What was your favorite subject in school?

I take my title from Henry James’ What Maisie Knew, a wondrous novel in which a little girl (Maisie of course) is exposed to the hidden facts of illicit adult sexual liaisons and the secret knowledge about adult life they normatively occult from children in the interests of their ‘innocence’. Her divorced parents and various governesses intend that this is knowledge and skill of a type that should NOT be What Maisie Knew.

One of the governesses, the gorgeously florid Mrs Wix, as poor as Maisie knows all governesses to be – presumably from reading Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and other novels – secretly prefers romantic fiction to the “subjects”, of which ‘there were so many the governess put off from week to week and that they never got to at all’ (Chapter 4). But let’s take my title citation at greater length for it concerns Mrs Beale, a woman whom Maisie’s now divorced father takes up with as a ‘good, for the child’.

It is a wonderful moment where the father hides his sexual desire for a woman in whose house Maisie’s mother thinks (though she too takes up with another man for reasons unstated TO Maisie) – and says aloud to Maisie – is one ‘which no decent woman could consent to be seen’ (Chapter 3). The quotation concerns Mrs Beale’s fancy of taking Maisie to lectures, on ‘Subjects’ of course, at what must be University College London on a street in London, whose name Maisie mispronounces as ‘Glower Street’ (it’s ‘Gower Street’ of course, but glower is apt for the true subject of these excursions not least because the College ‘glows’ for Maisie),

The institution … became, in the glow of such spirit, a thrilling place, and the walk to it from the station through Glower Street (a mispronunciation for which Mrs Beale once laughed at her little friend) a pathway literally strewn with “subjects”. Maisie imagined to pluck them as she went, though they thickened in the great grey rooms where the fountain of knowledge, in the form usually of a high voice that she took at first to be angry, plashed in the stillness of rows of faces thrust out like empty jugs. “It must do us good – it’s all so hideous,” Mrs Beale had immediately declared; manifesting a purity of resolution that made these occasions quite the most harmonious of all the many the pair had pulled together.

Chapter 17

University College London has brightened up the ‘great grey rooms’ since Mrs Beale and Maisie saw them (or as I indeed saw them as a student in the 1970s). The library, where I read this novel first though looks much as it did to me though.

I have remembered discussion of those ‘subjects’ and how they form the stuff of this novel ever since I read it at UCL in the 1970s on the course on Modern Literature. That is because James uses the word to draw on his other favourite themes – the inscrutable nature of the human as a ‘subject’ rather than an ‘object’ (and a ‘subject with an unknowable ‘subjectivity’) and as subject to (or subjected to) the power of others. Only James can play with terms in the novel as superbly as this and reading him makes this question difficult for me to answer.

‘At school’ I did not know that the term ‘subject was a construct – a name given to an artificial boundary created around an area of knowledge and imposed as a reality. Subjects divide up knowledge and skills from the other knowledge (and skills) in other domains of thought that are thought wrongly to be independent of it. Only ‘Renaissance man’ we were told in the subject called ‘History’ thought that all knowledge should be called upon in relation to a question about the value and values of human life and human activity for good or ill. Even then that bit of knowledge was only evoked to explain the comprehensive range of Leonardo’s or John Donne’s imagery (in science, geography, mathematics and so on).

Holme Valley Grammar School postcard from Huddersfiled website. Available at: https://huddersfield.exposed/archive/items/show/1838 This picture makes me remember cross-country-runs up that gruelling hill to the left.

Needless to say that very last example will hint that my favourite school subject was English but I wonder now whether that was because the teacher, on whom I had an unmistakable crush, brought out of it all that spoke to our emergent subjectivities and connected it to his – making me know what it means to feel subject to powers that appear greater than your own and independent of you, as emotions often do.

But studying literature then, under the misguided name of English, also made me acknowledge the potential richness in one’s self of what it is to be a human subject for the first time. Those conjoined understandings of my subjectness (to coin a word) I have already spoken about manifested themselves by the end of my time at Grammar School in me splurging out a thesis in in my General Studies S-level examination (they called it Special (S) level because the idea of the multidisciplinary flummoxed teachers in those days) on the subjective qualities of scientific thought and it’s social power as a thought process. The essay focused on Einstein reflecting on ripples in water and Newton on the feelings appropriate to standing on a beach and viewing the ocean; both that is reflecting on their own way on immensities. I got a Pass at Grade 1 so clearly I convinced someone that this was not just moonshine passing for thought I was delighted though to see the ripples idea used in that stupendous film starring Cillian Murphy, Oppenheimer (see my blog at this link).

My point is I think that anything that is really worth knowing needs to known and learned by being subject to everything else, for its context is not the ‘subject’ from which it derives but that very ‘everything else’ than it (however impossible that is to realise – or even imagine). To think that a ‘subject’ can, on its own, explicate all we need to know about a topic in it (such as atomic power, whilst we think of Oppenheimer) is to think artificially and narrowly. It may be to miss the point entirely. Even the word context is misleading. Nothing that exists or any question is a singular ‘text’ with a singular ‘context’ that is a ‘subject’, for everything-that-is is linked to every other thing. Granted our limitations make us make choices we call ones based on relevance but we should not equate our limited notion of relevance with how the truth of a thing in its totality is established. Moreover, we must admit to that axiomatic statement of what is the immensity and complexity of reality, whilst making the best of what we do bring into consideration pragmatically.

