‘Dreams are like angels / They keep bad at bay, bad at bay / Love is the light / Scaring darkness away, yeah!’[1]. A great film sometimes discovers what is great, truly beautiful and scary simultaneously in queer culture. This blog reflects on All of Us Strangers, a film by Andrew Haigh seen at the Durham Odeon at 4 p.m. Monday 29th January 2024.

ALERT: CONTAINS SPOILERS

Wendy Ide who reviewed this film for The Observer is a sufficiently percipient and sensitive guide to it, I think. This passage describes the film’s opening well. Adam is looking out from his flat (as minimalist and impersonal as she describes it, reminding me of the screen where he unpacks from that ‘ox of family treasures’ amongst other things a cloth ‘fairy’ such was once fashionable for the top of lower bourgeois family Christmas trees (except that this fairy has to me the look of an angel in its iconography). There are liberties taken in the prose, tantamount to the use of a modern day pathetic fallacy, no doubt in phrases describing the external signs of the weather and lighting of the time and season outside, for is it meaningful to see ‘clouds as deep and dark blue as grief itself’ in these human terms.

Scott plays Adam, a screenwriter wrestling with a script drawn from his past. It’s not going well. Our first glimpse is of his face, reflected in the windows of his flat as he gazes listlessly at the London dusk, a wide-open sky massed with clouds as deep and dark blue as grief itself. Adam immerses himself in the music of his childhood – 80s queer pop classics by Pet Shop Boys and Frankie Goes to Hollywood – and picks through a box of family treasures that provide a link to the distant past. But he seems disconnected from the rest of the world – something that his echoing, neatly impersonal flat in a nearly empty Ballardian tower block only serves to emphasise.[2]

I think we are too hard on the use of ‘pathetic fallacy’, where human emotions are attributed to non-human things and agencies in prose, for it is but a device that makes no pretence of attributing such emotions to the things and agencies itself. In effect, it openly admits to being the projection from the internal emotions of a viewer onto the outside world, that sometimes in our interaction with it deepens the inner feeling as if it were reflecting itself into us, in introjection as it were, rather than us reflecting ours onto it. But take a reflexive look at the language we feel force to use – reflection, projection, introjection, inner feelings and interpretation of outward appearance. And as Ide says, the cinematography uses these terms physically. Adam ‘gazes listlessly at the London dusk, a wide-open sky’ but we only know that because the glass of the window acts as both the transparent medium it is purposed to be and a mirror, reflecting back to the looker their open look superimposed or layered on the external reality. In truth then, even visually (given that we also interpret body language and facial expression) we are offered openings to such a ‘fallacy’

And the cinematography (by Jamie Ramsay) can go further. It can shift from the scene described by Ide to an impossible perspective for a human being not using complex viewing platforms that do not exist in the fictional world of the film’s story) of seeing Adam’s naked torso frontally in the same posture and gazing expression, but still unconscious of our gaze on him, from outside the window looking IN on him, so that now we see reflected in the glass medium supposed to be between us, not his face but the scene that gazes upon – that same blue and those same louring clouds. Whether these clouds and lighting express grief, detachment and loneliness or something more turbulent inside Adam, we do not have the freedom to interpret with certainty. Indeed it is better so, because the story of this film is as much about what external appearances, even facial expressions tell us, and what they have the right and necessity to hide and control that lies ‘within’. That, after all, is what narrative is all about – the guesses we make about persons seeing them alone or together in constructed scenes unfolding complexly, and not altogether with certain resolution at the story’s end except in the thinnest of fiction, within the time structure of the narrative.

Later, we see him still looking at and the dark has so advanced that the bizarre illuminations of London’s nightscapes seem to reduce the person whom we only see now, not as a reflection of a face and its expression but merely a dark shadow figure barely human. Later I hope to tie these motifs to modes of Gothic fantasy but seeking a single genre in itself is not the means of understanding a film of this complexity of multiple reference. Nevertheless, film critics like to remind us that they are cognizant of the artistic traditions proper to narrative and cinematography and its iconography. Hence the reference by Ide to Adam living initially in a ‘a nearly empty Ballardian tower block’. The adjective describes Ballard’s famous science-fiction-cum-Gothic fantasy novel High Rise and the film by Ben Wheatley based on it, starring Tom Hiddleston.

