Once we accept interiority as primary, people aren’t around you or you around them. We are mutually absorbed. Some reflections halfway through Mark Haddon’s 2026 memoir ‘Leaving Home’.

Thoughts dedicated to a dear friend, Joanne.

I am reading Mark Haddon’s new memoir at the moment called Leaving Home, and will blog on it with as much objectivity as I can muster later, when I have finished it. However, I glanced at this question this morning and felt a strange revulsion at the idea of ‘being around’ ‘people’; people I am not asked to name but to characterise as a type: the people it is nice to be around. The more I think about it the more it becomes a thing I have militated against for a long time. I think maybe the problem lies in the phrase ‘being around’, as if I were choosing a type of person of which I wish to be in physical proximity,. Except I am asked to be ‘around’ this type only in as much as we are all multiples of tokens of that type as a group, where non-evaluative or hieratchical distinaction between us is meant to soften and perhaps dissappear.

It is as if, to me, the idea of ‘being around’ absorbs all of me, so that to ‘be around’ these people I must suspend, for a time at least, any kind of singularising idea of just ‘being’ a person made up of all the determinations and personal agency peculiar to ‘me’. I wonder if the phrase ‘being around’ disturbs me because it is a kind of dead metaphor that at some past time evoked the idea of geometric circles or orbital circling in dynamic physics.

Maybe the feeling goes back to hearing A. S. Byatt lecture on Tennyson’s In Memoriam, especially this lyric, number XLV:

The baby new to earth and sky,

What time his tender palm is prest

Against the circle of the breast,

Has never thought that "this is I":

But as he grows he gathers much,

And learns the use of "I," and "me,"

And finds "I am not what I see,

And other than the things I touch."

So rounds he to a separate mind

From whence clear memory may begin,

As thro' the frame that binds him in

His isolation grows defined.

This use may lie in blood and breath

Which else were fruitless of their due,

Had man to learn himself anew

Beyond the second birth of Death.

Byatt claimed that the motivating metaphor, of the whole auto-fiction that this poem is, was the circle. A circle is a definition of bounded space, although sometimes it operates in three dimensions so that the circumference of the circle, always a boundary, becomes a ‘frame that binds’ you into itself. To be thus bound might comfort, for we are bonded to ourself, and learn to know, and hopefully, love that self, but bonds also imprison us. When Tennyson names the development of individiality for the baby no longer ‘new to earth and sky’ (open qualities) as that proces by which ‘his isolation grows defined’,we feel the imprisoned nature of ‘defintion”.

Yet it is comforting not to learn yourself anew, the lyric voice thinks, but, within my reading of the line anyway, with a tone of hesitancy. But there is another circle identified in In Memoriam as a whole work, which is very different from that that defines and individualised the single self, a circle sometimes called the ‘social circle’. These appear at the nodes of this otherwise amorphous poem as ‘celebrations’ of family, religion and communities of likeness, at weddings, Christmas and, of course, New Year.

The rounding of the social circle that binds us in communion of a general likeness is often the mere shade of a metaphor like the holly ‘wreathed around’ the Christmas hearth, circling an icon of domestic familial warmth, or like the toast in wine at the wedding in the poem’s Epilogue.

Let all my genial spirits advance

To meet and greet a whiter sun;

My drooping memory will not shun

The foaming grape of eastern France.

It circles round, and fancy plays,

And hearts are warm'd and faces bloom,

As drinking health to bride and groom

We wish them store of happy days.

This is a moment where the lonely ‘I’ of tne poem circles into the social likeness of ritual and gets absorbs into the ‘We’. The wine is not only a toast to heterosexual marriage but a truer kind of communion wine. But heterosexual marriage is itself a shading down of the diversified celebrated in this poem, of a holding of hands Tennyson was never to celebrate as a ‘marriage of true minds’ in Shakespeare’s phrase; holding the hand of Arthur Henry Hallam that takes place only in dream fantasy:

Doors, where my heart was used to beat

So quickly, not as one that weeps

I come once more; the city sleeps;

I smell the meadow in the street;

I hear a chirp of birds; I see

Betwixt the black fronts long-withdrawn

A light-blue lane of early dawn,

And think of early days and thee,

And bless thee, for thy lips are bland,

And bright the friendship of thine eye;

And in my thoughts with scarce a sigh

I take the pressure of thine hand.

