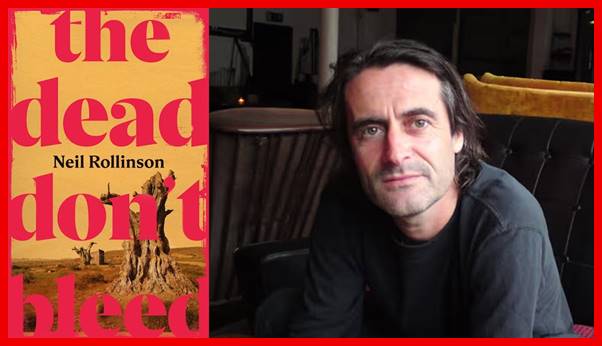

The best gift I have ever received is to allow darkness and obscurity to work on me, as in preference to relying only on what people present as light and clarity, or as Lorca says, ‘La luz me troncha las alas / y el dolor de mi tristeza / va mojando los recuerdos / en la fuente de la idea’. [Translated by D K. Fennell: ‘The light trims my wings / and the pang of my gloom / will moisten the memories / at the font of knowledge’ (the last line seems somewhat to travesty the Spanish)]. What follows is a blog containing some dark or obscure (for Lorca’s ‘oscura’) thoughts about Lorca as invoked by a new novel: Neil Rollinson (2026) The Dead Don’t Bleed London, Jonathan Cape. [There are spoilers with regard to that novel herein from the start].

I have just read a novel which feels so out of my domain currently. It is the debut novel of the poet, Neil Rollinson, published in 2026 (this year) and entitled The Dead Don’t Bleed. That is a haunting title and I did not recognise when I purchased the book that is a translation, the one made by the main protagonist of the novel, Frank Bridge, from a poem his dead cousin and partner taught him by heart. It is a poem I had read but had not recognised by a poet that I try constantly to learn more of and about, Frederico García Lorca. I especially always attempt to learn more about how to read his poems. That the novel is entitled after a Lorca poem was only recognised by me at the time when no-one could have missed it, for it forms part of a conversation in the novel, though the poem in this case is not named, but of the circumstances of the poem’s appearance I will have more to say later..

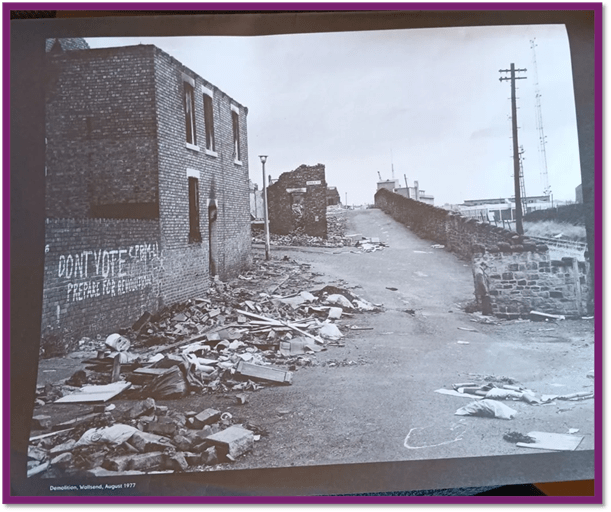

As we shall see later, the novel is all very much a ‘gansta’ genre novel, though much of its writing stresses fiction we usually name ‘literary’.This is not normally my sought-out reading fare, except that it touched on local geography and history of the North East, about which I am always interested!. And much in the novel feeds that hunger. The rather good novelist, Johnathan Lee, reviewing this novel in The Guardian, is absolutely correct to praise its fine and nuanced glimpse of social change in Dockland Newcastle, saying:

