Reclaiming space – a project in Black British identity in Derek Owusu’s (2019) edited essays by Black British men Safe: On Black British Men Reclaiming Space London, Trapeze, Hachette UK company.

Identity politics is going through a bad time. One reason for this is, as Derek Owusu, the editor of and a contributor to this book, notes:

…inaccurate impressions and ideas about Black British men are everywhere. …on social media, on dating apps, in foster care, in interracial relationships … and, often forgotten, in spaces traditionally occupied by Black People, like barbershops and our countries of origin.

p. 2, Owusu, D. (2019) ‘Introduction: Is It True What They Say About Black Men?’ in Owusu, D. (Ed.)Safe: On Black British Men Reclaiming Space London, Trapeze, pp. 1 – 6.

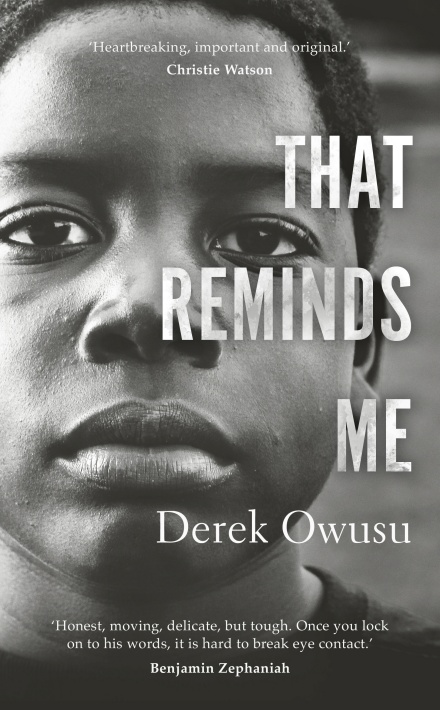

As E.P Thompson used to say in criticism of Louis Althusser, if ideology is everywhere, from whence springs the capacity for change. It is possible that this is what has gone wrong with ‘identity politics’: it has assumed that there is an identity shared in groups that is always true and consistently accurate. Hence Owusu asks for space in which black men develop identity markers, often with contradictions between each other based on defining experiences as Owusu did in his wonderful verse novel from 2019 about experiences in foster-care and adult mental-health services, That Reminds Me.