That poem, lyric CXIX, is probably, in my estimation at the least, one of the greatest ever written, at least taken as it should be in tandem with Lyric VII, the ‘Dark House’ lyric, which the former quotes in its first line. Just as we feel the sensuous ‘press’ of the hand of a man we love , but must not love, so we feel the pressure of the weight of social condemnation that men have sometimes felt when holding hands beyond a handshake, in public. Never have streets of houses been so cleverly both subject and metaphor of exterior and interior lives in interplay.

But Tennyson dealt with issues of exclusion and marginalisation in the context of the age of Victoria, where was not only so much hidden but much remained covert when actually expressed. This is how he dealt with queer themes and themes of self-identified madness, in Maud as well as earlier poems.

Mark Haddon writes his new memoir at a time which invites the confessional more than ever was the case previously, but sets so many conditions on the nature of the confession.

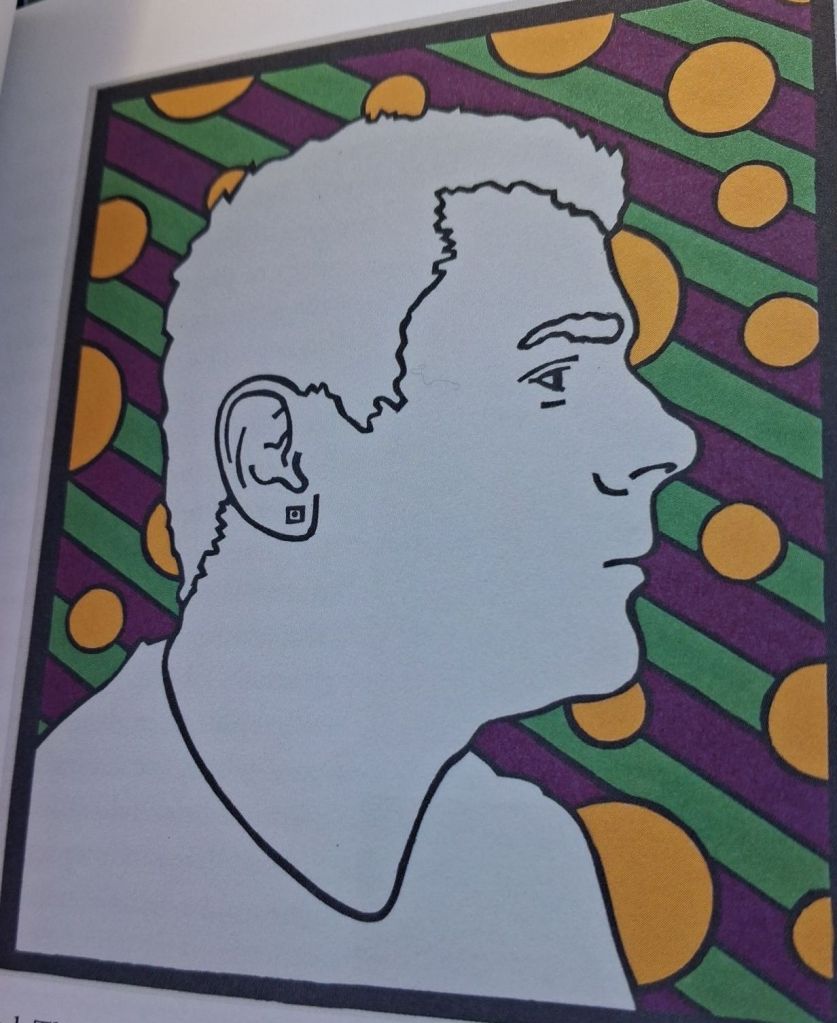

First modernity demands that the confession be resolved into categorical labels. Haddon shows this in a beautiful section, no. 9 of the book, in which, in order to rebel against his parents in a minimalist manner, he adopted ear-piercing jewellery, if but a tiny stud. His mother maintained a stony silence against him for those self-differentiations from family culture, at least to his face. Nevertheless. only a little later his sister is told by family friends, presumably after being ‘informed’ by her and Mark’s parents, that they were sorry to hear her brother ‘was homosexual’. [1]