Readers of Karl Geary, Douglas Stuart or Ross Raisin will appreciate the way Rollinson blends social realism with a knack for capturing risky intimacies. The “creeping deprivation” of Northumberland in the Thatcher era – the closure of its core industries, “more and more lads on the dole” – is put in beautiful contrast with Frank’s longing for his brother’s girlfriend. In one lovely, expertly judged scene, Frank and Carol sit “on a wall by a waste ground” as the rain beats down around them. A “demolition squad takes down a terrace behind them. A whole street. Houses he’s known, and been in.” A fireplace “hangs, mid-air, levitating, its grate gaping. Improvements, they say. For whom?”[1]

I don’t see quite the analogy with Stuart, but the whole, with its finesse of political questioning included together with the realities of working-class intimacy building, across barriers (Carol remembered is ‘really’ Gogs girlfriend) is spot on. It reminds you of Chris Killip’s photography (see my blog at this link).

But Jonathan Lee takes the landscapes in this novel on trust because of this – and the Spanish ones matter enormously but trust in them may also need trust in the UK psychogeography. I nearly gave it up as I read a chapter set in Kelso in the Scottish lowlands entitled ‘Kelso, Scotland 2002’. The chapter tells of the funeral of Laurence Bridge. Described by Frank, one of his two sons, as a poor affair with only a few of the gangsters who once formed his empire still left. The loneliness of a kirkyard near the moors captures Frank’s elegiac mood, for however hateful his father he was still known as ‘King of the Tyne’. The chapter tells of the funeral of Laurence Bridge. Described by Frank as a poor affair with only a few of the gangsters who once formed his empire still left. The loneliness of a kirkyard near the moors captures Frank’s elegiac mood, for however hateful his father he was still known as ‘King of the Tyne’.

We find Frank trying to escape the mood that elegy implies, so replicated by the lichen-covered illegible script on the stones in the kirkyard and its surrounding low moors. Frank ‘jumps the wall and walks the beach, a mile or so into the wind’.[2] However, lets note that Kelso’s nearest contact with a ‘beach’ is in Eyemouth more than twenty miles East of the town. Kelso is not a coastal town, far from it – it is classically the midlands one. I have to say that I am not usually a sleuth of errors in novels, but this one hurt. I was ready to abandon the novel because of it so near its beginning – the novel having invited me in mainly because of its use of places I knew around me, only to bruit its ignorance thus. Moreover, because I read the novel because it felt local to me – in present geography at least, I know Kelso fairly well, in that, as I see it, it is just less than an hour’s ride by car up the A68 which bypasses Crook nearby.

But I let that pass by, because elegiac novels fascinate me. Frak’s lonely concern with his isolation through the death of his most significant other, his Dad recalls to him a line of Lorca, which I have now tracked down as coming from a very early lyric by Lorca known as Autumn Song (Canción otoñal) – I also quote this poem in my title, although the poem is not named in the novel, only the quoted translation below (Rollinson’s (via Frank’s) own translation):’If death is death, what will become of the poets and of sleeping things, that no one remembers?’ In the Spanish lines, this has an urgency no prose version can capture, that modifies its elegiacism and makes the point about being remembered as a poet, important for Lorca this early in his career, very pointed:

¿Y si la muerte es la muerte, qué será de los poetas y de las cosas dormidas que ya nadie las recuerda?

D.K. Fennell’s translation, by the way, prefers the imagistic phrase ‘things in a cocoon’ to the more literal ‘sleeping things’ in Rollinson, thus suggesting a butterfly metamorphosis that doesn’t seem to be in the darker original, which posits the potential of not waking up from sleep. That alone would capture me in the novel. But in truth, there is so much more in it, that lingers in the psycho-social depths of family dynamics and its psychogeography. Jonathan Lee captures all this well:

Rollinson is expert at capturing the long shadow cast by a complicated father. Laurence is a local gangster who, through his own perverse code of ethics and innate charisma, has established himself as “a man of stature. Respected. Everyone stopping to chat.” His “loud laugh echoes across the room. A man among men”. Frank is caught between wanting to please his parent and wanting to escape the family’s gaze entirely. His “father’s scrutiny is like a physical manifestation,” Rollinson writes, Frank “always feels it in his throat, as if he’s being throttled”. The novel captures the way close observation can be an expression of love, but also a kind of violence. In the Northumberland boozers where men “get mortal in the afternoon”, pints “glow in the river light, amber gold and black, like beakers in a chemistry lab”. Many of these men will drink themselves to death. What catches your eye can kill you.

