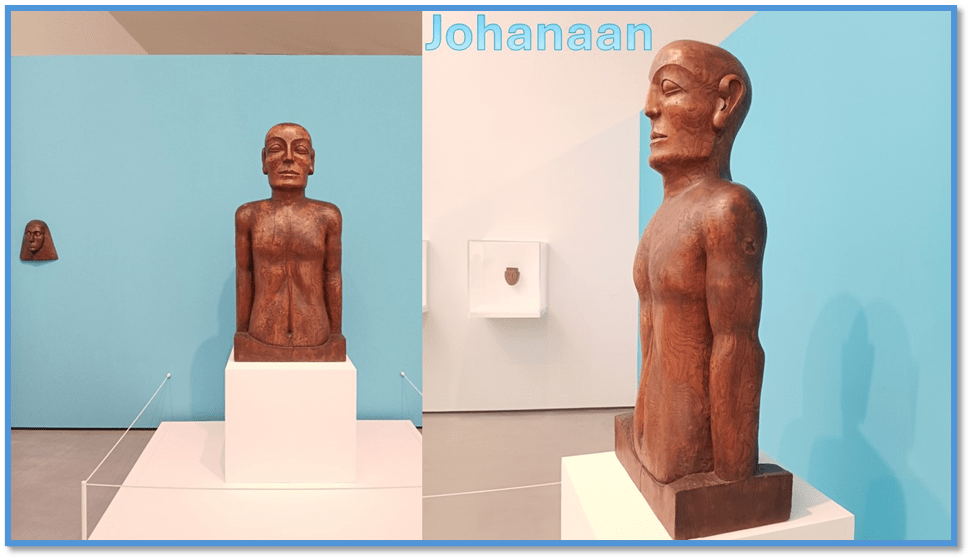

Laura Cumming says of Ronald Moody’s Johanaan of 1936 that it is apparently ‘named after John the Baptist’ but more tellingly and with the sensitivity usual of this critic that ‘this elm torso is curiously androgynous, swelling and undulating and shot through with the glimmering contour lines of the wood’.[1] This is from a series of blogs on a day visit to see the art in exhibitions at the Hepworth in Wakefield and The Yorkshire Sculpture Park at Bretton Hall Country Park. This is number 6 of 6 and the final one.

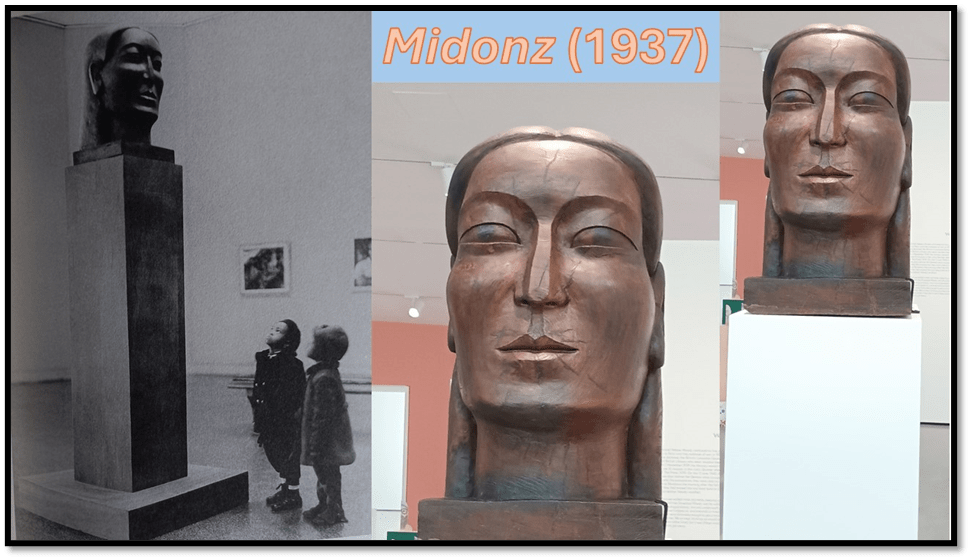

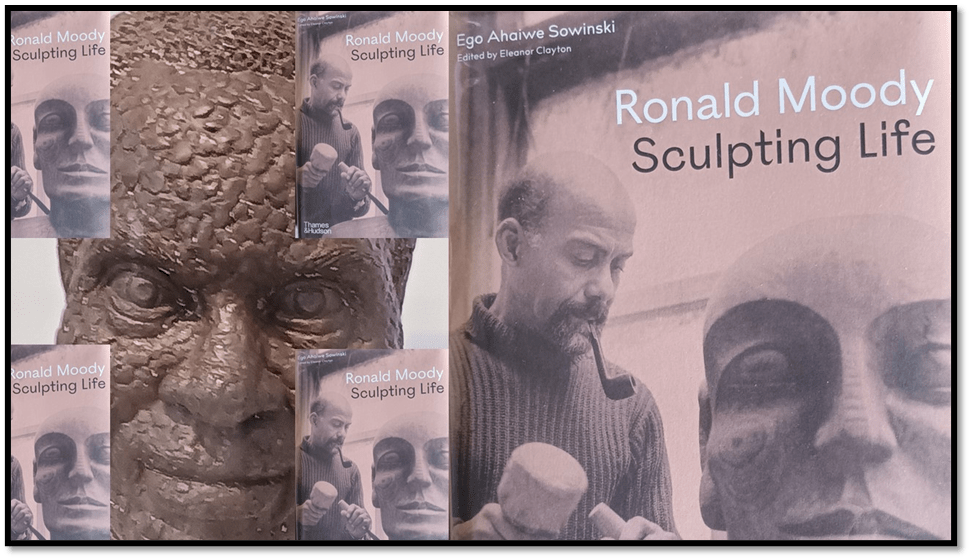

On this day where Catherine and I had viewed so much beauty, we may have been thrown arriving at the Hepworth, and after taking a coffee and croissant at the outside café to shake out the drive from Crook, by starting with Gallery 9 where was Igshaan Adams most wonderful one-room Weerhoud show (see the link for that blog: blog 1). However gorgeous that show though, moving on to the first British retrospective of Ronald Moody’s sculptural achievement ever ought to have been more momentous and I found myself little prepared. After all, here was a contemporary of Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, whose name is little mentioned in that company. This show in itself was some explanation of this. But first for the elephant in the room.

The neglect of Moody was almost certainly neglect related to the race, ethnicity and skin colour of the man, even in days (I remember them so well) when even the national media spoke of ‘colour prejudice’ rather than racism. The generic political term Black had not been invented though people thought it appropriate to talk of Negro culture, as if it described a homogeneous group. This nomenclature was, of course, not confined to use by entitled white people. Roland’s uncle, Harold Moody was the founder of The League of Coloured Peoples, a title that irks now surely, though it allowed Harold to stand equal with Paul Robeson as the other specified great Black hero that Ron Moody venerated with a bust.