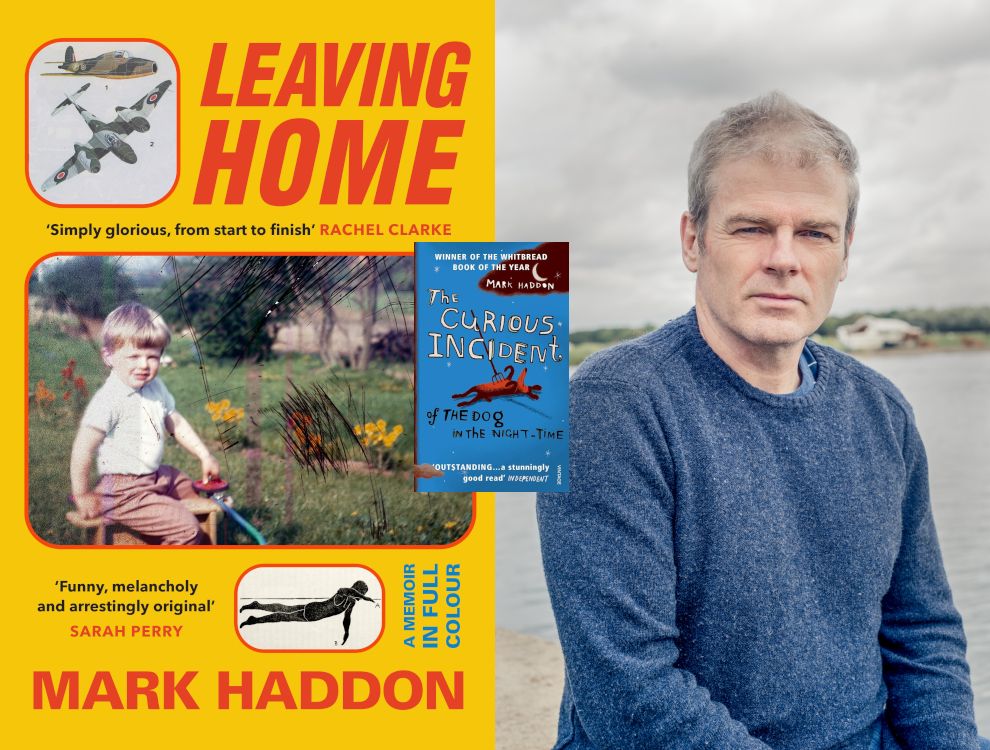

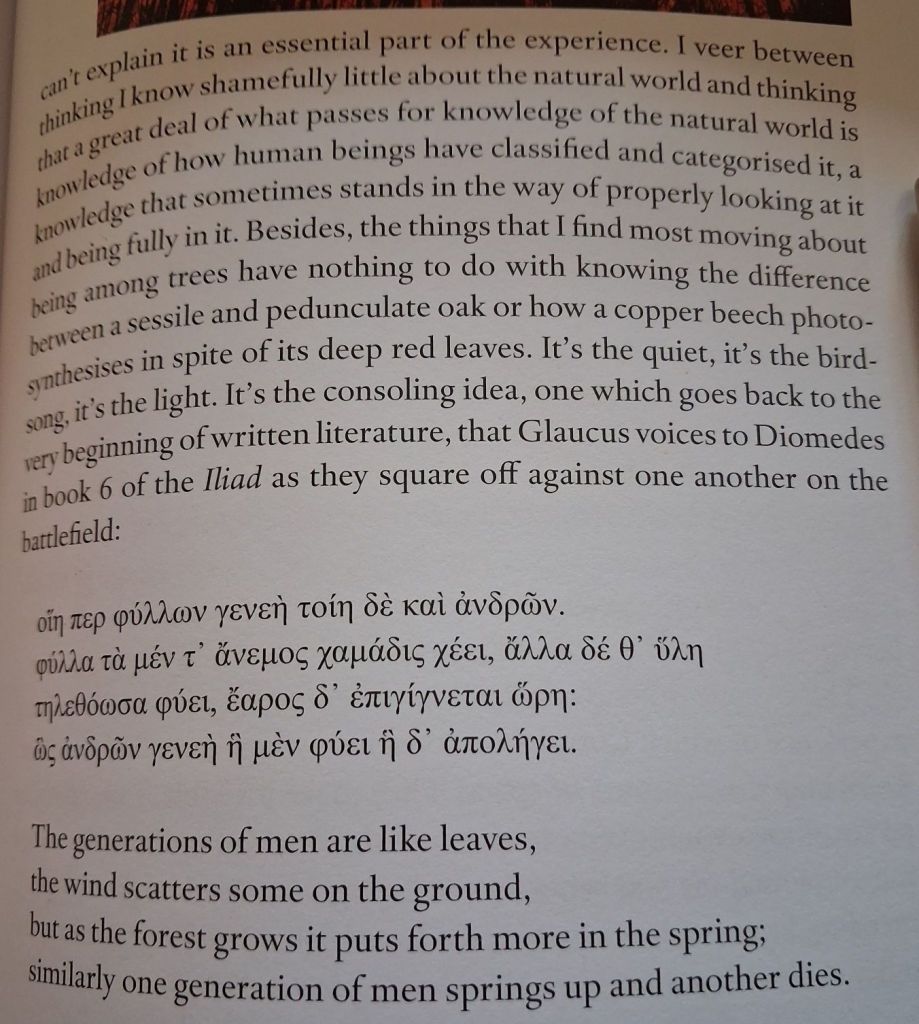

This is not a label that Haddon embraces though he clearly sees how his mental alienation is expressed in signs that the heteronormative thus misread. However, it was Section 57 of Haddon’s book that raised the central thought in this blog. For reading Mark Haddon, since I first contacted the wonderful Curious Incident of The Dog at Nigbt Time, made me discover that the sensibility that speaks through the substance of these books is the one I want to ‘be around’. It is a sensibility that shuns social circles, even meeting a random Danish boy and finding it an adventure in exploration of otherness, and prefers it’s own company. The extremity of that separation of self is felt especially in the passage (below) in which Mark explains his preference for solitary runs into and across wooded landscapes. [2]

For Mark not only prefers his relatively ignorant (as he recognises it to be) communion with external nature, and total disregard anyway for what passes as human knowledge about nature. That is because human knowledge of nature is really knowledge about the labels people attach to the external natural world in order to categorise and name it, not ‘know’ it. For naming and categorising things make them easier to subjugate to human control, for this in most people passes for ‘knowledge of the world’. It might be more truly called tooling the world (natural and human-built) for human manipulation and regulation. It is not that ‘knowledge is power’, it is that corrupted human beings require knowledge to be power because power is what they desire rather than shared communion.

