Reflecting on the Gay Bathhouse (not – let it be noted! – that I have ever been to one). A note on The Savoy Baths, 97, Jermyn Street, London and the compatibility of Artistic Mimesis with Surreal Invention in Christopher Wood’s Art.

As usual I want to do too much in this blog. My initial aim was merely to correct an error in my reading of the Christopher Wood painting, Exercises (1925). The error came to my notice as I read Chris Bryant MP’s new book; published first in 2020 and entitled The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler (London, Bloomsbury Publishing). A blog on Bryant’s book will, I think, follow after I have read it all. I had not expected to this book to mention that painting (or Wood) before reading it. The error concerns the subject of the painting, which Bryant, gay Labour MP and former Cabinet member, says is of a specific London venue: notably The Savoy Baths, once standing at 97 Jermyn Street, London WC1. Photographs of and about the venue, I take from the webpage which uses some of the same information as Bryant and which almost certainly preceded his book’s publication: http://www.nickelinthemachine.com/2011/04/the-turkish-baths-in-jermyn-street/ .

However as I reflected on the material I began to see other aims as necessary to consider for the purposes of my own reflective learning. This is so in particular because I had implied a kind of surreal contrast between the home of the well-heeled and influential, like the Glamour Boy MPs spoken about by Bryant, and the scenes of gay sexual licence that the well-dressed characters in the painting appeared not to have noticed. I’ll list immediately below (but not necessarily in the order of their treatment but for clarity’s sake in this introduction, the aims that grew on and into the project from that time.

- To discuss the source of meanings that commentators attempt to find in the analysis of paintings, particularly when the scene painted is, in part at least, an attempt to copy an existing reality. In as far as the painting then is motivated by mimesis, what does this do to the meanings we find in its design and content?

- To discuss further the meaning of queer culture in the early twentieth-century and why it is still preferable to not see this as a gay sub-culture but as something more generalised to the class-based experience of powerful men from the hegemonic ruling classes. In doing so, of course, we can also note how people marginalised from power-broking in that society also fitted into the social picture to be painted. I will do this in the Brant blog proper, or attempt to do so. (Now available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/04/11/half-in-love-with-the-male-camaraderie-of-the-regiment-reflecting-on-the-contribution-to-queer-history-as-a-side-effect-of-chris-bryants-2020-the-glamour-boys/ ).

- To reflect further on the ideas of experiences that we need to describe as culturally liminal in relation to representations of male sexuality and the architectural and social cultures it inhabited. In doing so, I intend, in passing, to return to a book about which I have blogged in the past (follow the link for the blog), Christie Pearson’s (2020) The Architecture of Bathing: Body, Landscape, Art, Cambridge, Mass. & London, The MIT Press.

I wrote about Wood’s painting Exercises (1925) on March 22nd 2021 in a blog on artists who died in their twenties (follow the link for the blog itself). I reproduce the relevant paragraphs from this blog below so there is no need to read the whole thing.

The most iconic of [his coded queer] earlier paintings, all kept in the private collections of people who, by and large, were both rich (or connected to the rich) and ‘privately’ queer (small cliques can be described as ‘private’) like Eddy Sackville-West and Mattei Radev, is Exercises of 1925. As the Head curator of Pallant House, Simon Martin, has suggested, in 2018, that an ‘objective selection of works, not leaving out those that may be deemed controversial or expressive of an artist’s sexuality’ was not commonly practice in the norms of the ‘curatorial process’ before the advent of explicit queer curation.[1] And though I agree that there is no doubt that Exercises ‘may be recognized as ‘queer’ by some visitors but not necessarily by many others’,[2] what speaks from this painting is mainly the opulence that associates exhibition with private ownership and a flexibility of embodied male sexuality to variations of public/private visibility and bodily touching. This is a painting that plays with what the expensively clothed and accommodated males in the relaxed comfort of a luxurious home do not see, or at least do not publicly acknowledge.

