There could never be only one thing that I might wish to change in the conduct of my life but, to tell the truth, I think the notion anyway of doing it by changing something you think of as a unified, integrated and whole ‘self’ is, in part at least, more of a fiction than a socially observable or privately felt reality. For many years I have been inclined to think of ‘self’ as a thing better described as a ‘distributed’ rather than integral whole, although my view is not not a radical one, nearer to this recent conclusion by Regina Fabry who argues for:

a new account of distributed self-narratives that emphasises the important role of distributed autobiographical memories for integrating and connecting life events and experiences. This account would be consistent with more recent work on (sense of) self that refrains from postulating the narrative self as a robust entity, while still acknowledging the relevance of self-narratives for our temporally extended mental lives.

Regina E. Fabry (2023) ‘Distributed autobiographical memories, distributed self-narratives’ in ‘Mind and Language’ 38 (5) 1258-1275. This quotation from online publication (First published: 25 January 2023: https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12453).

Although this is a very abstract start to my answer, I think it is necessary, for the issue of personal change is far too often oversimplified by assumptions that selves are simple things that either WANT to change or not. When I trained social workers, I used to start by breaking down a common joke about the profession which which goes like this:

It is a joke, of course, (except that in 2004 the press found that actually to change a real physical light-bulb did, according to health and safety procedures, take many social care workers, (use the link to read the story) but the humour depends on a real problem – that so much of our belief about the care and support of others depends on us thinking other people are simpler entities than ourselves and can be governed only through themselves – a truly authentic centre of consciousness that can and will be the only focus of change. Popular memes take up this theme even more simply, urging us on to motivate change from within an entity thought to be at the basis of all life. They are given no greater resonance or authority even when backed up by celebrity, for in fact in the instance below, Ru Paul is possibly the best instance of a person dependent on the notion of a complex self than easily reproducible memes:

Nevertheless, the meme sinks so deep that lots of us are still convinced that when people WANT to change, we assume that they will. We rarely go on to ask and yet most often we still do not know how much and in what ways and with what quality that desire to change will change one or more of their behaviours, feelings and thoughts (and the various interactions between these factors), and in which social or environmental contexts. It is a complex issue rightly understood, and hence the abstract start. I think the modern world is better equipped theoretically to answer this question and less burdened by the usual models of the unitary self, like a militant monotheism. Yet we prefer to think over-simply. I ought to start by a piece of self-criticism. Lately I have been hurt by the rejection, without a explanation that was addressed to me directly, of me and much I think and feel by a dear friend who I loved in every which way you can love. In truth I still love him.

However, in the pain of severance I took to complaints about the effects on others (of course I meant me) of narcissistic traits. But that was unfair (see an example at the preceding link). What I said may have some limited validity but, in truth, it was just a way of providing an explanation that gave closure, which I felt deep pain in lacking. But narcissism is too simple an enemy. Yesterday I started reading a wonderful book by Matt Colquhoun called Narcissus in Bloom, about which I will blog when read.

Though really a book about the presumptive meaning of the ‘selfie’ in our culture, taking in the history of self-portraiture, on the way, it argues, from its introductory chapters that we have grossly over-simplified the idea of narcissism, even in its classical and botanical origins. It’s presumption is that narcissism is genuinely, even if based on a temporal fiction of the united self (such as Fabry posits above), complex and, for each of us, contains, if we maintain a simplistic attack on it, a ‘squandered potential’ that shows that it is implicit in our continual re-discovery in ourselves, and others, including marginalised social groups, ‘against all odds, that we retain a capacity and desire for self-renewal’. Indeed, we need to think again about the significance in Freud’s thinking (that I have not yet found in Colquhoun’s account of that thinker) that the ‘I’ (‘ich’ in his text or ‘Ego’ in most English translations) has its origins in ‘primary narcissism’.

What this awakening of the flower of thought has gifted me today as I address this question is that I find that there is something I might want to change in the way I keep on reproducing slightly variant versions of myself in thought, story or dramatised action (how, that is I present myself in those things) without any pretension to a project to ‘change myself’ or to understand what that might mean.

Of course, a life-project of trying to be authentic in relationships with as many people as I can, and who want that relationship, continues – which rarely includes institutions that mould us as workers or as ‘subjects’ of governance, where I still find Althusser’s thought (dependent of course on Lacanian psychoanalysis) about the ‘interpellation of self’ convincing. Yet the ethics of self-representation of self remain. To me they are still best represented in words by George Eliot about how moral thought is embodied in people – an idea I think she extrapolated from Feuerbach after she translated his The Essence of Christianity.

We are all of us born in moral stupidity, taking the world as an udder to feed our supreme selves: Dorothea had early begun to emerge from that stupidity, but yet it had been easier to her to imagine how she would devote herself to Mr. Casaubon, and become wise and strong in his strength and wisdom, than to conceive with that distinctness which is no longer reflection but feeling—an idea wrought back to the directness of sense, like the solidity of objects—that he had an equivalent centre of self, whence the lights and shadows must always fall with a certain difference.

George Eliot ‘Middlemarch’ Chapter 21: For whole chapter – https://www.sparknotes.com/lit/middlemarch/full-text/chapter-21/

Casaubon, Dorothea and Will Ladislaw in the wonderful BBC adaptation

Chapter 21 of Middlemarch, from which this quotation comes, is about a moment where Dorothea, now married to the dry old cleric, Mr Casaubon (whom she married because of her belief in his intellectual work), ‘honeymooning’ in Rome and becoming exposed to criticism of Casaubon as totally out of date in his thinking by his nephew, and the man she will, in the course of things come to desire and love, Will Ladislaw.