Ballard’s surreal science-fiction plays on motifs related to the impersonality and alienation implied by High Rise living en masse, though the whole point of the tower block of flats in rather contemporary architectural style in All of Us Strangers is that they are essentially throughout the film empty flats, apart from the occupancy of Adam, on floor 8 and Harry on floor 6, an equally lonely drifter, Harry, who even finds it difficult to live without even the sound of human occupancy around him. There is even little indication of Harry having an income-bearing working-life outside the flats to fund the expense of these flats, twice referred to as expensive, or of the best alcoholic drinks in the world, as he claims, and full-quality stimulant drugs he takes to dull the pain of loneliness. Some of the latter is Ballardian but not in order to make a point about the nature of modernity, especially in the film, and the fiction for explaining the emptiness of the flats hardly rises to credible realism. I think this is because the flats serve too as a literary device and a fictional architecture of the story, as is implied in the poster in my first collage (here again below) – the building by the way was actually a high-cost set of flats in Stratford East borrowed for the purpose:

In the poster picture are two lonely men divided by emptiness and anomie (they have a floor between them and the curtains of the other flats are closed to view) and they gesture and pose in ways that suggest despondence (Adam) and rebellious frustration at his incarceration (Harry’s had is half-way between a wave and the closed fist of anger). When a fire alarm goes off early in the film only Adam goes to the safe place (alone) outside the building – looking up at Harry’s lit window and the shape figured in it because Harry has assumed the alarm was a ‘fire drill’). Harry sees him too and this mutual gaze through high windows becomes the reason for Harry’s visit to Adam later. That visit is one of the many confrontations that occur at open doorways, where Adam presses Adam to let ‘him in’ but is not let in. On another occasion – but not because of fire – the viewing positions are reversed with Adam seeing Harry on the grass under his high window. They see and wave at each other (Adam half-heartedly). But this is not – I think, even assert – ever intended to rise questions of the realism of the setting or the circumstances of independent living of the queer men in it, any more than does the real childhood home of Andrew Haigh, the director, used as the setting of Adam’s parental home.

For critics the problem is one of maintaining a sense that they are judging not a solution to human questions of the organisation of lives and the problems of disjunction between inner and outer lives endemic to capitalist patriarchy in the status quo, but of the making of sound judgement based on knowing what you are judging. Wendy Ide wobbles with her hint of the ‘Ballardian’, though she is not the only critic to use it, but Ben Bradshaw in The Guardian goes overboard with his show of knowledge of the genres from which the film derives, all of them, it has to be said, plausible to me but definitively a means of normalising the film in context. He says: ‘In its Englishness and politeness, All of Us Strangers reminded me a little of Ian McEwan’s The Child In Time and also Will Self’s The North London Book of the Dead’ (I have added links if you do not know these works yourself). Worse he says of the final scenes, about which many critics were sniffy but we will come to late: ‘Opinions may divide over the film’s final scene, whether it takes this drama too far into another genre’.[3] Do opinions have to ‘divide’ over matter of genre: or do filmgoers actually feel genre is nothing ore than a nod to complexly interwoven narrative and visual traditions in art. Another critic, Christina Newland in the i newspaper, goes as far as to say that the last scenes are ‘contrived and unnecessary’ and hence ‘less believable’.[4] I have already I hope shown though that if the film has a genre it is not one that aims for realism or believability, but rather for what Coleridge called ‘a willing suspension of disbelief’.