The range of exercises varies the muscle groups and domains that are visible as does the presence or absence of swim or gym wear. The pool has curtains that both conceal and reveal. The positions and gestures will seem sexual or like foreplay or neither of these to some but not to others – although it is clear that at least two men are positioned in touch and / or visual proximity to other men’s penises. Whilst others look down or away. The room is as most lounge and/or theatre as it is a private indoor poolroom. It is 5 o’clock on the timepiece shown but no-one stirs to leave for or away from ‘work’, because this place is not work. Hands brush or touch – in the clothed men they are hidden in pockets or behind a lounging head. They don’t work – unlike the hands we will see in some of Wood’s boat-building fishermen in the paintings later identified by the Nicholsons as his best work.[3]

Bryant includes this painting amongst his colour illustration with the following caption: ‘… Christopher Wood’s Exercises … gives a good impression of the all-night Turkish baths in Jermyn Street where men cruised and entertained one another with impunity’.[4] Bryant gives more verbal description of the context of the venues of queer London in the 1920s and thereafter venues on pages 39 and detail on the queer attractions of London Turkish Baths on page 69 – 71 inclusive. Some expanded details concerning the Savoy at Jermyn Street can also be found via this link.

Of particular interest in the latter sources is the identification of specific features. I, for instance had written, in order to link to queer themes that: ‘The pool has curtains that both conceal and reveal’. Bryant tells us much more that is much more specific of the curtains we see in the painting: ‘Bathers would push back a deep-red curtain to find a private cubicle with a bed, where they would undress …’, and presumably perform other activities, following on the opportunities released alter ‘men eyed up new arrivals’, and before visiting the basement Hamman where the ‘main action’ took place.[5]

The blogger ‘Nickel in the machine’ cites Derek Jarman’s stories (also in Bryant) of Queer Central London which also give a taste of the queer ambience of the Savoy Baths in Jermyn Street and the range of people that covered:

as a young MP, Harold Macmillan – who was expelled from Eton for an ‘indiscretion’ – used to spend nights at the Jermyn Street baths; anyone who went to them would have been propositioned during the course of an evening. I went there myself on two or three occasions. They were a well-known hangout: dormitory and steam rooms full of guardsmen cruising.”

Amongst the famous people to be seen there was Alec Guinness, who ‘wrote in his diary, “it all revolted me”’, though he ‘kept on going back’. Rock Hudson was another notary.

It was only in the 1970s that The New London Spy, ‘a rather self-consciously trendy guide book for London published’ (first) ‘in the late sixties’, wrote about the Savoy in Jermyn Street: “Sauna and Turkish baths are regularly raided and/or change management, check daily”.[6] Such raids were the death knell of these famous gay baths, which Bryant summarily describes thus: ‘To all intents and purposes these were sex clubs’. For him also to cite a painting (Wood’s Exercises) whose artist died in 1930 and who painted the painting in 1925 shows the longevity of the clubs and the ‘tolerance’, or more, that the ruling classes of men had for them.

And this brings me back I hope to my description of this painting. My rather abstract take on it at that point renders it as if it were a surreal invention typifying a social class:

what speaks from this painting is mainly the opulence that associates exhibition with private ownership and a flexibility of embodied male sexuality to variations of public/private visibility and bodily touching. This is a painting that plays with what the expensively clothed and accommodated males in the relaxed comfort of a luxurious home do not see, or at least do not publicly acknowledge.

What I miss here is that though Wood clearly selects from what he saw of a real venue, the divisions of ‘home comfort’ and a semi-public sexual playground were not invented by him as symbols. They existed in the way bathing architecture for the extremely rich few were actually built. Compare. for instance, Wood’s painting with a hotel from the period in which older architectural forms, preserved (at least in photographic formats) by Historic England’ LGBTQ architecture project, lend themselves to creating secluded subspaces and a pool in which people sit semi-naked lies alongside lounge furniture of a high calibre.

The same air of opulence is in combination with the same freedom to bodily exercise in Wood. Now this does not argue, I believe, that my analysis of Wood’s painting is in fundamental error but that the socially coded material, both psychosexual and sociological is as much a socially constructed set of symbols as an ‘aesthetic’ or iconographic one and that it is Wood’s design of the scenario, and placing of important icons (such as a clock) and curtains at various states and the viewing perspective these imply that summates and highlights these codes.

