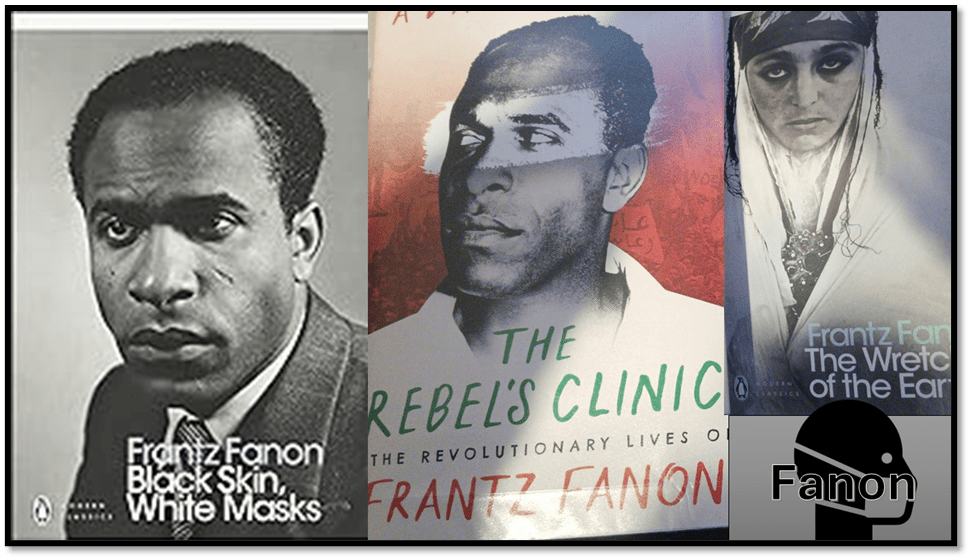

This is a blog that reflects on a fine biography, perhaps the best I have ever read of anyone, of Frantz Fanon. The book is Adam Shatz (2024) The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon London, Head of Zeus, Bloomsbury Publishing Co.

Frantz Fanon has fascinated me for a long time. I can’t remember when I came across him first. I thought it was at UCL as a student but I suddenly remember that it was perhaps not – it was perhaps as the result of a wonderful teacher of history I had in Grammar School, known for his devotion to Trotskyist ‘permanent revolution’ by selling Socialist Worker on the steps of Huddersfield Library and who helped guide my General Studies syllabus at A Level, offering a corrective perhaps to my love of F.R. Leavis, that grumpy reactionary, inspired by other hero, my English teacher. Belatedly he befriended my Dad and together they mourned their wayward sons, though both from a position of love.

Whatever the historical case, I was hooked and read that book translated as Black Skin, White Masks (which he wrote as Peau Noire, masque blancs in 1952). This book helped form me. Fanon was only 27 when he wrote it and it launched him into a confluence of writers who somehow worked within and influenced by very complex praxis-based philosophies that were then coming into turbulent confluence for the first time and tied together only by minds of individual genius: the praxes of Marxism, psychoanalysis, left Hegelianism and existentialism. I found in it ideas that predated other ideas in literary and cultural theory that were on the march to take over institutional thought, even in fuddy-duddy Britain, in the human, social and cultural sciences and arts by the 1970s. Fanon, though, unlike Jaques Lacan (they knew each other’s work), influenced us not only through books but in his roles in life – as a French citizen by virtue of colonial rule, soldier in the interests of what he saw as justice, as a psychiatrist and psychiatric institution manager and reformer (and potential abolitionist), leader in an anti-colonial opposition political force and its military strategy in a Muslim country he adopted but never quite adopted him, the, then French, Algeria. Later, outside it as a political exile in Tunisia, he also shook up mental health care in the Habib Bourguiba government.

Adam Shatz argues, as Megan Vaughan insists, in her empathetic review in the Literary Review for the ‘inseparability of Fanon’s political, literary and psychiatric activities’ but he did so, she acknowledges only by being also capable of being many things to many psychosocial and cultural movements that spawned the ‘many afterlives of his thinking and writing’.[1] And, on those afterlives Shatz is brilliant in his final chapter ‘Epilogue: Specters of Fanon’, which traces the different Fanons different people confronted as a result of filters such as political affiliation, beliefs or prejudices, or period of cultural fashion or fascination. This may be Fanon ‘chopped into little pieces’ as Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, his close ally, put it to Shatz, but it is necessary to know if you want to see how you yourself became part of the world of his considerable power of influence, often on the basis of partial reading. I found my own probable access point to developing my knowledge of Fanon in the section of the book’s epilogue dealing with ‘The Americanization of Frantz Fanon’.