And, what matters more is Rollinson’s capture also of the realities of working-class extended family life in the cultural geography of the 1970s, as in Lee’s brilliant summary of Rollinson’s treatment of Carol:

He is also dangerously drawn to his brother’s girlfriend, Carol, often glimpsed with a mop and bucket in hand at the local pub, cleaning up after the men. Frank “loves to watch her move: tough, big boned, elegant but strong. He’s seen her put men flat on their backs for touching her up. A single punch.” In north-east England, “no one messes with Carol” – …[3]

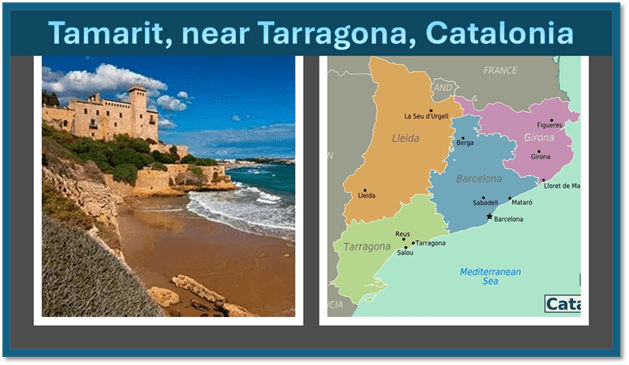

When Lee says ‘Rollinson writes, Frank “always feels it in his throat, as if he’s being throttled”’, he goes on to locate the real violence of these feelings in ‘Northumberland boozers’ in gangland where I suspect this violence also belongs to things kept ‘obscure’ to the people who feel them however situated in psychosocial settings – dark or obscure, for these are both translations of Lorca’s term ‘oscura’. There is no more feeling of being at the end of and also the vehicle of uncontrolled feelings than being strangled by your father. Of the two major later darker volumes of poems of Lorca, there is of the Diván del Tamarit (The Tamarit Divan). Tamarit houses many remnants of the extension of Moorish Islamic culture to Tamarit.

The second poem which takes a major part in what we are told about at the very end of the novel of the obscure beginning of Frank’s relationship with his cousin Lucía in Wylam, Northumberland (another favoured Tyneside town) at his grandmother’s house, where he first meets his uncle, Lucía’s father (she calls him Papi) in 1979. Papi sings in a way that Frank records as a ‘howl to an invisible moon. … The call is pained, or so it seems to him. Raw, an appeal of some kind, to the core of suffering’. These songs, which Frank wonders might betoken ‘something up with’ Papi are explained by Lucía as not so but songs from ancient Catalonian tradition: ‘Duende’.[4] Lucía watching Frank believes the latter has ‘been bit’ by it. [5] We are already in the midst of what Lorca called ‘dark’ and ‘obscure’ in the rare mixtures of elements (Moorish, Jewish, Catalan, Spanish) in Catalonian culture and his own psyche, for ‘duende’ (a song of uncontrolled emotion’ like rebetika in Greek culture) was alert to strange admixtures of pain, violence, death and sweetness in issues of love and its sequelae, including sometimes blood revenge (as in Lorca’s plays).

The poem mentioned at this point, and translated by Lucía is The Ghazal of Unexpected Love, with she names after translating it. The poem named in Spanish Gacela Primera: Del amor imprevisto (translated by Jane Duran and Gloria García Lorca as First Ghazal: Of unforeseen love) is typical of the late poems in which, according to Christopher Maurer, Lorca was attracted because of the association of the tradition of Persian ghazals to love that could be as directed to persons of the same sex as well as of the supposed binary opposite. Homoeroticism was easy to find in both Omar Khayyam and Hafiz.[6] But it was only easy to find if you had the key and to others was part of the darkness and obscurity of the poetry – difficult both to decipher or, with normative standards, understand. In such poems ‘duende’, which is Lorca’s mode of poetic and dramatic being finds its place with violence, death, and pleasurable agony in a garden or vineyard. See this stanza from the last named ghazal:

Siempre, siempre: jardín de mi agonia, Tu cuerpo fugitive para siempre, La sangre de tus venas en mì boca, Tu boca ya sin luz para mi Muerte.