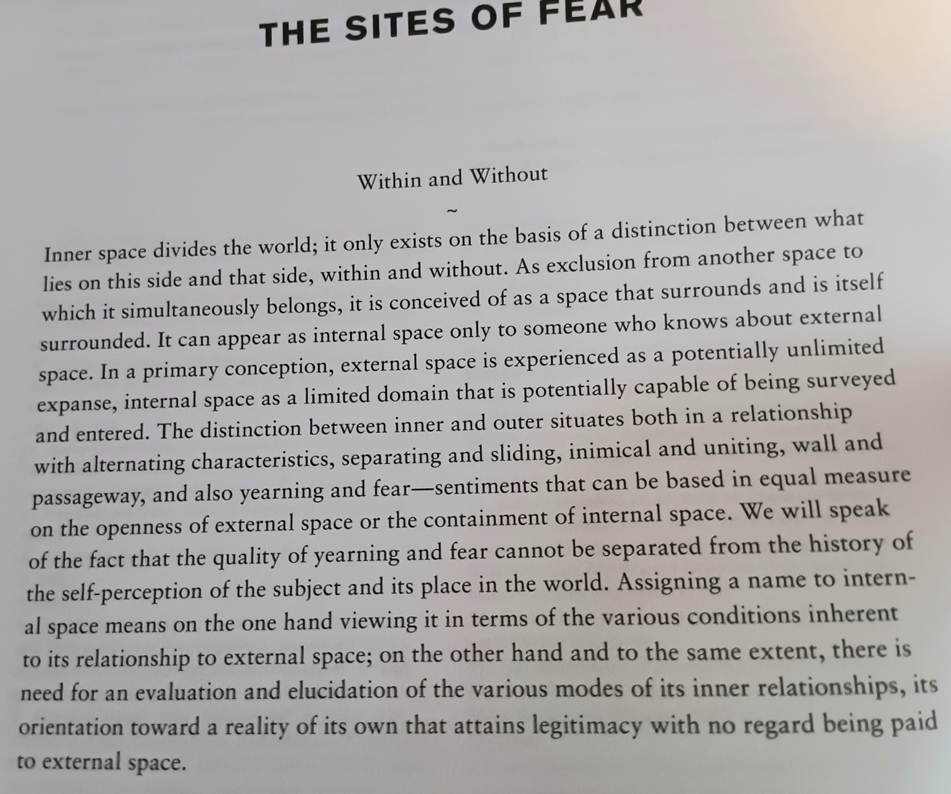

I have indicated already that I think we will find the key to this film in its concern with the architecture of humanity, that which builds thinking, feeling and sensation into a configuration of insides and outsides. This is a difficult idea to convey and is common only in psychodynamic psychology, but it illuminates the art that preceded and followed the work of Freud. I recently found a brilliant statement of it in relation to European art based on ‘Interiors’ from the Nabis and Edvard Munch to Max Beckmann, which I intend to blog upon when considered more fully based on an exhibition in Bonn in 2016. In this catalogue Volker Adolphs defines the co-dependency of the terms ‘within’ and ‘without’ in a passage I will give you in full (and hence in a photographic reproduction) from the beginning of his Die Orte Der Angst (translated as The Sites of Fear):

Volker Adolphs (2016: 32) ‘The Sites of Fear’ in Volker Adolphs (Ed.) Unheimlich: Innenräume von Edvard Munch bis Max Beckmann / The Uncanny Home: interiors from Edvard Munch to Max Beckmann Bonn, Kunstmuseum Bonn & Munich, Hirmer Verlag. 32 -52.

Adolphs, even in translation, is useful here, as is a later section of his essay of the Freudian notion of the Unheimlich and Heimlich (badly translated in English as The Uncanny for English, unlike German, does not see the notion of the homely or familiar [family-ar] as cognates for their opposites n certain usages). But more useful is a section on ‘The Door, The Window, The Mirror’ that are the ubiquitous foci of the paintings and drawings within that exhibition, as with All of Us Strangers. This shows us the if the former two things phenomena are ‘perforated borders between the interior and exterior worlds’, and symbolic of ‘permeable locations in space, thresholds, holes’, the third, a mirror, is a version of them. This is so even if ‘it only simulates an opening; it repulses the gaze, compels an encounter with the self as an Other in the mirror’.[5] Darkness too is examined but we have had enough of Volks to get the idea I think. And, in fact the use of doors. Windows (even reflective windows) and mirrors runs throughout the venues of the film. We have already see above Adam looking out from the large window of his flat on various occasions making a companion of its dark shadows with the mood readable on his face. Adam, with Harry on the last occasion, stands at doors before he is ‘let in’ by his family to a home that is essentially already unheimlich.

On his second visit he confronts his mother (and I am not sure we yet knows she is truly dead, though she looks younger than her son) at a dark, ill-lit door. When Harry first confronts Adam it is when pressed against a door lintel, seeking admission within and holding a half-finished bottle of booze, looking for love, sex or if neither, company in the awful silence of the flats. Adam holds him at a distance that is mimicked by the camera in the still below, though who would not let this lovely cheery lad, with that cheeky gaze, in?

In this film, looking acts of looking and being seen (here at a door) are continually related to issues of access, egress or being shut in, or out, from the place one wants to be or wants to escape, whether outside or inside. Let’s consider windows then now. When the older Adam first passes his dead parents’ abandoned home (as he then believes it to be), he sees himself as a boy looking out from a bay window, the glass of which window reflects back the scene where he stands as if this ghost of the past were a current mirror reflection of him. This scene itself is mirrored by the older Adam on his second visit looking out from another window, dressed in what looks like a boy’s dungarees, whilst his wet clothes are dried, as you can see in the stills I give for comparison below in a collage with thematic informatics:

Of course places are always mediated by portals like doors and windows, thresholds on which invitation to enter or leave either space for the other are negotiated and that co-define as Adolphs says defines the ‘inner space that divides the world’ (‘Der Innenraum teilt die Welt’).[6] I say windows but those portals also include mirrors as Adolphs also shows, which like windows are beaten upon or smashed in as much as they fail to reflect the place one should be in away from an oppressive selfhood, or what appears as such. Windows oft anyway act in the function of mirrors. A fine example is the scene in which Adam and Harry ascend via the lift to their respective flats, where space is both is seen through transparent material but that material (even its flesh components) are continually doubled by the mirrors in the lift.

Perhaps the central or primal scene of , where, Adam having decided that he is visiting the ghost of his parents at the home in which they loved at Croydon takes Harry with him. They find the home dark within and without, eventually trying to see into it from French doors at the rear. What they see in the glass of the French doors at first is just themselves standing outside and denied access, until shadowy figures seem to appear within which Adam, and it seems Harry too, think may be representations of Adam’s Mum and Dad, to all intents and purposes ‘read’ to Adam at least. He stands at the window hammering, asking to be let in, even when Harry flees the scene unable to account with the reflection of Adam’s lost parents realised behind the glass in the light of the absence of his own, whose homophobia had caused him to be cast off.

