‘These words that sculpt us from nothing but silent matter into monsters’. The art of Gary Indiana in To Whom It May Concern (2011) London, Violette Editions (still available it seems) a co-production with Louise Bourgeois.

Louise Bourgeois with that phallic monstrosity of a sculpture, ‘Fillette’ (‘little girl’) she carried with her frequently, and Gary Indiana both older and younger.

In Gary Indiana’s novel Resentment: A Comedy (1988 in the UK), which though brilliant takes some stamina and / or enforced pace to read, a young media star named in the novel as JD, still working in radio at this time in the novel, is interviewed by the character Dylan. His gestures seem to communicate at the same time as he speaks but on a different channel, as with this example of his articulate and voluble ‘smile’: ‘JD says this with a smile that says: I’m not the monster you take me for. But I am a monster, just like everybody else’.[1] Gary Indiana believed that modern culture was inhabited by MONSTERS and that it was endless speech and noisy typing that often produced those monsters.

Take, for instance, Resentment: A Comedy itself, focusing on the discourses spawned in California by a notorious and bloody murder of their parents by brothers, who sleep tightly bound together. The book also includes the making of a film of the murder and trial, clearly showing how a society that is drowning in its own self-articulation makes monsters of those who feed upon and re-excrete what is said so much and so volubly. Everybody and everything speaks all of the time and without a break. Even the prose style is voluble. One sentence conjuring the ‘terrific fracas’ in the pressroom of the court at the brothers’ trial, has a sentence that spans three tightly-printed pages where everyone constantly talks and ‘spins’ on what everyone else talks and ‘spin’s in lieu of substantially real communication, or social communion. The sentence focuses on re-performance of speaking and writing intended merely to fill silence. In this part of its duration it focuses on the journalistic and storytelling legitimacy of a press celebrity called Fawbus Kennedy:

who mainly writes a lot of unsubstantiated gossip in what Seth calls that putrid magazine and once every year or two produces a Jackie Collins type roman à clef about family scandals of the rich and famous, though compared to Fawbus Kennedy, as Seth puts it, Jackie Collins writes like Michelet, …. (and so on for another two pages).[2]

Put that fact into the context of the piece from To Whom It May Concern I quote in my title and the concern of this work with how endless breaking of silence ‘monsters’ us, even in the most intimate of relationships and explorations of self and the boundaries between selves is clarified: it as if the ‘silent matter’ of our humanity – constituted by our fleshly bodies perhaps – which feels solid enough in its silent expression uses the stuff that words intrude into the gaps between and within our bodies to transform us into monsters. Because words don’t have to be written or spoken to exist: they do nicely for themselves living in things like thoughts, memories and ‘minds’ (even in the very visceral matter of our brains that perform those activities of coding). And, strangely enough, even art is complicit in that intrusion in the insistence on solidity and its shaping in this sentence – in its use of the word ‘sculpt’ – especially when collaborating in a collaboration between a writer and a sculptor in very many media, like Louise Bourgeois.

Moreover, the transformation of solid media, even the silence of a blank page, into ‘monsters’ is analogous with such sculpting. Monsters are things that we create when we believe ourselves to be expressing honest feelings, basically love and hate, but in doing so engender many perverse forms of the embodied life we share, silently sewn together, like the corpse of Frankenstein’s monster from any other body parts alien to each other and made nevertheless to speak. At this part of her career, Bourgeois was sculpting and drawing (though these were allied projects) by creating solid collages out of fabric but even her painting was about the submergence of disparate media into an emergent whole still bearing the marks of its creation from many parts.

Anyway, at root, we might ask, doesn’t all communication which pretends to clarify and build bridges between embodied persons, actually obscure and bury all connection? We shall see this in Indiana’s words (‘These words that sculpt us from nothing but silent matter into monsters’) and Bourgeois’s digital artworks. At this point, we need perhaps a rather long factual discursion into what the book we are thinking of in particular in this blog IS. This ontology is by no means easily discussed and should ideally involve thought about the nature of artistic collaboration across space and time as well as in production – of the role in art of copying and reproduction, such as are raised in Robert Shore’s stunning book of 2019, Beg, Steal & Borrow and was Picasso’s constant confession. But that is too big an ask here. So I proceed with facts alone, and for that we need to look at the original book (there are only 7 copies) since I possess only the trade edition (of which there are 1500):

To Whom It May Concern (2009-2010) Gary Indiana / Louise Bourgeois, on Fabric illustrated book with 12 Digital prints, page (each): 16 15/16 x 11 13/16″ (43 x 30 cm); overall: 17 5/16 x 12 3/16 x 5 7/8″ (44 x 31 x 15 cm). Pictured next to trade edition cover (1500 copies).

