To be ‘grown up’ names, apparently at least, the end of a process of ‘growing up’ and like all ideologies buried in common terms, it assumes a teleology, in brief (though see the Wikipedia definition at the link by all means) a teleological process is defined by its outcomes and / or its purpose. If I am a ‘grown-up’ (note the shift from naming an abstract process to a proper name for a ‘thing’ that we all agree (or do we) to exist) than the process is over.

Yet we use the word ‘adult’ in common parlance quite unlike that: it is more likely that we will ask an adult to ‘grow-up’ rather than a child after all. Parents may often, no doubt, do it frequently when addressing persons they think of as adolescent and their ‘children’ simultaneously. When we ‘ask’ or demand that someone ‘GROW UP’ (depending perhaps on other kinds of relationship to them) we will often do that in anger or disdain. And, as a word, ‘adult’ (for let’s shift to that from the term ‘grown-up’ as its nearest synonym) is used variously in English-speaking cultures.

Look for instance at the Ngram below of varying frequencies in Google-books datasets of the word over time from the nineteenth, through the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries. Unreliable as such counts are (for even the corpus [the body of literature] they test is disputable as being reliable, to say the least), they make the point that as a word used in history, it is likely to respond to social, economic and ideological pressures. For instance the insistence on adult values may be more stressed in the age of the European ‘World Wars’, where the usage of ‘adult’ as a noun seems to jerk upward, for obvious reasons given the mobilisation of adults for war, but the trend nevertheless is evenly upward from the age at which legal and civic responsibilities became the sanctioned requirement for enfranchised people in a democracy or in the demand for such for all adults. That the frequency declines thereafter may have no reasonable explanation although it MAY reflect a disillusion with what adults have achieved as participants in democracy as we know it. As an adjective the trend is more steady and only takes off at the beginning of the twentieth century.

A Google Ngram adapted from books.google.com/ngrams/ and taken from from https://www.etymonline.com/word/adult. The caption there also warns that ‘Ngrams are probably unreliable’. Of course they are.

An etymological website argue that that the term itself was only very rare in usage before the seventeenth-century, and this probably reflects the fact that adult is defined in binary terms as the antonym as a ‘child’, and (according to some historians of the phenomenon since ‘the highly influential book Centuries of Childhood, published by French historian Philippe Ariès in 1960′) we spoke very little of children or even conceptualised their difference from ‘adults’ before that time, with massive changes of the concept of childhood in the nineteenth century when responsibilities for economic activity become codified for various reasons, including heightened awareness of children as ‘vulnerable’ in opposition to adults thought capable of self-defence).

As a word, ‘adult’ is often used to define values of greater invulnerability, especially to emotional influence. D.H. Lawrence used it that way often to emphasise the development of manhood in particular, with its concomitant hardening to the death of subordinate species or types (I am no fan of this man as a thinker though he writes like an angel would). I say this only to point out that being ‘grown-up’ requires submission to someone else’s values of what constitutes adulthood – such as independent self-control and behaviour and regard to duties defined by this paradigm. The key defining agency for society is of course the law and the setting of an age of majority.