This was a doleful period of Fanon’s afterlife, Shatz thinks, where the active political and working lives of the man and the relationships he valued most (‘Sartre, Césaire, Tosquelles, Abane’) were conveniently forgotten ‘in favour of his ostensible connections to Lacan, Foucault, Derrida, and other French thinkers whose work had spread through literature departments in the 1970s and ‘80s’.[2] Dubbed ‘critical Fanonism’, this is Fanon without the praxis connection, or one so etiolated it fitted only the need of persons thinking themselves ‘left’ academics to justify their own culturally marginal activities as ‘praxis’, without any sign of that affecting (or even taking risks with) their ‘entitlements’ in the status quo. This was I think a moment eventually of exit for me from the Fanon cult, as I stupidly began to see him too in that way rather than as a revolutionary thinker. He remained an innovative writer who exposed the supposedly private (in thought, behaviour and feeling) to hiz readers in order to understand the sins committed under that label and to find the political in the very genesis of the thing we call the ‘person’.

Shatz knows that the recovery of that integrated Fanon is a difficult task in a world that has changed so much, not least in the articulation of Black political consciousness, for Fanon was famously a ‘universalist’. He believed the term ‘Black’ (as the word ‘White’) when used to describe races or peoples to be an invention of colonialism, that had only meaning in the temporal sphere of politically conflicting interests. He never was, as far as we can understand from this book, a defender of ‘colour-blindness’, however.

He knew the latter was a tool of racism which pretends there are no differences instantiated around skin-colour in order to allow the hegemony of white power over ‘black’ people to prevail as a consensus of the superiority of what were actually ‘White’ values. That was, in part, because such values were disguised as an evolution in human values. But he also called out the falsity of what, in his day, was called ‘Negritude’, that set of values that valorised blackness of skin as an index of the past greatness of entirely Black value systems and often historical pre-slavery African states.

For Fanon, it was not about the binary labels black and white but about the present politics of colonial relations and their transformation into a yet unknown coming into being of a free or, as he called it, ‘disalienated’ human form.of being where the labels lost their binary opposition and unspoken hierarchy. He called that binary a ‘Manichaeism’. He spoke of colonial agent and colonizer psychodynamics, wherein the ‘native’, the ‘black’ and the non-conforming become the very visible presence of ‘evil’ against good, man against visceral animal:

The colonial world is a Manichean world. It is not enough for the settler to delimit physically, that is to say with the help of the army and the police force, the place of the native. As if to show the totalitarian character of colonial exploitation the settler paints the native as a sort of quintessence of evil. … the terms the settler uses when he mentions the native are zoological terms. He speaks of the yellow man’s reptilian motions, of the stink of the native quarter, of breeding warms, of foulness, of spawn, of gesticulations. … he commonly refers to the bestiary’.[3]

The term ‘disalienation’ Fanon uses of the process of his psychiatric, literary and political practice can’t be understood without remembering that the term ‘alienist’ is one that French psychiatry, despite the word’s past links to biological aetiologies of ‘madness’, could not, and still can’t, let go of. As Stephen Diamond suggests, alienism speaks to cultural alienations of the kind of magnitude caused by oppression and microaggressions in exclusive value system cultures which depend on the compliance of those with no effective material interest or gain from that system. For Fanon, this meant that he saw the main force of change in the truly marginalised: ‘peasants’ in the colonies and the lumpenproletariat, alienated even by the mechanisms of work in such a society and thus dismissed by Marx and Engels. His universalism was a kind of emergent quality which could not be used to mask the difference of power created by capitalism and colonialist imperialism and would live as long as they did, particularly the latter, which Fanon prioritised in order to redress the bias of the European and Soviet communism of the time.

Fanon’s universalism easily made him as affiliated to the freedom of the colonised who were of Muslim majority as to Black Africans or Carribeans. He became an Algerian citizen and may have been in the government of that predominantly self-defining ‘Arab’ nation had he lived. He embraced such fluidities identity politics because they did not name real things, only stages of being of a thing. He may have been flexible enough even to the cost of his ethics, given his felt guilt at his complicity, as he saw it, in the assassination of the radical Pan-African leader Patrice Lumumba in the interests of internal Algerian Resistance Force politics, of which he was the international ‘voice’ and constrained in that role.

