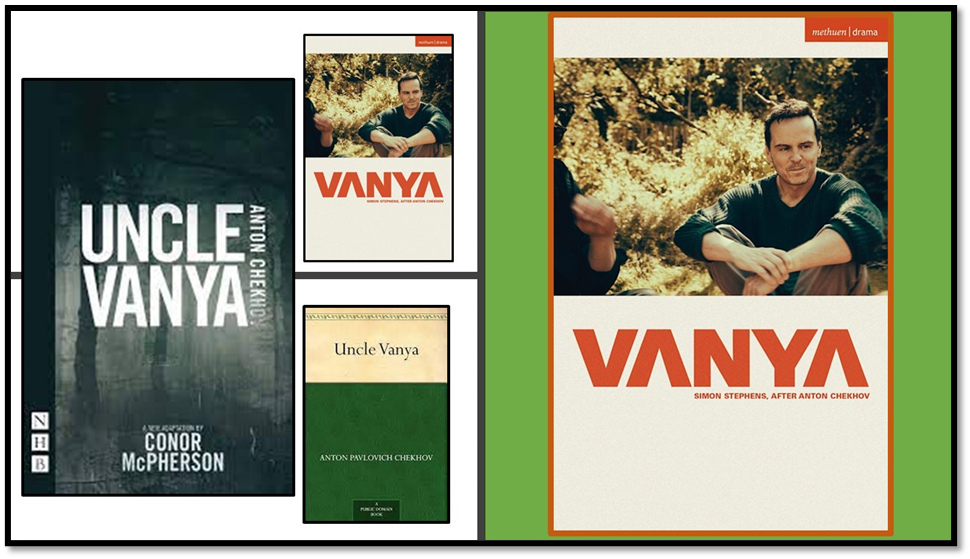

Part 1 of this two-part blog about Andrew Scott’s achievement in enacting all the multiple personae of Vanya. In this part 1, I prepare myself, by examining the audacious text of the Stephens screenplay, to see Andrew Scott perform all the roles of this play, as it was intended one actor would, in the streamed version of Simon Stephens (2023) Vanya, which I will see at the Durham Gala Theatre at 7 p.m. on Thursday 22 February 2024 (the first national streaming). Since the playscript used is itself a relatively free version of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya., in this part I examine the expectations it raises in me in comparison with the freely available closer translation of the play online (available on Amazon – where you pay 49 pence or free online), and a viewing of the less free Conor McPherson version of the play Uncle Vanya, which I read and saw enacted in a multi-star filmed version of the play in an empty theatre during lockdown, with (amongst brilliant others) Toby Jones, Ciarán Hinds and Anna Calder-Marshall.

For Part 2: use this link.

I have been prevaricating about Vanya, because it is a long time since I first acquainted myself with the play, in truth in the early 1960s, whilst in the sixth form and still contemplating the possibility of a theatre career (not an option that goes down well with working-class parents). However, seeing Andrew Scott in All of Us Are Strangers (see my blog at this link) probably committed me to going on, for there is no doubt that Scott is a very fine, if hitherto neglected, actor. It is obvious too that he has mulled over the relationship of his non-appearance in the central role of the ‘good’ character we identify with in popular drama (always The Master never Dr. Who or Moriarty but not Sherlock Holmes) and his sexuality. One way of breaking through the conundrum was the fascinating role of a man alienated not by his sexuality but by a wider intersectional difficulty in ‘belonging’ in All of Us Are Strangers or to play a person who contains multiplie characters within him, regardless of boundaries of sex/gender, age, sexuality, class or social role, in a very great play, as in this new Vanya.

And Uncle Vanya is such a play. When Alan Cummings played all the roles in his version of Macbeth (see my reference to this based on seeing Cummings speak at Edinburgh about his memoir in an earlier blog at this link) which I saw in Glasgow many years ago at the Tramway Theatre, the play was turned into a very obvious exploration of a single character with a multiple and heavily divisive set of selves, that was also an allegory of Scotland during the independence debates of the period. Here was what I said about it in that earlier blog:

Cummings in the 2012 Macbeth then enacts a man whose identity is not as much that of a man but a damaged transmitter, which tries, but fails, to contain (in the sense of keep inside him) the character and story of Macbeth. The play becomes a series of interacting and cross-cutting authentic feelings which have exhausted and torn apart the embodied brain, voice and actions they needed to bring them into being. This man’s posture and look (as of a man from whom life is draining) the National Theatre of Scotland and Cumming can be seen in the amazing publicity shots such as those below.