When Louise Bourgeois was approached by Carolina Nitsch, the publisher of To Whom It May Concern, to nominate a writer to collaborate on a book featuring her art she chose Gary Indiana because she liked his work. The trade edition of it published in 2011 (an edition limited to 1500 copies has its front cover pictured bottom right above. Amazon still advertises them for sale by the way. This book was based on an original (pictured to the viewer’s left above of 7 copies only) of which the one pictured above is number 7 and belongs to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, gifted to them by Indiana himself. The story of the origin of the book is told in MOMA’s website:

In 2009, Bourgeois began drawing male and female forms in profile with crayon, colored pencil, gouache, and watercolor on paper. The fabric printing workshop Dyenamix digitally printed these drawings onto fabric. Bourgeois worked with these compositions in unique prints,…. Gary Indiana was shown these works, for which he wrote corresponding text to create the book he titled, “To Whom It May Concern.”

Reading it and examining the printed pictures thrusts you into considerations of the materiality of the art involved as well as considerations of the meaning of creative authorship and the fabrication of art works, as I have already suggested above. Bourgeois sewed her initials into the 7 copies (Indiana signed it only in pencil) but the responsibility for its ideas is deliberatively I think obscured between them, as is the idea of which versions of the artworks or text across the production of the book can be thought of as original works – those dyed onto fabric in copies like MOMA’s by Dyenamix, the original pieces drawn in ‘crayon, colored pencil, and watercolor on paper’ or the digitally printed copies of the final trade edition. Whatever, it will be difficult to feel that you have seen the version intended, and even more so given that my reproductions, downloaded from MOMA’s website are re-collaged. Their colours and tonality are, to my eye at least, not consistently aligned with the digitally printed ones in my copy and may not be to the MOMA copy either. They will however give some idea and this warning is enough to mean that interpretation of what we see probably changes in transition to another medium and mode of making. Indiana stressed the idea in his interview with MOMA of materiality with regard to the book and the co-producers’ intentions, saying:

On the format of the fabric book, Indiana remarked in the same interview: “It’s an incredible object. … [it] had this ‘thingness’ to it that was heavy … when you turn the pages they’re considerable … it has this physicality to it. And, you know, the whole project was about physicality, in a certain way.”

The idea of how the physicality of book production aligned with both those of Bourgeois’ (in the use of mixed materials and surfaces to recreate bodies in some kind of interaction and contrast) and Indiana’s use of words to evoke visceral response is something that it may be worth considering. We know that he wanted the book to look more ‘handmade’ and for this reason he chose that the typeface named American Typewriter to distance it from the contemporary.

However, I think authorship becomes even more complicated when we think of how each artist contemplated and recreated the world of each other’s sensations as well as themes – there is something in the intrapersonal interactions described and visualised that relates to the themes of interpersonal communication and contact between bodies and everything other than body that gets involved in that interaction: senses, thoughts and actions that get articulated before they are, ostensibly, communicated. The MOMA summary describes the process thus:

As Gary Indiana worked on the text, he considered not only the compositions Bourgeois created for this book, but what he believes to be a major concern in all of Bourgeois’s work, which he described in a 2011 interview as “… a kind of unclosable wound, and a kind of perplexity and paradox of one’s relationship to the other. To any other, but, you know, particularly to the loved other and the hated other”.[3]