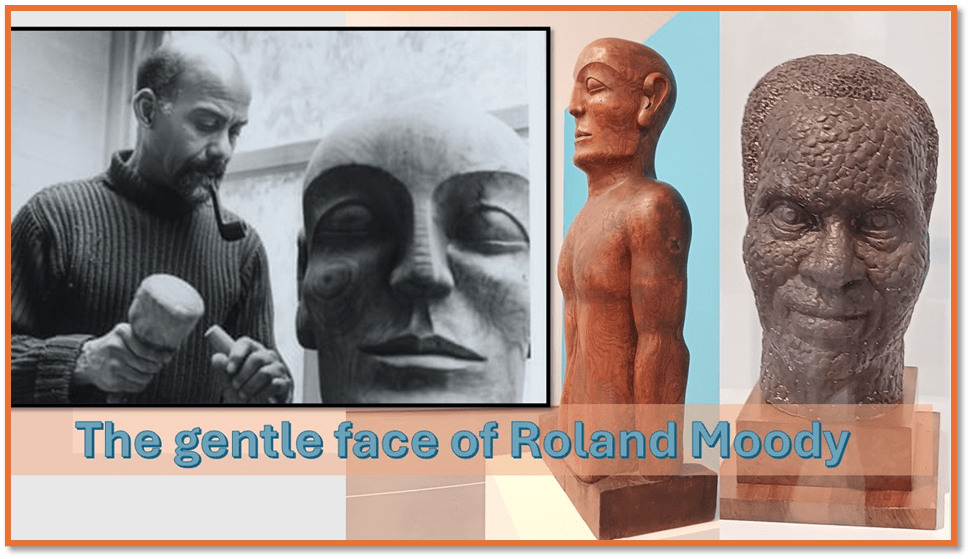

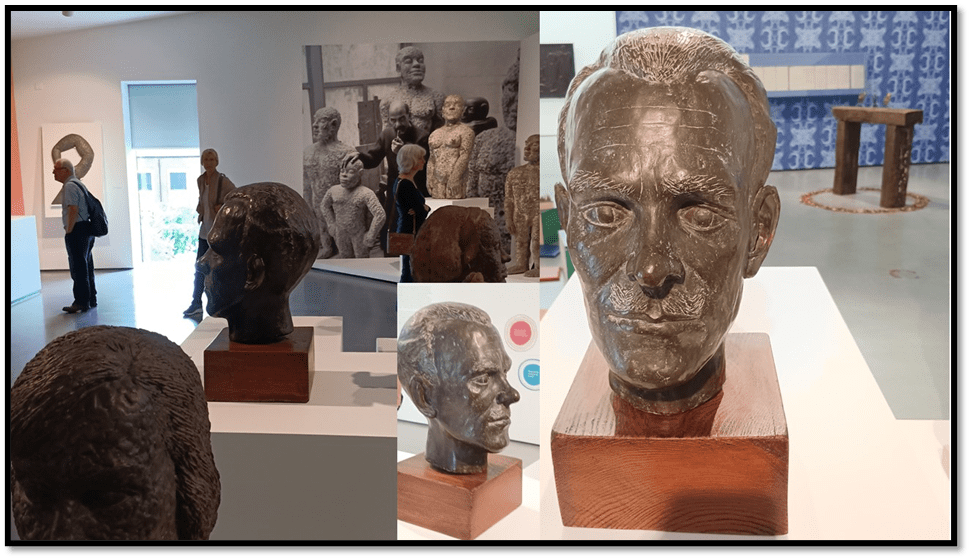

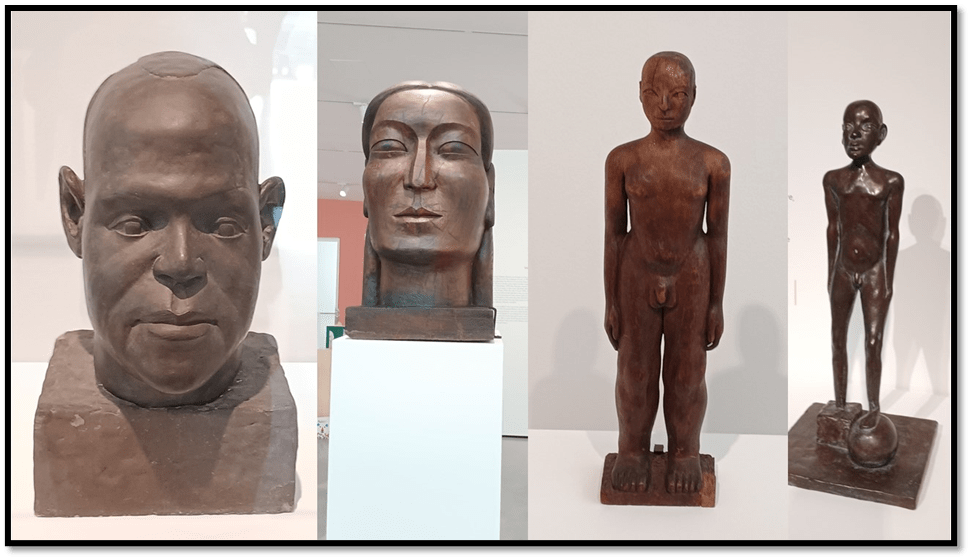

Harold Moody and Paul Robeson. The gritty resin mixture used for Robeson seems appropriate. My photographs although central one photographed from version in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski’s book, ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life’, page 118