The troubled aspect of this divided character (the whole was set in a two storey psychiatric hospital in which Cummings seemed incarcerate, and observed through high windows very often by unspeaking psychiatric staff), This framework is not one I expect in the Vanya we are to see, at least, because, from the evidence of the text stage directions at least, each of the 4 Acts is set in a space comparable to those described in the original text and versions even in traditional productions, though it appears that the wider socio-temporal framework of these settings has probably been updated, alongside the updating of the character’ names and social roles. It helps to know that in the Stephens text, the character of the dependent neighbour, Telegin, living with the household of the play is called ‘Liam’ not ‘ĺl’ya ĺl’ch Telegin’, and is unable therefore in this version (in Act I) to make a fuss about being misnamed ‘Ian’ by Helena (in the Stephens version) rather than the case in which he is misnamed ‘Ivan Ivanych’ by Yelena in the McPherson version. For the greater personal knowledge required in naming Russians, even by each other, can always explain errors.

The point is that Telegin and Liam both hate being treated as it were not important to register their true identity. Likewise, in Act IV where Telegin ? Liam admit their fear of being disrespected in a village in which he was once important because he is perceived as being dependent entirely for a place to live and survive on the household managed by Sonia and Vanya.

In each case Telegin / Liam is associated with being a ‘scrounger’ on the social benefits of charity. If we compare a close translation above with other versions , there are interesting differences. Stephen’s curtailed version totally changes the context to get the feelings the character is expressing such that they might be understandable to a modern audience, but then so does Conor McPherson’s version, for the word ‘scrounger’ has so many associations in a divided welfare state. McPherson and the Dover version both still look back to the social system of Tsarist Russia, which Stephens does not do, importing the very modern notion of the ‘food bank’ in a way that addresses issues of personal dependence on the income of others directly.

There are, of course, better examples of this difference in effect, some that may matter more centrally to the themes and values of the play as the adaptation / production sees them and embeds them, but I decided to choose this small example on purpose, whilst still thinking through my expectations of Vanya in a preparatory manner. Conor McPherson wants us to see both the modern category ‘scrounger’, and a man trying to preserve his self-esteem in humiliating circumstances, having lost his estate, his wife and the chance of his own family and having found no substitute in income or associations with others. For this man, forgetting his wallet is an added character trait ambivalent in determining his actual insight into his condition, and the source of his observed dependency. However, in some ways McPherson’s village shopkeeper is more mannerly and speaks apparently privately. Hence their motivation is more understandable and forgivable socially than with those people in the other versions. Those latter two examples seem to present village shopkeepers who merely want to belittle a man, already known to be powerless and belittled socially and in his own eyes, rather than make a point about not giving credit on sales at their shop. The relevance of all this is in fact rather central to a play which clearly looks at the sources of self-esteem and endurance in men and women.

Sometimes this may seem specific to the situation of people in Tsarist Russia but not always. It is certainly true that Chekhov was often berated in his own time, and in a context of social transition, of NOT being specific enough about social ills, as say Ibsen very definitely was. His character may survive on less than they think they are due in either respect, status or income but they survive well enough to be bored by inaction or tired by pointless repetitive routines, such as the accounts Sonia and Vanya keep to keep the household afloat. This applies to Sonia, Vanya (Ivan in Stephens), Yelena (Helena), Mariya (Elizabeth) and Serebryakov (Alexander) as well as Telegin (Liam). The old retainer servant Nana (Maureen or ‘Reeny’ of uncertain status in Stevens) is of course continually busy and expected to stay so – although often no more so than characters who do want wish to be reduced to ‘service’.

Much of the ‘action’ of this play is about how not only to fill the time available in the play’s duration, and in their continuing lives, but to convince yourself that you are filling it meaningfully and have a function. Serebryakov turns time and its schedules on their head, his playing at writing important articles is a ‘race against the clock’.[1] Mortality and sickness haunt him in all versions. It is, par excellence, the play of the imposter syndrome, wherein every character doubts they are worthy of taking the role they do, or pretend to do (or feel they could do – for Uncle Vanya thinks he ‘could have been another Schopenhauer, another Dostoevsky’.[2] In the Stephens version Ivan could have been ‘a Bresson! I could have been an Ozu, for the context of the family role in the humanities is for Stephens in the world of filmmaking and criticism, not art and philosophy, and its critique in the original play. For the women these roles in all versions are more to do with being married to people with the status the men think they have, act as they have or pretend they could have had. Hence Astrov, a professional – a doctor – blames Yelena for not being occupied, though occupation would be served by serving his passion for the environment rather than Serebryakov’s outdated academic output, Vanya’s messing about in lots of things or even than a role of her own choosing: “Respect you? How can I respect you? You have no aim in life. You do absolutely nothing to occupy your attention – …”.[3] At another place (Act 2) of Stephens’ version he says ‘all she does is eat, sleep, go for little walks and swan about. Nothing more. … She’s idle. Idle people can never be truly beautiful’.[4]

