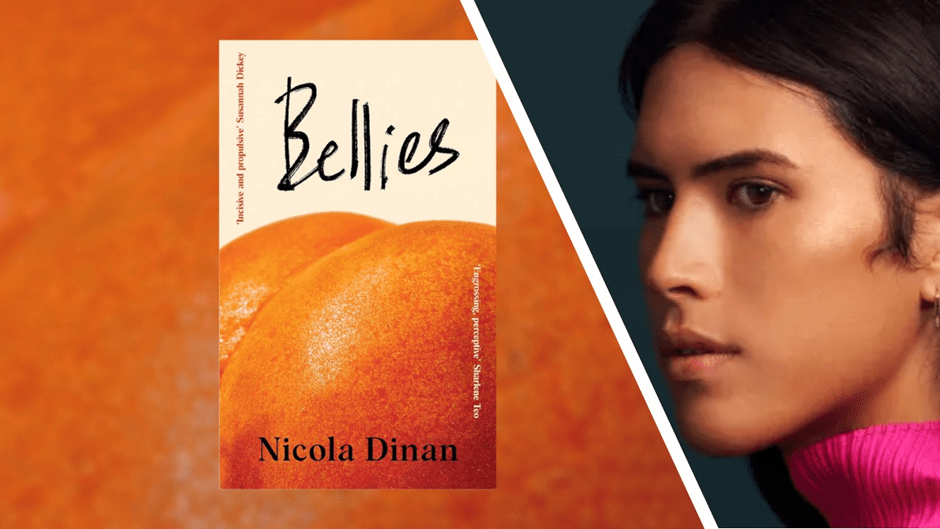

‘I placed my ear on his abdomen and listened to the low gurgle under his skin. The system beneath it seemed larger and more powerful than the belly of a boy. … I shut my eyes. It was a dark and endless canyon. The deep deep sea, outer outer space’.[1] In the interplay of exchange between initial human contacts and the making, sustaining, breaking and even intuiting of a serious ‘relationship’ between persons, we too often make abstract commentary about the issues and, in doing so ignore the demands of what it means to live in the space in and between our bodies, at our peril. Bodies are powerful systems in the making and breaking of the roles we inhabit in relationships and we understand them in their visceral reality or not at all. This is a blog on Nicola Dinan (2023) Bellies London, Transworld Publishers, Penguin Random House.

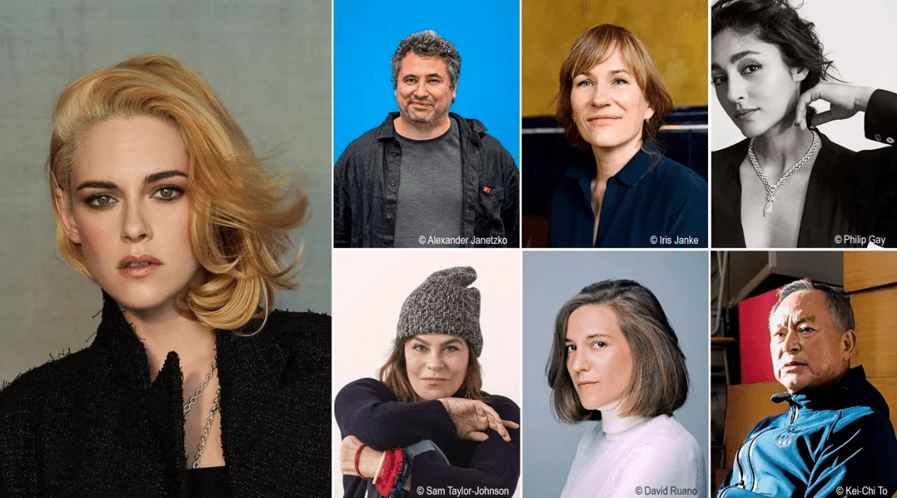

This book has been well received and is being televised by the makers of the enormously successful Sally Rooney’s Normal People. It will make a fine serial romance with scenes in Kuala Lumpur, Cologne and New York as well as chic fashionable London to give it a zing additional to Rooney’s story of relatively comfortable lives fissured by romance and sex. Although well served by a rather brilliantly perceptive review by the excellent queer writer, Jeremy Atherton Lin, in The Guardian, even this review underplays what I think is the novel’s wisdom about the nature of the dynamics of relationships in the queer world.