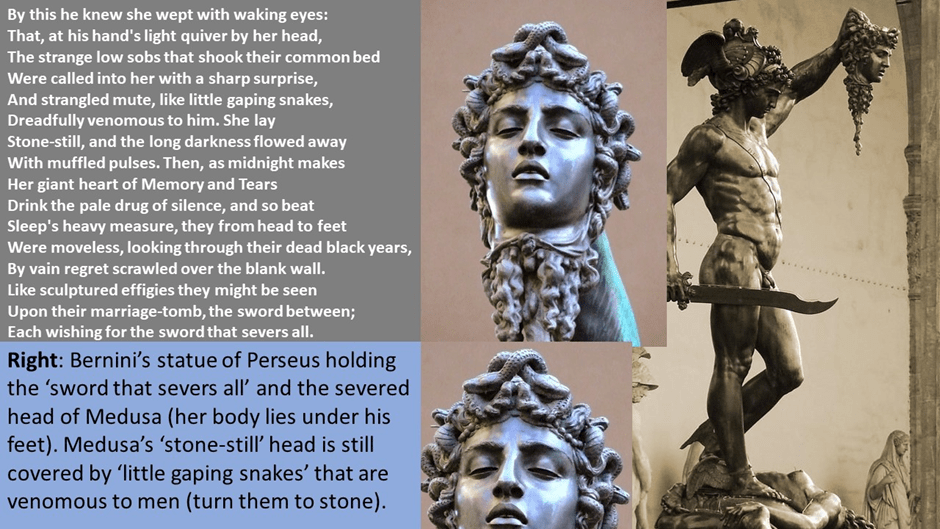

The idea of a flesh wound on the body still open or inadequately sutured will take us back to the notion of Frankenstein I invoked above and to the fabric sculptural work of the late Bourgeois. But it is also about in both artists other open body wounds – the orifices and holes of the body – which will resurge throughout both writer’s works and link them both to deep interest in ideas of life and death, growth and decay, sustenance and excrement, and, of course, original and copy (reproduction in many senses). In my view the nearest work to Indiana’s is actually a much older and much neglected one, George Meredith’s Modern Love, which also uses the imagery of sculpture (monumental sculpture in the latter case) to illustrate the cusps of speech, thought disturbing the supposed silence:

By this he knew she wept with waking eyes:

That, at his hand’s light quiver by her head,

The strange low sobs that shook their common bed

Were called into her with a sharp surprise,

And strangled mute, like little gaping snakes,

Dreadfully venomous to him. She lay

Stone-still, and the long darkness flowed away

With muffled pulses. Then, as midnight makes

Her giant heart of Memory and Tears

Drink the pale drug of silence, and so beat

Sleep’s heavy measure, they from head to feet

Were moveless, looking through their dead black years,

By vain regret scrawled over the blank wall.

Like sculptured effigies they might be seen

Upon their marriage-tomb, the sword between;

Each wishing for the sword that severs all.[4]

It is a fascinating example of where the ‘stone-still’ suggests both the motionless and silence simultaneously that nevertheless shows that living bodies that think are never quiet, never without words in the state of being simply matter and not instinct with consciousness of knowing and sensing. For we cannot even conceive of such a state of being. Even the ‘sculptured effigies’ of this sonnet are longing for phallic severance: divorce and death both that ends the conjoined life aroused in the verse. It is aroused in the rhythms of the verse that animates sensations: ‘muffled pulses’, ‘low sobs’ and the ‘heavy measure’ (‘measure’ of course being also the term metre as applied to the verse line) of heartbeats and the presence of thoughts that will not turn to stone or be still. Hence those unheard thoughts are felt, most noticeably in the suppressed Medusa symbol under all this: ‘And strangled mute, like little gaping snakes, / Dreadfully venomous to him’, a snake-haired woman turning men to stone.

So I think again about Indiana’s sentence: ‘These words that sculpt us from nothing but silent matter into monsters’. Next to the Meredith example, we might think about how Indiana told MOMA he thought about the meaning of Bourgeois’ work being the revelation in relationships of love (both romantic and sexual) of: “… a kind of unclosable wound, and a kind of perplexity and paradox of one’s relationship to the other. To any other, but, you know, particularly to the loved other and the hated other”.