In the play the chief imposter (Vanya says ‘You are a fraud’ quite directly and Ivan says to Alexander that he ‘wouldn’t understand art if it shat in your face’) is Serebryakov / Alexander. And I think Andrew Scott is good at playing people who pretend their life has meaning, though all actors who are truly actors should be thus capable. But the thing is that this phenomenon of human endeavour can easily be enacted in one person against all variants, even in those differences in it, for they are socially constructed between women and men, the old and not so old, the socially powerful and powerless. And indeed I suspect the idea of an ‘imposter syndrome’ may truly live in all its cunning variations of similarity and difference, empowered or disempowered as well as in relative forms of authenticity, where we sense people use their sense of the meaningless of what they do to make it matter in at least small ways.

The ultimate form of imposter syndrome is the need to survive yourself – to have identity beyond death. The play ends with Sonia imagining that her attitude to the loving service to others will characterise her whole family and class. It is the play’s deepest illusion and seers the soul that ought to want the ‘caress’ Sonia sees in it, Men are more egotistical, well apart from Yelena, who is just mixed up about not either being or having that which would satisfy her, though she does not know what that is. Ostrov (Michael in Stephens) twice, at the plays beginning and end wonders how people will see us, but I think he means him, in 200 years’ time. But he alone has an ecological vision of that time-space, related to the use values of land and time – in truth he is a Marxist manqué (which is sometimes claimed of Charles Dickens). His vision of socio-economic change is psycho=geographical in its power (truly exciting in the McPherson example) who deal with the matter of the time-space comparison with maps and charts showing forested areas friendly to avian wildlife (‘a ‘”power” of birds’ as he calls it in Stephens alone) brilliantly. For how Scott does this I cannot wait:

Within fifteen years. Less. The world changes. Culture changes. Old ways of life give way to new. It’s what happens. I understand that. I do. And these forests will be replaced by roads. There’ll be industry. Factories. Schools and people will be healthier and better off and better educated but that’s not true. That’s not happening. It’s not. Everything’s been destroyed, nothing has been created.[5]

But that all being said, the test of this production is how the voices in it are differentiated and have convincing dialogue in one person, from whose mouth they proceed. The similarities and differences abound but how will they be conveyed and must it be at the expense of making it about both dissociative and multiple personality syndromes at the same time – categories more proper to Gothic than good psychology. What strikes me as I read the play and produce all the voices in my own head, as all readers of drama do, is how many of the characters reproduce my attitude to real people that I think I really know or knew. I feel I have more than ‘a smack’ (as Coleridge said of Hamlet, the character, in him) of both Vanya and Alexander.

The messy productiveness of Vanya that don’t add much to life really except a sense that I could have put more into it had my circumstances been different, Alexander’s narcissistic sense of having something to say that he knows no-one listens to, I can identify with all that. And Astrov’s truncated idealism – yes I have a ‘smack’ of that in my political imagination and plans. Vanya’s mother knows this of Vanya. He is a man who had the wherewithal, unlike her (a woman in a patriarchal society) to be ‘a human being with agency and respect, and what have you done with it? Sweet damn all!’[6]

But the puzzles are the female characters – who imagine their meaning in some fulfilling love (perhaps in lieu of action in the world they feel disallowed). I have to say I thought I recognised Yelena so much in a lover who abandoned me and my husband – someone who wants to act well and who therefore acts atrociously, someone who acts on impulses that they mistake for strong beliefs and feelings. Someone always looking to be at the centre of dramas they self-create. The scenario in Act IV where Astrov confronts Yelena in the McPherson version is powerful. So powerful in production but even in reading. Yelena keeps insisting she must leave but wants not to feel the consequences of doing so, or to push them back onto other people, even her victims:

It’s already been decided. That’s why I can look at you so fearlessly. But I will ask you one thing. Please think better of me than you do. I’m more than you take me for and I would like you to respect me.[7]

In fact Stephens get this even more infuriatingly correct, ending it with the request rather enlarged and asking complicity of the victim of her decisions: ‘I want you to respect who I am and what I want and the decisions I’ve made’).[8]

And, as far as I believed, Astrov reacts in the event to this how I wish I had to the situations when people ask you to validate their less than respectful behaviour to you with respect to them:

You know, it’s so strange. I look at you and I see a well-intentioned, warm-hearted person, yet everywhere you go you wreak havoc.[9]

Stephens does not have an equivalent of that speech, It’s a pity. Don’t get me wrong in this little part of my blog. This is not an attempt to capture a person’s being in my past life as they truly are but to illustrate that characters in the very best dramatic work can encapsulate those moments where we see each other in terms of our competing interests in being as e must be. And, for this reason, I think a one-person, Vanya of all the roles could truly work. It is a tall order for one person to do all this. For look not only at the list of dramatis personae but the vast talent allotted to each role and heir capacity for ensemble teamwork. One obvious thing we may miss is the pattern of familial and other relationships in the play, difficult enough with most Chekhov plays. Note how this graphic attempts to help baffled readers / audiences – though for a production I have not seen.