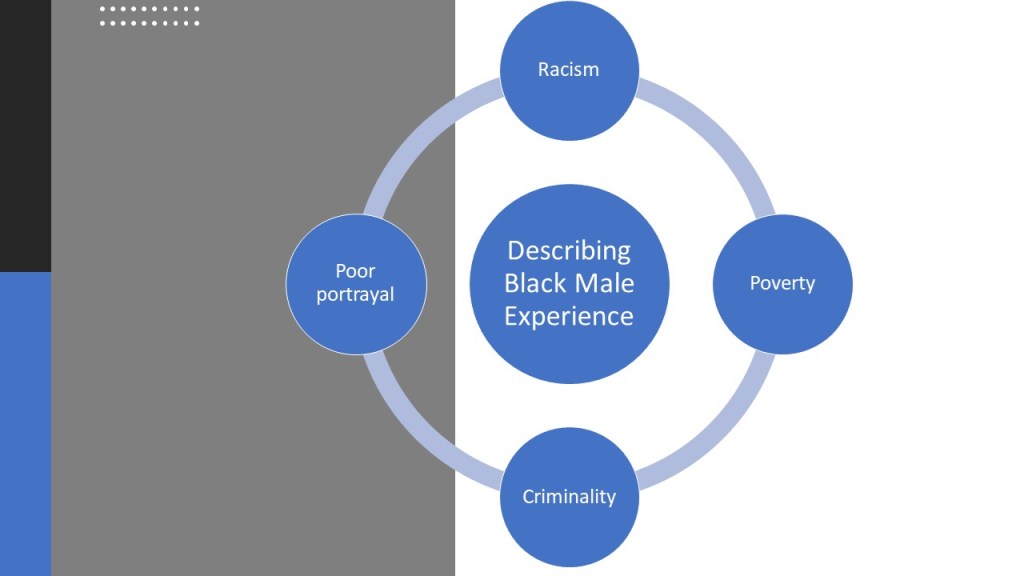

That Reminds Me is a novel I have already written a blog upon that tells truths about the experience of mental ill-health that few want to know, but they are also truths know to the care-experienced and people who use and survive mental health services. It literally cut me in its treatment of cutting. But as other writers in this say the stories that tie black male experience to the all of the disadvantages of a racist society may also not leave space for other stories – for more accurate truths for different and other black men. This can be seen as a negative basis of identity, which Nils Abbey in this collection identities as a negative and ‘poor portrayal of … Black Men in particular. It recognises’ racism as an aetiology of poor portrayal but seems too ensure a cyclical fulfilment of racism’s prophecies. Here is my graphic version of the cycle Abbey describes in bullet points:

There is a sense in which black male identity has also been specialised to the academy and studied under the heading of structural disadvantage, without it benefiting young black men at all. I find Jude Yawson’s statement here moving and so right, that I can’t see why it could not and has not been addressed, but it hasn’t. Of course, the reason I can comfortably think this sits with my white entitlement – with the fact that I haven’t HAD to experience this kind of oppression and invisibility.

Questioning the depth of our education system and why learning about the various identities that make up this country is restricted to expensive intellectual property at universities. All these notions are conscious and subconscious burdens that impact younger generations and leave us with no strong narrative to understand where we are coming from.

p. 168, Yawson, J. (2019) ‘ Existing as a Black Person Living in Britain’ in Owusu, D. (Ed.) op.cit. pp.167 – 178

Writers reflect as Franz Fanon did first in Black Skin, White Masks on the sexualisation of black males that emerges in beliefs about rhythmic dancing and penis size and which more than one commentator adduces as a personal experience, even up to people fondling, or approaching to do so, their genitals in public. In truth this sexualisation takes many forms, either in terms of the fearful fantasies of appropriation of the white race explore by Fanon or in everyday assumptions about and by some white women explored by Courttia Newland in relation to his own sexual and career history. Here he speaks of a white female copy editor:

Almost right away, my editor began making personal comments that I found highly unprofessional. She had black women friends, she said, who would ‘love me.’ she said I was cute, and sometimes when we were sitting at a desk side by side, she’d stare into my face when we were meant to be working. …

…

… I was perceived to have no recourse, no agency. I had to submit to being exoticised, and when I refused to reciprocate I was punished.

p. 62, Newland, C. (2019) ‘And Me …’ in Owusu, D. (ed.) op.cit. pp. 61 – 69

Apart from my knowledge of Owusu’s great verse novel, I came to this book via Okechukwu Nzelu’s brilliant 2019 novel The Private Joys of Nnenna Maloney which plots a similar exoticisation of a black man by a white gay man as part of its sub-plot. In contrast, Nzelu’s essay here is a fine piece of writing, using very precise and almost traditional literary irony to show how a young black gay man attracted to wearing pink shorts negotiates space for identity that negotiates the relationship between him, black Christian communities, Igbo heritage and the existence or non-existence of God. It is as if God was the ‘space’ that Nzelu wants to reclaim wherein he meets no prescription of his identity that misses out one jot of what he knows he is, even if what that thing he is remains only partially known to him:

Imagine if there was a being who’d seen you at your most proud and your most vulnerable; someone who knows you deeply and is unafraid of that knowledge. …: who thinks that all the different things about you that other people find anaomalous or threatening or unknowable are actually pretty great.

p. 135, Nzelu, O. (2019) ‘Troubles with God’ in Owusu, D. (ed.) op.cit. pp. 127 – 135

Now I still know that, as white cis gay male, I have not experienced the major oppressions faced by all of the men here but I do recognise those described by Nzelu in relation being a gay male in relation to a heteronormative and homonormative culture and why this makes for some version of those oppressions, though not so deeply structured as by racism. They are there to in Musa Okwanga’s essay. His comment on how and why we recall the pain of exclusion and oppression makes the analogy between black and queer men:

… I remind myself that it is not my fault if I do not convey the pain so well; because, as many queer people know, the trauma of coming out can be so extreme that your body often defends you from all memory of it, making you blank out whole weeks and even years of that period when you thought the world was ending.

p. 99, Okwonga, M. (2019) ‘The Good Bisexual’ in Owusu, D. (ed.) op.cit. pp. 99 – 107

I find that meaningful and it allows me to see how it might be necessary to work through the trauma of being dropped into a system that in its macro-representations fails to include you and the family micro-experience of your identity too in cases. It prompts in me too the sense that sometimes we live as in post-trauma defensiveness, revisiting those worst experiences of pre-coming-out experience as gay men, that make me prickly with straight people who use terms of me or other gay men like ‘queens’. That prickliness may be unhealthy but it marks the lack of adequate models, even in one’s own head to deal with the experience of past exclusions and their shadow and legacy in larger society. Instead we find as Okwanga did, in relation to in the interactions between being Black Ugandan (where being gay is heavily oppressed), Black British, and bisexual, found ‘my own island of happiness’.[1]

If you have not heard of these writers and are white, this book can introduce to them in a way that doesn’t carry assumptions about ‘black writing’ or ‘black art’. If you have, it still may have the same effect because of the diversities on offer here, not all of which you need ‘like’.

For instance, Robyn Travis’ chapter (‘Prisoner to the Streets: A Mentality’) takes such a therapeutic tone that to me (rightly or wrongly because there may be ironies here) that I see it like a CBT manual for avoiding the effects of racism and the ‘poor portrayal’ cycle described by Abbey.[2] It ends with Helen Keller. It may be that such a therapeutic perspective will say a lot to black men that it doesn’t say to me. Or it may be that I am cynical of cognitive models of oppression being seen as sufficient. Or I may just have read it wrongly.

I’ll end with Owusu’s own delicious contribution, other than the Introduction, which I absolutely love – although nowhere near as much as his verse novel. Owusu has carved his life out of his skin by cutting that skin and that has addressed a need without fulfilling it – but at least it has now been addressed. Many other care-experience accounts from black men and women can say the same. There is no therapeutic and reductive account of this, just a sense that space needs to be given to expression, however painful for others to contemplate:

I was numb then but now I feel intensely. But the numbness I can summon, ask to dull an emotion I don’t want to feel or that I can’t control. It’s why I can cut myself so easily, watch my skin split and the white flesh slowly appear like the back of a shark rising out of the Black Sea. … But beneath it all, I struggle to see who I really am. In my calmest moments, I am the most lost. But although I, no, we, have been shaped, by the events that pull us apart before hardening us into something unbreakable, we can learn to throw the clay and turn our space into the Potter’s House.

p. 24, Owusu, D. (2019b) ‘They May Not Mean To But They Do’ in Owusu, D. (ed.) op.cit. pp. 17 – 25

That metaphor and it’s play with black and white may seem to help us understand Derek’s pain but it merely paints it in a slash of blood and pain rather than with the cool thin lines of solution. Indeed the lynchpin of this passage is when Derek refuse ‘I’ as the subject of a sentence and turns to ‘we’ instead. Who is that ‘we’? All Black Men, all men, all people? The point may be that you don’t avoid the ‘Potter’s Wheel’ however the clay of your flesh falls after.

Ay, note that Potter’s wheel,

That metaphor! And feel

Why time spins fast, why passive lies our clay,

Thou, to whom fools propound,

When the wine makes its round

“Since life fleets, all is change; the Past gone, seize today.”

Robert Browning from “Rabbi Ben Ezra”

Steve

[1] Okwanga (2019: 107)

[2] Travis, R. (2019) pp. 117 – 126.

8 thoughts on “Reclaiming space – a project in Black British identity in Derek Owusu’s (2019) (editor) essays by Black British men ‘Safe: On Black British Men Reclaiming Space’”