After Harry is gone, Adam gets access, though the home’s furniture now seems sheeted, as ghosts are sheeted, for a removal from it. He says he wanted them to meet Harry, whom they claim to have seen as Harry saw them through the window but observe that ‘I don’t think it works that way’ to Adam’s continued insistence that they all meet each other, in the flesh, as it were. It is the first mutual acknowledgement that they belong to another world, one in part projected from inside Adam’s own head, for in the scene where the family go out to a fast food restaurant and Adam orders a family meal, the waitress (unseen apart from the arms which serve the food) tells him that that is a ‘lot of food’ (for ONE of course she means).

Moreover, sometimes the reflected scene is more turbulent, reflecting the apparent motion of the scene outside as we see Adam through the window of a moving train on several occasions and distorting his face as an effect of external light falling on the curvature of the train window.

In a scene following Adam’s high on ketamine he willing takes from Harry, he sees himself in a bad trip as a tube train passenger but transformed into the slight and lonely bereaved boy he was. Here, in the dark still below, we see only the scream that accompanies his bad trip, that is returned from deep interior memory so that the face surrounding his open screaming mouth (silenced for we see it only as if from without a window in the tube that has become reflectively opaque). The distorting effect of seeing through one curved tube window a person reflected in and against the opposite curved tube window behind him queers young Adam’s entire face. It is only one example, if an extreme example, of our vision being mediated by such combinations of semi-transparency and DARK reflective opaqueness. And that the face, and the clothing is of the slighter boy he once was receiving news (at the age of 12) of his parent’s fatal car crash emphasises the mirroring and the versions of interiority at play here . The immobile insides in these pictures he inhabits mask or disguise a tremulous suffering interior child revealed in the example below by a scream that is far from still (except in the stillness of another kind of his stiffly frozen and traumatised body) whilst what his outside the window is seen moving fast regardless of his blocked development, as life has done for him.

There is no better means of asserting the Gothicised queerness of the situation of both Adam and Harry than this troubled vision, which doubles and distorts the body, and monsters external appearance by drawing out what is under it or in it to the outside world, whilst also demonstrating how the self externally and internally has the negative and alienating views of a heteronormative and homophobic world imposed on it. I will say more about the Gothic content in terms of queer lives late but we here should just note perhaps that identity queered in this way is oft a badge of Gothic and stories of the doppelgänger, and what Freud called ‘unheimlich’ (or in familiar – where the word family is bedded) but usually translated as the ‘uncanny’ as I have spoken of above using Adolphs.

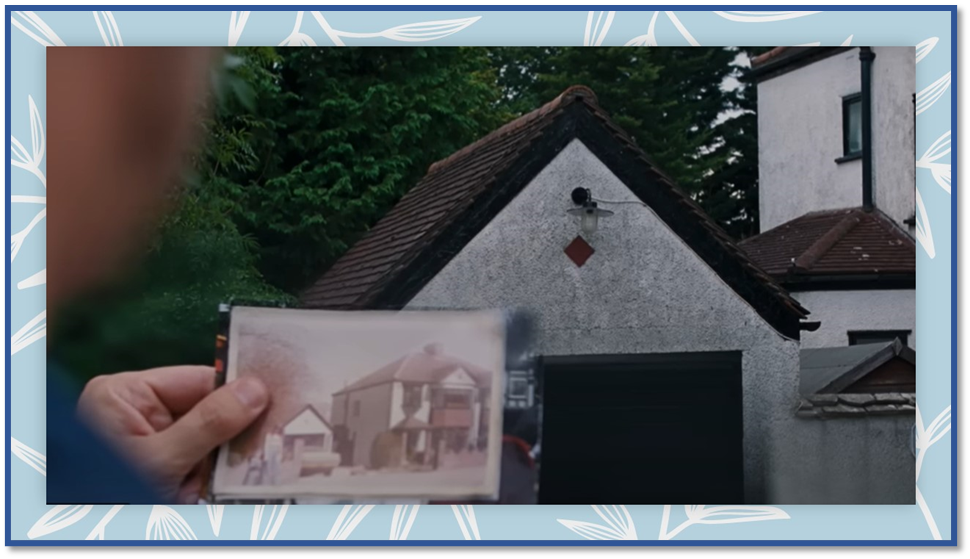

Before we turn to the queer content of all this symbolic play, we need to look at the ‘real story’ being told in the film. Adam is presented as a TV and film scriptwriter, ‘stuck’ in ‘writer’s block’ and troubled. He travels back to Croydon to source momentum for a drama script for a TV or film project that he is basing on his own past life. There, he revisits the suburban house in which his parents lived when they were killed in a car crash (the crash happened when he was 12, and the is at the point of his visit now 42 or so). He has taken with him an old photograph and as he looks at the house as it is now, it seems in all intents and purposes to mirror the house in sees in front of him:

The deliberate doubling of a past image with a present one in the still above is telling and another troubling doubling and mirroring. That is even more the case when we take into account that this house was the actual one the queer film director and screen adaptor of a very freely interpreted novel, Andrew Haigh, was himself brought up in, by parents somewhat like Adam’s (in Sanderstead) , as we shall see them later in a ghostly light. The chances of multiple perspectival vision constantly duplicate in the film in ways I have already suggested, using interplay between seen interior and exterior scenes, with the complexity we have seen described by Adolphs.