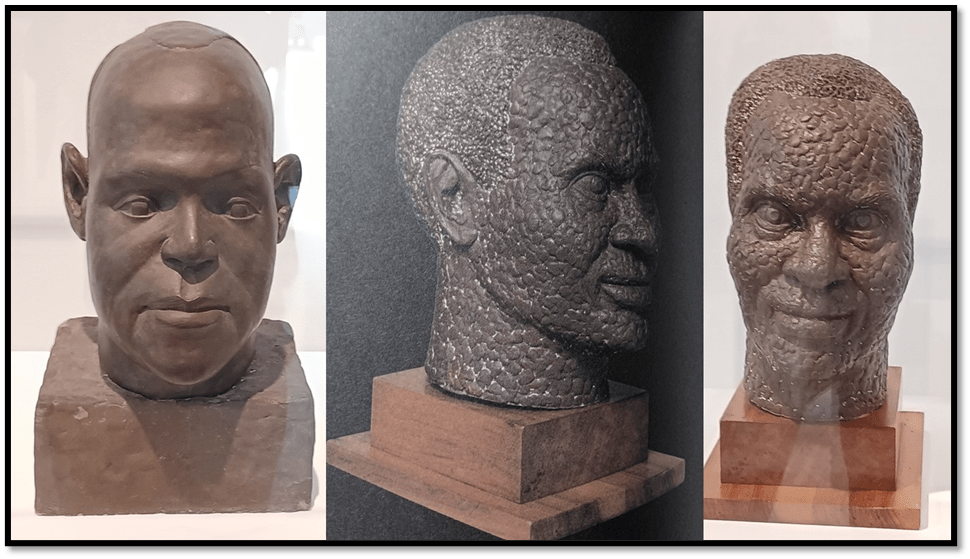

Ronald Moody, in his earlier career, relied on being noticed not as an individual artist, though this he most certainly was, but as a maker of ethnic or even ‘primitive’ art related to the manner in which art was insistently called ‘Negro’ whatever its provenance, as in the catalogue for the Negro Art exhibition of 1935 held in London, which is collected in the exhibition. But we need to be aware that the descriptor ‘Negro’ for that exhibition was chosen in part by The League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) who partly sponsored this exhibition. It had no compunction in deliberately setting modern art by Black people in comparison to the stolen art of West Africa that we know as the Benin bronzes (an now repatriated by the British Museum).

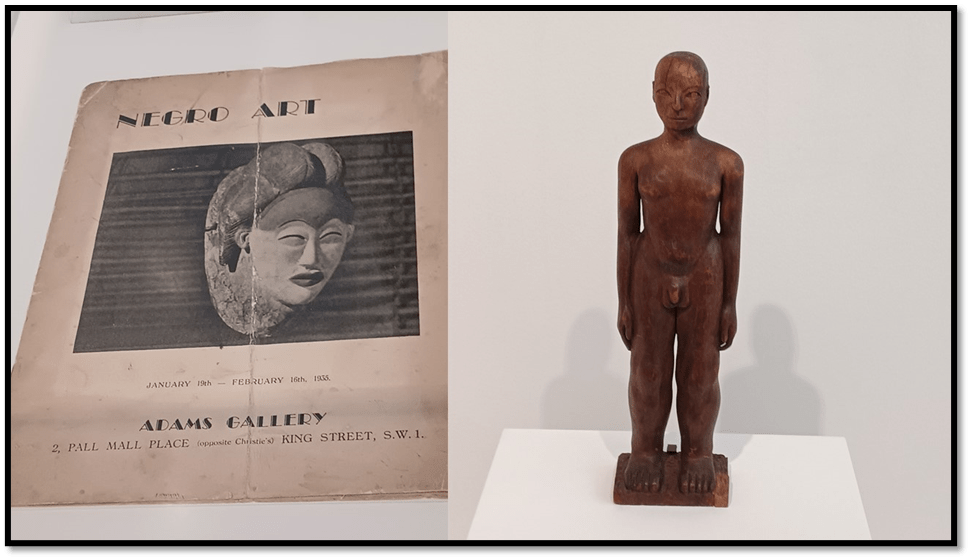

Public displays that introduced or revived Moody’s art though too often used the same manner of associating him with African and ‘Negro’ diaspora art, until the advent of a less oppressive manner of addressing the deracialised and politicised concept of ‘Black Art’ in the 1990s. David A. Bailey in a chapter in the Sowinski book argues that Moody’s art is evidence that suggests he may have championed a more nuanced global multiracial ‘diasporic’ rather than a specific ‘Black visual’ aesthetic. He instances the work Midonz, which was championed in the USA in1939 as an instance of Harlem Renaissance art (in the show Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance in 1997).

One evidence of this, Bailey says, is an iconic photograph taken in the 1939 ‘Contemporary Negro Art’ exhibition which shows two Black infants staring up at the head of Midonz for a role model (see it on the right in the collage below). Bailey thinks the photograph both in its contexts as shown in 1997 and in the original scene of 1939 might well show that the great heads of the period (Johanaan, Midonz and Wohin) were a direct response to the Harlem Renaissance movement and its later revival under Black Lives Matter or black consciousness movements. Whilst admitting that Moody would be sympathetic to that view, Bailey also asks us to see that the work itself ‘actually questions and relates to the question of a diasporic aesthetic’, but one wider that the Black African diaspora:

My photographs of Midonz (right), and the photograph mentioned by David Bailey (cited above) & reproduced in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski’s book, ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life’, page 47, on left.

Midonz brings into question all of that. Is it European?, is it Amerindian? At the same time, when you actually reason why he carved in wood, you notice that when you’ve been close up to the work, the carvings themselves and the marks he makes within them also reference other kinds of diasporic references – in the nature of the making of the work as well as the physiology of it. Midonz is … a head that that references multiple cultures, although the markings that he’s made in the wood suggest that he’s also annotating it and animating it with all these cultural references as well.[2]

Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski however shows that Moody himself was not looking specifically for African roots in examining the context of the making of these heads. Rather they came from the deeply mixed racial past of Caribbean culture, one that also sought analogy with traditions from Eastern and European traditions, and the slightly atypical African example of Egypt. His subjects were archaic and ranged between Far and Middle eastern Semitic sources, as for instance in his first celebrated work Johanaan, as well as those of India and Nepal. First shown under the title Johanaan, L’Évangéliste (his chief admirers were French at this period) the aim was it seems for a truly archaic view of the Biblical story.[3] This multi-racial past is not unlike Moody’s preference for Native American Carib mythologies later in his life.

Let’s contemplate Johanaan for a while for, since seeing it, I have been rather haunted by its beauty and the contradictions within that beauty, Here it is, photographed by me as I saw it:

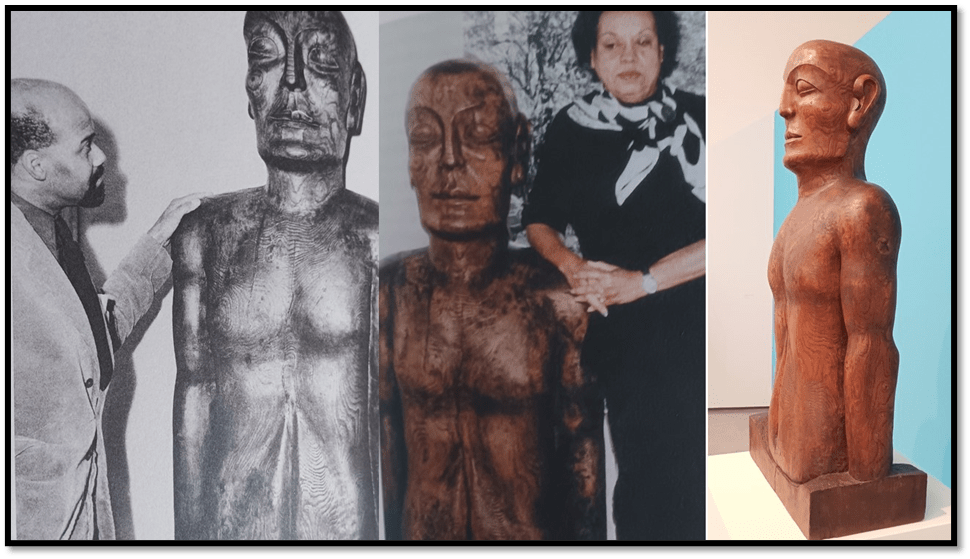

Works change as a result of their history of care or otherwise in curation and Johanaan feels somewhat different in the pictures of his earlier life from the book by Sowinski. In the collage below we see it with Ronald Moody (on the left) and with Cynthia Moody (centre). Even the attitude of these two keepers show the statue in a different light I think.