But the craft of acting individual roles in ensemble can be a wonderful thing. It creates its own meanings in relation to the dynamics of social arrangements between individuals who differ without being other than each other.

Susannah Clapp pointed out at the time of the making of the McPherson DVD and TV screening the wonders of ensemble work and how it became a counterpoint to both the play’s themes and the circumstances of lockdown Britain under Covid-19. Here is some of what she says:

Chekhov’s 1899 play is prefaced by shots of the cast arriving – dungarees and masks – at the Harold Pinter theatre for the first time since March: shaking out umbrellas, walking into an empty auditorium. As the action begins, something extraordinary happens. We are transplanted in time and place – there is nothing 21st-century British about Rae Smith’s lofty, crumbling design, the sodden glimmer of Bruno Poet’s lighting or old Nana with her long dark dress and bun, patiently waiting on everyone. Yet the stage is charged with the climate of Covid-19. That combination of sluggishness and highly tuned irritability, the feeling of time mysteriously slipping by, maliciously cheating people of their lives, is everywhere: in Toby Jones’s crosspatch, crumpled Vanya and Rosalind Eleazar’s Yelena, so heavy with disappointment she is scarcely able to move. The lassitude of Chekhov’s characters is sometimes spoken of as if it were a mental elegance: here, it is plainly toxic; everyone might be hung over after a too-long afternoon nap.[10]

Compare for instance this publicity still which shows each actor in role but not connected dynamically, with the one that follows that shows their relations realised, as much as a still can, in the spatial relations of the stage, settings and each other and including posture, pose, expression and gesture.

An ensemble can form other groupings where everything matters and is conveyed even in statuesque still and silence, See Serebryakov’s gaze at Vanya (not seen by us) and the complex reactions to all that in dyads as well as individual responses behind him. The brilliance of the actor playing Sonia (Aimee Lou Wood) shines through here, even in the presence of Anna Calder-Marshall (as Nana).

Below the brilliant portrayals by Rosalind Eleazar and Toby Jones, tells us a lot about the sexual machinery, often manipulated, in the play, but here in the relationship where the consequences will never be devastating but are illustrative of this relationships that are: Serebryakov’s coercive control of Yelena, and Yelena hopeless impostership of love with Astrov.

So next Thursday will be a fascinating night in the Gala Theatre. In the anonymous Dover edition ‘Introduction’, it says that Chekhov was ill at the time of many of his productions and was ill when they were produced first, by the great theatre and acting theorist, Stanislavsky. In particular this, that Chekhov: ‘who described his plays as comedies, not tragedies, never thought that the director, Stanislavsky, achieved the light touch Chekhov craved in their presentation’.[11] Here is a case in point, though the McPherson had lightness (especially in Toby Jones’ brilliance) the overall feel was not of the great cycles of renewal of comedy. I think Scott might provide lightness certainly but I think achieving comedy, as we understand it at the least, is not desirable. However, one takes Chekhov’s point in the one famous still from the original production, where Vanya shoots his broth-in-law in Act III (and issues of course).

But Chekhov was well known as a wit. So is Scott. I think lightness a certainty.

I relish the event coming up, even though the day before I will have day-tripped to London for Art shows (the wondrous Auerbach charcoals in especial). In Part 2 I will report back on the film itself and Andrew Scott’s performance.

With love

Steve.

[1] McPherson Page 31

[2] Ibid Page 67

[3] Ibid Page 78

[4] Stephens p. 20

[5] Ibid: 27

[6] McPherson: 67

[7] Ibid: 77

[8] Stephens: 39

[9] McPherson: 78

[10] Susannah Clapp (2020) ‘Uncle Vanya review – coronavirus gives Chekhov a shot in the arm’ in The Observer [Sun 18 Oct 2020 10.30 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2020/oct/18/uncle-vanya-review-coronavirus-gives-chekhov-a-shot-in-the-arm

[11] Loc 72, Kindle version of Dover edition.

5 thoughts on “Part 1 of a two-part blog which aims to talk about Andrew Scott’s achievement in enacting all the multiple personae of ‘Vanya’, as aspects of the solitary and solipsistic self, perhaps. (Part 1 is about preparing myself for the novelties of the Simon Stephens’ text).”