Those interior/exterior slippages are sometimes between inner subjective and outer objective worlds, and at other times, just plain old scenes set in exterior land- (or city-) scapes or inside rooms or passageways in a building. It is this duplicity of vision that mirrors represent and hence mirrors are as important as supposedly transparent portals like windows or open doors or lifts, for anyway each can be linked to mirroring . It is a house where both Adam and Andrew grew up knowing themselves to be queer but unrecognised as such by their parents, and who all grew up apart with some sense of alienation that this opacity of ignorance shed on each. However, there are moments in this film that go further in the exploration of queer sexuality than any other film I have seen.

When Adam also visits parkland near his childhood home afterwards perhaps those near Sanderstead pond above), it looks like a place in which queer men, and perhaps even frustrated queer teenagers, might cruise for sex secretly. Over the heath he sees a man of about his own age – slim, attractive and with a moustache, much in the stereotype of the macho gay coming into being in the 1980s. Adam follows him through thickets and catches up with him as they emerge from the heath, where the man asks Adam to go with him. ‘Where’, says Adam. ‘Home’ says the man who turns out to be Adam’s father (played by Jamie Bell quite transcendently and complexly as it should but never named other than as Dad in the script) who introduces Adam to a woman we learn to be his mother (the brilliant Claire Foy) we shall learn with a phrase like ‘Look who I found lurking about the park’

Sexuality is traced back into ‘the family romance’ (as Freud calls, though NOT as Freud describes it) but also in the hidden sexual lives (hidden particularly from family) necessitated for queer teenagers in the 1980s. Soaked to skin on arriving, for the second time, Mum gets him to change his clothes (into almost parodic pyjamas) while discharging the scene of sexual connotation in a way that inevitably also calls it forth in the taboos invoke. It is a scene mirrored by Adam unclothing in the bathroom with Harry who asks if he shouldn’t look and then turns his back, in a way reminiscent of the paths to the shame of seeing the naked body of a loved one that we learn with all its contradictions from parents. Likewise in effect, the scenes where Adam gets into bed with both Mum and Dad and Mum and he recall the past in a loving mutual gaze. But then Dad, who has turned to sleep with his back to Adam previously calls him and Adam turns to find the boyfriend, Harry, saying: ‘What are you doing here?’ The bed becomes marked with its dual (well multiple really) functions and the taboos that separate them psychologically.

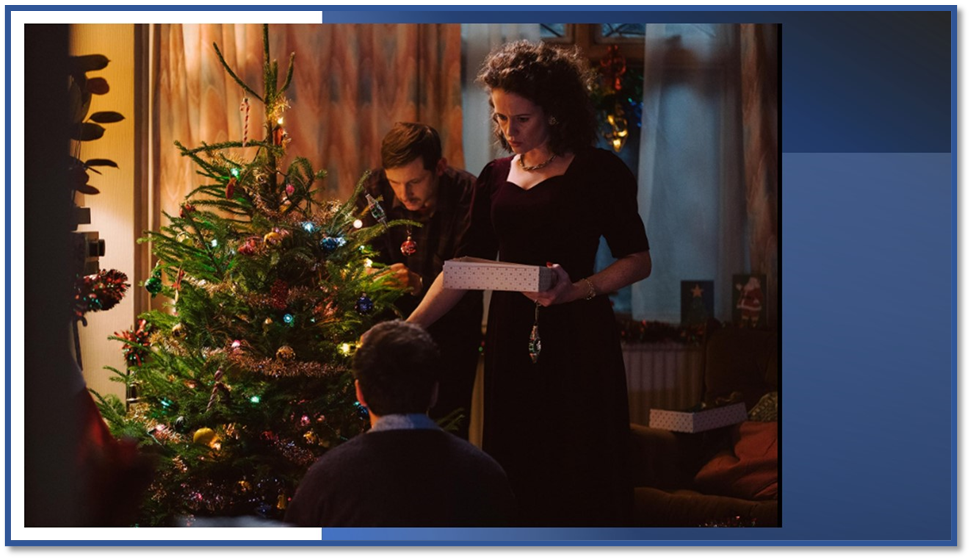

Family is continually romanticised in other ways. Below it is in terms of the scene where the ‘fairy’ that looks so like and angel (or vice-versa) mediates Adam’s relationship to his Dad, a man who in reality was homophobic and could imagine himself as a boy bullying queer boys at his school.

