My head is in a shed after seeing Northern Rascals play out their wondrous multi-genre and multidisciplinary art form in their current touring production that ended in Bishop Auckland Town Hall last night (Wednesday 19th March 2025). But what a wonderful gift to every sense and to the co-interpretation it invited between audience and the Northern Rascals crew was this unassumingly staged SHED (until it began playing).

Dance is an art that is, in all its forms, about the distance and proximity of parts of the body operating outside norms set by its psychosocial regulation in everyday life, even when a dancer dances alone. The term corps de ballet (the body of dancers in ballet who form the ensemble of non-principals) in productions in classic ballet evoke the idea of a single body, although that social body acts in regular, and often highly regulated subordination to the singular bodies of the principal dancers with each other. The extremes of encoded formalism in the technique of ballet shows how extremely and ‘unnaturally’ complex have to be the coordination of movement in the performance of principals and corps de ballet in order to tell a simplified story, such as that of Swan Lake (see my blog on my first visits to that story at these links, both in the forms offered by the Birmingham National Ballet and Matthew Bourne’s more radical version). In the first in particular, I pressed the analogy with sculpture but of sculpture in which the dimension of time is also sculpted.

Modern dance still uses a repertoire of repeated body movement distortions, but no longer subordinates them to a simple reading – the meanings emergent from them, even if only those of an aesthetic motivation ready to take on board notions of the fragmentation of supposed wholeness and unity, including shifts between forms, and what might appear to be formlessness, are less bendable to a simplified psychology and psychosociology. And this is more the case if storytelling in dance is cut off from simple fable and fairy tale. Hoffman’s complex story of psychosocial fragmentation in The Sandman is almost monstrously distorted back to norms in order to become the ballet that is Léo Delibes ‘Coppélia’ (as satisfying as the latter is in productions with high skill in their stage production in evidence). I almost hint at that in my blog on that ballet. For when I saw the production done by the English National youth ballet, offering an outing to local children as the ‘corps de ballet, it was an awful experience, except for the Mums and Dads of said infants. These ballets are not only simplified but also rely (except of course in the case of Matthew Bourne productions) on an unhealthy relationship between a standard telling of the story in the programme published for productions on which any attempt at narrative understanding comes to rely.

Hence, seeing Northern Rascals is a jolt. Northern Rascals #, by the way, is a nationally recognised performance company and is led by Anna Holmes, who always writes their playscripts, and Sam Ford. The company provide a simplified version of the stories in their production of Shed on their website, just as a conventional ballet might, but it suggests more than openly shares with prospective theatregoers and is not, in my view, the kind of necessary aid required by classical ballet-goers. Here is their version of the story; in case you don’t want to turn to the website itself):

Performed inside an intimate, pop-up set that feels like peering into someone’s flat, SHED offers a raw, authentic, and uplifting experience. Featuring three short stories:

Sunny Side

A poignant exploration of adolescence and identity, Sunny Side follows K as he navigates a world on pause, grappling with a loss of emotional and physical connection. Caught between past, present, and future, K’s journey reflects the struggle to make sense of life’s changes.A Small Life Just Like Mine

A modern day love story. A Small Life Just Like Mine tells the tender story of two lovers navigating the seasons of their relationship. Amidst the mundane and messy realities of partnership, the beauty of connection shines through.Blackcurrant Lips

At the end of a night overshadowed by threat, two friends reflect on female safety, power, and the realities of being a young woman today.Northern Rascals bring a fresh perspective to dance-theatre; a portrait of love and loss and the essential humanity that resides in us all.[1]

Here is the story however, as the reviewer for Yorkshire Bylines, Will Wrighton (in a sensitive review full of appropriate praise for the company) saw it:

The first story tackles friendship between two friends and, while one of them goes off to university and makes strides in their life, the other has a sense of loneliness and feels like he is lost. The second story shows the struggles that come with love. The brilliantly entangled dancing between the couple displays how one minute you can be in sync with one another and the next it’s awkward and painful. / Finally, the third story is about the misogyny that women face and the effect it has had on these two friends all of their lives.[2]