As with Midonz, the facial features of the statue are stereotypically Amerindian, and perhaps Indo-European: their representation inclined never to strain towards realism. In telling the chronological story of its appearance Sowinski says that shown in Amsterdam in 1938, one review ‘particularly noted “the mighty Johanaan out of which leaps heroism as though it were tangible”’.[4] That people might find a male heroic figure here makes sense in pre-Second-World-War Holland, with an ingrained awareness of the mounting threat of European Fascism, but surely few looking now see a stereotyped male hero. Even the stereotype requires bulk and ‘meat’ (shall we say) in the body than there is the slim torso of Johanaan.

Hence I think I prefer the perception of Laura Cummin as quoted in my title: ‘this elm torso is curiously androgynous, swelling and undulating and shot through with the glimmering contour lines of the wood’.[5] There Is too much of the curvaceous and the ornamentally patterned to be frankly and simply male in the body. The chest bones are highly defined as is the concave groove that opens out the lower body. The torso stops before a penis is required to ‘masculate’ it biologically. Even the head, apart from its size is feminised in parts, such as the brow lines. These features are not those of Byzantine or Western Christian iconography of St. John. Some even doubt whether this Biblical figure was the intended target of Moody’s representative urge.

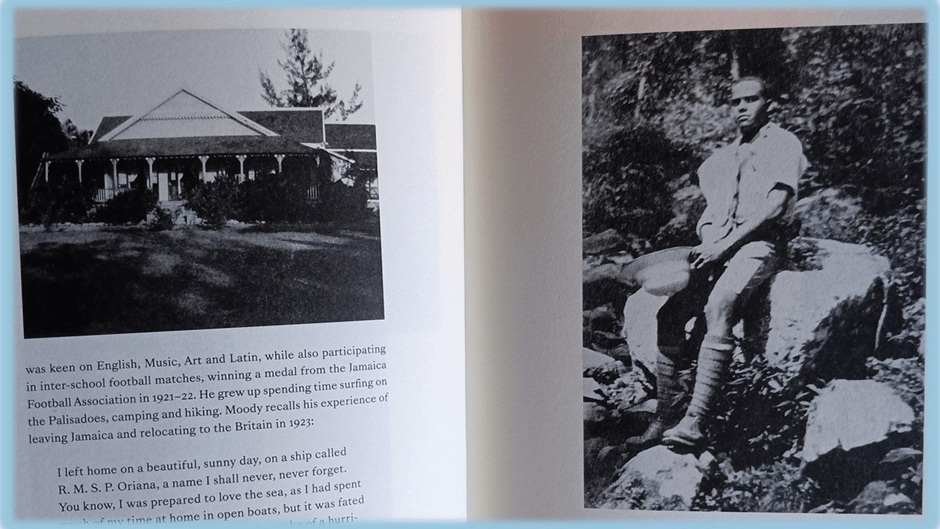

However, there must be a reason for the archaic form of the name of ‘John’ chosen here, which mimics the Hebrew original name (see this link). Moody was a highly educated and relatively entitled middle-class boy living in the rather gracious bungalows of the Blue Mountains in Jamaica as a boy with a traditional English colonial school education: his favourite subjects being English, Music, Art and Latin (see picture from Sowinski below, page 22f.).

He could have known the archaic variation mimicking the same Hebrew in Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, particularly given his residence in Paris as a young artist. Wilde names the Baptist Jokanaan (Iokanaan in the original French text, possibly identifying transliterated Greek versions of the letters).

The Hebrew for of Johanaan

Moreover, Wilde’s Jokanaan is attractively (to the daughter of Herod and Herodias, Salomé) thin. She describes him thus, putting ambivalence into her use of ‘wasted’ in relation to this gorgeous man:

SALOMÉ: How wasted he is! He is like a thin ivory statue. He is like an image of silver. I am sure he is chaste as the moon is. He is like a moonbeam, like a shaft of silver. His flesh must be cool like ivory. I would look closer at him.[6]

This iconic Jokanaan is nearer than the usual Western models and emphasise the lure of art inscribed in bodies. However, I cannot assert her (only guess in reality) the truth of this although I am confident that this attractive hermaphrodite is a possible influence.

Cynthia Moody argues that Midonz, Tacet and Johanaan all have ’similar features’ despite being named under different genders and may have been carved from ‘the same piece of elm’. Friend and novelist Antonia White said, as cited approvingly by Cynthia Moody, that the head of Johanaan was ‘much more projected out of himself’, as a kind of Animus / Anima than he had yet done previously and it is likely that Moody felt the same with the heads to follow, which also blend pre-Columbian Amerindian and Egyptian models seen by Moody. The symbolism of the statues was, like much of the analytic psychoanalyst Jung’s, whom Moody clearly knew and read, alchemical. La Déesse de la Transmutation was another name Moody gave to Midonz and indicated the ability of objects to transition between forms, nature and substances. The transitional that interests me here is that of sex/gender, though it applied too for Moody (and Jung) to race and culture, as well as matter and spirit.[7]

Johanaan, I believe, is an androgyne of this nature too, locked deeply into alchemical, and probably Jungian, theory. And though speculation is futile, it is worth citing that the photographer Val Wilmer was, according to Wikipedia, citing her in 1989, as being noted for (as a writer and photographer mainly in music):

her keen understanding and insightful expression of the disparity between male and female music writers. Entering this world in 1959, she understood that writing about music was “something that men did. There was a penalty to pay for being a woman in a man’s world…[and] for a white woman to be concerned with something that Black people did meant to experience additional pressure.”[8]

Her awareness of the world of intersections of identity in the arts she identifies here must also apply to work on classic photographs of Moody (see below for an example):