The photograph below is also a still from the film It is one of the few appearances of Carter John Grout as the young Adam, and that moment in which it is underlined that the Adam that we see interacting with Mum and Dad at other times is in fact older than they appear. In truth we feel it in the discomfort with which we register that this man is not addressed as a man but as a boy. It provokes the same ambivalences in us as one thinks it might in him.

However, Adam rather revels in the overt acts of care and patronage bestowed upon him , for much in this film is about the persistence in the adult man of the boy child. It is that persistence that makes Adam’s plea to Harry that he should ‘look after him’ on his first experience of ketamine so beautiful and indicative as a measure of what it means to talk freely in the confidence of returned love. I have to admit I find these issues difficult myself as a queer man for I have experienced this need to be cared for in ways that reveal vulnerabilities precisely because one feels the need that the lover recognise the child in one that usually hidden. Sometimes I, and others, have in real life felt the real disadvantage such exposure can lead to, as love rather than growing, becomes transformed to alienation.

Nevertheless, whilst I say that – this film is also beautiful precisely because it acknowledges that dependence within loving relationships can be troublesome but also beautiful, whether in families or between lovers. When Adam and Mum talk cosily in bed, she confesses howe much she wanted him to grow up so that she could shed the effects of Adam’s clinging nature. It is a beautiful pain to hear this confession of human ambivalence. It is increasingly common now for queer men of my earlier generation and that of the younger generation brought up under Margaret Thatcher and Section 28 and moral panic around Aids to address the negatives as well as the positives of our liberated sexuality. Michael Handrick, on whom I have blogged previously (see the link here if you so wish) is a case in point. Andrew Haigh the director was born in 1973 and is precisely of that second generation I point towards. In an interview in The Guardian with Alex Needham, himself a queer man of roughly the same age, Needham says of the background of this film that it represents the reality

… of a middle-aged gay man who was a young teenager at the end of the 80s, when the Aids crisis unleashed a wave of savage and sweeping homophobia (a British social attitudes survey in 1987 discovered tat 75% of the nation thought that homosexuality was “always” or “mostly” wrong). “I knew I wanted it to be very specific about a certain generation of gay person, which was our generation,” Haigh says when I tell him that I’m also gay, and a year younger than he is. “It wasn’t an easy time to understand that you were gay. Growing up, I felt: ‘If I’m going become a gay person I’m not going to have a future,…’ So I wanted to tell that story.”[7]

This is a moving piece of interview journalism that conclusion Haigh forces us is that both the young and middle-aged men in the film ‘are not lonely because they’re gay, they are lonely because the world has made them feel different’.[8] Even the ending is defended because its radical ambivalence is necessary. It is even I think a greater ambivalence than most critics notice. After all, when Adam finds Harry’s body it is badly decomposed and the man, whose body it was, has just disposed of the bottle of booze we saw him holding at the door in the very early scene. His ghost says to Adam that he couldn’t be alone ‘that’ night’ . But which night? Indeed when I first wrote that last solitary sentence, I was guessing on the basis of an initial naive viewing that the entirety of the relationship (even the sex and clubbing) between Adam and Harry was a projection and/or ghost interaction. Today reading of the plot has ‘come out’ as the key reading, as in the MSN paragraph below. But beware key readings of this unitary kind. Sometimes films are the better for being open to multiple readings.

And here’s the plot twist: Harry died that night, and the entire relationship between him and Adam was all a figment of Adam’s imagination. Adam has been Sixth Sensing throughout the whole film, either as a mental breakdown, disassociating, or a coping mechanism for the deep-seated trauma he still feels from the loss of his parents as a child. The almost maternal way Harry cared for Adam when he had a fever, for example, was wish fulfillment on Adam’s part: he wants a partner to care for him how his mother did, and he projected this role onto a fantasy version of Harry.

https://www.msn.com/en-gb/lifestyle/lifestylegeneral/the-all-of-us-strangers-ending-explained/ar-BB1hqe9j?ocid=msedgntp&pc=HCTS&cvid=55d8899cba1b4714b43ba933c9eb5584&ei=27

It is infinitely better for me to feel that this film is about dealing with the bad and good in the days after gay ‘liberation’ had been thought to become a fact and its mix of wishes and fantasies with political realities of an ambiguous kind in which oppression survived. And, in my reading, the way it deals with it is a highly ambivalent Gothic where binaries like life and death, presence and absence, and inside and outside ‘realities’ are slippery and double each other.