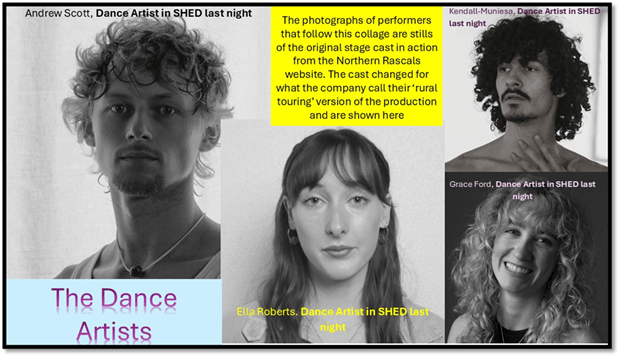

In some ways Wrighton’s retelling merely shadows that on the company’s website, but it felt (to me at least) somehow out of key and tone as a description of the actual production (in a way the company’s own descriptors do not) because of the manner in which Wrighton reserves the description of ‘love’ as the basis of story only to the second narrative of the three, where the lovers are heteronormatively heterosexual. The second story is beautiful, of course: both beautifully danced (between Andrew Scott and Ella Roberts in this touring version) but working best when seen as part of a triptych where, as the Northern Rascals descriptor may suggest (whilst not making that meaning entirely explicit) ‘love and loss’ form the entirety of the connection of the three stories. For love and loss are not experienced only within heteronormative encounters and narratives.

Of course, I do not mean by that that there is anything like a simple binary (queer and straight) operating in the gaps between these stories – wherein we see a gay male and a lesbian experience flanking the heteronormative one. The show does not work so simply or with that absence of assumed nuance in the meaning of relationships. Though the males in the first story (Cato Kendall-Muniesa and Andrew Scott) may be merely provincial friends and room-mates – perhaps – and the females (Ella Roberts and Grace Ford) in the third are childhood friends meeting up and remembering they once both had chubby cheeks and ‘blueberry lips’ from sharing an ice lolly , and were girls together linked in what we ought to call ‘love’ too (the infant girls appear in video – projected onto the set and the continuing dance of the two adult women against the set). Nevertheless, the matter of ‘love and loss’ definitely applies to them too, whether they recognise romantic and or embodied relationship between themselves or not in that which their bodily play of proximity and distance in the codes of dance represents in ‘real life’.

Andrew Scott, Ella Roberts. Cato Kendall-Muniesa, Grace Ford, Dance Artists in SHED last night (Norther Rascals website black & white photographs: https://www.northernrascals.com/shed)

In working out how story-telling works in this bold innovative trans-generic theatre form, I have to say that Will Wrighton is as right-on as his name suggests. He wants to see the success of this production in its cast at some points but his description also shows their excellence elsewhere than in the visible cast too. Indeed, he saw a different cast from that in this touring production. He saw Grace Ford (who is the only survivor from the original to the touring company), Flora Grant, Theo Arran and Soul Roberts. What he says, however, applies equally, at least to the touring cast too, as if some higher principle than casting was at work across this production. And there is such a ‘higher principle’ which must derived from the collaboration of all the elements available to this company. Wrighton describes Northern Rascals as ‘a multi-disciplinary performance company based here in Yorkshire. Its mission is to create art using dance and theatre, inspired and driven by social conscience, placing original storytelling into the current socio-political climate’. He goes on to say particularly of the production that, words that show that the meaning of multi-disciplinary does not refer to only theatre and dance:

SHED uses digital art, spoken word and contemporary dance to raise awareness of the issues young people face with mental health. … / …. The clever writing by Anna Holmes gives a great tone to the trio of stories and had me thinking about my own experiences with loneliness and love./…/ The set itself, while simple in its appearance, is great …. My favourite part of the set was the digital art that also tied into the show itself. I think the way shapes, colours, people and words are shown also helped display what each story was trying to tell and set the mood.[3]

I cannot improve the range of issues which add up to the multi-disciplinarity of the production given by Wrighton but I do feel that he may undersell their effect, even given the beauty of his manner of sharing how much he identified with the themes of ‘loneliness and love’. I only say this because you may imagine the mix of disciplines in the production as a whole was only a means of enhancing the ‘display’ and set the emotional mood of the story. These techniques are used much more interestingly than they would be if just techniques of enhancing theatrical effect, for in some ways they set theatre against other genres – digital video, word-processing, display and fading, dynamic pattern projections and colour washing. Even very sophisticated that uses such techniques do not do so to the same effect as this show.