Atherton Lin makes perceptive justification of the way the narrative toggles – in uneven (and therefore partly unpredictable) sequence – between Ming’s narration of the story and Tom’s, saying: ‘the dual perspectives elegantly enact themes of transition and relationality’. However, the stress on elegance in this statement and on the book’s constantly youthful and superficial feel can seem, despite protestations otherwise, to rather undermine any claim to seriousness beyond the representation of a group of the young and the privileged, being, as he says, ‘always attentive to the surfaces young people construct and navigate’ (my italics). Atherton Lin’s review I think tends to hint at subtlety around issues of ‘transition and relationality’ but not to illustrate them convincingly. He is more interested in the details of the convincing representation of these young lives, much in the manner of Sally Rooney at her televisual best. One piece in particular of the review captures that interest with a list of the minute observations that are aimed at ‘depicting intimacy’:

Tom and Ming listen to each other’s bellies gurgle, watch Britney Spears’s snake dance on a laptop and practise Meisner technique, a theatre exercise of closely observing a partner’s actions.[2]

Lists are in their nature reductive but here that effect matters I think because, in my view, the moment of listening ‘to each other’s bellies gurgle’ (which I cite in the novel’s own words in my title) not only gives justification to the novel’s title (Bellies of course) but also begins its deft play with how surface detail interacts in the novel with what is deeper and beyond the superficial. In particular, it is an analysis of how modern communities construct the idea and the lived experience of relationships, and perhaps even define that word ‘relationship’. That is then my theme in this blog.

I do not know Sally Rooney’s novels themselves, though Rooney is read by Ming, one of the central foci of the novel (the other is Tom whom Ming falls for whilst he is still a troubled but fun-loving beautiful young man at a glittering party where both look great in drag). Ming reads Rooney partly because Ming too is a writer too who is obsessed with how relationships are compact with the themes of development of individual humanity and personhood, though she lacks Dinan’s wish to see alternative perspectives to her own, like Tom’s and Rob’s, as things that matter in themselves. Ming, unlike Rooney and Dinan, is a playwright and this fact becomes part of the novel’s drama (although the quality of her writing in ethical terms may be questionable). That is because the relationship with Tom becomes integral to a play called Thin Frames mainly about Ming’s transition, in her persona in the play as Li, to womanhood.

The title of that play is indeed relevant, for a thinly framed play is the equivalent of the kind of superficial it is easy to see operating in this truly beautiful novel. It is also beautifully satiric of the fact that thin body frames are very apparent in the novel’s main characters, both characterised, as Atherton Lin recognises too , with a certain fey beauty that isn’t immediately recognisable as the story of real relationships between real people in a real world. And thinness, which Ming aspires to even more as she transitions to a woman who desires an hourglass figure, is a remarkable thing in a novel where so much food is purchased, consumed and often glamorously described. That is where, of course,food does not mean the staple of steak for men and sea-bass for women in bourgeois dining rooms, or oily canteen sausage scrambled eggs for office workers, in the novel.[3]

I think we will need to look at food more carefully in the novel – the internal processing of which causes after all the gurgling and other sounds made by bellies. Digestion of foodstuff is rarely, if ever, apparent in novels but is so hard to avoid in this one. The short passage I cite in my novel is the only one I think that presses one’s face onto the evidence of its characters’ internal digestive process and equipment so clearly. But reference runs throughout to stomachs and bellies. Of course the stomach is an oft ignored seat and measure of emotional process as well as digestion – hardly surprising in an organ so surrounded as it is with neuronal connectivity. From the first page, as male bodies are squeezed into drag (Tom into a ‘leopard-print dress’ for example), the stomach registers response to the perceived transition of the self as seen in a mirror and ‘as I saw my reflection’ says Tom, a ‘bulb of dread had flowered in the seat of my stomach’.[4] Later, hearing Marco refer to Ming’s play Thin Frames makes his stomach react in lieu of oral discourse: ‘My stomach dropped. I stayed silent’.[5]

At another time, thinking about his past sexual relationship with Sarah (now a lesbian and living with Lisa, Ming’s co-writer) his thoughts feel as if they are food-colouring mixing in water and his stomach ‘warps from the closeness of her body to mine’, as they dance. The stomach is a busy organ. Tom realises this in his own transition, turning from sex with women, and here Sarah in particular,to men. At the same time he realises thoughts of not wanting something to knowing, saying or living the changes required (I précis the passage here): ‘My stomach twisted again thinking about it’.[6] I hope the analogy created by the reference to the physical stomach and food-colouring here which suggests that digesting the truths of one’s emotional nature and relationship capacity is as physical as the digestion of food.