In James Mottram’s feature on the film All of Us Strangers in the i newspaper (which I read after seeing the film) Andrew Scott responds to Mottram’s view that this film is a ‘hymn to the power of love’: “I think it’s about the idea that you have to let love in. You can survive, and you can trap yourself and lock yourself away. But you’ve got to let it in”.[9] And I think, as in the brilliant film by the director Andrew Haigh’s 45 Days, it will get in anyway, eventually bringing with it all the psychosocial complications with which it is networked, however buried in the compacted frozen ice of the past. Universal though its themes, and the take made on them, be (and I hope audiences see that better than Hollywood award-givers), this film is situated in a queering of sex/gender and life experience like no other I have ever seen. And letting love and loved people in happens or fails to happen at doors, windows and mirrors (for one love not let in is that of self). There is a lot of bad and good to process and ‘de-binary’ (if I can coin a verb) in the film with the other problematic binaries.

The ’bad’ is represented by the queer lovers to each other when they sing The Power of Love by Frankie Goes to Hollywood. It too contributes to the streak of the Gothic fantasy in the film that runs alongside the loving and caring between queer men it evokes. 80s songs, especially the Power of Love, matter. The opening of the song are the words Adam and Harry joyfully recite to each other as a poem; ‘I’ll protect you from the hooded claw / Keep the vampires from your door’. It is a song in which men are boys dreaming of a guardian angel (and perhaps one like a fairy – a word branded ion all queer men of that generation) to ‘keep bad at bay’:

Dreams are like angels

They keep bad at bay, bad at bay

Love is the light

Scaring darkness away, yeah![10].

As a queer man reflecting back on the 80s, when I was in my thirties, I seem to remember that at the time any expressed longing to receive a parental type of care – a desire that the inner boy of scarred young men should be safeguarded – had to operate under wraps. It reminded queer men too much of the stereotype of the dependent mummy’s boy, made mentally anxious by a deficit of masculinity. It was not cool then amongst the ‘liberated’ (which we all enacted) to be needy. Perhaps it still is not (it wasn’t for Michael Handrick). And such longings and desires went often unexpressed at the time, even in queer communities. The need to escape sad and ignorant (I am not using the word pejoratively) parents was to the fore for us not their replacement by lovers doing the sad emotional work we missed out on.

We may nevertheless sometimes have inwardly missed the caring of the remnant of child-like need in love. The ‘real thing’ in queer love was a longing for those ‘tongues of fire’ in the song just referenced, the viscerality of liberated bodily sex. Yet that was only part of the agenda of need, amongst men at the least, after an earful for most of us of being told to ‘be a man’ and make that the first and foremost goal in a boy’s life. To be fair this was not the fault of fathers per se. Even in the film Jamie Bell as Dad claims to be one of the kind of boys who would have been bullying his queer son when he was himself a boy but who looks far from that as a ‘SOFT’ and ghostly projection of Adam’s memory and desire. Bell does this cusp behaviour – of macho ideology and genuine love wonderfully.

The ‘hooded claws and ‘vampires’ in The Power of Love are present in the poignant half-jokey references in the film too, as Adam recounts to Harry in more detail his attempt to recontact his Mum (having been banned from the funeral because of his mother’s disfigurement in the car crash where, amongst other viscera, she lost an eye) he returns to the crash scene to find that very eye, noting the ghoulish horror of finding it. Although he in fact only found shattered glass – perhaps with blood on it – he imagines in the story to Harry seeing that lost eye ‘looking up’ at me. Much of the uncanny in this film then, aided by brilliant cinematography of Ramsey, is located in the power of looking, and the ramifications thereof. And this links to the theme that Andrew Scott emphasises of letting love in: indeed, it recalls the modern vampire film Let The Right One In for me. And what we look at or for is that which makes us feel at ‘home’ and hopefully safe. Yet HOME and what ‘home’ is and represents (and even how it can be constituted) remains an open question in this film, particularly for queer men.

That this is so an important advance of honesty in queer film-making where the heteronormative associations of ‘home’ are still an issue, solved, if ever solved at all only in the adoption of a homonormativity that mirrors heteronormativity – coupledom and marriage. Of course, I say this as a queer man who has adopted precisely that answer to the issue in a way that makes me happy but which I still see as problematic in terms of the wider diversities to which queer life ought to be fully open and accepting, even inviting them in.

However, queered situations and scenes that network sexuality and the familial are not I think alone what queers the film, for they have the hallmark of a fantasy that reconciles and soothes, and sort of explain Adam’s bewildered and amazed smile of wonder at many points in them. They recall the past as a family photograph does, or a family Christmas, where Dad reserves the right to his son to top the tree with a ‘fairy’ (in stills I showed earlier in this piece). The richness of that fairy is not lost on the film, it is recalled in the scene where Dad acknowledges he has always known his son was a bit ‘tutti-frutti’. But it is also an ideal that honours family not as a norm but a potential to openness that was often excluded from it in reality. Hence the idealisations of the family scenes, for these are surely NOT ghosts of real parents but idealised projections of the open love Adam needed, and perhaps that we all NEED:

But that Gothic is ambivalent is what we need to remember and that love survived even the 80s as it did the oppressive 50s. Haigh to Needham admits that the film embodies ‘a sense of nostalgia for something we never got to have growing up, because we were so tormented, and that always feels closely related to grief. It dissipates, but it’s always there. It’s like a knot in your stomach’.[11]