At times our response as an audience works across different genres and modes of their delivery. The very fact that the dancing cast do not voice the script matters. There is no attempt to create even the illusion that it is they speaking and not voices caught on a recording made elsewhere. Wrighton names the voice-actors who dub the dancers speech as ‘Lamin Touray, Brendan Barclay and Anna Holmes’, but it is only one element in which the story fragments across the genres it which it is multiply told. Sometimes this prose – in description and dialogue, but at other times it is in the most intense poetry that emerges – often with intended time-lapse, between textual and spoken versions of the poem. The text is cast onto the set.

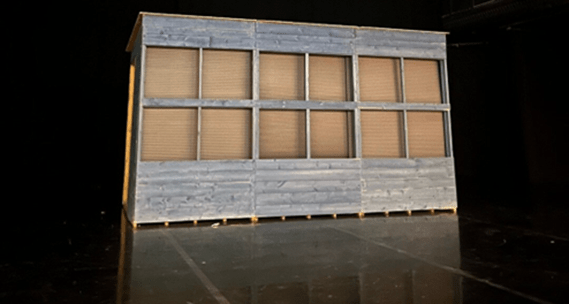

Let’s take the set (designed by Tabitha Grove), which, unlike Wrighton, I prefer to think of as the focus of visual, textual and audio-sculpture. This is, by the way, what the set looks like as you enter the theatrical space, before you see what lies within what the blinds hide behind them:

Even when moving two-dimensional figures are projected on it, they look three-dimensional because the relief of the ‘shed’ wall (the set) is three dimensional – a wooden frame – blue in natural light, but not always in such light so transitioning constantly – with gridded squares that acts variously as ‘glass’ windows through we see into an interior (of a room of differing kinds), or portals between the imagined interior and exterior space. Blinds are pulled down across the open spaces on that can be pulled fully to make a blank if uneven space or projection (with three dimensional characteristics when the whole is used. They can be pulled down partially to isolate some spaces. In the second act story. The left and right panels are made to represent the two isolated flats in which each ‘lover’ lives until they form a romantic and sexual relationship.

Moreover each space can be used so that it acts as a singular screen on which one image plays as if on a TV screen. Or an image can use them as if the image were that seen through a two-pane sash window or one with four parts. In part that allows the scenes indicated to vary.

Transformed by light art – both used to shape and colour (by Kieron Johnson) – the figures projected on it can seem to be emergent from the interior hidden behind it as a screen. The videographer (Genevieve Reeves) merges her art with that light patterning and projected digital effects (by Aaron Howell) . Similarly the projected text of the script, especially when it is also the text of poetry that is not synchronised to it, but if so patterned unconventionally across the projection space (with or without the blinds up or down – the combinations are endless) such that even the poetry is recalled over different dimensions, including shifting time lapses. Sometimes the dancer’s body itself breaks the illusion of window glass, attempting to own themselves as both an inside and outside.

Some of the keywords of the poems is often projected before and after its main appearance in the form of a textual collage. In such a work, it is impossible to see what of the work was given to sole responsibility of the producer (Callum Holt), the Dramaturg (Geoffrey Holt) or, indeed the writer (Anna Holmes). This is not how we usually receive poetry – even in the theatre. It ensures that the poem lives not only in wholes but in selected parts that seem to repeat themselves. You hear a voice speaking the poetry but you are also inwardly reading the words to yourself. It is as if you formed part of the production’s collaboration and the poem was an actor and dancer too.

So why do we need to see this whole work in three clear parts, with three stories as one. I think that is, in part, because the work is about the fragmentation of experience and about the slippage between interior and presented meaning. The first story opens with a young man trapped in the ‘shed interior’, his bodily movements, in the form of jerks made rhythmic by skilful crafted repetition as dance, occluded by the set wall and the grid of its windows. He is variously living out the chaos of a disrupted life, animated by the throwing about of littered clothes and bins of debris – beer cans – that speak of the disorder of his life. That he appears to attribute to the loss of his male friend who has gone to university, although expected home. That colleague is, even on return never confined to the interior of the set. He enters externally and even uses his exterior positioning to engage with the audience as if participants in the clubs he has attended with the boys.

When these boys are mentioned the first (the interior) male becomes even more disordered, no longer able to enact the harmonies of dance his friends return had made possible – in dancing the use of a video game (displayed on the front of the set too).

This is not ‘friendship’ that is of a different nature to the heteronormative story in the second ‘act’ of the piece. The dancing involves proximities that are heart-aching both sensual and near romantic. They ma indicate interior feelings rather than events, but that is the beauty of trans-generic art – it plays on boundaries that often shut us out.

