Reactions to performances of The Merchant of Venice 1936 seen at Theatre 1, HOME on Thursday 16th March 2023 2.00 p.m. in Manchester and Othello by RSC Livestreaming on Thursday 23rd February 2023. Catching up with ‘The Elephants in the Room’.

An update of the blog at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/12/the-elephants-in-the-room-racism-in-the-british-artistic-heritage-this-blog-written-to-prepare-me-to-see-new-productions-of-othello-national-theatre-live-str/

This is a catch up on an older blog needs that dealt with what I expected from the two plays mentioned in my title. However, I do not in what follows give much update on the National Theatre’s Othello, for though the production satisfied in every which way, it satisfied in ways that I think I predicted in the earlier blog, if not more so!

What was certain was that this live-streamed production had been undersold by even the reviews I cited, to say nothing of the rest that I did not cite. Most of all, it was really useful to see the discussion piece by the director and various other critics and academics played in the interval of the live streaming. That is because these participants made it clear, as reviewers in the newspapers did not, that the production intended to give a consistent reading of how the emphasis on feminist and anti-misogyny themes (innovatively and brilliantly played forward by the white actors taking the roles of Desdemona and, Emilia as mentioned in all reviews) intersected with the more obvious themes concerning racism in action. For intersection of both themes cuts down the margin too intersecting both manifest forms of these social oppressions and the self-oppression of the characters on whom manifest oppressions impact the most. That Desdemona was the victim of both misogyny and racism has never been a point made more clearly, yet the reviews I cited often pitted admiration for this production’s feminism against a white-privileged view of what it did with racism, in the treatment for instance of the actor playing Othello himself. Indeed, the production made it equally clear that the racism inflicted on Othello came in part from his own introjected versions of it.

Though I have seen some enacted Othellos that were excellent, and some, like Laurence Olivier’s that were far from excellent and extremely racist, I have never seen such a finely nuanced Othello that dealt with the preoccupation of the character to fit into the hole dug for him by a white state. He does so even down to the extremes of becoming the military macho ‘hard’ man (the very opposite of female gender stereotypes), supposed to be provided best by Black men who can be persuaded unwittingly to believe they are insensitive to the finer things enjoyed by white people of equal status who serve the white court or other white status quo:

… Haply, for I am black

And have not those soft parts of conversation

That chamberers have, …[1]

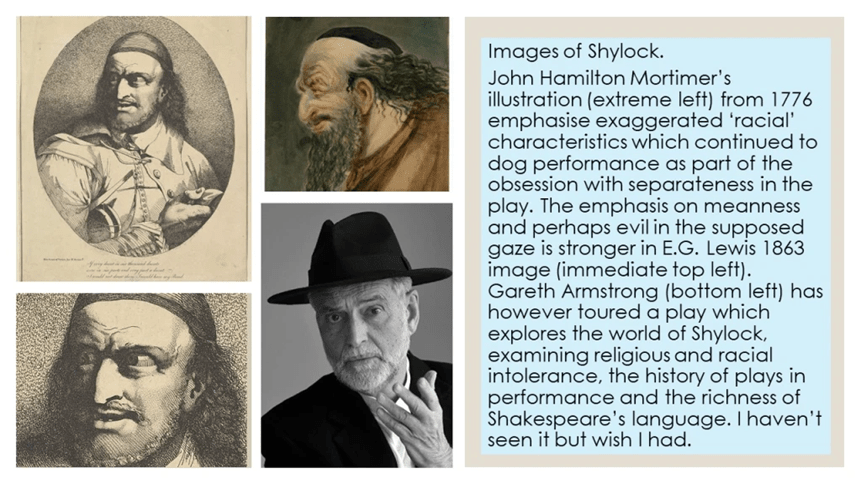

In the end, as the director said in the discussion, the use of chorus, much like those of ancient Greek tragedy allowed negotiation between inner and outer worlds for a chorus of this kind can access both – in the form of inner drives and effects as well as external ones. So I can only recommend you see this production when it is released again in cinemas or by purchase on home streaming options. However about The Merchant of Venice 1936, I want to be more specific in praising the production, particularly the role in it of Tracy-Ann Oberman, not just as a fine Shylock, the best I have ever seen, but for a brilliant conception of Shakespeare’s play that finds in it how it can be read as a work that, whilst it inevitably, for its period, proposes and plays out a stereotype of the Jewish person, also addresses the processes of anti-Semitism in an urgent way. Again my mind has been made up, and my ideas changed from what they were in an earlier blog by Justin Curley, my best friend, who with his sister, Naomi, saw the play with me.[2]

For Naomi, Justin, and me though the circumstances of seeing the play are also worth describing. We had booked seats that were advertised as ‘on the stage’. And indeed they were. Theatre 1 at Home is a modern stage but uses a conventional proscenium structure, though a raised platform was added that jutted into the auditorium from the proscenium stage and at the same level. Along each wing of the proscenium stage there were three tables, each with three wooden seats. It was at one of these we sat – the diagram below provides a sense of both our seated position and the look of the stage and auditorium of Manchester HOME’s Theatre 1.

