What skills or lessons have you learned recently?

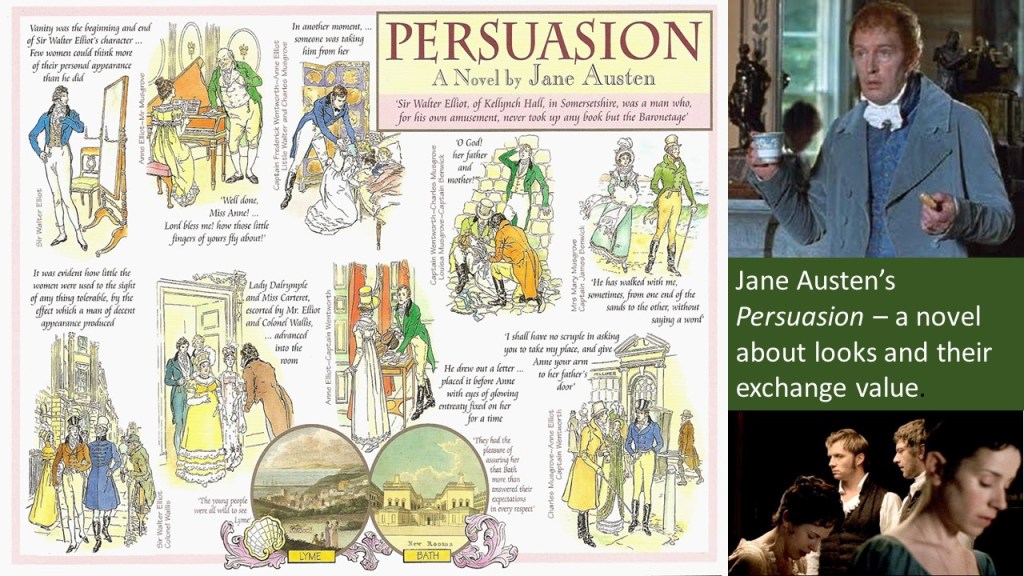

When I taught literature at the Roehampton Institute, I once composed a lecture on Jane Austen’s Persuasion, my favourite of her novels, about the agency of ‘looks’ in that story. It matters because it is a novel of total concern with both how you look (the vanity of your appearance) and the exchange of gaze in which people assess each other for various motives. In those days, I felt I was, with my students, discovering a theme in a great writer, and just reveled in that novelist’s brilliance and genius. That Jane Austen was just wise in a very primal knowledge of the mechanisms of interaction escaped me and did for some time. Men value intelligence as if it were an abstract quality, which it is not, so much at least as men think, I think.

Very recently, about a month ago it started, I bought Jonathan Cott’s book about the life and work of Maurice Sendak remaindered at Durham University bookshop. I knew and admired Where The Wild Things Are, having seen it on a friend’s bookshelves, those reserved for her children, and I was intrigued by Sendak’s reputation as both a curmudgeon (known popularly as Morose Sendak, and a closeted queer man).

The book sent me on a journey, not least in discovering the book Cott considers the masterwork, Outside Over There. I started a blog on the artist, after reading another biography, of his life from 1980, by his fellow artist and dear friend, Tony Kushner. These two great queer Jewish men had a lot to teach me about the nature of knowledge pursued for its own sake and without the interests set by adult career or masculine status-seeking. For both respected, deeply, the knowledge essential to children that most of us otherwise fetishise in a manner not unlike Wordsworth did, as a tool for knowing something abstract quality like ‘Nature’ or a primal state of supposed innocence.

But we learn about looks and reasons for monitoring them early in our life and Sendak took a special interest in this, attributing his depressive states to his childhood. He learned more from a lifetime of therapy and from his lifelong partner, who was a well-known psychiatrist. One way we learn about looks in relation to our appearance is via the mechanisms that Freud named ‘primary narcissism’, mechanisms essential to the formation of an integrated notion of the ‘self’, an ego, that will go on to affirm, despite the evidence of dreams and the threat of either neurosis or psychosis, that this psychological construction is all there is to know about the self. But there are other mechanisms I think I become aware of in Sendak’s drawings that open up the world again of childhood learning. Sendak himself admits his debt to German Romanticism and particularly to Philipp Otto Runge (1777–1810). I discovered one particular Runge painting of 1805 that surely is a direct influence (in its representation of sunflowers alone even) on the illustration of Outside Over There and a starting point to vary its representation of childhood: Die Hülsenbeckschen Kinder (1805). We only have to gaze for a short time to see a painting where gaze is constructed for a purpose – to sell, I think, a notion of the nature of children deeply compromised by ideology.