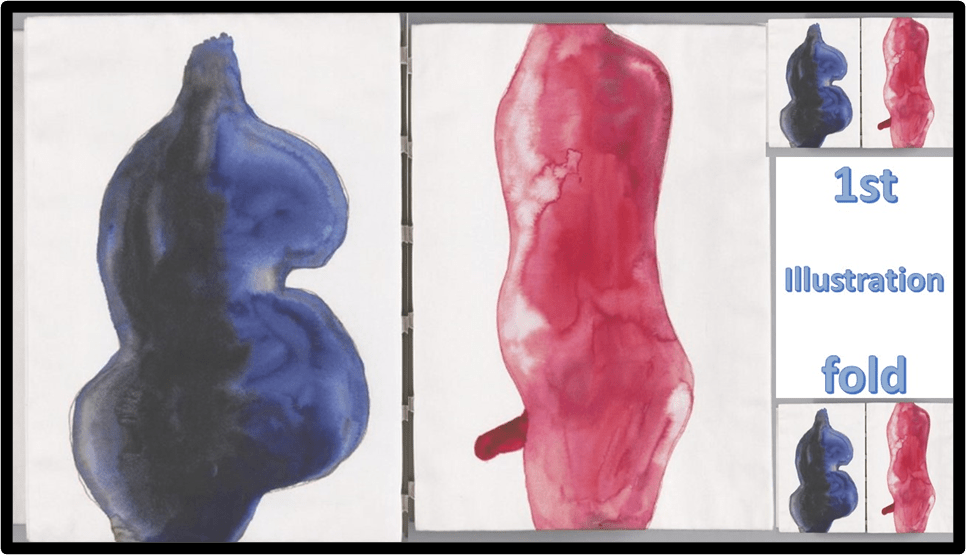

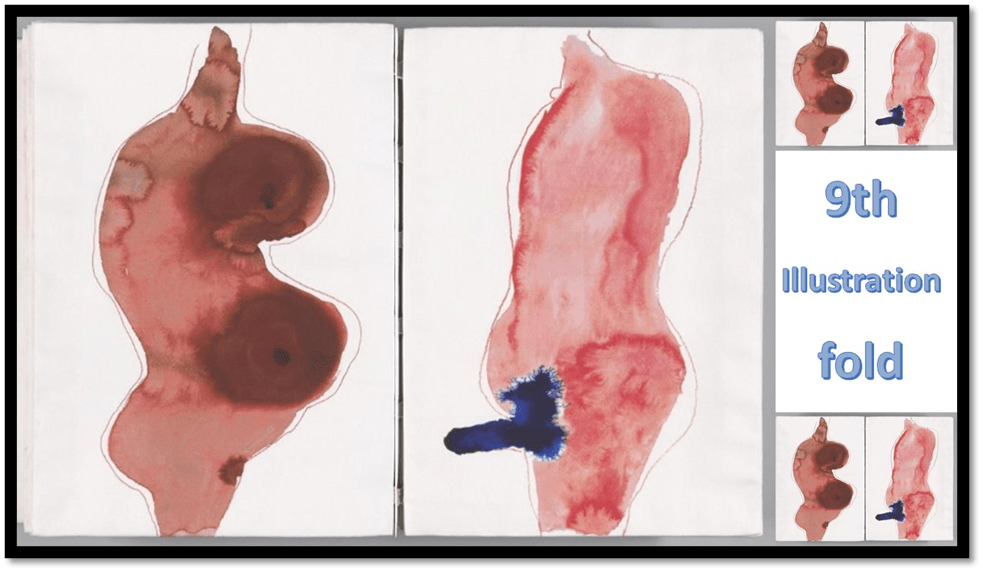

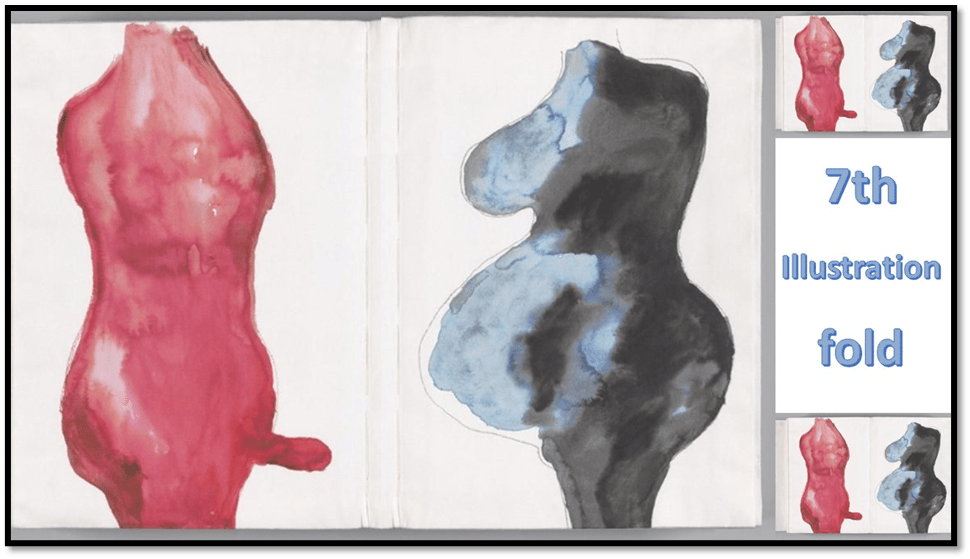

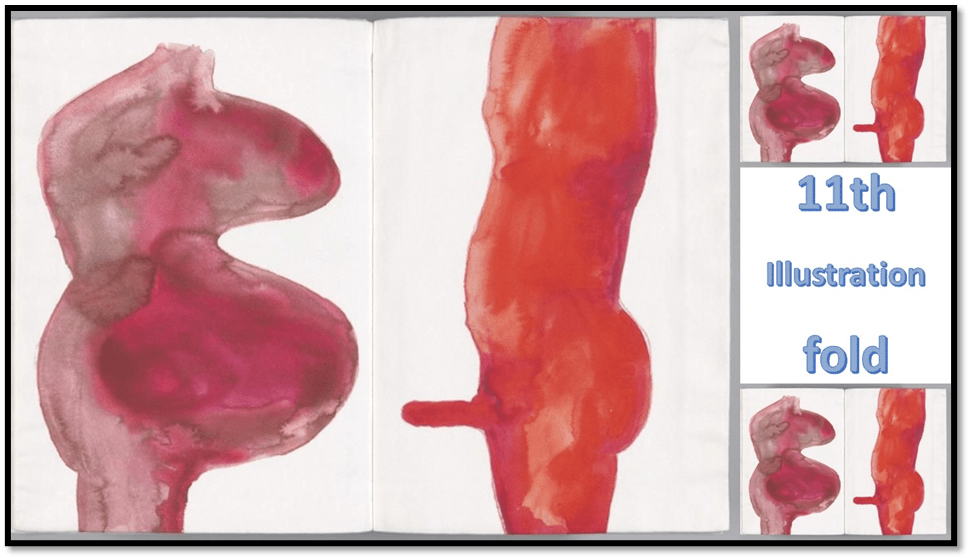

Bourgeois’s digital work in the book imagines twelve examples of different bodies in pairs or dyads in proximity and facing each other. This is captured in the prose-poems of Indiana in moments where mental activities of all kinds attempt to interpret distances between bodies. And his articulated and structured words organise the body in the same way as Bourgeois does; in terms of mutually unpenetrated and untouched body surfaces where body parts often sexualised (and seen as makers of biological and social sex/gender identity) are quivering with conscious nervous or unconscious neuronal potential. Thus the page fold that shows the first dyad of Bourgeois’s imagined body forms is preceded by a prose poem that metamorphoses the space-time between Bourgeois’ painted bodies into the silence between a couple before sex, filled with complex sensations, feelings and thoughts:

He sometimes imagines that the silence before they come together resembles the quiet of a bullfight just before the matador and the bull comprehend where they are and sense what is about to happen: electricity moves invisibly in the air. … Limbs, skittish, nails, swatches of flesh, some dry and rough, some slick, slippery with perspiration, unknown curvatures and declivities, motions that sputter and retreat, others that unspool in quick episodes of frenzy.

The encounter between matador and bull leads to the inevitable death of the bull and a little uncertainty about the likelihood of the matador’s possible death. However, the issue with sexual coupling is often both the desire and fear simultaneously of abolishing the space-time between people, including that imagined and remembered space-time they treasure and secrete inside their bodies. It is the slippage between insides and outsides that the prose begins to work up into something truly fearsome, such that the moment of encounter is as much about the potential of ‘separation’ (drawing apart) as coming together: attachment and detachment. And it is visceral with some of the pulse of the Meredith sensed in the inner movement of body fluids, where space is felt as time and vice-versa:

The gurgle of inside his body, the space that opens between them and widens impossibly until it becomes an essence of separation, an impassable desert where the life of inert objects reasserts itself and bespatters time. / The pockets of solitude, bulging with memory and fear’.

And then we get Bourgeois:

What happens here is that feeling and sensation, and even thought, get turned into texture. This must have been the more poignant in the original copy where to turn the pages was to feel the linen which formed the printed page. Indiana can play with these correspondences, where before the next pictures he says, confounding the word ‘feel’ between its interpretation of a sensation of touch to one of inner emotion: ‘feeling depends on the texture of this quiet, the faint rustle of linen wave-like soughing or blare from streets below or rain …’. The senses of touch and hearing confound here and remind us that ‘texture’ applies both to the feel of fabric and the construction of ‘textual texture’ from words – the texture of rhythm or assonance for instance in the mouth, even when text is unvoiced.

Those bodies shine with the aura of resistance surfaces, although Bourgeois creates a gap between the boundary line defining her female figure’s breast and distended lower torso which the male figure does not have in this dyad at all. Both however have a sheen of impenetrability, although the male’s anal orifice is defined by patches of white. There are near fissures in the skin of both relating to the unevenness of the dyeing process reproduced on these figures that at one stage of conception were fabric.

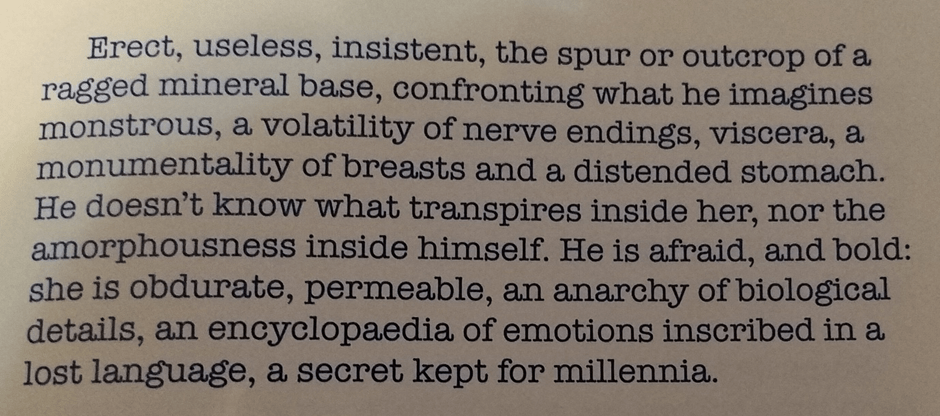

The passage that follows this set of figures is the most easy to read and interpret, I think, than others for it turns matter, expressed as that of a landscape or statuary (as in ‘monumentality of breasts and distended stomach’) into the imagined body seen, as it were, neuro-muscularly just under the surface of the skin. What is being opened up between them though are different languages in each other that the one evoking them may not understand, being a ‘lost language, a secret kept for millennia’. But lost in thought, even without words between the bodies, the words that imagine another, create a monster – the woman’s body as ‘monstrous, a volatility of nerve endings, viscera, …’.