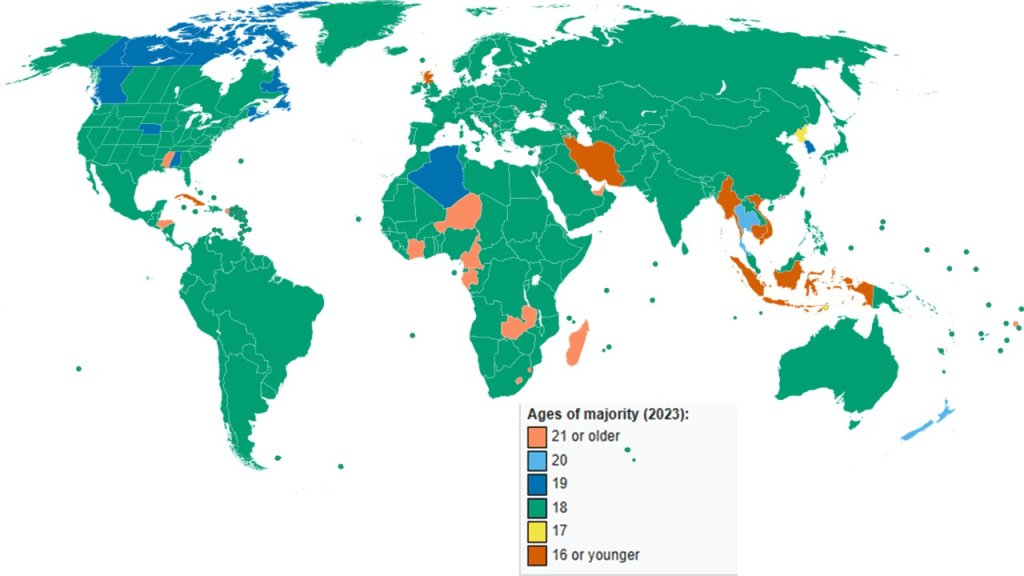

Of course, as the Wikipedia page say ‘age of majority’ is a convention set by the law of nations currently, though international law creeps in, which shows that the assumption of adult rights and responsibilities, as defined by those laws, varies by culture as well as it did in histories of those various nations and geo-cultural groupings. Wikipedia also warns that this concept should not be confused with ‘the age of maturity, age of sexual consent, marriageable age, school-leaving age, drinking age, driving age, voting age, smoking age, gambling age, etc., which each may be independent of and set at a different age from the age of majority’.

For us though this is a nice distinction for all of these age of license laws depend on the notion of an adult responsibility – that of ‘grown-ups’ – being different from those of children for reasons of social control and / or vulnerability to adult abuse. That they may differ across nations and times merely tells us that the concept of being ‘grown-up’ is delivered by the values of others that are imposed on individuals, unless they accept that their consent is presumed by a collective agreement with which they will comply and perhaps with which they are are even happy to comply.

This is the context in which I answer the question set and the context in which i need to query the use of binary distinctions like ‘growing-up’ and ‘grown-up’, child and adult. The history of thought on development, after all, soon became wary of this binary, inserting between childhood and adulthood, conceived as a state a being, a period of adolescence. This latter is a liminal period in which, despite legal definitions which must insist on a binary distinction with a cut-off point, some latitude might be given in popular or folk lore and in practice to the youth of its day.

Conceived as a period of ‘becoming’, adolescence is a kind of rite of passage (with ceremonies enough in some cultures) which admits to transition and ended only in the fulfillment of its promise, the adult. Since Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther we have thought of it as a period of ‘sturm und drang’, of rebellion like the literary movement it was named after and this has been codified somewhat in the crisis of identity confusion sanctioned in Erik Erikson’s stage theory of lifelong development, now rather unsung. That the whole theory is unsung is rather a pity since, at the very least it saw adulthood with its own series of differing development tasks and crises, rather than as the full=stop of development.

Humanistic and existential psychology is there to save us for it admits not of teleologies but of theories of emergence, where an end-product is never reached through developed towards variously and sometimes in fragments. And this is where I stand I think, as an emerging adult yet at the age of 69 on the 24th October this year (2023).

This is not to deny the concept of vulnerability of children to adult desires (financial, social and sexual) for which safeguards have so long been proven to be needed but to insist that vulnerability merely shifts its shapes and priorities through the life course and often with important social, cultural, power-based and individual variants (some huge variations in fact). The law began to address this in its formulation of legal concepts of capacity (in the Mental Capacity Act of 2005) , though in a very limited way (for good reasons).