‘Die Hülsenbeckschen Kinder’, 1805, Oil on canvas, 131.5 x 143. cm., Hamsburger Kunsthalle.

The ideological is moreover conveyed through looks – not only of the children, gender typed by their shoes and clothes, but, in my particular interest, their gaze upon each other and the outside world. A baby girl may be encouraged to look out on the world but otherwise a gaze that meets the spectator-of-the-picture’s eyes is only the young boy who is also shown as the agency required to do the harder work of pulling the cart holding the baby sister, though his slightly older sister seems responsible for the steerage of their way. And this is necessary precisely because of the need of the male to gaze upon the world and feel its gaze returned and justifying his foregrounding, as heir to his fenced home and property. He bears a whip in his hand to further assert his authority, though in play as yet, and, I think, the gaze upon him gets no nearer to him and the family group of which he can feel he is the defender by sexed -and-gendered nature and social authority.

His older sister takes the background. she seems crucial in the labour involved but is clearly not going to assert this point, but the important thing is the direction of her gaze. It is on the baby sister and speaks openly of her ‘natural’ duty of care and attention for this sister. Whilst she pays attention, whist she watches, everyone else, including the baby sister (until she grows into the social reserve supposed natural to adult femininity) can range the field with her wanton gaze, not even defensively. Does she even know defence is needed? For care and defence are delegated to the older children performing parental roles. As I gaze at this picture, I am almost sure Sendak would have seen this, so intense was his preoccupation with the unattended child, which he believed himself to have been, at least in terms of being emotionally held by his parents and which made his fascination with the tragic story of the Lindbergh Baby, known to influence Outside Over There, and written about at length as such by both Kushner and Cott.

No-one needs, least of all an infant child, to know of Charles Lindbergh’s disappearance and probable murder by his parents to know infants are vulnerable however, and Sendak seemed to be internally shaped by the notion of his own vulnerability and the need, as he felt it, for aggressive response to the gaze of others. I think this may have much to do in fact with growing up queer in a deeply homophobic society and extended family, the latter of whom he took as models for the ‘wild things’. I would assert, but I am intellectually formed, a bit like Sendak was much more intensely, by psychodynamic theory and its particular evidences - not least that of children by Anna Freud, Melanie Klein and the neglected Karen Horney, that children have a deep awareness of the meaning of facial gesture and body language.

That awareness is likely to be formed by interaction of genetic and environmental factors, whatever there dependence as developing beings on the care of others necessitates such skill, even the reading of ambiguity in the care given – between words and actions, actions and their styles of performance for instance. Moreover, they become attuned to identify their own emotional and cognitive state to the signs of those in the other in the role of carer, it is surely the source of the skills of introjection and projection, empathy, sympathy or that state of ‘not bothered’ they will play and use strategically in interactions with each other and with adults and as adults, for a long time. For the Hülsenbeckschen baby that would be be into the play of heteronormative symbolism already surrounding it – and enabling the development in all likelihood of a perfect example of bourgeois German wife-and-motherhood that would be cajoled into enacting happiness with her lot – denied to others.