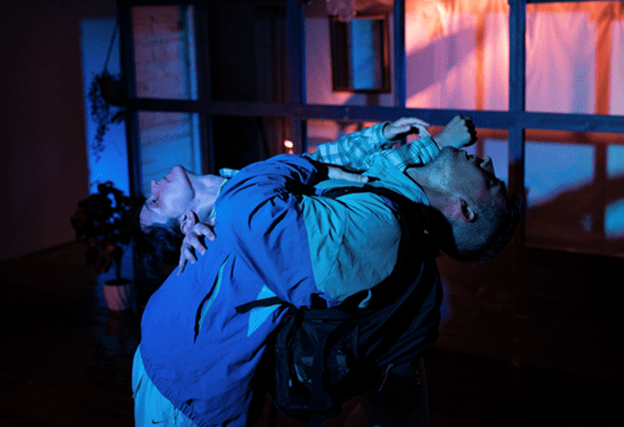

Likewise the way in which love and hate mix in dance-steps that play with proximity and distance and pace to associate with the difference of caressing to violent touch between males (but not only – for these interactions rhyme with moves by the two females in the last act). Such transformations of caress into violence also help to interpret the suicidality of the interior male in the second story. It hurts this section of the drama.

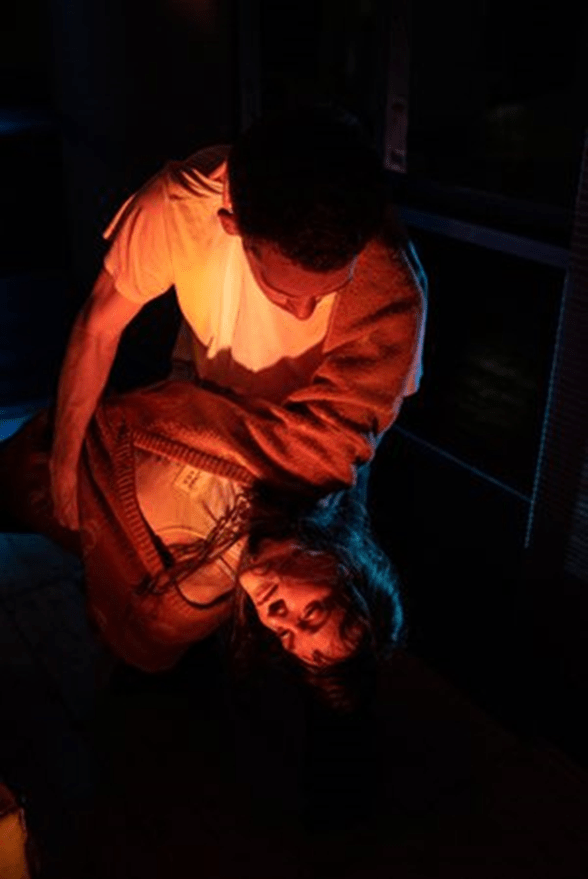

However dance mime gestures have to nuanced – never have one interpretation, not least because they are rhymed in different sections. Below see that caressing-throttling gesture played out in the second act where both male and female actor use it in some way suggesting the contortions of what living together as one unit means.

And, where motion and body sculping play a part so does lighting – not just ‘setting’ a mood but sometimes complicating it – softening a violent scene or hardening (or making terrifying – like a moment in a Gothic genre) an apparently fluid gesture. What my two examples below show you can guess yourself for yourself:

The final act moved me so much – because it was so much about the loss of what love might have meant in childhood, but also because it honed in on how misogyny ruins male as well as female lives – that it was the jewel in the crown of a very superior piece of art. In it there were even simple moments when what might in words have seemed feminist rhetoric only becomes so profound. This happens when the two females se their hair in ways that make them look like puppets dancing to another tune (presumably a patriarchal one). Even as a still it is effective – as dance and movement and locked within a confining frame that looks like a house-front it is more than effective. It converts. This is socio-cultural-and-political at of the highest order.

Last night we were told that the run of this performance was at an end. Demand more like this, or we will all become the automatons governments 9even Labour governments it seems) want us to be.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

[1] SHED — northern rascals https://www.northernrascals.com/shed

[2] Will Wrighton (2024) ‘SHED by Northern Rascals: a review’ in Yorkshire Bylines online (02-02-2024 06:52) available at: https://yorkshirebylines.co.uk/region/shed-by-northern-rascals-review/

[3] ibid