However, in terms of the way we think of adulthood we need something stronger – a principle which does not need to vary judgments around the distinct terms child-like (considered charming) and childish (considered a fault of development or responsibility). For childhood is of course also difficult to deal with as a concept for sometimes we stress vulnerability in order to limit self-determination for no good reason or to query the sanity of children – the debate on trans rights does this all the time – and to take away their responsibility for action or lessen their rights to experimental affiliation. In adulthood too, when we stress responsibility, we too often stress simultaneously normative values quite above and beyond the limits of legal definitions (though these too, of course, interact with cultural and social norms).

Nowhere is this more prominent than in the way adults deal with the concept of play and the playful. Given licence in art and different kinds of role-play (from the educative to the privately pleasurable) we can soon turn to demand that adults ‘stop playing at (politics, family life, relationships, working for a living [take your pick]) and GROW UP’.

According to Mead and others, play is how we attain both knowledge and role self-efficacy in childhood, but long years in adult education and social work both suggest to me that this process is part of life-long emergence as a human-being (let’s drop the term adult now for this purpose). Of course, when play has a goal – as it has in narcissistic abusers of others in relationships – we can wonder if this is play or deceit, although theories of mind in human and animal development suggest these are not so distinct. For instance, a mother chimp has been observed playing at games of cooperative sharing with its baby in order to steal its food for herself, in a video I have often used in teaching but cannot find (the joys of retirement).

This phenomenon suggests to me that the important issue here is the need in human animals to stress the co-operative alongside a theory of ethics, not development. Of course responsibility varies (I am not recommending child-care proceedings against the mother monkey, whether she is typical or not) but then so does the maturation of ethical thinking in theories of moral development. Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development (see last link for information) is a fine example of how stage theories of moral reasoning, in this area as in others, can assist and limit us.

He himself would think himself a Piagetian, but moral reasoning in fact does not necessarily develop sequentially and, as a skill, both both progresses and regresses in development in both children and adults. This variation is often in accordance, and in co-variation with, the existence of environmental models of behaviour though of course I am not arguing that developmental age has no relevance.

This is clear in work with people labelled as having a learning disability or difficulty (both labels have their issues). In the folk psychology of learning disability work, the use of child models of the learning disabled person has been too long retained to the detriment of the people so labelled. It often went with and maintained a sense that this label is a diagnostically categorised illness akin to deficit of the capacity for any reasoning at all. This leads to poor child-care law decisions and poor criminal law decisions.

Social workers face such dilemmas daily. How, for instance do you respond to a thirty year old man with a learning disability, deemed to have capacity to live in semi-independent living, deciding to put known toxins in the drinks of people he does not like? This is not so straightforward an issue as you might think but the worst responses came from a learning disability psychiatrist who made it so.

Likewise if a person has a diagnosed learning disability, can they make decisions on their sex/gender at the age of 24. In the same case health care professionals felt they were not bound to communicate full truths to the service user (I say this for I have been in situations in teams where I was the only professional to believe this my duty). The issue isn’t even solved if like the USA we choose the label developmental disability over learning disability.

Hence I come back to when was the first time I felt grown-up. My answers will fit stereotypes because they are not atypical of the people of my age, class, region and sexual orientation. They are about experiments though with other people’s ideas of what made you adult – for adolescent males (and D.H. Lawrence) in my era it was often a first sexual experience or not being emotional about loss. Nowadays, I can see nothing but harm in either of these examples of ‘maturation’. There are lots of times when I first felt grown-up, all of them being will-o’-the-wisp phenomena.

In each case I had the feeling only to feel later that I must have regressed afterwards. But the feelings of achievement and regression are both fallacies based on a false binary paradigm. For a thinker who wants to see themselves as an emergent human being, the best question for me would be: ‘How do you expect to think and feel the next time you feel ‘grown-up’ and how do you predict regression from that achievement? Justify your answer with thought experiments!’.

That’s is partly a joke, but only partly.

Have a lovely day. Love ya.

Steve

Interesting

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting post

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well written, keep going ✍️

LikeLiked by 1 person