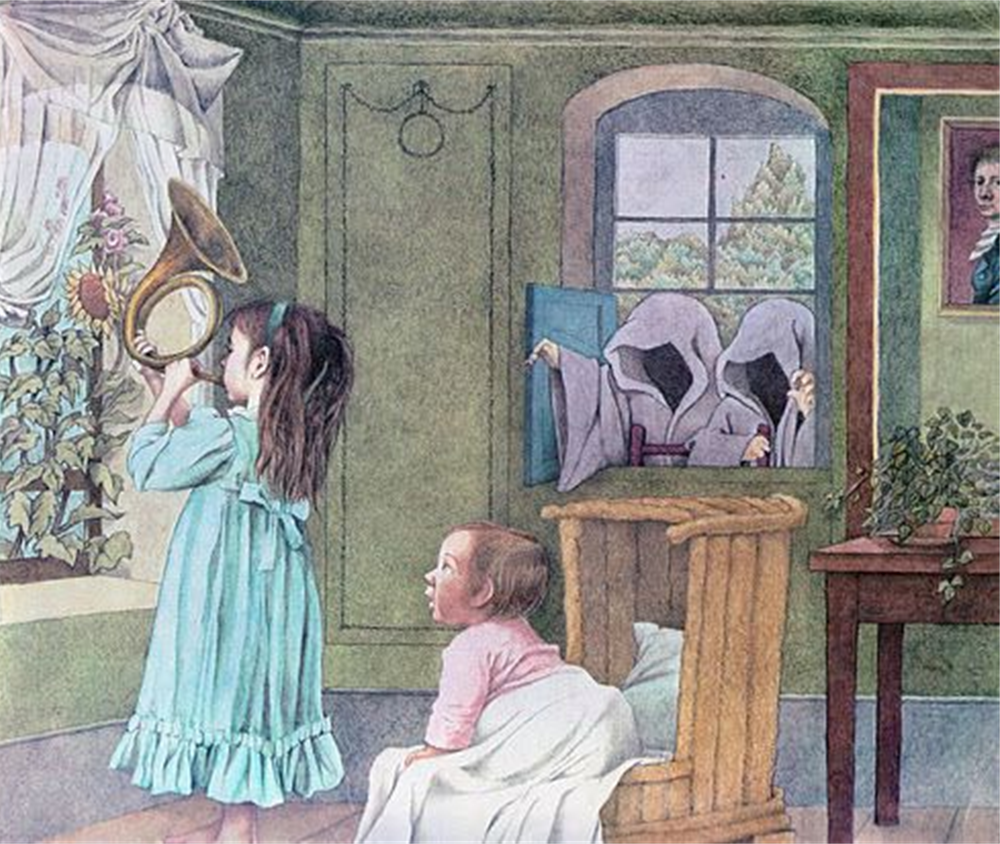

But I would be keen to insist that Sendak deliberately undermines the model of the child gaze, especially the female child gaze, in Outside Over There. But not everyone notices it because they look through ideologically tinted glasses. Let’s look at this picture (and later at one of its companions):

Sometimes one knows how a picture should be read by the reaction one feel’s over certain descriptions of it that just do not work for you and irritate you more than they should. Cott, telling this part of the story of the book says:

With Mama immobilized, Ida must tend to her sister on her own, so she carries the crying baby into the parlor (sic.), where, on the wall, a framed portrait of their papa is reflected in a mirror, and places her in a crib, then picks up her yellow wonder horn and turns her back on her sister to play a calming melody. But during this moment of distraction, the goblins climb into the room on their ladder through an open window and snatch the baby, …[1]