And likewise the beautiful and idealised relationship between what may be, and has to be at one point, between man and ghost, parentally abandoned and parentally bereaved. Mottram’s interview with the male stars tend, like many other responses, to dwell on the chemistry of love, sex and companionship in the film, which both stars to some extent attribute to the fact that they are both Irish. Both stars tend to underplay the queer in the film and stress its theme of loneliness and alienation, that they claim to be greater than in Ireland. But in truth both imply that unless we ‘let in’ what we prefer to shut out and conversely let out what we keep in. And I agree with Haigh, cited by Mottram, that what was to got across was not just miming queer bodies in action but ‘a plethora of different things – “intimacy and tenderness and compassion … and sexiness”’. Sexiness is not just sex either of course.

And companionship is very real and so beautifully played, such that the queer scenes, shot in, as Haigh reports it:

the Royal Vauxhall Tavern. ‘I spent many nights there in the ’90s,’ says the director. ‘We saw ourselves as gay indie kids, so I’d go there and to Popstarz and Ghetto behind the Astoria.’ The 50-year-old has mostly given up on clubbing these days, but still knows what feels real and what doesn’t. ‘I wanted to get across what it’s like to be in a club: it’s exciting and you feel together, especially in a queer context, but it can be complicated too.’ The result was two 12-hour days, with proper disco tunes booming out and a sweaty crowd of up-for-it background actors to make it all look real. ‘It’s exhausting and it’s so loud, but it’s the only way to do it,’ says Haigh.[12]

Those scenes in the Vauxhall tavern of all places, are just pure beauty, not quite as I and my husband recall them, though they were fun and ‘complicated too’.

This is a beautiful film and I think Paul Mescal is correct to see it as an acting triumph for both him and Andrew Scott for when people talk of chemistry between these two people it is because the answer is definitely yes to the question he asks: “Does it look like those two people like and love each other?”[13]

AND IT VERY MUCH DOES (even in the stills).

And Wendy Ide makes a good point too about the liberation still in the film:

“They say it’s a very lonely kind of life,” says his mother, lips pursed as she recalibrates her vision of her son’s future after he comes out to her. “They don’t actually say that any more,” snaps Adam, realising as he speaks that loneliness has been the one constant in his existence so far.

See it please for its liberation and its honesty.

All my love

Steven xxxx

[1] For full lyrics see: https://genius.com/Frankie-goes-to-hollywood-the-power-of-love-lyrics

[2] Wendy Ide (2023) ‘All of Us Strangers review – Andrew Haigh’s drama grabs you by the heart and doesn’t let go’ in The Observer online [Sun 28 Jan 2024 08.00 GMT] Available in: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/jan/28/all-of-us-strangers-review-andrew-haigh-andrew-scott-paul-mescal

[3][3][3] Peter Bradshaw (2024: 8) ‘Scott and Mescal excel in yearning ghost story’ in The Guardian (Friday 26th Jan. 2024): 8.

[4] Christina Newland (2024: 35 – inset) ‘An overwhelmingly powerful love story’ in the i newspaper (Friday 26th Jan. 2024): 34f. (inset).

[5] Volker Adolphs (2016: 44f.) ‘The Sites of Fear’ in Volker Adolphs (Ed.) Unheimlich: Innenräume von Edvard Munch bis Max Beckmann / The Uncanny Home: interiors from Edvard Munch to Max Beckmann Bonn, Kunstmuseum Bonn & Munich, Hirmer Verlag. 32 -52.

[6] Adolphs op.cit: the German version is on p. 10.

[7] Alex Needham (2023:6) ‘It’s the hardest thing about growing up queer: you’re not like your parents’ in The Guardian (Friday 29 December 2023) 6f.

[8] Ibid: 7

[9] James Mottram (2024: 34) ‘Chemistry isn’t just about sexuality’ in the i newspaper (Friday 26th Jan. 2024) 33 – 35.

[10] For full lyrics see: https://genius.com/Frankie-goes-to-hollywood-the-power-of-love-lyrics

[11] Cited Needham op.cit: 6

[12] Phil de Semlyen (2024) ‘All of Us Strangers’: Andrew Haigh on the surprising London locations behind his ghostly love story (Monday January 22, 2024) in Time Out online. Available at: https://www.timeout.com/london/film/all-of-us-strangers-andrew-haigh-on-the-locations-behind-his-london-masterpiece#:~:text=Adapting%20Japanese%20novelist%20Taichi%20Yamada,autobiographical%20detail%20to%20the%20story.

[13] Mottram op.cit: 34

3 thoughts on “‘Dreams are like angels / They keep bad at bay, bad at bay / Love is the light / Scaring darkness away, yeah!’ This blog reflects on ‘All of Us Strangers’.”