He was hated and feted as a champion of the importance of violent revolution and disruption of colonial states. He rather rejected his own French Caribbean ‘heritage’ (if it can be called that and he would not do so) because his country had been peacefully ‘liberated’ by the French rather than won it like those colonies that had successfully fought with violence against French colonialism. Only the latter could be truly free, he thought. Indeed, Fanon thought his own birth-country, Martinique, was governed by the white-masked and self-nominated French black skinned people – to the cost of true political and cultural autonomy of thought, feeling and action and with the inheritance of the same forces of law and order as defined in White values that lead to the exclusion of the many.

But even here we find a fragmented Fanon: fragmented between the contrasting eyes of those who interpret the first chapter of his The Wretched of the Earth (called Concerning Violence) as friends or doubters. The first set included Sartre (who Josie Fanon, Frantz’s wife and more to the left than he in most accounts, believed to have ONLY read the first chapter of The Wretched of the Earth when he wrote his ‘Preface’ to it). After Franz’s death, Josie tried to have the famous ‘Preface’ suppressed, given Sartre’s recent capitulation, as she saw it, to the Israeli State in Palestine. Josie was no anti-Semite (she like Frantz based her thinking about colonialism on the analogy and differences of it with Anti-Semitism as theorised by Sartre and de Beauvoir). Josie was merely one of the first to protest the linkage of claims of antisemitism levelled against those who deplored the colonialist methods of the Israeli state, learned from the British, Americans, and the French. For Fanon the struggles of the Jew and those of the colonised were similar and different only in that the latter had found a homeland honoured by a deep but rather complex history of tribal land battles by virtue of being settled into it by British colonial forces and holding onto it with British and American means (arms in particular).

Some dub Fanon a terrorist apologist. In that light, interest in his thinking on colonialism has been fired in recent history by the war in Gaza still raging with British and American complicity in the arming of a very violent form of alienation of a whole people in that disputed land. The aim of Israel under Netanyahu is ultimate ownership, control and enforced regulation and settlement of the entirety of the region from ‘the river (Jordan) to the sea’, whilst people in Britain who claim this view of the conflict to be antisemitic (such as the current leadership of the Labour Party) pretend it isn’t but for a ‘two-state solution’. Meghan Vaughan found posters ‘going up in my part of London a few weeks ago advertising a talk on Fanon and decolonisation’. The interest is in his ‘insights’, she says, ‘into the plight of the colonised and the role of revolutionary violence’.[4]

Now this fact will operate in two ways. There will be those who use Fanon to justify the murders, rapes and hostage-taking of the incursion into Israel as a just reflection of sustained brutalisation of Gazan lives, others who use the talks to show another upsurge of revolutionary violence of the Cohn Bendit supposed variety that talk of Fanon as a terrorist apologist, himself accepting of brutal alienation of human values from the world of politics. And there will be another sort, like me, who look to Fanon to explain why ‘violence’ is endemic to the process and initiated by the means if violent colonial and land-grabbing means. For if we don’t understand the ‘violence’ we will be complicit, when we ‘condemn’ it, in condemning only that violence of the side least resourced in its ability to renounce violence. Brutal state sponsored violence has killed many times more people, including children (the highest toll in any war) than the original terrorist act and just as nastily, under conditions of ‘double-talk’ like that used by the French in Algeria and Vietnam (the latter talk inherited by the USA).

However, you need to read Shatz to see how well he helps us to see an integrated Fanon of many roles – mental health doctor, soldier, revolutionary politician, thinker, writer and leader (and even the somewhat homophobic and womanising sexual adventurer who some find hard to reconcile with their ardour for him). I certainly could not do justice here to Shatz’s achievement, for it takes a compelling and long book to tell the stories thereof – and the counterfactual possibilities even on the homophobia that Shatz deals brilliantly with. He speaks of talk with his colleague, the Jewish Algerian psychiatrist, Alice Cherki, who said that:

Fanon’s views on homosexuality evolved in a markedly less normative direction in Tunis, thanks in part to his work with a mentally disturbed gay man, one of the patents with whom he attempted a traditional psychoanalytic treatment. Whilst Fanon liked to hear himself talk, he was a keen listener in his medical practice, willing to change his mind in the light of the lived experience of his patients. [5]

Hence I listen less to the rather homonormative psychiatric asides about predatory white men in Fanon. Now this isn’t because they aren’t true because they may be, though few are queer examples. Moreover, many black men still validate such stories of white men and women, as I report in earlier blogs – see this link to a popular memoir account, and this to the wonderful Derek Owusu’s anthology of black male experiences.