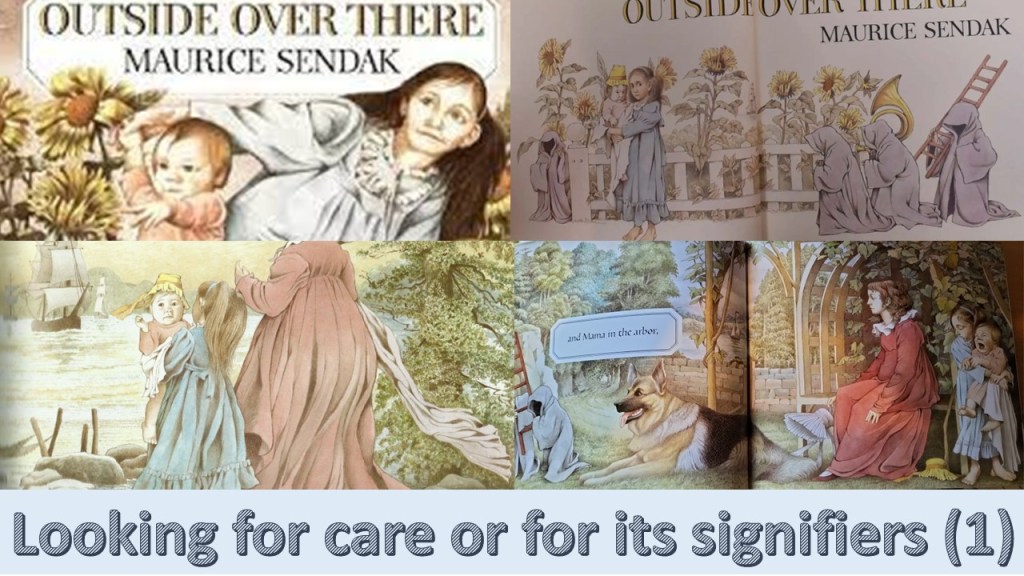

What literally infuriated me ere (rock me still, O Wonder Horn! – told you I was irritable) were the assumptions about the unseen actions before and after the scene we see turned solid in still time before us. This applies even their duration of actions (for who knows how long Ida turns her back on the baby – a ‘moment of distraction’, after all, sounds the like the excuse most people use for neglect of things they lose and are made to wish they hadn’t – because ‘moments’ can, in reality and in the recognition of the tiresomeness caring is sometimes, be felt to be as extensive as we wish them to be. In truth we, as simply people who look on this pictured scenario, without power other than to interpret with uncertainty, have no authoritative access. This extends in this description even to ascription of motives for action that we also cannot see because they are internal to characters whose inner life can only be assessed, and that uncertainly by reading gesture or expression or other elements of body language, including how clothes are worn or otherwise and objects held or not, and scenic proxemics that makes something of spatial relations of figure to the other characters or elements of the scenario. Yet Cott assumes a lot in a few words about how to interpret Ida, not least about the attitude of care that Ida has towards her sister. For if we have any evidence at all before we see this scene it is ambiguous at least, as perhaps all interpretations of what we only see must be. Here is what I see from pictures earlier than it, including those on the cover and prefatory material:

Compare Ida, the daughter who is our focus in Sendak’s book, to the older Hülsenbeckschen girl-child and the point is clear. Ida resists the imposition on her of a ‘feminine’ role assigned by her biology and its supposed functions in the view of the heteronormative model. She never really gazes at the baby, even in that crucial moment on the cover where she lets go, or is about to, of its hand, and thereby tests the baby’s capacity for taking on the stance and motive force of an emergent adult. Her gaze is dreamy but not one dreaming of the care and attention of a baby – a role forced on her by the absence of her sailor father and her deeply depressed mother. On the half-title page though she now carries the baby, her gaze has no sense of satisfaction in it. Though in this one, and in hot summer sun as indicated by the sunflowers (another immigrant from Runge), the baby has on its yellow sun-hat for protection, its ribbons are untied. Ida almost glares at us to show her dissatisfaction. Even more interestingly she can no longer carry the instrument of her pleasure (the wonderhorn), which is, for some unexplained reason being carried by the hooded goblins – so hooded in fact that they have no face or identity to look at as yet, just a dark void as Cott says.Is Ida in collusion then with the goblins, even if unconsciously.

In the first scenario that follows Ida’s horn is not visible at all and the gaze of all characters except the baby but including the goblins, Mama and Ida is out to see, upon which Papa is sailing like the sailed frigates we see, but Ida’s head is tilted away from her baby sister, who she holds precariously while standing bare-footed on a curved rock. The baby seems, like Charles Lindbergh to look out at the viewer in, as I would intuit, open appeal. Her eyes are tearful. I think it is clear that she does not feel securely held or loved, her sun-hat-ribbons still fly to the wind. She holds up her hand. For any viewer, and I think for a child, the baby appeals to be noticed. On the turn of the page (‘and Mama in the arbor,) because she is in shade Mama, deeply miserable in facial gesture and detached from the scene as we and she see it I think, is holding her own sun-hat, but the baby’d hat seems finally to have fallen off and the baby i drawn in some distress at a cause unknown. That hat will not be restored until it is put onto the changeling ‘ice-baby’ by, strangely enough, the goblins who steal the baby. Ida looks away and down from the crying baby – perhaps at the sun-hat, although it will not be on the baby at the next page-turn, and again holds the child in a way that looks both insecure and not really attentive to her sister’s infant squirming needs.Indeed the only thing paying attention is the beautiful Alsatian dog looking warily at the goblins moving away from the scene with a ladder that does not forebode well to the security of a house with open windows in the hot summer. My own feeling is that Sendak prepares us for the kidnapping by these very hints of a system of care that cannot work and is not motivated by a desire to ‘hold’ in either Mama and Ida. In one swoop, he abandons the notion of ‘a good enough mother’ (in D.W. Winnicott’s phrase that means a mother who ‘holds; or contains the baby and its emotional states) in her present state, or a substitute thereof in Ida.