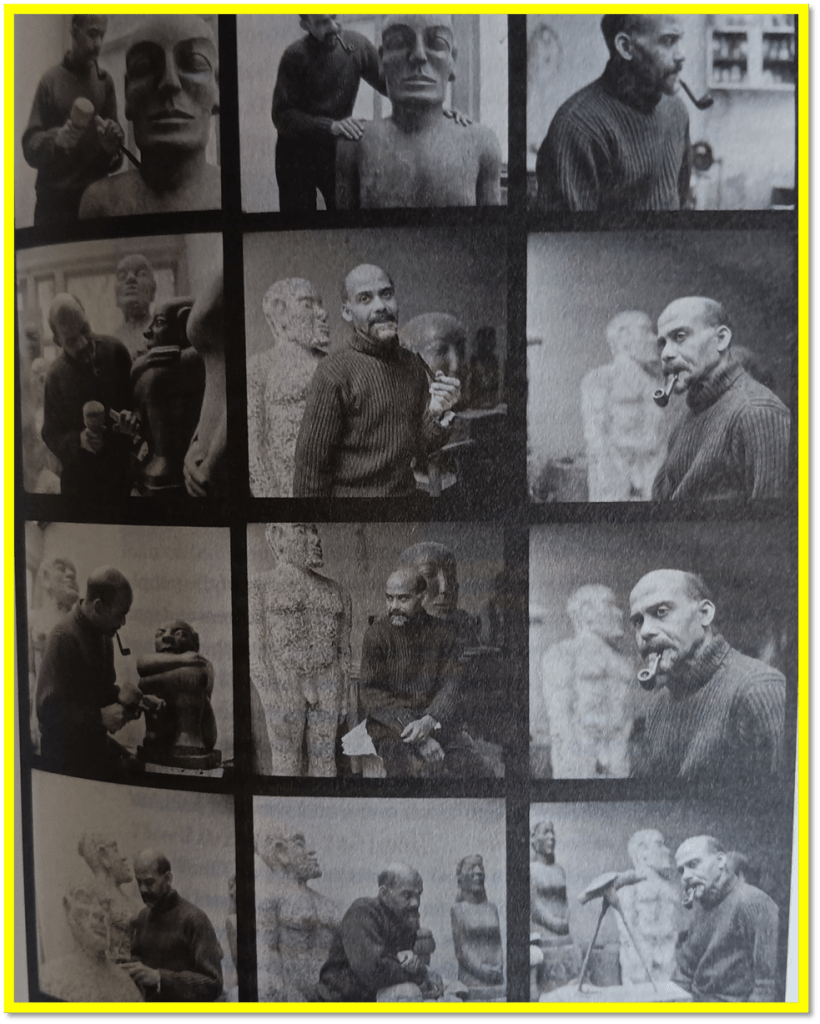

My photograph of reproduction of a Wilmer 1963 ‘contact sheet’ in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski’s book, ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life’, page 143,

Wilmer’s photographs particularly concentrate on the relationships between the artist and his sculpted characters – his almost intense closeness (emotionally and spatially) to them and pride in them, as if they were persons, even when they are faulty. Wilmer says in her interview in the book by Sowinski that Moody was (the omissions not in parentheses are the in speech itself):

… very accommodating to me, very friendly and nice, warm, a gentle person. My abiding feeling about him was that he was very soft physically, a soft person. […] He had the feeling of someone who wasn’t … Although he produced these powerful sculptures, he wasn’t a very virile person himself. That’s the only way I can express it. He was nice to be with, gentle, he was good to me.[9]

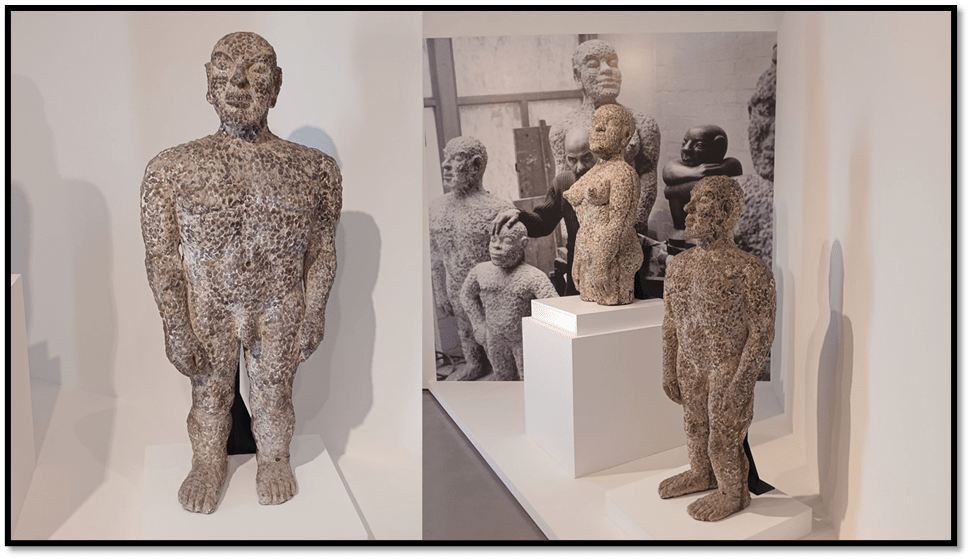

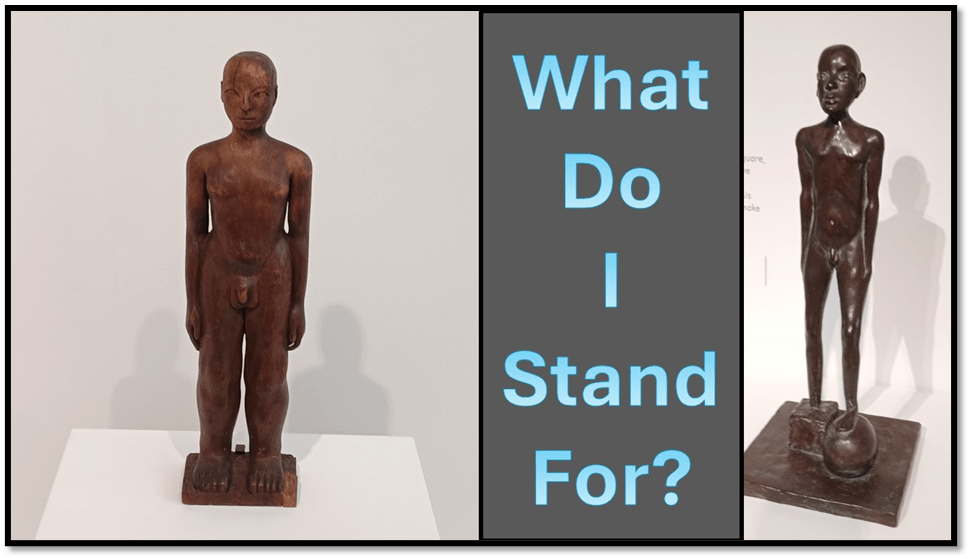

It’s odd to come across such statements but the overall effect here is that Val wanted to associate what was good about Moody with something opposed to the stereotypically manly, or ‘virile’. It felt like being with a woman to be with Moody it seems; it felt protective, as if in the care of what Cynthia called, in describing Midonz, ‘one of the Great Mothers of antiquity’.[10] The determination to recast the heterosexual family is one of the themes I think of those strange works (of which only two remain as statues – although the exhibition had large wall photographs of the others) ‘The Concrete Family’. The remainder are The Mother (1958-9) and The Youth (1958)