Sometimes, the two processes (of thinking about a partner of some kind and hearing the demands of our digestive system) just appear contingently in the novel, without a thematic connection being pointed out in the writing explicitly. Trying out a sexual encounter with a blond boy in a gay male sex-club, who turns out to a model with undetectable HIV blood readings the latter resists, when they have sex, Tom’s wish that they use a condom. Such stuff is the stuff of decision-making in post-HIV gay male casual sexual relationships. After their sex, it looks to everyone, including the reader, that this man (we will, at the end of his short-lived appearance, know him as Ben – for this encounter will come to nought very soon) that their relationship may have a future.

After sex in the club they sit on the grass in the park, Tom has his belly exposed in the sun. Exposing the belly is a motif associated throughout the novel – and often in Tom’s idiomatic term examples that exposing one’s belly is a sign of animal trust in the other (like a cat that lies on its back to its owner or another for instance). He uses this idea near the novel’s end in talking to Ming to symbolise to her the trust that might in a loving relationship she tentatively describes [7]. Having no assurance now of a future with Marco, who had been supposed to be at the sex club, Ben (not yet named in the novel) piles grass on the exposed skin over Tom’s belly. Ben’s attention to that surface is drawn to it by the noises of digestion: ‘My stomach rumbled. I hadn’t eaten much’. Both acknowledge their hunger and go for dinner – where they order a ‘rare beef pho’ for both of them that reminds Tom of eating with Ming. Hunger fulfilled is intercut with talk of a possible closeness between the two: Tom feels he even finds it ‘hard to admit’ whether he wants ‘a relationship’ and Ben say equivocally that, though a ‘boyfriend’ seems a good idea, ‘sex can be safer and simpler. Relationships can feel a bit scary’.[8] The visibility or audibility of bellies often accompanies appetitive talk where the very nature of what it is in a ‘relationship’ that satisfies one is the substance of thought and dialogue between the young men. It is a conversation Tom will also have with Marco later, where the very word ‘relationship’ is fraught with responsibility Marco just does not want, though Tom does – whatever that word might mean – monogamy or some relationship primary to others. However: ‘“I don’t want a relationship,” Marco said’.[9]

A pho with beef

At one time, just before the novel’s ‘Epilogue’, the realisation between Ming and Tom – narrated by Ming here in the present tense (for only Tom tells a past-tense narrative) – that their relationship as lovers is effectively over and shall not be resuscitated makes ‘Time’ stop ‘a little while’: that is until the belly makes its presence felt and the hunger for a real future, one sustainable in reality not fantasy, has been felt: ‘I could stay here forever, even though I know I can’t. … We sit for a while longer, and then my hungry stomach rumbles, breaking the quiet’.[10] Even before that moment, in an episode where Ming steals into Tom’s bedroom at his parents’ house and they attempt a sexual resuscitation and recovery of romantic love, they find, despite his protestations (men all over, don’t you think) that he’s ‘hard’, he eventually has to give up over-trying, become ‘stilted and weak’. Finally, in resignation that this kind of relationship is over, he stares ‘down at his soft dick’. It is at this moment Ming recalls the fact that she (at that earlier time identified as ‘he’) once listened to the hunger in Tom’s belly and ‘liked listening to the murmurs of his stomach’, only to find at this moment on Tom’s bed that her ‘body is cold’ and now everything ‘feels still except my beating heart’.[11]

If you are awake to cultural associations, the fact that whilst a beating heart is no guarantee of romantic love, a still stomach is a sure sign of its absence is beautiful and interesting and reconfigures how novels use the ‘body’ in romantic and sexual contexts. The passage here refers back to that I have oft cited and will quote again (the prose is in the past tense and is Tom’s perspective) from my title, for a closer look. In a longer extract, I start the excerpt now as Ming:

… placed his head on my chest, sliding down from my ribs and on to my stomach.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“You can hear everything,” he said. “Not in a gross way but it’s soothing. I used to lie on my mother’s stomach when I was younger. Try it.”