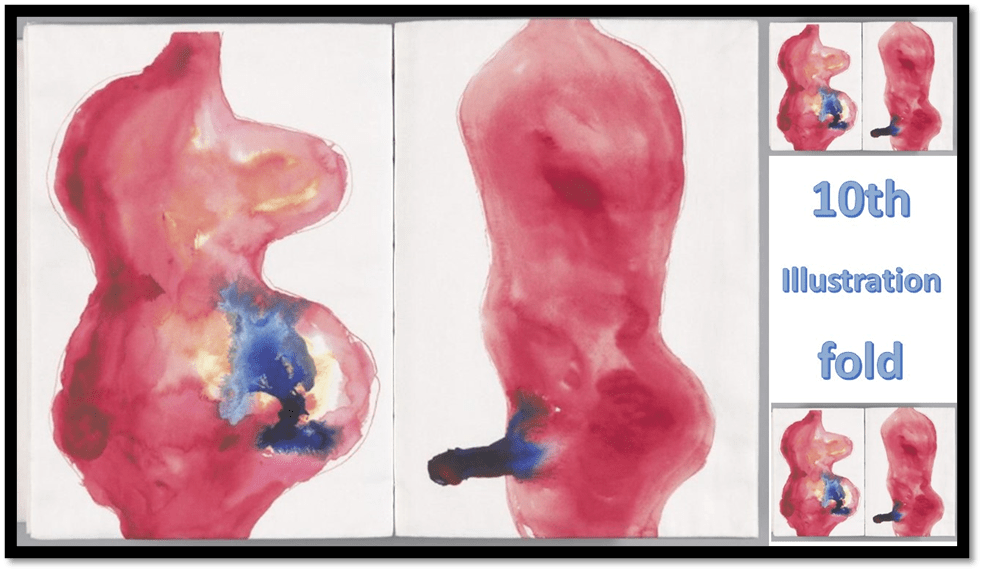

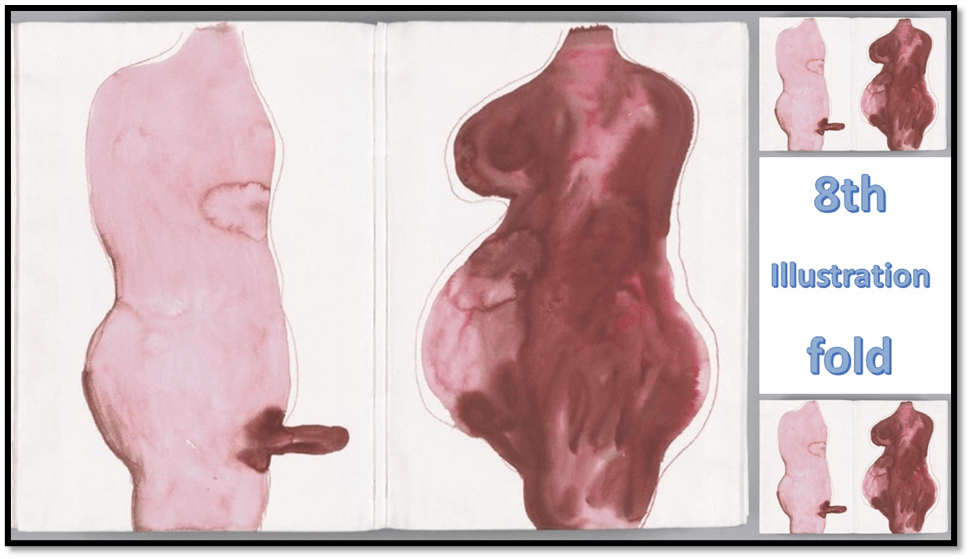

Just after Indiana mentions ‘texture’, the texture of the digital surface of Bourgeois’s next dyad of body forms dramatically changes (much more so in my trade version copy than that below). The sex/gender position on the fold is reversed and the male body form is no longer coloured to fill up the space withing the thin defining line, though the angle of the penis is more insistent and a staining of colour has begun to define the female’s vagina.