Moody’s fondness for the morally faulty piece The Little Man (c.1962) with his hands brashly on his hips and looking out aggressively, comes across in the paternal hand he lies on the diminutive man’s head in the photograph on the gallery wall at the Hepworth (in the collage on the left above). The other (technically faulty) piece was The Man (1958). Made from an experimental amalgam of concrete and fibreglass, reinforced with steel, The Man disintegrated as soon as it was touched’ and the later The Little Man is still lost, fate unknown.[11] Cynthia Moody argues that their aim was to query the ‘high art’ stereotypes of gendered statues – those based on the ‘Greek ideal’ and to query the classical male proportions so important to Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci in their generalised definitions of beauty. But they were also an ‘embodied’ protest at a culture turning into reinforced concrete. I do not think it an accident that only The Mother and a male who is The Youth survive, untainted as yet with toxic masculine rigidity, after all, it was Moody who allowed their making to be more fragile to the touch. Cynthia Moody claims that Moody wanted to address the ambivalence of homosapiens and their wish for a future that threatens aggressively in hard ‘masculine’ materials, but also has a non-destructive ‘female’ creative urge.

She cites Moody in an undated publication saying of the statues that they have some of the ‘constructive values that have sustained humanity through history but that, despite ‘his attempts at denial’ one that energes ‘in an age where the destructive side of Man has become so highly developed, …’. The spiritual search here is, I think, through the development of androgyny, is the only alternative for a generation of toxic men: the unacceptable options being just and only exposing ‘cruelties’ without redressing them, accepting ‘a state of impotence’ or ‘worst of all, cling grimly to dead passing truths’. The Youth lacks the closed body aggression of The Little Man or the pride of The Man in his threatening size and looks upward and forward, his disproportionately large feet firmly planted and his arms in an opening gesture, though still at his sides. His penis is prominent but he is not promoting it like The Little Man.

Hence it may be that David A. Bailey and Laura Cummin are both right to stress the central importance of transcultural ancient figures, particularly those of Egypt rather than those which increasingly stressed the competitive and warlike as the concomitant world of the Greek ideal of the male athlete and warrior in the making. They both note that Moody began to favour Egyptian models following visits to the British Museum in 1928, ‘five years after arriving in England (originally to train as a dentist), and became transfixed, as he recalled, by “the tremendous inner force… the irrepressible movement in stillness” he found there: ‘It is precisely what the finest of his own works possess’.Cumming is also correct of course but some of those figures also have a beautifully individuated personality, she herself noting of his figure’s heads that many are ‘often slightly tilted, with the most delicate inflection of eye and lid to suggest an attitude of joyous thought’. [12] I think that differentiates The Youth from The Little Man, a willingness to somewhat negate his ‘masculinity’.

I stated with hinting at the limitations Moody faced by being considered first and foremost as a Black artist, And more so as a Negro artist. I suggested that Moody sought to cross transnational and transcultural and transgender boundaries in his art precisely to consider the bigger question of what embodied humanity symbolises or does in order to hold meaning. For Moody the issue of Black art must pass an initial portal before it proposes Black Liberation which is the meaning of human life at a deeper level. If art was doing that there is no point in identifying it as Black art and posing a challenge to white entitlement such as that embodied in colonial practices and the diaspora of the marginalised. There is an even deeper sense in which Moody turned to Amerindian cultures for his imagery and symbolisation, for in the Caribbean even the populations descended from slaves are complicit in the death of more ancient Carib cultures, though not of their own enslavement, nor with the intent practised by colonial White races.

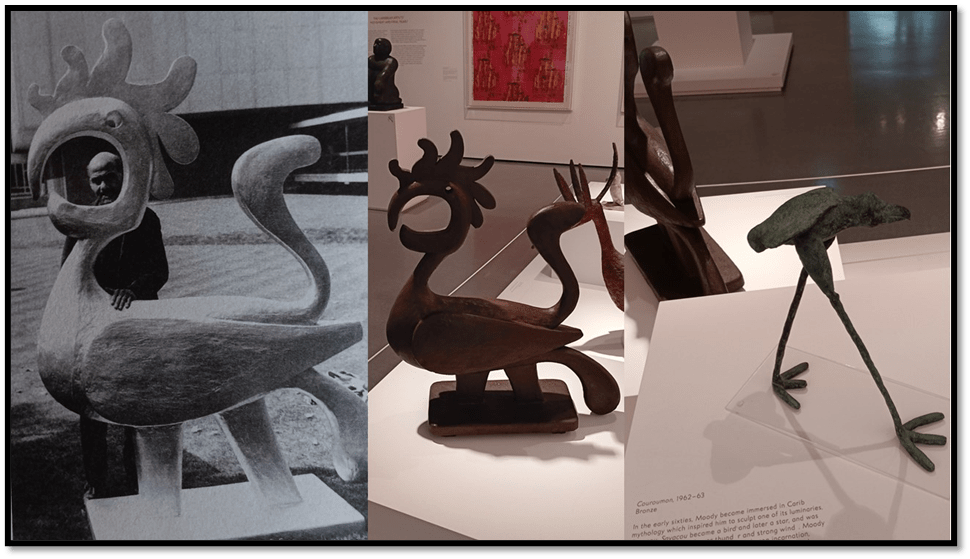

Sowinski suggests that it was to bird symbolism that Moody turned first to query primal animal experience which he, in ways that feel contemporary now, saw in issues of independence, flight (both as aspiration and running away from oppression), freedom and migration. His first attempt at this was the Couromon (on the right of the collage below). It was a heron-like bird on stilt legs, emphasising its nomadic distance walking capacity, but with the intent head and gaze of a quester. He thought of this bird as the heron incarnation of the Carib god Savacou, in charge of the safety of travel of sailors in sea-going canoes. When asked to devise a standing symbolic motif for the University of the West Indies, he chose to invest those meanings in a parrot incarnation pf the God. He said of Savacou, who ruled thunder and winds but became a star-God of Carib cosmology:

He is of West Indian origin, human and divine, and ruler over two very unruly elements. I confined myself to his stay on earth as a bird and have given him some tinge of earthly qualities; a certain arrogance expressed in his form and stance combined with a feeling of power, ….[13]

In his aluminium grandeur, Savacou is 7 foot high. We see Moody staring through the bird’s loud mouth – arrogant on earth but preparing to be a star, his comb representing the starburst of his head. In the centre is the wooden maquette on show at the Hepworth.