Theatre staff forewarned the nine people who had booked stage seats, what to expect. At each table were small glasses containing a small amount of dark grape-juice, imitative if alcohol, to be drunk by us when a stage actor proposes a toast at a Shabbat blessing. We were to stay within lines drawn on the stage to facilitate exits and entrances around our seats by the cast and told that at the end of the second and final section of the play’s production there would be a staged ‘political demonstration’ in which we were invited, without pressure, to take part.

The play was set in 1936 in London on Cable Street and against the backdrop footage of the 1936 march was played as and when appropriate. The programme gave details of the ‘Battle of Cable Street’: a demonstration planned by the British Union of Fascists (to become in 1936 the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists) under [Sir] – only the British could thus honour a Fascist – Oswald Mosley.

Antisemitic Cable Street material from the programme and a copy leaflet handed out to stage ‘audience’ by actors playing Blackshirt militants.

The Cable Street Fascist paramilitary demonstration was the more provocative (and here a fact I did not know before) because it was meant to avenge a failed demonstration at Holbeck Moor in Leeds that had preceded it, but which had been foiled by the local community. Hence, in Cable Street another local community – formed by alliance between populations that were Jewish, Catholic, Protestant and atheist, including of course prominent Communists – was being mobilised to counter what would be a very significant show of right wing force supported by prominent and aristocratic patrons. This context was reproduced in the production by casting the Christian group around the merchant Antonio – after the first few scenes, and including the Duke of Venice – as Fascists wearing black (Mosley’s people were called ‘Blackshirts’) and an arm band each resembling that of the SS. Those costumes became increasingly more evident. Portia’s home at Belmont, though distinguished from the Cable Street scenes which were backed by red-brick simple housing including a pawnbroker’s symbol over what would be revealed as Shylock’s home and business place in the ‘ghetto’ of the original play.

The context of moneylending and its association to the Jewish population is a well-worn theme, based largely on the resistance of the medieval Church (not as steadfast as it was boasted) to usury (or the lending of money at interest so that money ‘breeds’ money, although often used only of exceptionally high or ‘unfair’ rates of interest) even as mercantile capitalism advanced making the flow of capital from borrowed sources a necessity for economic gain. This is the rational used by Antonio and other Christians for despising Shylock, who says to the former:

Signior Antonio, many a time and oft

In the Rialto you have rated me

About my moneys and my usances.[3]

Antonio’s reply make the classic Christian complaint against usury, or ‘usances’, that it ‘takes / A breed for barren metal’. Yet Antonio escapes the same castigation though his money gains are, as the play shows, entirely speculative. These associations this production makes clear, although with a clearer sense of the hypocrisy of a mercantile class thus demonising Jews for doing much the same with their stored capital. In looking at the history of the resistance from Christians to moneylending by Jews, this production like others explores the world of Jewish moneylenders (in fact a much smaller world than that imagined by Christian critics, for Rebecca Abrams says that in ‘medieval England’ only around 1% of Jews in England engaged in moneylending). But this production takes the exploration a step further since the one-page article just quoted on the subject in the production’s programme by the Jewish feminist historian, Abrams, concentrates on ‘Female Jewish Moneylenders’, who were not represented in literature by authors from the Christian world.[4] This piece details examples of such a moneylender, Licoricia of Winchester, from the thirteenth century who was ‘on occasion forced to forfeit her bonds, and imprisoned at least three times in the Tower of London’ and in ‘1277 stabbed to death in her own home’. Such women have been erased from history, Abrams says. Onto this model Oberman cast the image of her own great grandmother, a refugee from pogroms which depopulated Belarussian shtetls, who a widow, was:

“a tough single mother in London’s East End. She lived in two rooms in a tenement flat near Cable Street until she was 98”. … “… The very thing that made them survivors also made them outsiders – too loud, too brash, too strong, too opinionated”.[5]

As in the Othello production then, antisemitic racism, and indeed racism more widely, is explored in its intersection with anti-misogynist feminism, which fits Shylock well, though never before thus experimentally explored. After all there is much in this play about gender that contrasts male privilege with female subjection of one kind or another. Jessica dresses as a boy to escape Shylock and go out into the street shamelessly:

For I am much ashamed of my exchange.

……, Cupid himself would blush

To see me thus transformèd to a boy.[6]

Portia and Nerissa dress as young men to stand as legal counsel for Antonio, making their husbands think them ‘accomplished with that we lack’ (it is an ironic play on sexist ideology that allows Portia to equate knowledge of the law with having a penis whilst undermining that ideology at the same time).