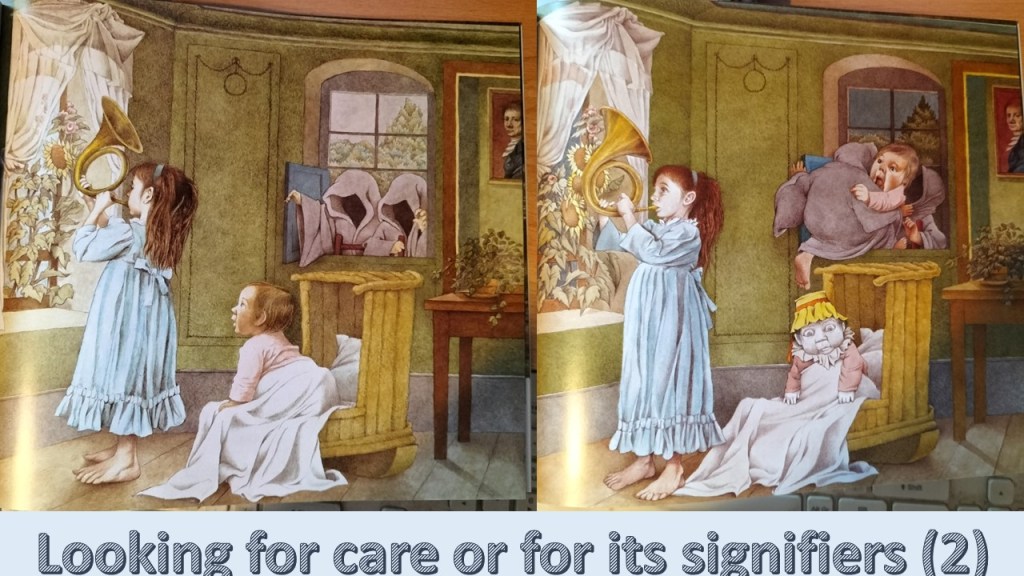

We turn the page now for the page described above in Cott’s own words. Below is that page and the one on the fold following. Both are on-page drawings with text on a white and otherwise empty page facing them: The first has the text:

Ida played her wonder horn

to rock the baby still –

but never watched.

In another blog in preparation I make much of the use of the word ‘still’ which is that of a poet (and indeed may have been learned from Sendak’s love of John Keats) but here I think I merely want to show how ominous is the final line, in the light of our attention to the gaze and looks of Ida, in comparison still with the Runge example above. To not ‘watch’ the baby has been illustrated in pictures before as I say above,but here the example is a gross one. Ida looks away out of the window beyond the sunflowers that beckon her, but it cannot JUST be ‘for a moment of distraction’, in Cott’s words, for in the next scene she has changed her position relative to window and cot and indeed is shown standing on the cot blanket with her left heel. This is then some distraction and its motion is the music of her play – not that of the intent to make the baby ‘still’ (motionless and silent as in Keats’ Ode to A Grecian Urn).Whist she has been moving lost in a gaze that looks away, though beginning to acknowledge us as spectator in the second one but only marginally and uncertainly, the goblins have got off their ladder, both clambered into the parlour, moved the blanket, taken the baby, replaced it with an ‘ice-baby’ (a term incidentally Sendak applied to himself) and carried in an ungainly clumsy way the baby through the window and back onto the ladder, while the baby cried out (for her mouth is open and even apparently pleading with an Ida who still ignores her) – the noise of all this seems conveyed in the plosive of Sendak’s text for they ‘pushed their way in’ and ‘pulled the baby out’.

The text above will be adapted for a blog that will take time but here I merely want to record how yesterday I learned to know that some skills of warily watching are probably ones that all babies know, and what Ida’s baby-sister knows. For you cannot trust adults to give up their independence as a baby and attend first and foremost to you. An this seems to apply to real rather than ideological girls – for the latter are a Romantic myth of reactionary meaning for the rights of women that was to storm Europe and allow for Romantic rebellion that extended largely to MEN not WOMEN, to Goethe’s Werther but not to overly conventional Lotte – who wants a stable bourgeois husband, to William, but not Dorothy Mae Ann, Wordsworth, his sister – nor to his wife. The work on infant learning and its interactions with genetics is contested but we know that mechanisms, such as imprinting (first noticed by Lorenz) show that infant goslings even inherit a behaviour that causes them to cling to the first carer they see to hope that will engender (and I use this term in lots of ways) being cared for and attended. I now, perhaps for the first time, see such primal learning, that Sendak seems to held in his intellect and emotions, that I felt I and my students noticed in the great Jane Austen was in reality learning I had, for good or ill (and given my sometimes mental states I think for ill, but NOT ALL THE TIME thankfully, since I was a babe insecurely held.

With love

Steven xxxxxx

[1] in Jonathan Cott (2017: 80) There’s a Mystery Here: The Primal Vision of Maurice Sendak New York, Doubleday

Once again this is one of your pieces that I will have to return to and re-read in order to appreciate fully. It has also resulted in a couple of books being added to my shopping list. Thank you for providing entertainment and enlightenment as always. Hope you have a wonderful Christmas.

LikeLike

Dearest Kea. You are a friend. Kind and a bookish soul mate

LikeLike