terms of healthy natural images – rivers, including ones of blood in the arteries, that flow rather than dam up and healthy bodies developing maturely. The king of these thinkers: Csikszentmihalyi with his concept of ‘flow’ combined the sense of personal fulfillment with economic and social attainment. In a sense, though they all thought existential authenticity to be important, they fed the fantasies of capitalist ideology, whatever their abstractions about how growth is measured in altruism not egotism.

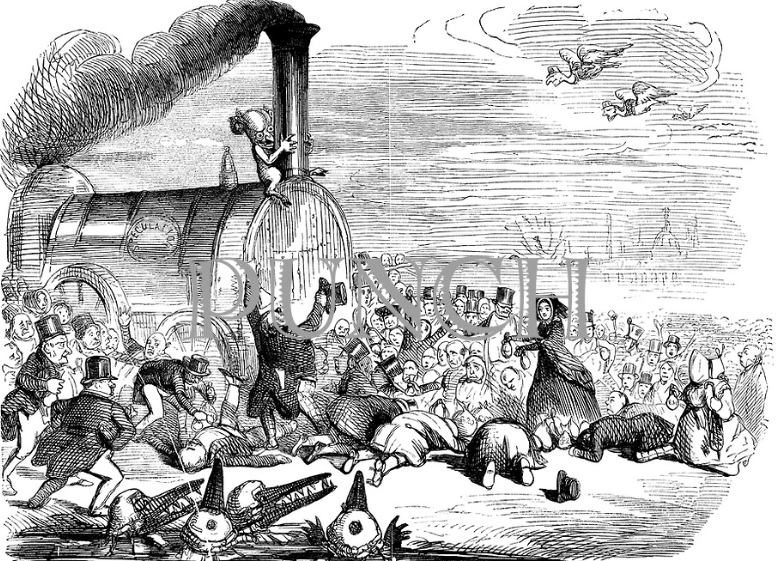

Personal psychology grew in ways that cut out any effective altruism by its admissions for the necessity and hegemony of self-interest. Helping others was a demonstration of self not an aim that stimulated cooperative mutuality. Growth was, in fact whatever the theorists said in increasingly unread books replaced by the dilution of counselling and self-help textbooks (a growth industry), a value in itself. What was meant was the growth of the individual – a concept justified though now more by Sartre and Camus than Daniel Defoe or other Robinsonade makers. Growth however still has need of others (and often of many others) – they are a resource for its exploitation as labour, or consumers or as reflections of personal power.No-one wants to be a Juggernaut that has no-one else’s bones to crush under its wheels, as was the point made (though of lower middle-class investors) in the famous Punch cartoon of the Railway-mania of the 1840s where the train represented the massive mobile icons of a people-hungry (as Victorian Imperialists saw it) Indian pantheon of deities.

In the 1840s, madness could be associated with the Satanic greed with which all parties in economic expansion involved, but it was also clear I think that this was ‘growth’ of a different nature from that of the body of an animal or a plant, Here was growth attended by demons of self-interest, represented (continuing the negative view of Hindu and other beliefs in the British-ruled Empire) by vulture-like entrepreneurs and crocodile-lawyers. The Juggernaut may be called ‘Speculation’, but the aim of dividing speculation from attempts of growth is always a division based on contingency. The hero of Tennyson’s Maud recalls the death by possible suicide of his father :

Did he fling himself down? who knows? for a vast speculation had failed,

And ever he muttered and maddened, and ever wanned with despair,

And out he walked when the wind like a broken worldling wailed,

And the flying gold of the ruined woodlands drove through the air.

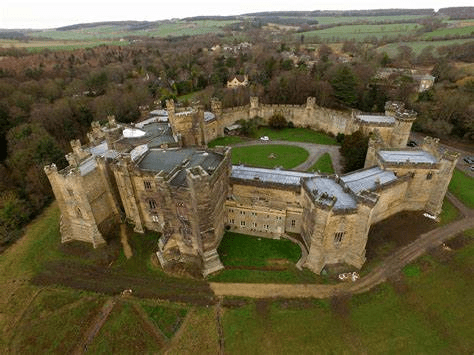

A ruined man indeed killed by a Juggernaut driving ‘progress’. The people of the poem, though not the completed suicide, was based on the Tennyson D’Eyncourts, relatives of the poet who from Brancepeth Castle (a Victorian Gothic folly caste near to me) ruled over the vast investments in coal production to feed the railway monster, in the less leafy Willington (I use its green and its monuments to dead miners as my blog masthead).