The variances of the female form’s interiority seems more pronounced in this dyad, even flowing out to her surfaces. Indiana’s prose turns to more concern with what, if anything and when, is hidden inside or within. He insists it is the encounter of selves that in fact creates interior selves within each person: ‘This “within” isn’t anything until I revel it. A slaw of transient moods and simmering impressions. Until I’m with you, or someone else, or many others, I don’t know who I am’. The fact that the union of selves is both intimate between two selves and that this masks the fact that Bourgeois’s forms continually vary in shape, colouration and other ways. That ‘coming together’ is not a sacrosanct marriage but may continue in process between differentiated forma of love-object; ‘you, or someone else, or many others ‘. The next page fold has figures of similar colour (though tonally quite different within their boundaries, but both marked as with phalli (again variant). The space between them is filled with an excrement that may or not be that produced by orgasm. It seems a monstrous growth of extended skin, or biomorphic parasite, that only connects in complicated ways with the productive end of the phallus.

This is the only pair of figures that seems to represent a male-with-male near-encounter. The only hint of the meaning of that projected shape on the first figure’s phallus is actually about how very basic words relate to monstrous recreations of each body and the two bodies’ relationship: it muses on the creativity of ‘I’ and ‘we’ and the engendering (even ensexing to play a post-structuralist language game) of bodies; possibly not just on sex or romance but in aesthetic collaboration such as that between Bourgeois and Indiana.

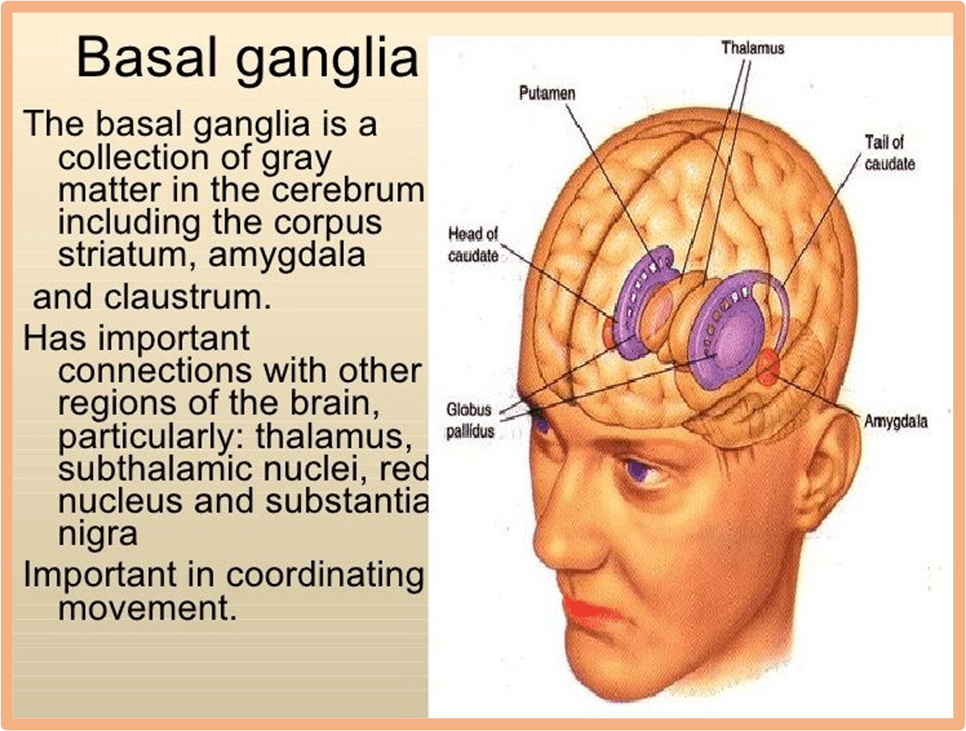

The body even forgets the body, … It’s a monster of regeneration, a freak of neocortical industry, a factory of endless self-production, “I”, “I”, “I”. It cannot be otherwise, it only pretends to become “we,” even if I create you and you create me. “We” is the puppetry of “I,” dangling on ganglia of how and when and where.

Never has neuro-biology (even morphed linguistically into ‘neocortical’) become so mixed with metaphors of production and making and reproduction. If whether ‘creation’ is equivalent to ‘making’ remains an open question, the playing-off of issues of space and time on method (‘how and when and where’) means that the whole can become internalised as the operation of neuronal ganglia, which the projection on the former picture might suggest (it has the look in part of that central structure in motivated mobility – the basal ganglia shown in the illustration below).