… but in such a habit

That they shall think we are accomplishèd

With that we lack. …[7]

Oberman has insisted that when Shylock is a woman, it is easier to see her as neither of the stereotypes of the Jew used most persistently in past productions. She says, again to David Jays; ”I’ve seen productions where Shylock is mocked. I’ve seen versions where he’s a complete victim. I don’t know which is worse”.[8] To be a grasping stereotype so extreme you are comic or a ‘victim’ without any sense of agency for one’s own survival live on in the ways the Christian cast would like to see Shylock are poor alternatives for a Jewish person acting another Jewish person. This is why Oberman’s Shylock stayed on stage after her humiliation in Christian eyes to help lead the Battle of Cable Street – political hero rather than victim. It is also why her skills an actor draws out nuances of sensitivity in the character, while not playing down the reactive vengeful malice and cupidity of the stereotype that cruel life experience has enforced on the otherwise excluded from the ‘means whereby’ one can ‘live’.

…..; you take my life

When you do take the means whereby I live.[9]

Thus you though the play cannot escape the fact that the cultural stereotype of the Jew exists in non-Jewish eyes to be mocked, you can allow the production not to collude by reinforcing the racism of the non-Jewish characters, and not just their anti-Semitism. You can more thoroughly hate Portia’s complicity with the entitlement of the white rich when she acts as this one does to emphasise her disdain for one of her suitors merely because he is ‘black’. To dress them in Fascist costume, underlines their complicity and not only collusion with irrational hatred of the other they create. After all Shylock exists in part so that Western Christian characters can continue to project into another their own confusion of the value system of love with monetary value – evident in Belmont luxury, avaricious global trading, and investment, as with Bassanio, of other people’s money in one’s own marriage prospects, so ’fortunately’ aligned with fortune-hunting. Hence Solanio, an also-ran Christian, dressed in this production in Blackshirt uniformity represents and enacts Shylock:

I never heard a passion so confused,

So strange, outrageous, and so variable

As the dog Jew did utter in the streets.

“My daughter, O my ducats, O my daughter!

Fled with a Christian! O my Christian ducats!

Justice, the law, my ducats, and my daughter,

A sealèd bag, two sealèd bags of ducats,

Of double ducats, stol’n from me by my daughter,

And jewels—two stones, two rich and precious stones—

Stol’n by my daughter! …”[10]

When Shakespeare shows Shylock reproducing this kind if incident, there is room for the nuance though oft played as a mere ‘showing’ of Solanio’s later ‘telling’ of the scene. Played as Oberman played it, it showed that Shylock is not merely reductive of the love of his daughter so that love equates with the commodity’s exchange value but speaks of value accrued by association with past emotional rather than monetary riches, that have got, as does all psychological truth, entangled between emotional and physical representation of worth: ‘Thou torturest me, Tubal. It was my turquoise! I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor’.[11]

Survival may involve confusions of the ‘means whereby I live’ with other life values, but it does so only in socio-economic circumstances, like those created by racism not of one’s own making, whatever one’s agency as a person. Only the rich and privileged manipulate value and can still make it look like an exemplum of their idealism – which is Portia’s truth exactly, and even more evidently Antonio and Bassanio’s truth – for they barter love throughout, as Portia knows and makes evident to them in her play with the exchange of rings.

At the end of the play sitting where we were allowed, as staged audience, to take part in the representation of Cable Street. Justin helped build out of chairs from our tables a barricade against imagined oncoming Fascists. Naomi and I were invited by actors behind the brave banner supposed to keep out Fascists and to raise our left arms shouting that notable phrase, ‘They Shall Not Pass’. It’s a game, a play, I know but I felt proud to be associated again with the anti-Fascist tradition as I was in my youth. It was a wonderful afternoon. Thank you Tracy-Ann Oberman and the creative team. This was a Merchant of Venice to redeem others.

See it. It is going to Stratford, as it should.

Love

Steve

[1] William Shakespeare Othello (III, iii, 304ff) Available in full text: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/othello/entire-play/

[2] For earlier blog, since I have to come clean, see: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/02/10/visiting-manchester-a-preview-of-the-highlights-on-my-visit-to-justin-from-monday-15th-17th-march-2023-its-gonna-be-a-blast/

[3] William Shakespeare The Merchant of Venice I, iii, 116ff. As in online text available at: https://shakespeare.folger.edu/shakespeares-works/the-merchant-of-venice/entire-play/

[4] Rebecca Abrams (2023: 4) ‘Female Jewish Moneylenders’ in HOME / Watford Palace Theatre Programme for The Merchant of Venice 1936, page 4.

[5] Tracy-Ann Oberman interview cited by David Jays (2023: 8) in ‘After playing Shylock, I would have a sense of shame’ in The Guardian: G2 (Thursday 23 February 2023) pages 8f.

[6] The Merchant of Venice: op.cit. II, vi, 36ff..

[7] Ibid: III, iv, 63ff.

[8] Cited David Jays op.cit: 8.

[9] Ibid: IV, I, 392f.

[10] Ibid: II, viii, 12ff.

[11] Ibid: III, I, 119ff.

Love this Stevsn x

LikeLike