And the wealth of Brancepeth came from the pits owned at that sad place, Willington, which is even nearer to me. For its population growth was in no way a good, or at least not ambiguously so, idea, even if the pit owners had allowed enough space to allow it for the people at work in those Willington pits or in its shoddy and now cleared housing:

Growth is never an idea meant to apply to all. The working class were there to reproduce the wealth of the rich and to reproduce its own class, both at massive cost to themselves as men and women, for both birth and parenting could be as dangerous as the pit was. Imagine the Willington miner in the picture above wishing for growth, where even having enough to eat might have taken away his ability to do a nasty constricting job in thin seams of coal he felt forced by the threat of poverty.

In our modern economy growth is dressed-up as a means of both development onwards and upwards for individuals and societies. Yet the reality of how capitalism works cannot support such ideas as the continual cycles of recession show, and even if they could we now know at least some of the cost to the animal, plant and other elements of the environment (landscapes, water-scapes , atmosphere-scapes, and, the interior structures of all these, as well as the networked ecological systems they once supported). That full cost will still descend on us for chief amongst the Anti-Growth Coalition members are ‘extremist’ views of the needs of the planet – both major political parties in our insane system of government now support ‘middle-way’ approaches that do not harm ‘growth’ (as if they ever stopped doing). While such a position is endemic to the self-interest ideologies of the right, the falsely called centre-left has decided it is so passive to the world it serves, unable to provide either inspiration or true leadership in the true survival interests of most that it too has only ‘growth’ to offer.

Likewise the therapeutic community grows itself by mere repetition of formulaic versions of personal growth, bolstered by pretend versions of Ancient (usually eastern) ‘philosophies’ that have had the soul torn from them, much like the Dalai Lama. It boasts ‘mindfulness’ as a means of ensuring everything has any ideas about challenging the inevitability of paths to destruction by your behaviour, whilst not practising mindful exercise or raisin-chewing for ten minutes a day. In parliament, in the boardroom, in workplaces – all that matters is GROWTH not intellection and reflection on the way past, present and future are networked. Positive thinking becomes a shibboleth for conveniently forgetting anything but yourself. we are in a parlous spiritual state in this county – so much so that even people like me who believe the ‘spirit’ to be a construction of emergent qualities of the body, just like mind, mourn its passing as a concept. For ‘growth’ is also the name we give to a disease that we dare not call cancer, and growths can be be malign to life in other ways than being cancerous – some tissue growth can itself be dangerous without disease. But what grows and what does not is in part in our power because we have the power of thought and action related to thought, to praxis properly understood. Human beings grow and shrink selectively and in a way that in involves interactions in both directions of growth and shrinkage, emergence and disappearance. These processes are not linear. If we understood that simple thing, ageism, for instance,would die as would absurd magical thinking about personal significance and the tragedy of death.

What helps us develop is experience for good or ill. Tennyson experiencing the loss of the only person he ever truly loved, Arthur Henry Hallam, spoke of his own psychological and spiritual ‘growth’ as akin to the growth of the number of lyrics in his In Memoriam A.H.H., as he says in the poem’s Epilogue:

For I myself with these have grown

To something greater than before;

Epilogue: In Memoriam A.H.H lines 19f. Available at: https://kalliope.org/en/text/tennyson20020226132

But this playing with growth and being more not less is the most tedious part of the poem, though I agree bad experience and loss can foster helpful change, sometimes even belief that what you lost got most of its value from what you invested into it, or with which we cathected it. Sometimes we invest in the unworthy (as is the point of the Punch cartoon above) because we doubt our own worth too much and bolster that of those who shout loudest or manipulate appearances (there, I said that without mentioning that master of falsity, George Galloway).Tennyson said though that he in fact thought he overplayed the ‘positive thinking’ in In Memoriam and never truly overcame the suicidal ideation of his early poem The Two Voices, or the suicidal dramas of Maud. Writing of that Epilogue he once said: ‘It’s too hopeful, this poem – more than I am myself’. In fact he still feared human life, thought and beauty (even of poetry) was probably as subject to extinction as the dinosaurs were, and that even faith in the typologies of Christian redemption would go that way too. He added that he wished he’d added one more poem to make that clear. For growth that does not come to terms with the notion of ending is only growth in a physical sense – and even architectural, embodied or sculptured ideas of great size as the measure of all other kinds of greatness (even of abstract kind like growth of mind or spirit).

So I evade this question. We learn not grow from experience, and then only when we go beyond the appearances that experience sometimes manifests itself in. And learning is not growth, it is successive curation of time.

All my love

Steven xxxx