Hence, ask me again about the people I want to ‘be around’ and I would have to say only those who, like Mark Haddon, realise the hardest thing is to be worthy of being alone with a world in which I don’t have to share the desire of dominating it. Most often tbose people are labelled as vulnerable or mad, as Mark labels himself sometimes – which makes him avoid ‘being round’ others in any kind of non-differentiating circle. You can’t just ‘be around’ with such persons, you have to be in them as if we were in one commune or communion. It is a sad world in which we accept loss in and of each other whilst still being in love, as in the quoted lines from The Iliad: “The generations of men are like leaves, ….”.

A page earlier than the last one quoted, Mark describes the sculptures made of cheap, easily available and perhaps vulnerable matter that he favours over high art and which former kind he makes himself:

Unlike sculptures made of glass or wood or stone, they have interiors, they have rooms and corridors, and their exterior surfaces are a function of those interior spaces. I look at them now and can’t help thinking of them as habitation, as buildings in which something lives. [3]

Once we accept inferiority as primary, people aren’t around you or you around them. We are mutually absorbed.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

__________________

[1] Mark Haddon (2026: 12f.) Leaving Home London, Chatto & Windus.

[2] ibid: 121 (my photograph)

[3] ibid: 120

One thought on “Once we accept interiority as primary, people aren’t around you or you around them. We are mutually absorbed. Some reflections halfway through Mark Haddon’s 2026 memoir ‘Leaving Home’.”