What I do listen to in Fanon most is the way the belief in the Hegelian term, Erlebnis, used in Black Skin, White Masks, translated as ‘lived experience’, is not used as the limited method of knowing history Hegel felt it was but rather in the way later existential hermeneutic phenomenologists used it. ‘Lived experience’ is everything to this thinker, actor, doer, understander, and feeler of things below the skin. He was that rare thing – a psychiatrist who actually listens actively to their patients, as most only claim to do. Most neither listen or try to understand at all.

But I have always had a sort of barrier to falling in with Fanon entirely rather than with bits of him. I remember reading the words quoted below in Frantz Fanon’s Black Skins, White Masks whilst a student at UCL and thinking no-one ever spoke more plainly in arenas where controversy will always reign, not least about whether such words should be said, or even quoted at all. They have for long confused the hell out of my sexual-political development, as a white man committed for as long as I can remember to what I believed to be anti-racist action and politics.

We can now plant a milestone. For the majority of Whites the black man represents the (uneducated) sexual instinct. He embodies genital power out of reach of morals and taboos, … We have demonstrated that reality invalidates all these beliefs, which are based in the imagination, or at least in illogical reasoning’.

In fact he had established those facts thus:

So what is the truth? The average length of the African’s penis, according to Dr. Palès, is seldom greater than 120 millimetres (4.68 inches). Testut in his Traité d’anatomie humaine gives the same figure for a European. But nobody is convinced by these facts. …’.

Fanon’s insistence on our resistance to this myth matters. Note again the strain in actor, Obioma Ugoala’s (2022) The Problem With My Normal Penis: Myths of Race, Sex and Masculinity (my blog at this link given before above) or the treatment of similar issues in queer male relationships in a novel by Okechukwu Nzelu at this blog link. For I have to come clean that I think the white male does embody some of its impostor pathology in the borrowed idea of a ‘primitive’ man, who is marked as ‘black’ (or sometimes working-class as for E.M. Forster) and is therefore both an ideal object and simultaneously or serially a threat to that masculinity depending on the shifting dynamics of male desire. Hence, Fanon could say this in Black Skin, White Masks:

Fanon dictated his texts in ways that recorded his speaking voice, through an amanuensis he sometimes called his ‘tape-recorder’ in clinical cases, and we hear a voice here: as if the prose itself were forced to validate ‘lived experience’ (even that of Fanon himself) as meaningful evidence worthy of respectful analysis and reflection. With it, we get highly subjective impressions and ideas supported merely by his subjective account. It was important to Fanon to validate this process but it meant that what you got was valid only for the moment and with the moment’s passing authority within the dialectical process by which truth emerges – at least if you can get a word in edgeways and part Fanon’s turbulent flow of genius. And people who used his services could speak freely many witnesses report. But there is another reason for the pressure of speech (which Fanon would have been taught to recognise as a psychiatric symptom) in Fanon, which is that he knows voices saying what he says usually get silenced by an appeal to norms of public decency and reticence in behaviour.

To be disalienated, the force of diverse voices must be felt, including those willing to say what others want to keep secret, or ‘private’ as they prefer to call it. My own feeling is that Fanon is not wrong about how fantasies about sex and race congregate in myths that are resistant to reason, and which get magnified by media dependent on, or at least very open to, fantasy such as the popular internet and social media. And I have to admit that I have, in my history, found such fantasies in myself even whilst being able to attempt to regulate them. In the realm of a social construction with very toxic potentials like that of masculinity, this is hardly surprising. In masculinity, toughness, hardness, and primitive unleashed power have always formed an ideal in projected forms of masculinity, from Mills and Boons stories to hard-core porn and adventure stories. Fanon himself made massive play with the fantasies of Tarzan, strangely ’a great white hope’ myth. I have no doubt myself that the fantasies of Black Skin, White Masks could, like Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams be taken deep into Fanon’s own contradictions as a ‘man’ as well as a doctor, political activist and theorist had we the evidence to go on, and that Fanon was aware that was likely to be the case, for he knew he suggested even more than he spoke in telling stories about his lived experience, even as his clinical service-users did.

