A blog: Steven the ballet virgin visits Birmingham Royal Ballet performing Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake at the Sunderland Empire on the 10th of March 2023, 2.00 p.m. performance.

Once, long ago my husband Geoff and me visited the Soviet Union (it existed then) on a gruelling but wonderful Intourist programme seeing Moscow and what was then Leningrad. I think we saw, amongst the sights the group were herded into, a ballet called Don Quixote in Moscow but memory of it has paled in contrast with seeing Cossack dancers on the evening after; I have no memories of it except for the magnificent theatre in central Moscow, but even the name of that theatre I forget. Hence I see myself as virgin to ballet, and I had no expectations if not a little dread. On the morning of the visit unseasonal snow lay deeply and I almost rejoiced I could not go, although I didn’t give that away when I tweeted that morning.

Fortunately, I had arranged to drive there with dear friend Linda Goffee. I found her enthusiasm undiminished and the snow seemed to ease faster than expected in brave March sun, so we went. I could not have been more pleased. It was an experiment, and we couldn’t afford more than the subsidised £13 seats in the Upper Circle and I wondered if that would spoil the view. It really didn’t – one saw, as it were, the whole performance sculpting the entire three dimensional space of that magnificent stage – though I could not predict even at the opening that this was how I would experience the whole afternoon.

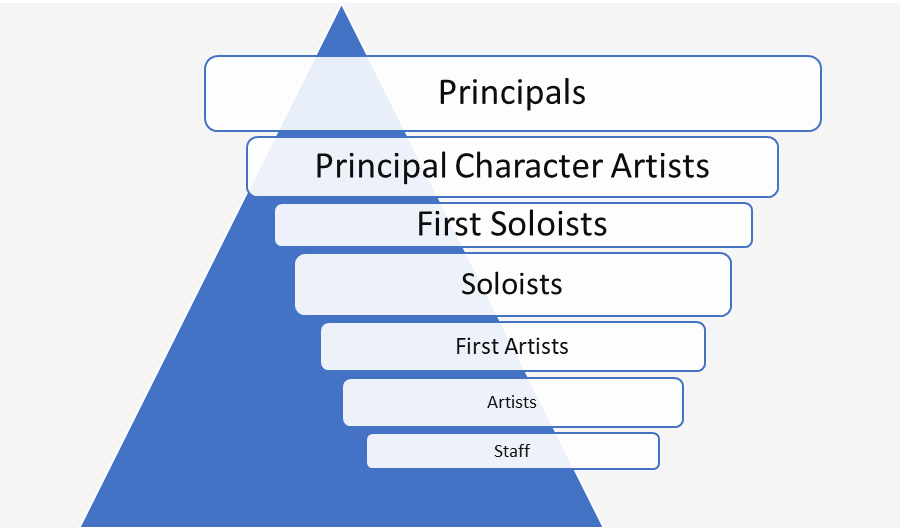

I looked through the programme and, in many ways, was put off by the culture of ballet displayed therein, though it was great to read up the story to be enfolded I read that story at first only in the children’s graphic story version, which missed out the emotional nuance. As for the purpose of the programme booklet, I wanted to know who played whom in that story but the ballet ensemble was introduced in that book only through its members in an established hierarchical arrangement:

None of this augured well to my rebellious democratic socialist soul which kept shouting at me: this is an elitist aesthetic artform moulded by aristocracies and reproducing notions of aristocracy (however difficult it may actually be to win merit in ballet and it clearly is). The potted history of the ballet in the programme showed it to be a form, when Tchaikovsky himself ventured into it to ‘try [his] hand at this kind of music’, subservient to the aesthetic whims of potentially ‘indifferent’ choreographers all too ready to serve the egos of ‘star’ performers for a more commanding role, even at the cost of harder work for those ‘stars’, Noël Goodwin shows in this rather good short essay in the programme. For instance Anna Sobeshchanskaya inserted a pas de deux to show off her skills using music inserted by Marius Petipa (the composer of Don Quixote incidentally) into Tchaikovsky’s score. Goodwin blames these lightweights for ruining Tchaikovsky’s more holistic conception of his debut ballet, running, as it did, till everyone (including the sets) got tired and faded and the ballet faded from history. After all, the Petipa-Ivanov original choreography (still used as the ballet’s basis) had highlighted the role of the star performer playing both Odette (the white swan/princess) and Odile (the black swan/princess and an apparent simulacrum of Odette) by inserting 32 fouettés (turns on one leg propelled by the extended raised leg – almost Herculean in muscular difficulty no doubt) into the story in Act III for its chief female star.

To be frank there were elements of ballet culture, even after the end of a production with which I was enthralled, that I was less keen on. The ballet itself contains many set pieces, including dances by each of the three princesses amongst whom Prince Siegfried, much against his melancholic and rather narcissistic wish, must choose his bride. That at the end of each dance – lively in itself – the audience must clap for this is in fact seemed the intention both of the of character played (dancing for a queenly role after all) as well as the dancer who is its present avatar. This treatment of each dance as a showpiece is, it seemed to me seeing for the first time but having noted the same in opera, is how audiences act in ballet performance; apparently well-trained and holding up the action of the whole dramatic storyline and the ensemble effects by clapping the set pieces of the ‘first soloists’ and ‘soloists’ for their singular achievement. Now it may seem churlish to dislike giving homage to great singular performance, but it seemed to me to so scripted a behaviour (for audience and cast) and thus more to do with deep (and unconscious) culture than appropriate response to the artwork itself. Of course these distinctions sit on sticky ground, especially from a self-admitted ballet ignoramus. When I voiced these doubts to Linda (amidst much effusive delight otherwise for the performance) a rather rude lady sitting in front of me put down her glass of wine and took her hand from her popcorn to expostulate against me for being insensitive to the hard work being done by each dancer, worthy (she thought) of the clap they richly deserved. Well I never. At least that made one f the 20 minute breaks more bearable and fun. I do regret seeming to be insensitive to talent in individuals though for I don’t believe I am.

To be honest, these thoughts and emotions were such minor motions of my brain that they were dwarfed by love of what I saw on the stage, for here, I thought, was an artform I could see as an extension of other things I love – a form that turned figure sculpture into something living in time, made dynamic by story. Ballet is obviously about the body, I suppose: not just the individual body, though that makes incredibly complex forms, but the whole body of the ballet company – hence rightly known as corps de ballet – a social body which moves in three-dimensional highly sculpted motion. In Swan Lake the corps de ballet is a star in its own right, notably of course, but not only, in the role of the whole body of swans in Act II, but especially in Act IV, where words fail to describe the effects, but which start with the whole avian social body rising through the dry ice enacting lake-level mist at its start.