This kind of play between differences continues following Indiana’s prose-poems which confuse sex/gender with time and place that follow. However, it also confutes, although it is unclear whether this was shared between the collaborators, secret experience of Indiana’s with those of Bourgeois, for in his very recent memoir, Indiana revealed the importance in his sexual life of a group of young men who were called, in the Cuba he knew, sordomudos, or, in his experience, young men who were also deaf and did not use spoken language and who consorted together. The men in his memoir were also in the economic circumstances and for other cultural reasons according to Indiana also ‘rent boys’ (or pingueros in Cuba). Among those was a lover he was especially attached to, Mastiu (‘a man who did not hear more than small pieces of what those around him said’ in To Whom It May Concern below).[5]

Another time, another place, another woman, if it is a woman, I cannot now recall, telling him, if it’s him, about a man who did not hear more than small pieces of what those around him said.

Such queer shifts of sex/gender were common though in the experience of both artists in life and art, although Indiana predominantly had sex with men according to his memoir and certainly wrote pioneering novels of queer life, such as Rent Boy. A ‘monster of regeneration’ is a good metaphor however for all kinds of reproduction (sexual, social and economic, genetic and memetic) important in this artwork and the next set of forms returns us to the female figure with distended lower torso.

In the shift between the fourth and fifth dyads though that ‘distended lower torso’ begins now to insist that it is a representation of late pregnancy, for it conveys the inner space which may be that to be filled by a new life.

It would be unnecessary, having gone thus far in telling a selective version of the ‘stories’ of this book to continue to do so, for they will vary between readers necessarily, the book itself demanding mergence of reader/viewer and writer/ plastic visual artist simultaneously in its becoming the thing of ‘terrible beauty’ and meaning it is. One beautiful prose-poem examines story telling by querying the fallacies of the storyteller’s paradigm: ‘Once upon a time: …’. So I want to be even more selective. One moment involves two closely linked dyad forms I will show below. The missed dyadic forms appear in an appendix (6, 7, 8, 11, 12). However, I do want to pick out these two linked visualised dyads of Bourgeois’s that so frankly link the sexual openness of both artists with the notion of the fear and desire of sexual interpenetration, and internal sharing which that involves. In both cases sexuality is linked to creativity (reproduction and engendering). The first follows a prose-poem imaging the creative mind as accessed through the vagina and by a projectile (a ‘cunt’ and a ‘dunghill’). These pieces not only confutes space and time in the manner of the imaginative act but also the promiscuity of continual giving and receiving in and between sex/genders (see my italics below) and varying objects in imaging the love of an ‘other’:

If not here, not far. If not just then, not so much later. If not because of them and there, then you or him or her, some other place obscured by mist or vapors (sic.), some woebegone slag heap od fecund dunghill of abracadabra. And over there in a direction that escapes me my cunt gave birth to all the world, unless I am mistaken. If something else engendered it so much he worse, and let the miscreant responsible speak up.

Between the illustrations on the ninth and tenth fold, we see the penetration of genital sex prefigured in both bodies . However, the riches of each page are surely (certainly) not exhausted by that poor and thin observation of mine.

In the next picture the ‘cunt’ (though shown in brown stain above in the ninth dyad – mirroring breast and womb) is displaced – almost sealed up and displaced by the internal ganglia of the vagina as a creative set of internal organs, a ganglia set like those operative in the brain and gut.

If you read this book notice how, when it ends, it seems in the process of re-beginning: ’Whither and when, to begin. As when words fail and fall’. It ends with a weird ‘coming together’: ‘Because we have arrived. After setting out and blindly groping through abyss’. All this feels somewhat like a writer under the influence of T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets, but it ends locking everything inside the collaborative ‘we’ statements it achieves, with an enclosed ‘secret only we will keep’. And so it should be, except that the last words are:

Ours.

At last.

What is this ‘Ours’? My own feeling is that it intends to point to, at least, the:

- varied dyads of lovers, whether couples per se or a interchanging grouping,

- artistic collaborators Bourgeois and Indiana, but also,

- reader and writer, all combined with the viewer and visual artist in a grand foursome.

Enjoy it, please. There are still copies advertised on Amazon remember and other booksellers may source it. Of course there are also second-hand dealers.

With love

Steven

Other Bourgeois blogs by Steve are:

Tate Liverpool Artists Rooms exhibition 2021

Hayward Gallery South Bank London ‘The Woven Child’ visited 2022

A book on her painting by Briony Fer:

Appendix:

[1] Gary Indiana’s (1988: 85), Resentment: A Comedy London, Quartet Books Limited.

[2] Ibid: 95 (for whole sentence see 94 – 97).

[3] Indiana, Gary. Interview by Chrissie Isles, Anne & Joel Ehrenkranz Curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. 192 Books, New York. 2011 cited at: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/155776

[4] George Meredith ‘Modern Love’ Sonnet 1 available with full text at: https://genius.com/George-meredith-modern-love-annotated

[5] See Gary Indiana (2015: 130f.) I Can Give You Anything But Love New York, Rizzoli Ex Libris.

Nice 👌

LikeLike