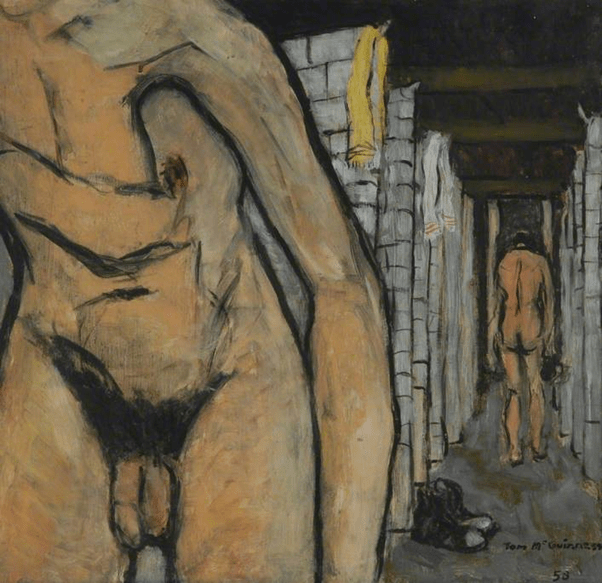

If contrast were required, compare this picture of working class miners at a new pithead bath (still a considerable luxury in the 1950s for NCB pits) below in a painting by the wonderful Bishop Auckland painting genius, Tom McGuinness. Here bodies have both functionality and the effects of a working day (in the short and more disabling long duration) etched on them and predict the re-clothing that will soon occur in the central position of the miner’s very typical miner’s scarves that decorate the functional stalls of the pithead bath.

Christie Pearson, an architect who has worked in and written about bathing architecture (see link for my blog on the book) has spoken, citing Betsky, about the long roots of a form of the public bathing where liminality is often at a premium, the gay bathhouse. It is not just that Wood’s Savoy baths predate the North American gay bathhouses which are her main discussion in a fine few pages, because in that piece she traces versions of gay public/private bathing as a ‘queer space’ to Ancient Greece and Roman thermae.[7] She also uses Michael Rocke’s (see my blog on the appropriate book by following link) work on queer space in fifteenth century Florence.[8] Queer spaces such as gay bath-houses illustrate for Pearson the depence of the social exploration of liminal identities, one considered to be well beyong the norm, to public regulation of those trials of new identity, entailing its regular if inconsistent policing to mark it as having liminal and perhaps as abnormal or illegal, as not tolerated, at least in theory.

So I have corrected my error but only by insisting that however ral the venue represented, mimesis is still feeding off inventive construction of symbols in a form of articulate design. Am I trying to have my cake and eat it.

[1] Simon Martin (2018:41) ‘Mediating Queerness: Recent Exhibitions at Pallant House Gallery’ in Katz, J., Hufschmidt, I. & Söll, Ä (Eds.) Queer Curating in Notes on Curating Issue 37 (May 2018) Available at www.oncurating.org

[2] ibid.

[3] From ‘Wood moved freely among Paris’s most elite artistic circles as he experimented with various post-impressionistic styles, bisexuality and opium.’ Does the history of art as a discipline on its own really have the skills, knowledge and values required in order to reflect adequately on the value of shortened lives? Reflecting on the case study of Christopher Wood in Angela S. Jones & Vern G. Swanson (2020) ‘Desperately Young: Artist Who Died in Their Twenties’. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

[4] See Bryant (2020). Illustration and caption appears on the third page of the first set of illustrations on the glossy pages inserted between pp.142 – 143.

[5] ibid: 69

[6] Cited http://www.nickelinthemachine.com/2011/04/the-turkish-baths-in-jermyn-street/

[7] Christie Pearson’s (2020: 67 – 73) The Architecture of Bathing: Body, Landscape, Art, Cambridge, Mass. & London, The MIT Press.

[8] ibid: 68f.

A very interesting read. l can’t wait till this covid confinement is over so that l can continue my own private research into into gay saunas and their goings on at a practical level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good luck with the practical research, Ralph.

LikeLike