He lifted his head and sat up. I placed my ear on his abdomen and listened to the low gurgle under his skin. The system beneath it seemed larger and more powerful than the belly of a boy. Ming stroked my hair, and his hand covered my ear. I shut my eyes. It was a dark and endless canyon. The deep deep sea, outer outer space’.[12]

This passage, so near the beginning of the story, has a number of functions. It opens Tom to an understanding of love and loss both, one Ming feels for his mother, who died when he was a young boy but whose presence is revived in the basic processes of life heard in another and not considered as ‘gross’ but as kind of beautiful mystery (including the need to eat and digest what we eat as we take in and give out love from our bodies that each of us digests so separately) . What Tom hears may evoke either deeply meaningful and / or feminine images, for it certainly transcends those of being of ‘a boy’. Images of sea, endless space and deep fissures that go beyond abstraction that pretends to name objects to a kind of supra-subjective mysticism: these are iconic in Jung, for examples, as archetypal of Woman. It may also be meant to evoke and predict the novel’s story which neither of them are able to understand yet. But mysticism it is not really; it is the willingness of lovers to hear each other’s bodies talk indicating needs greater than those they each can fulfill alone for each other and not be afraid of those greater needs. For we all need to eat what we are able to eat, what our body will not reject – hence the importance in this book of Cass and the sound of her bulimic retching of food she cannot afford to digest at this moment of her life because of unstated ‘issues with food’.[13] It is then, in this context I think, that we can go on to consider the iconic, symbolic and cultural significance of food in this novel, for significant it certainly is – and I think kind of beautifully innovative too.

There are so many instances in the novel when eating food, and beginning to digest it (or not, for the process is often blocked by reaction to thoughts and feelings raised in group conversation or stimulated in individuals over a dining table) run alongside the attempt of young people to digest the meaning of their own body reactions in the initiation, making and breaking of relationships. One of the finest is a long passage set in ‘a chain restaurant’ (possibly a Pizza Hut with its ‘red pleather benches in a booth’ and ‘stubborn shoelaces of mozzarella’) where Rob talks about the transition from heterosexuality in a relationship with Sarah to feeling his body responded only to men and Ming speaks about her Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) that will morph into her recognition that Ming is and wants a body (and pronouns in language) more consonant with a woman irrespective of genital markers.

Consider, for instance, the mix of psychodynamic language regarding sexuality and look of what I am convinced was a pizza slice from my own youth (as false in its imitation of real food as Tom’s sexual pleasure with Sarah was of a genuine sexual relationship) and is about digestion stopped off before completed or even before ingestion or swallowing:

I coughed. The bit of pizza wouldn’t go down. Ming’s expression remained casual, patiently waiting for me to stop choking. We’d arrived at my repression. I set the slice on my plate, now a doughy trapezoid. I imagined myself slumped over Sarah, our synthetic moans competing in volume and deceit, … (my italics).[14]

But even in this faux Italian food venue, the role of culture and the food appropriate across differences of culture arises with Tom telling the story of how he mocked and bullied ‘Krish at school for eating with his hands’ and was reprimanded by his teacher father and psychotherapist mother for mocking ‘people for where they come from or their cultural practices’.[15] Hence the importance of the exposure of Tom and the reader to foods, of which even the names – often deliberately unexplained – bespeak how food engages the socio-cultural psychology of how appetitive pleasure and desire is formed and gets attached to food names. To illustrate this think of Tom observing Ming in his Malaysian home now eating and talking about food with ‘the kind of smile that came from his heart’. Yet again then belly-heart-and-desire are implicated in food. Similarly, how divorced from any heart-felt thoughts Tom is in the novel later, and after the death of Rob, is emphasised by his reliance on the most faux of Italian foods that characterise British eating habits: microwaved frozen lasagne.[16]

The food Tom reacts to in joy because it comes from Ming’s familial culture is kuih, which Tom finds ‘surprisingly oily in my hands’, a silent breakthrough for this style of cultural practice in eating with the hands for Tom.[17] Ming becomes acculturated to such food by the exigencies of being in love with Ming, even though it is insisted he eat food that he describes in retrospect in ways that slightly alienate and disgust such as ‘rectangles of bean curd with rounded corners, the fish past sitting in the centre like the dilated pupil of an eye’. Nevertheless, he not only says he loves them, he confirms afterwards that, ‘I loved everything Ming ordered’.[18] As a fan myself, I love the introduction of Tom to roti canai, dipped into fish curry, which he again says he loves like any other ang mo (another unexplained term used by Ming’s stepmother Cindy, being a slightly derogatory term in Malaysia for white people).[19] Later, and after the split with Ming, Tom makes char kuey teow for Marco, explaining it, of course, since he is unaware that, as an Australian, South East Asian food is well known.[20]