Now despite the fact that this all applies to the subject they call English at schools, at its best it resisted the kind of specialisation that would draw its boundaries tighter and exclude matters of human or other living interest. In contrast the subject people call the History of Art has chosen various ways of simplifying its approach, not least one supposed to favour the objective in thought. When I studied it at postgraduate level in the Open University, tutors spoke naively of essays as a means of ‘proving’ a hypothesis, as if this were a science I was engaged in. Not even science, I used to say, uses the term ‘prove’ in that way these days nor thinks of truth so simple-mindedly. Of course there are exceptions – witness Simon Schama – but their academic backgrounds are rarely ones that were in the History of Art alone. However, I am rather guiltily aware that I spend too much time hitting out at academic study of History of Art in my past blogs so I consulted the list of my past blogs to find one where I had something positive to say about how an art institution can productively work beyond the artifice of subject boundaries. I found one based on an exhibition at York Art Gallery on the art of the Bloomsbury Group (see it at the link here).

In contrast, attempts to base the learning of English at schools or universities in technical issues alone, as a higher form in fact of study of language or history (but never both together) rarely endured long. Some tried to focus it on the structure and praxis of narrative and / or genres, or the technicalities of ‘style’, or as an adjunct of historical sociology. They all failed, as did attempts to exclude translated material to give speakers in English alone knowledge and skill in contrasting approaches to a subject, its influences in other nations’ literatures or formal properties. English stood up to defend its right to extend the language out of a narrow consciousness that was based in nationalism or narrower technical approaches of other kinds. Nevertheless, idealism like that aside, I chose English, and was encouraged to do so by teachers because everyone seemed to agree that my grasp of the ‘hard: rather than ‘soft’ subjects wasn’t quite what it ought to be.

These considerations in part helped shape later life decisions for me. After a career spent teaching English to undergraduate students for 11 years, I eventually decided that I needed to study a subject in which scientific thinking and mathematics, which I had dropped at A-level, figured. Perhaps social sciences were a cop-out but I did become proficient in some uses of statistical analysis, studying it on a post-graduate module too, and, a main love now, neurobiology.

Whether I know now what Maisie knew is still not a question I can answer. However, I think her grasp of one fact is indisputable: that a fascination with ‘subjects’ is at the expense of the extension of the knowledge and skills at the complex interactive heart of our humanity and covering all that can be known ultimately. No-one can do anything other aspire to such a goal of knowledge and no doubt here as elsewhere our ‘reach must exceed our grasp’, to adapt Browning’s words.

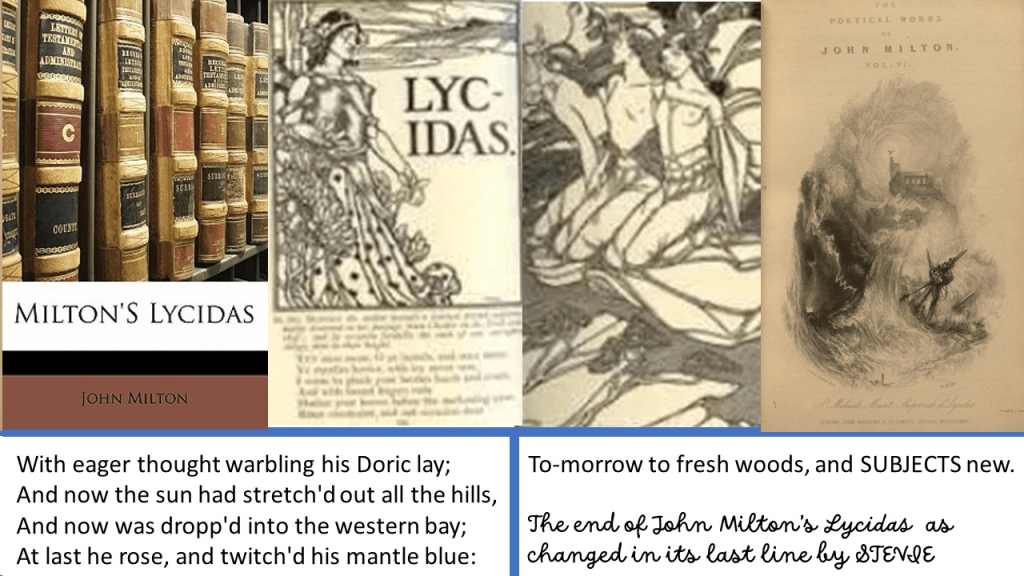

I will leave my reflections here. ‘Tomorrow to fresh woods and ‘subjects’ new’ – and no doubt I will evade those as much as I do the one above. LOL.

With love

Steven xxx