In the fifth chapter of The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon discusses the role of mental illness as a ‘reactionary psychosis’, a condition dependent on a stimulus that is for every Algerian involved, and he considered himself as such, he described as ‘the bloodthirsty and pitiless atmosphere, the generalization of inhuman practices and the firm impression that people have been caught up in a veritable Apocalypse’ that was the Algerian War of Liberation.[6] He says in the introduction thereof of the need to ‘bind up for years to come the many, sometimes ineffaceable, wounds’ inflicted by the war that is the essence of French imperialism:

That imperialism which today is fighting against a true liberation of mankind leaves in its wake here and there tinctures of decay which we must search out and mercilessly expel from our land and our spirits.[7]

There is nothing lazy about the first-person plural ‘our’. In Fanon’s psychiatry I believe there was no ‘them’ and ‘us’, although he had not the language yet to say so openly, for he still feared threats to his authority, already challenged by his status in the eyes of the colonial France which had enforced the heritage of its language upon him and which had moulded its white mask to his mouth. Fanon, too, is part of the wound that requires temporary suture.

Fanon, that is to say, knew, as I read him in Shatz’s brilliant book, that he was a casualty of colonialism as well as attempting to be a physician ready to cure ‘ourself’. And that wound widens. We still need him. A strong impression in this book is that the resistance to antisemitism, in Jews and non-Jews, was part of the answer to understanding racism against Black people and how it is confronted for Fanon and his circle. However, the yoking of any criticism of the Israeli state in recent times, heavily modelled as that state is on the imperialist powers that helped mainly to create and sustain it with huge armed forces, police and an antagonistic and predatory attitude to free expression of Palestinian culture (see my blog on Isabella Hammad’s novel Enter Ghost at this link), has meant that Fanon is best understood today as explicating the violent terrorism of HAMAS without justifying it.

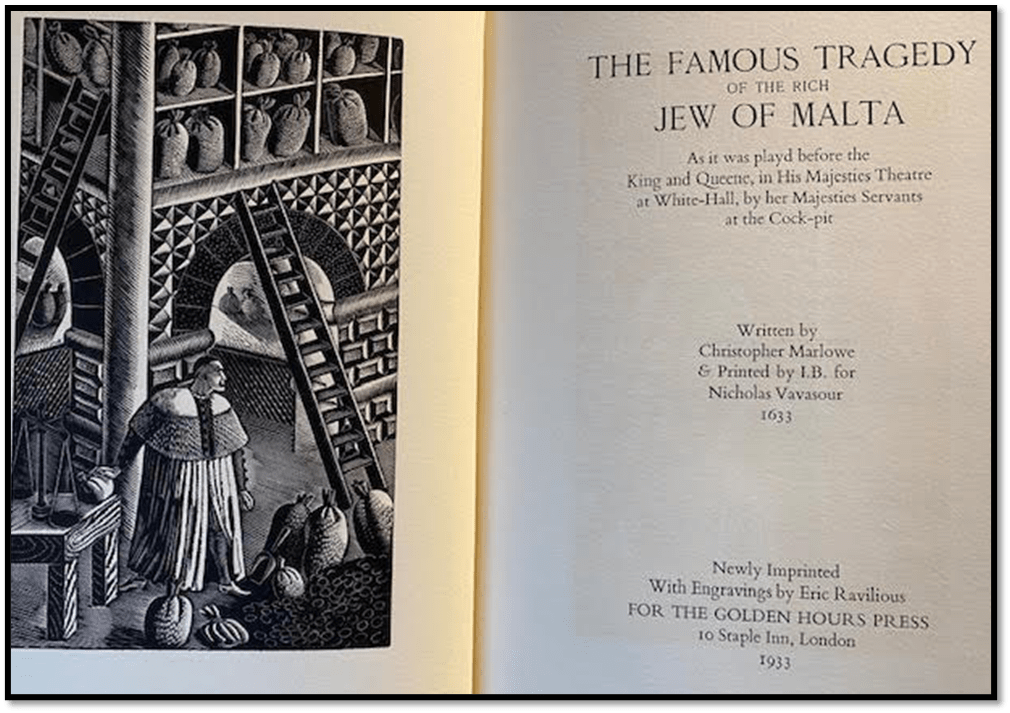

And I think the last phrase is important. The violent war in Gaza has killed more people than any past war, more children than any past war. To say so should NOT be seen as the need to repeat the trope of baby-killer Jews that has long been used in antisemitic literature. All those tropes are in Christopher Marlowe’s The Jew of Malta in the form of the boastful Barrabas, but they are clearly based on lies, which the statistics of child death in Gaza are not.