Savacou’s story as an incarnation of the imperfect on Earth is no doubt like the story of Christ before his return to become part of a greater divine and material whole cosmos. Savacou also became the name of the Caribbean Artist’s Movement, a voice for the homeland, even its Carib manifestation, and the diaspora of Caribbean people thereafter, including the Windrush generation.

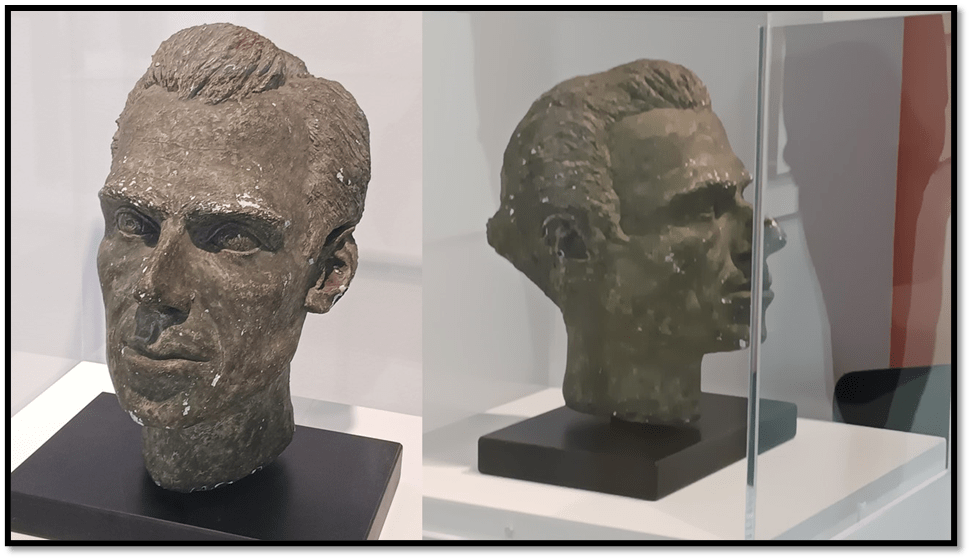

The point is that no incarnation or embodiment of any animal life-form can be singular without belying the story of destruction and simultaneous creation the animal must also symbolise its arrogance and grace. Moody, then, does not address structural racism (although he and his family did do so without doubt in their everyday life – how could they not!) but instead the meaning of the migratory questing animal (profane body and divine spirit) that is capable of using power as destructive force rather than for the good. Hence there were reasons why Moody turned to incarnating the heads of political activist poets like Christopher Logue, whose theme was dispersion of populations and loss of home.

Christopher Logue shortly after the publication of ‘War Music’ based on Homer’s Iliad

There are reasons less easy to explain that he also did a head of Terry Thomas, the ‘comic’ actor whom Moody’s wife, Helene, worked for as a private secretary for 15 years and ensured that his morning newspaper was ironed. The head he produced assures us that that the Thomas they knew was neither bitter old man who died unknown nor the grinning gap-toothed comic persona.

Terry Thomas.

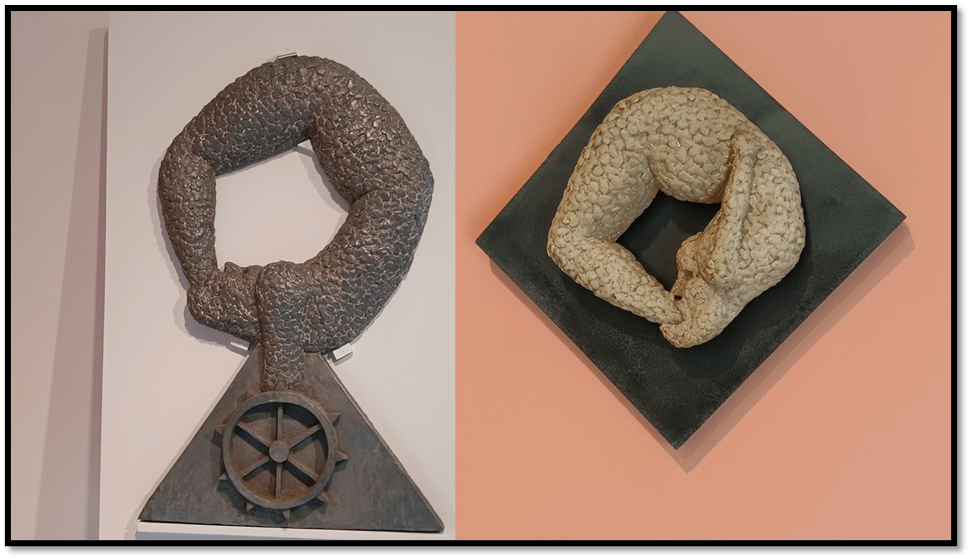

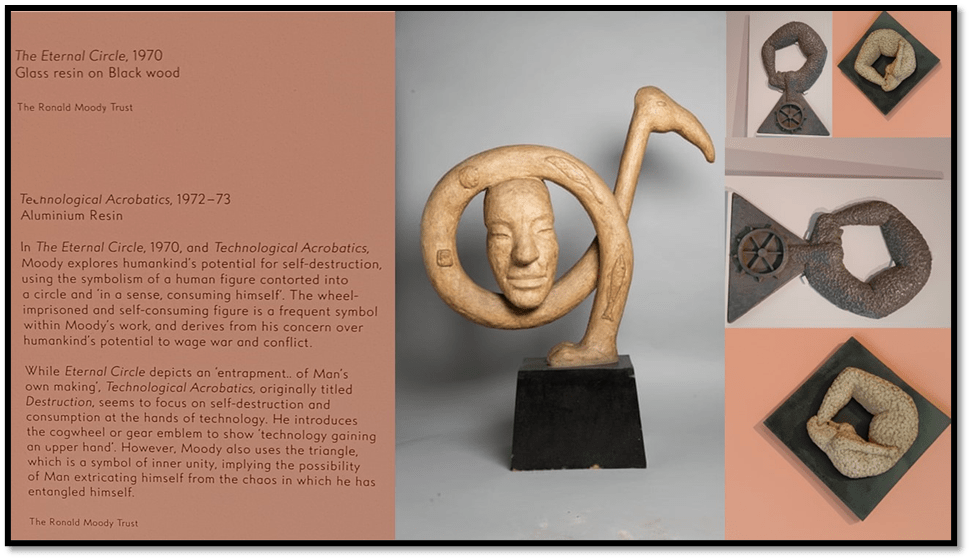

Moody did more abstract Jungian types – an Anima for instance (the Mother Soul) that lived in men and women in Jung’s view, as did the male Animus, but I favour, I think, his ouroboros symbols. The snake with its tail in its mouth was an Egyptian symbol for life in eternity the body ever eating itself so that it is never consumed. For Coleridge and Shelley it became a symbol of the imagination ever recreating what dies. But it was also a medieval alchemical symbol used too by Jung:

Moody turned his snake into a human eating its own feet, attaching in one form the wheel symbol associated with it in alchemy.