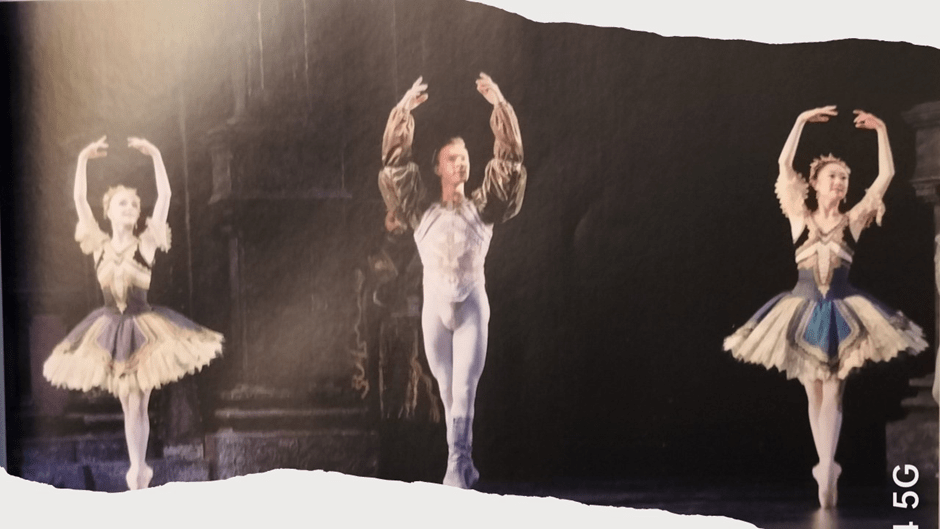

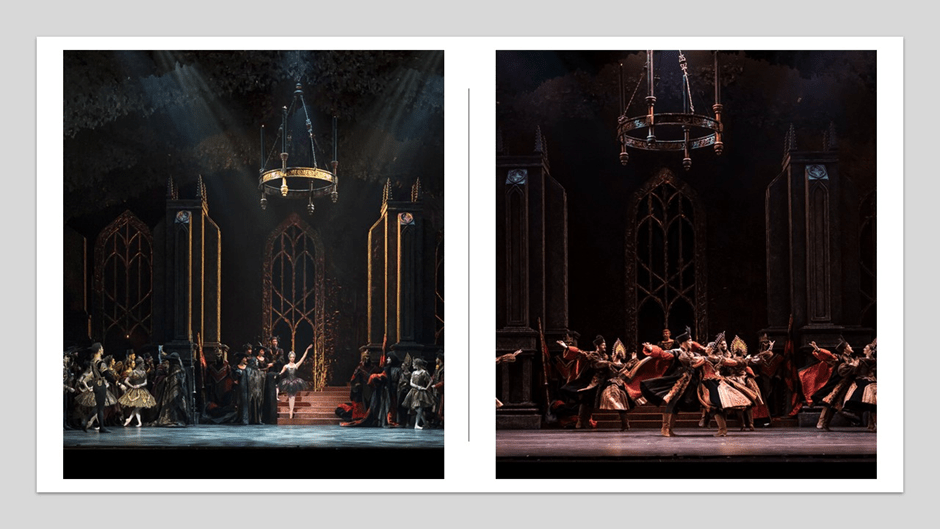

In Act II and IV the ballet body’s soloists, as we see above, individually, or in synchrony when two or more dancers, make fabulous shapes even out of three dimensional, and apparent empty, air-space. Space itself, in all its dimensions, seems to co-operates in the shaping of patterns. Meanwhile, the larger social body takes sometimes static identical form, using a stance of apparently unnatural ungainliness (as seen above) – but yet truly beautiful in its spatial rhythm in the whole social body. The whole shaped line of this corps de ballet forms a background for the space they define. In this space principals, soloists or a smaller distinct group perform their exquisite, differentiated dances. The whole of each body is mirrored in the body of others that make vertical and lateral shapes using the depth, height, and width of the stage. Sometimes the corps dividing itself to form ever more exquisite coming togethers or even graceful exeunts (stage left or right). Avian form is suggestive in this ballet of ways of handling these moments proper to the art form hence the wonder of Acts II and IV. However, the courtly settings of Acts I and III also provide analogous uses of individual and social bodies in three-dimensional space.

In the Court scenes in those Acts, differentiated groups meet together on stage as demanded by the story. Fine effects are found in these social encounters. When, for instance, the hosting court and its members invites visiting courts – those of the three suitor princesses for Prince Siegfried – each court represents itself in dances so different, in size, patterning and predominant technique from each other and the social body around the edge of the stage again take on the role of defining space for the visitors to perform. Costumes seem designed to move so flexibly to help in forming the dynamic pattern-making on stage and this may be a reason for their extraordinary weight as mentioned in the programme. The courtly corps of the court of Siegfried and his dowager mother also, like the swans, have distinct entrances and exeunts, but the richness of colour in these scenes is mirrored in the richness of choreographic variety. Groups form singular patterns – to speak their social and/or individual character. Even in the neglected Act I, which I loved, the play between the solitary Prince Siegfried is shown as in subdued mood by the obvious contrasts – in costume and movement style – of his equerry, Benno, whose beauty leads groups of followers male and female to try and energise the solipsistic Prince in the wake of his father’s death (very Hamlet-like in that).