Lucía translates this thus in what she calls to Frank ‘this brutish language of yours’:

Always, Always. Siempre. Siempre. Siempre. I love that … she brings her face close to his and whispers – “the garden of my agony, your body, forever fugitive. The blood of your veins in my mouth. Your mouth, dark for my death. [7]

For measure take Jane Duran and Gloria García Lorca’s translation, since it does not translate ‘sin lux’ as ‘dark but as ‘no light’ which is very, very different :

Always, Always: garden of my agony, Your body forever fugitive, The blood of your veins in my mouth, You mouth with no light for my death.

Frank becomes bitten by duende in a way that helps explain the obscurities of his behaviour in complex knots of familial and cross-border love matches (even those with a brother to whom death is a blessing) . Yet the purpose of this blog is really to relate this book to the poem (unnamed in the book) that gives it it’s title: ‘The Dead Don’t Bleed’. Only the Lorca link makes that title as complex as it actually is, for the title is easily one any popular thriller might take. But it actually comes from The Tamarit Divan too, a ghazal named Gacela VIII: De la Muerte Oscura (Ghazal VIII: Of the Dark Death).

This poem of obscure emotions of duende emerges midway through the novel. Frank Bridge has travelled to Spain, to Sierra de Cádiz in 2003 (the present time of the novel and from which other times in the past are recalled in chapters which flashback in time) after the death of Laurence Bridge, his Tyneside gangster father seen before in this blog, to inform his elder brother Gordon (he calls him ‘Gogs’) of that death. Neither brother have seen each other since Gogs fled to Spain with his father’s money from a particularly murderous robbery (we are to learn at the novel’s end) and the girl, Carol, who seemed, when in Dockland Wallsend, in East Newcastle, to be shared between Gordon and Frank. During that time Frank too has fled his father, completed a degree and began to write, living with his Spanish cousin and lover-wife, Lucía (associated with ‘light’ paradoxically in this no light novel), in Cacéres (but not then with any knowledge of his brother’s whereabouts). {Lucía by the way, as we shall learn later has been killed by an over-hasty hitman sent to bring Frank back to The North-East of England).

As Frank informs his brother and Carol about the changes in his life, especially his adventures in education and plan to write a book on Lorca, Carol insists on hearing Frank read out a Lorca poem. Gogs has no time for poems but in the end, on Carol’s ‘behalf’ and in his nastiest of styles of interaction says: “For fuck’s sake, just read one.. Put the cunt out of her misery”. Frank thinks he will but with little more grace than his brother: ’Fuck them both, he thinks, get it over and done with’. He speaks then ‘the words his beautiful wife taught him, a long time ago’.

“No quiero que me repitan que los Muertos no pierden la sangre ,” he sats, then pauses. What comes next, he wonders. His mind goes blank.

“Hang on”.

They stand in silence, gawping.

“Que la boca podrida sigue pidiendo agua,” he says, at last, raising his glass of water.

Gordon is aghast.

“You speak the lingo?”

“it’s not that hard, Gogs. Anyone could learn it.”

“What’s it mean?” she asks.

“Who fucking cares?” sys Gordon.

“Let’s drop it, Caz.”

“No. Tell me.”

Frank takes a tea towel off the countertop and wipes his forehead.

“Something like: don’t keep telling me the dead don’t bleed, that the rottng mouth still begs for water.”

“That’s deep,” says Carol.

“Deep as my arsehole.”

“Fuck off, Gordon,” says Carol.