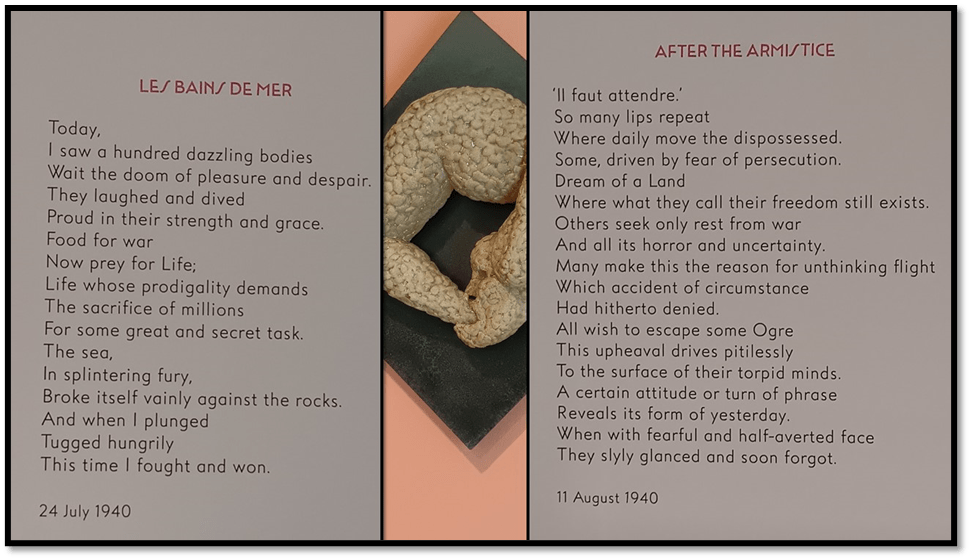

In Moody’s rather good poems (below are photographs of two displayed in the exhibition) the symbol underlies the symbolic structures of Les Bains de Mer – bodies diving and rising, fallen and redeemed , ‘prey’ and ‘sacrifice in War (the war was encroaching on Moody in France at the time) but fighting and rising again. After the Armistice contrastingly takes the events that would overtake any war even at its end (and this was only 1940) – the ‘dispossession’ and migration of populations, the migrant’s pursuit of a new freedom or flight from ‘some Ogre’. There is little hopeful rise in this later poem, for it is still only 1940. Moody’s eye was on the eternal cycle of peace, war, desire for liberty and oppression and slavery throughout history:

The finest ouroboros is one with a beautiful face but a comic cycle encircling it; starting with an animal paw based on the ground, and ending with a dancing and flying human foot. The face in the centre of this ouroboros smiles with the certainty of stillness somewhere. The pretentious name of this lovely sculpture rather detracts from it. It is ‘Man… His Universe’, 1969.

The issue for Moody is easier to understand if we see it as it is discussed by Frantz Fanon (see my blog on this at this link). Fanon, also a Caribbean by birth, may have once affirmed the positive value of positive black imagery in the philosophical position associated often with the Harlem renaissance of ‘negritude’, an early example of Black Pride, but matured into an understanding that skin colour is secondary to the dynamics that create power conflict when the entitled (white races mainly in our world) subject those with less power and resources to dispossession of what they have and to migrations of frightening proportions. For Fanon this dynamic was colonialism. It is likely that Moody would have understood this too as part of the issue of destruction ever eating life up.

So what does human embodiment mean in all the examples below?

This is almost the same question of human beings asking themselves: ‘What do I stand for’? The answer is something to do with achieved stability shown in the big-footed Standing Male Figure of 1951 (only 22.5 inches high) . His achievement of somewhere on which stand is symbolized by his broad feet, like those of The Youth. The concern is that in so many places feet are either blocked in, and forced to stay where they are, or stood on a rolling ball that ‘rolls’ as it must.

The statue Unknown Political Prisoner of 1952 has one foot on each of these dilemmas. Erroll Lloyd says a political statue referencing his interest in broader contemporary issue (he also instances work on Hiroshima) may detract from Moody’s belief that art must be timeless. But the binary is misleading. Time is locked in eternal cyclic or spiral movement in the ouroboros (Shelley saw it thus in his revolutionary poem The Revolt of Islam) and hence to be timeless is to be timely. And the issue of migration from war, hunger, oppression and entrapment is such a cycle that must work its way out to the better. Such cycles apply, Christopher Logue thought, in The Iliad. Perhaps Terry Thomas too fled horror unknown to us.

Fall in love with Ron Moody with me!

The real Savacou huppé

All love

Steve

THUS ENDS MY RECORD OF CATHERINE AND I VISITING WAKEFIELD.

[1] Laura Cumming (2024) ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life; Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud; Bharti Kher: Alchemies – review’ in The Observer (Sun 14 Jul 2024 09.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/jul/14/ronald-moody-sculpting-life-hepworth-wakefield-review-igshaan-adams-weerhoud-bharti-kher-alchemies-yorkshire-sculpture-park

[2] David A. Bailey (2024: 203) ‘Ronald & Cynthia Moody: Evidence of a Black Visual Aesthetic’ in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski (2024) Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life London, Thames & Hudson, 194 – 207.

[3] Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski (2024: 41f.) Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life London, Thames & Hudson

[4] Ibid:41f.

[5] Laura Cumming (2024) ‘Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life; Igshaan Adams: Weerhoud; Bharti Kher: Alchemies – review’ in The Observer (Sun 14 Jul 2024 09.00 BST) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/article/2024/jul/14/ronald-moody-sculpting-life-hepworth-wakefield-review-igshaan-adams-weerhoud-bharti-kher-alchemies-yorkshire-sculpture-park

[6] The Project Gutenberg eBook of Salomé, by Oscar Wilde available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42704/42704-h/42704-h.htm

[7] Cynthia Moody (2024a: 57ff.) ‘Midonz: La Déesse de la Transmutation’ in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski (2024) Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life London, Thames & Hudson, 52 – 61.

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Val_Wilmer

[9] Val Wilmer (2024: 152.) ‘Looking Back’ in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski (2024) Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life London, Thames & Hudson, 142 – 158.

[10] Cynthia Moody 2024a, op.cit: 61

[11] Cynthia Moody (2024b: 140.) ‘The Concrete Family’ in Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski (2024) Ronald Moody: Sculpting Life London, Thames & Hudson, 133 – 140.

[12] Cummins op.cit.

[13]Cited in Sowinski op.cit: 164

With each post you make, I can see your extensive amount of knowledge and the amount of effort you continuously pour into these blogs/essays. You’re one of a kind and I’m so glad to be one of your subscribers.

LikeLiked by 1 person