In the picture above the shaping of vertical space in curves, lines and spirals in each body allows for contrast even in the similar poses created by gender and gendered costume, though of course in a conventional binary hierarchy. In Act III, when the visiting courts dance, they manifest different cultural forms (even though they seem markedly stereotyped as they should for the uses of a power-hungry Russian Imperial Court). Each court’s dance – the first females patterned around lead males, the second in patterns formed by equal male-female couples and the final one a triumph of sparkle between four dancers – is followed by the dancing of the princess to meet the prince’s eye. They seemed much of a muchness these three female solo dances (though brilliant of course) as if illustrating that, whichever princess he chose (and however the exciting difference of their background cultures) he would receive much the same package from each, unlike that offered by the avian-human difference in Odette (so cunningly imitated in this Act by Odile). Here dance and dancers serve narrative and character including that articulated in the music. Here, I think, possibly lies some of the glory I sensed would lie in ballet proper, outside the ‘star’ system.

Pictures fail to convey that of course but it is noticeable even above how social bodies dwarf the impact of even stately background sets and settings for they are, as they are never in drama or opera, truly only background, often displaced by shapings of dance space made by the surrounding corps de ballet. For all that, what enthralls is the way a ballet’s plot or story, of whatever apparent lack of nuance or fairy-tale simplicity, is often given psychological depth by collaboratively shaped artistry, and in that ballet defies its own socio-cultural background (born and thriving mainly in the privileged amongst hierarchical and even rigid societies. For instance, playing both Odile and Odette mist have immense challenges for a female principal. In the programme, one principal who plays this role, Miki Mizutani, says she felt her strongest challenge in enacting the difference in dance mode between Odette (‘pure and delicate, strong but also sensitive’ she calls her) and Odile (’very confident and … deceitful’ again in Miki’s words). She internalises the rationale of that difference as being that between what it would mean to dance each role respectively as ‘a swan’ (for Odette) and (for Odile obviously) ‘a human imitating a swan’.

When I first read that comment, I was not that empathetic to it but on reflection I now think that, from the point of view of an artist, it is superb. For here the artist must (as I think the music does with its darker version in Act III of the Swan theme from the end of Act I and the beginning of Act II) understand how to imitate in ways that disguise imitation for Odette and to emphasise her cunning art as Odile. Hence perhaps the necessity for both character and plot of the 32 fouettés danced by Odile in Act III under the eye of her evil magician father (a bad Prospero indeed). Perhaps for Tchaikovsky the whole was ideally a reflection on how concepts of nature and artifice meet in an ideal form whilst being unable to disguise in the end the contradiction on which art is based. In that he would not be unlike Pushkin. For even to bad ends, the art of an Odile is exciting, but especially if you know the dancer of her role is readying herself for the ‘masterpiece’ (in principal dancer Brandon Lawrence’s evaluation in the programme) of Act IV as Odette in which nature asserts its superiority to clever artifice and magic, but, as it were artfully and magically.

Thank you then Linda, Sunderland Empire and Birmingham Royal Ballet for this revelation of an afternoon. This is the start of a new love.

Love

Steve

I have wanted to see this ballet forever, thank you for sharing this. I am a big fan of Tchaikovsky and love Swan Lake, having only listened to it on audio. I love how you include this description of what ballet is as an art form

“a social body which moves in three-dimensional highly sculpted motion. ”

I had no idea about the illusions to sculpture rooted in ballets dancing bodies. Thank you for sharing this.

LikeLike

Brilliant review, a joy t0 read thank you

LikeLike