I find the writing here dramatically fine and full of nuance, even the timing of the reading and its pauses, and the surface rationale of those pauses, for these learns are crucial and directly in the duende tradition ( I will add the text and translation from an attributed website below). This interaction of readings and interpretive translation of the Lorca poems is fully worked into this novel. It makes it a wonderful thing indeed. It interprets the family situation so fixed in Northumberland and Scotland in the European context of the conflictual in complex interactions within groups where bonding is essential but often ambivalent.

In the end I loved it. As for forgiving the bit about Kelso, I’m not sure – except that, I suppose psycho-geography can sometimes reach into realms of psychotic -geography.

Anyway – read the novel and please read Lorca.

With love

Steven xxxxxxxx

Addenda (the texts from source: https://americanghazal.com/2018/04/14/ghazal-of-dark-death-federico-garcia-lorca/ I Have placed in red the parts quoted in the novel.

“Gacela de la Muerte Oscura,” Spanish Original of “Ghazal of Dark Death”

Quiero dormir el sueño de las manzanas,

alejarme del tumulto de los cementerios.

Quiero dormir el sueño de aquel niño

que quería cortarse el corazón en alta mar.

No quiero que me repitan que los muertos no pierden las sangre;

que la boca podrida sigue pidiendo agua.

No quiero enterarme de los martirios que de la hierba,

ni de la luna con boca de serpiente

que trabaja antes del amanecer.

Quiero dormir un rato,un rato,

un minuto, un siglo;

pero que todos sepan que no he muerto;

que hay un establo de oro en mis labios;

que soy el pequeño amigo del viento Oeste;

que soy la sombra inmensa de mis lágrimas.

Cúbreme por la aurora con un velo,

porque me arrojará puñados de hormigas,

y moja con agua dura mis zapatos

para que resbale la pinza de su alacrán.

Porque quiero dormir el sueño de las manzanas

para aprender un llanto que me limpie de tierra;

porque quiero vivir con aquel niño oscuro

que quería cortarse el corazón en alta mar.

by Federico García Lorca,

From Diván del Tamarit (1934)

“Ghazal of Dark Death,” an English Translation by E.A. Melino

I want to sleep the dream of apples,

to escape the riot of cemeteries.

I want to sleep the dream of that child

who wished to cut out his own heart on the high sea.

I don’t want to hear that the dead don’t spill their blood;

that the rotting mouth is still begging for water.

I don’t want to hear about the agonies of the grass

or of the snake-mouthed moon

at work before sunrise.

I want to sleep a little,

a little, a minute, a century;

but all should know that I am not dead;

that there is a golden stable on my lips;

that I am the little friend of the West Wind;

that I am the looming shadow of my tears.

Cover me in the Dawn with a shroud,

because she will hurl clumps of ants at me,

and soak my shoes with hard water

so that I might slip her scorpion sting.

Because I want to sleep the dream of apples

to learn weeping that will cleanse me of the land;

because I want to live with that dark child

who wished to cut out his own heart on the high sea.

by Federico García Lorca,

From Diván del Tamarit (1934)

[1] Jonathan Lee (2026) ‘The Dead Don’t Bleed by Neil Rollinson review – a gripping tale of family and forbidden love’ in The Guardian (Wed 31 Dec 2025 07.00 GMT) available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/dec/31/the-dead-dont-bleed-by-neil-rollinson-review-a-gripping-tale-of-family-and-forbidden-love

[2] Neil Rollinson (2026: 29) The Dead Don’t Bleed London, Jonathan Cape

[3] Jonathan Lee, op.cit.

[4] Ibid: 159f.

[5] Neil Rollinson op. cit: 157 – 160

[6] Christopher Maurer (2017: 29f.) ‘Violet Shadow’ in Frederico García Lorca (ed. Jane Duran and Gloria García Lorca) Sonnets of Dark Love / The Tamarit Divan (parallel Spanish / English texts), London, Enitharmon Press.

[7] Neil Rollinson op. cit: 163f.