As for myself, I walk abroad o’ nights,

And kill sick people groaning under walls:

Sometimes I go about and poison wells;

And now and then, to cherish Christian thieves,

I am content to lose some of my crowns,

That I may, walking in my gallery,

See ’em go pinion’d along by my door.

Being young, I studied physic, and began

To practice first upon the Italian;

There I enrich’d the priests with burials,

And always kept the sexton’s arms in ure 80

With digging graves and ringing dead men’s knells:

And, after that, was I an engineer,

And in the wars ‘twixt France and Germany,

Under pretence of helping Charles the Fifth,

Slew friend and enemy with my stratagems:

Then, after that, was I an usurer,

And with extorting, cozening, forfeiting,

And tricks belonging unto brokery,

I fill’d the gaols with bankrupts in a year,

And with young orphans planted hospitals;

And every moon made some or other mad,

And now and then one hang himself for grief,

Pinning upon his breast a long great scroll

How I with interest tormented him.

But mark how I am blest for plaguing them;—

I have as much coin as will buy the town.

The Jew of Malta, Act Two, available at: https://gutenberg.org/files/901/901-h/901-h.htm

But Fanon’s way was to understand the sickness of imperialism as one effective on both sides of the Manichaean binaries it sets up. Rulers are oft sicker than the ruled, for they do not see their dependence on violence, to which they give other names (defence of peace, decency or cultural values, even of high cultural values of beauty and truth) as did France who claimed to be spreading ‘ Liberté, égalité, fraternité (French for ‘liberty, equality, fraternity’’, amongst its Empire and a set of civilized Republican values. I do not know how or if the situation in Gaza and Israel can be saved – my guess is that the brutalisation of its politics will worsen, for we still resist hearing exactly what Fanon says about how violence gets its genesis. After all you can even read Marlowe’s Barabbas, as you can Shylock, as a freedom fighter (like the historical Barabbas who fought against Rome and was freed rather than Jesus by Pilate at what he interpreted as the will of the people) but only if you recognise they have a point about the other side, as is done in a fine version of the Merchant of Venice set in 1936 about which I have blogged (see this link).

Fanon’s anti-colonial theories fed from theories Sartre used to understand antisemitism and the force of those once merely subjected to a ‘gaze’ that negates their very being, in seeing them as entirely nothing of value, gazing back at the antisemite and allows white colonials to feel seen and judged where before they felt themselves invisible to scrutiny. The right of empowered black men to gaze at white men was provided by the poetry of negritude, according to Sartre (for this is the argument in Black Orpheus). Fanon could feel that Sartre often got things deeply wrong, but he never disputed the analogy of antisemite and colonial used by Sartre, in psychological terms at least. Many of his comrades were Algerian Jews. And, of course, things got difficult for these Jews when later leaders of Algeria demanded an entirely Muslim state. If only Fanon had lived, we might know how he faced that conundrum in nation-building that aims for human liberation and disalienation, not an ideological end-point and change of one oppressor for one supposedly representing the majority population.

Vaughan’s admiring review of this biography points out how uncomfortable Fanon would have been with the fate of some nations becoming and remaining dictatorships in Africa. It is clear he did understand how that might happen. She feels that his place would, in the twenty-first century, be in the Black Lives Matter movement, working on the margins of state politics alone. For most of us, this is a problem, for the mechanisms of modern political parties still evoke a ‘we’ that is that of the capitalist state, even if they think we might regulate ourselves in a more adult way than the current government. There really is no space in such a system for Fanon except at the margins, interstices, and cross-fertilisation of elements of peoples.

But you will find a thinker, feeler and actor of great interest in this wonderful biography. Do read it. Find a man who even De Gaulle noticed enough to recognise the power of an alternative to his politics of over-control.

With love

Steven xxxxx

[1] Megan Vaughan (2024:26) ‘Postcolonial pains’ in Literary Review (Issue 526, February 2024), 26f.

[2] Adam Shatz (2024: 369f.) The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon London, Head of Zeus, Bloomsbury Publishing Co.

[3] Frantz Fanon (trans Constance Farrington) [1967:31 – 33 – Penguin ed, first published in French 1961), The Wretched of the Earth Penguin Books (worldwide).

[4] Meghan Vaughan op.cit: 26

[5] Adam Shatz op.cit: 207

[6] Ibid: 202

[7] Ibid: 200

7 thoughts on “This is a blog that reflects on a fine biography, perhaps the best I have ever read of anyone. The book is Adam Shatz (2024) ‘The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon’.”