The context matters because this paragraph is not, as it is usually treated in the form a GOODREADS quotation, a sign of moralistic authorial intervention, about understanding how an independent ethical principle becomes embodied – in Dorothea now aware of her body, its desires and their frustrations, thinking new, strange and ambivalent thoughts and sensations about a man she, for the first time sees as embodied.

What Dorothea experiences is not a break-out from narcissism as much as a breaking-through into her consciousness of interactive embodied senses of another whom she prided herself on knowing before being wedded to him but now knows she did not. George Eliot stands up as an intervening authorial and ethically authoritative narrator in order to represent the fact that some social duties are sacrosanct – not least the need to see and feel the reality of diverse others, even ones as unpalatable as Casaubon. We only refuse to know this is a duty she says because ‘moral stupidity’ is innate. That ‘moral stupidity’ is not narcissism, it is much nearer to a more appropriate adjective for our capacity to enable sensory deprivation in ourselves to the embodied needs, wants and desires of others – of every kind – and to know that they are as focused just as much in an ‘equivalent centre of self, whence the lights and shadows must always fall with a certain difference’.

I love the rhythmic beauty of that last sentence and in the novel it works even more beautifully for people in it are often seen emerging into an amalgam of light and shade both inside and outside buildings or rooms, and inside and outside of their bodies. If you are ethical, George Eliot knew, you are so because you think differently, in an entirely physically embodied way. For only the latter has the ‘distinctness which is no longer reflection but feeling—an idea wrought back to the directness of sense, like the solidity of objects’.

So what would I change? I would try to better understand that we should not use the world as an ‘udder’ to feed and milk our selfishness. The fact that this world is a ‘mother’ has not escaped George Eliot, for I think she did see mothers in our patriarchal world as trained to feed predominantly male selves out on the make into the selfishness capitalist ideology prescribed. These lads remain glad they had that womanly support, and, so long as Mum stays in the background, she can remain a lifelong udder physically and eventually in our internal psychology.

I think Eliot understood too that women who wanted intellectual independence, as most of her heroines did as well as Eliot herself, could be (and maybe had to be) equally abusive to the sustaining biologically feminine, and the patriarchal value systems that made their biology most women’s only option in life, the udder (rather the angel) in the house.

Selfishness is not self-love (nor narcissism) but something else – a construction of ideology that makes capitalism seem natural and makes Sir Keir Starmer (imbued as he is with the notion that only a selfish motivation can engender change) praise Margaret Thatcher, as he did today. Combating ‘selfishness’ then and its sustaining ideology, which Marx in the Grundrisse saw in the proliferating Robinsades (stories of a man stranded on a desert island and inventing society anew from that root like Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe). That latter-named novel, by the way, also manages to naturalise colonialist imperialism and racist exploitation and power structures. Robinsonades make the pretence that society is born of one man’s instinct for self-betterment alone seem feasible.

And selfishness lives in us not because it is ‘natural’; that is, entirely and unchangeably the product of a ‘selfish gene’ as Social Darwinism argues or because of ‘Original Sin’. It survives because it is the only option in behaviour that we have learned to allow ourselves to believe really works and which justifies other common learned cognitive biases. And what is learned can be unlearned (environmental conditions including intellectual environments allowing it and not geared to the honour of selfishness or even admission of its sad necessity in ALL interactions in the world). And whatever the social memes say, you cannot CHANGE THE WORLD by CHANGING YOURSELF and it is a red herring to try to persuade us by saying it’s better than changing the ‘ENTIRE WORLD’. :

For no-one can ever do the latter I agree. However, many models have already existed of how some change things other than just themself, even portions and parcels of the world, without having first to look after number one first and foremost. And we do not need to stop with the common instances of Mahatma Gandhi, Nelson Mandela and the haunted and persecuted seventeenth-century English Levellers. ‘Yourself’ isn’t even the best starting-place, for we are reflexive beings, continually persuaded to see the products of past human thought and activity as products of nature (even landscapes which are so not thus) and ‘selves’ which if they are our focus now are likely to remain our focus – too often as long as we live.

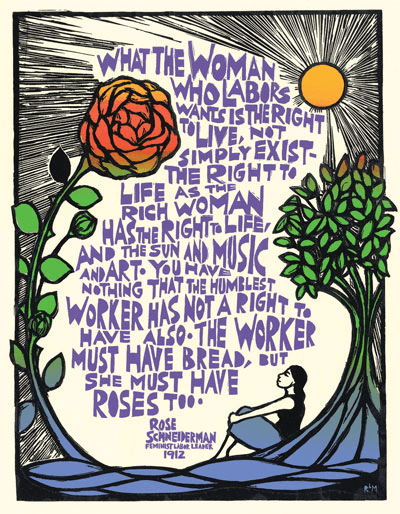

Even the term ‘yourself’ presupposes a possessive relationship – as if we owned an object not a shifting set of sensations, thoughts, and feelings somehow organised into a thing we need to believe in momentarily in different versions in order to function, even ethically. To understand that, and if you don’t read George Eliot as I do, go to the historical novels of Eric Vuillard, about which I have blogged already if you want an introduction, The War of the Poor and An Honourable Exit (each title is linked to the respective blog). And maybe the lesson is that coming from unionised female socialists in the early twentieth-century USA. For us lads (a 69-year-old queer man and still a ‘lad’) though, it is time to just stop draining that ‘udder to feed our supreme selves’. Our collective mothers can still shower on us bread and roses.

With all my love

Steven

NICE PODT ❤️💗💜🌷

Happy and blessed afternoon from Spain 🇪🇦

I hope follow my blog and GROW TOWETHER.

Greetings 👋🇪🇦🫂

LikeLike