L: char kuey teow, R: roti canai (top) kuih (bottom)

The role of East Asian foods as an aid for health, and especially digestive health is continually stressed by Cindy, the Malaysian step-mother with whom Ming as a woman learns new love, support and the joy of girly nights.[21] Interviewed in an American bookshop and recorded for YouTube, Dinan spoke of how much easier it was for her to imagine and produce the voice of Ming undergoing the huge fact of sex/gender and cultural/racial transitioning than that of Tom, whose transitional experiences are less obvious (and dramatic) but are clearly there. Though the situational dynamics of the changes experienced by Tom are clearly less politically urgent in times when, as Atherton Lin says, it was ‘reported that transphobic hate crimes in the UK had increased by 240% in five years’, Dinan conveys them too to show that Ming does not do that in her play Thin Frames. This seems to support the view that Tom is right to think he and the pain he had undergo during her transition has been betrayed by her in that play, and which Dinan makes clear (in that interview but in one I cite later too) is meant to show her self-absorption to some extent, and make her the more rounded flawed character the trans novel still needs if it is not to be merely propaganda.

And I think Atherton Lin is right too to see great beauty ad truth in the picture of a character trait that Dinan tells us that she found much more difficult to write than Ming’s transition story, which is nearer to her own. The trait is Tom’s soft love and hot desire conjoint for what is hard and masculine.[22] It’s a quality of body in others I’d guess from the writing that Tom needs to know in order to experience his own masculinity and the fullest mutual love of which he is capable. There is a lot of play with the terms ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ in this novel, such as in the picture of the intolerable Jason who Tom nevertheless succumbs to as he ‘felt the power of his hard leg’.[23] The varied hardiness and showy bravura of the more acceptable models of the sexual male Tom confronts in the fashion models Ben and the longer-lived (in the novel) Australian Marco. Their attraction is brilliantly painted as if from Tom’s viewpoint which makes us feel their rejection of him, in the way he wants them, the more. But these men still do not provide what Tom needs, for theirs too is a sexually tuned masculine hardness only (and hence not unlike Jason’s), without the softness needed to bond with others and is conjoint with a fear of ‘relationships’ in them. In many ways Tom’s truest love, Ming aside, in the novel is, what Atherton Lin calls, for he – like me – seems to fancy him as much as Tom does, his ‘cuddly straight pal Rob’, who , if cuddly, is so only in a rather hard way.

There is such an unstated loving desire for Rob in Tom that theirs is the unsung love-story of the novel. This love is even noticed by others, like Viktor, their camp Cologne flat landlord, but more so by the reader who can’t, like Viktor, have their interpretations as easily invalidated as his are. Tom writes that: ‘I woke up with Rob next to me on his phone, his hair damp, smelling of oranges.’ Rob touches Tom’s forehead even before we get the sense of Tom’s haptic sensual vision of Rob’s body surfaces and hair being almost too close to be just comradeship. But I won’t consider this now, leaving it for other readers to construct, though I suspect it will be easier for male gay readers. The point I want to make is that the attraction between bodies, like that of friends Tom and Rob, often determines the feelings that shape the potential (if not always the actual) relationship between queer men in this novel even when these are unstated, explicitly at the least. Rob’s attractiveness as a character is moulded as fact though Tom’s implicit attraction to the best example in there of the hard body of a man with a soft acceptance of male bonding. Even though it seems an ideal relationship that will never happen, even if Rob were not to die, it illuminates the soft acceptance of primary togetherness – the side that makes Rob Tom’s best defender over his hurt about how he is represented in Thin Frames.

Tom’s love of male body hair should strike any male queer reader too as quite beautiful; for instance, the appreciation of Jason or Marco’s ‘dark patches that sprouted from his chest, a rich and tangling bed of keratin’.[24] The love of male body hair however also links him to the complex presentation of transition for a trans woman in Ming. It charts the fact that transition is something with an effect on more than one person, to those significant others for instance struggling but trying hard to understand a kind of transition they cannot imagine experiencing, and hence (given the nature of embodied relational desire so well depicted in this novel) have no wish to experience for themselves, in self or others. Transition for Ming starts with a kind of compulsive phobia about his own body hair, rubbing at his stubble ‘as if it were a stain’ when he is in Malaysia with Tom.[25] The beautiful scene where Tom watches Ming shave his legs (still him at this time) is also the scene where their relationship turns to irritation at their differences that Tom feels that Ming will not accommodate.[26] And in a brief article in Dazed, Dinan clearly makes the point that:

Ming is also no angel. She is often those things that trans people, and in particular trans women, are accused of: narcissistic, superficial, mean. There’s a scene where she attends a trans support group, only to pick apart the trans women around her.[27]

Watching the character, George, based on him in Ming’s Thin Frames, Tom feels negated in primarily because his right to mourn ‘a world … in which Ming wasn’t trans’ is negated, as is too the years he’d ‘spent holding her hand’ (my italics) during the pain associated for her with transition. The danger is that writers turn one into so much spilled ink – or in Dinan’s words in Tom’s intelligent voice as if: ‘The lines and borders used to define myself had faded, ink spilling on the stage’.[28] There is no doubt that Tom represents a fair and richly necessary point of view, for even Ming accepts in a late dialogue with Cass that the representation of Tom in Thin Frames caused pain to both Tom, and to Rob who loved Tom, and that she ‘shouldn’t have written the play’ or written it differently: written it like Bellies is as a novel for instance, with deeper respect and acknowledgement for the pain of others who truly care for him and her, before and after transition, in the wake of that transition.[29]

Bellies truly deepens the grasp of what the episode of transition might mean for one trans woman (which surely and correctly remains a primary concern) and others (which need not be ignored). It means the novel faces up to famous real debates in our current transphobic world but nevertheless gets the better of them, such as the fact of detransition (however rare that is) and the fact that a trans woman may still contain the memory of a pre-trans person living as a man in her consciousness – a fact explored in Ming’s working towards her putative play about a trans woman with dementia.[30]

However, as I write this I feel how inadequate it is as even a summary of this rich novel. I don’t think Jeremy Atherton Lin thought that of his piece. I think he should. Some art is greater than the impressions it causes at the first, and this is a book that needs time to settle in.

Some of the cast of the new Bellies TV series

I do recommend this novel. Read it before your see the TV version, though scripted by Dinan too. And if you love food, read it to see how it can be represented at its best and richest in writing as part of whole tapestry of lived life.

All my love

Steve

[1] Nicola Dinan (2023a: 13) Bellies London, Transworld Publishers, Penguin Rando House.

[2] Jeremy Atherton Lin (2023) ‘Bellies by Nicola Dinan review – the fizz of first love’ in The Guardian (Fri 23 Jun 2023 07.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jun/23/bellies-by-nicola-dinan-review-the-fizz-of-first-love

[3] Nicola Dinan (2023a) op.cit: 78 for the gendered food serving & 97 for the canteen food.

[4] ibid: 1

[5] Ibid: 180

[6] Ibid: 7

[7] Ibid: 298

[8] Ibid: 168 – 173.

[9] Ibid: 250 – 253

[10] Ibid: 311

[11] Ibid: 298

[12] ibid: 13

[13] Ibid:31

[14] Ibid: 26

[15] Ibid: 23

[16] Ibid: 240

[17] Ibid: 51

[18] Ibid: 53f.

[19] Ibid: 56

[20] Ibid: 177

[21] Ibid: 22f., & 277.

[22] Cited from Dinan interviewed in the following video: https://www.youtube.com/live/tgKQV0BpTDg?si=6dy1hxFpG19ETc64

[23]Nicola Dinan 2023a op.cit: 112

[24] Ibid: 176

[25] Ibid: 57

[26] Ibid: 102

[27] Nicola Dinan (2023b) in Dazed (6 July 2023): available at: https://www.dazeddigital.com/life-culture/article/60276/1/trans-art-and-the-complex-politics-of-representation-bellies-nicola-dinan

[28] Nicola Dinan 2023a op.cit: 161

[29] Ibid: 280f.

[30] See ibid: 191 & 220 for instance

3 thoughts on “‘I placed my ear on his abdomen and listened to the low gurgle under his skin. The system beneath it seemed larger and more powerful than the belly of a boy. … I shut my eyes. It was a dark and endless canyon. The deep deep sea, outer outer space’. This is a blog on Nicola Dinan (2023) ‘Bellies’.”