‘…, I no longer blamed myself for the sexual assaults I’d survived. I saw it like this: I could let myself sink in self-blame and self-pity or I could float and swim in this open water full of ambiguity’. (p. 241) ‘Love is abundant, an unlimited resource’ (p. 256). The aesthetics of the unlimited in Dean Atta, based on his 2024 memoir Person Unlimited: An Ode to My Black Queer Body, Edinburgh, Canongate.

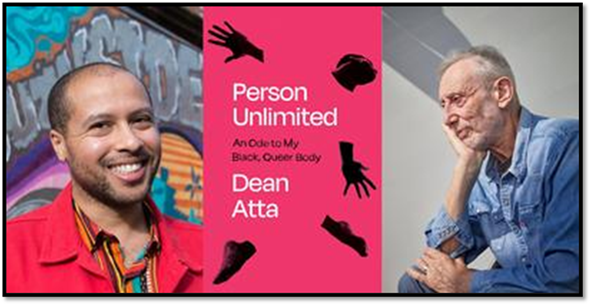

Dean Atta being interviewed about his memoir by the awesome Michael Rosen, a teacher at Goldsmith’s College, attended by Atta.

At the end of a recent short blog (see it at this link), written whilst I was still reading Dean Atta’s 2024 memoir I quoted lines from the final two stanzas of his poem I Come From …., and then added to my main point, a reference to one of the images in that poem about ‘people torn apart’:

I come from stories, myths, legends and folk tales.

...

I come from my own pen but I see people torn apart like paper,

each a story or poem that never made it into a book.… . And speaking of which, this is the most low-key reference to Orpheus and the sparagmos (a legend from that part Atta’s family that is Greek Cypriot) but here not about the poet who has been privileged to speak of himself but the marginalised unvoiced who have not.

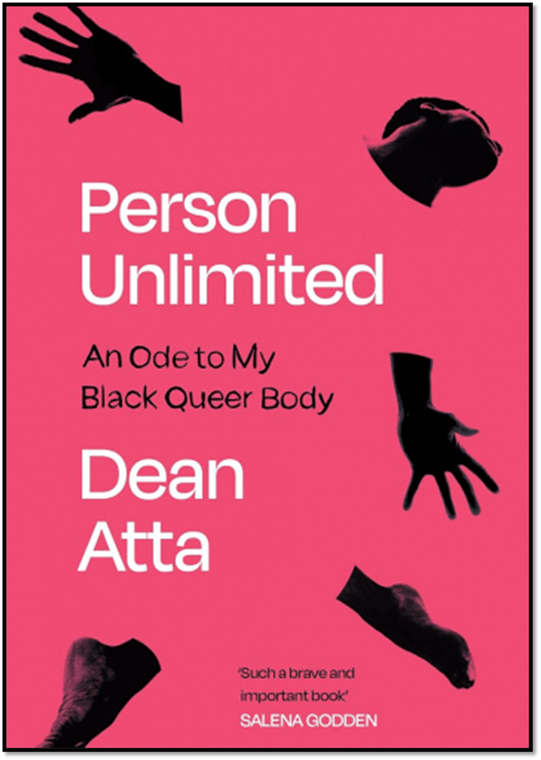

I have absolutely no evidence that Atta intended a reference to the myth of the tearing apart of persons known as sparagmos in Classical Greek, and associated with the mythical poet, Orpheus (and of course Prince Pentheus in Euripides’ play The Bacchae), except that it is one of the ‘stories, myths, legends and folk tales’ that contributed to what Dean Atta became – from his Greek Cypriot family. However, even if it is my obsession alone (you can see it is an obsession if you follow this link to one of my earlier blogs using the myth to explicate great texts from wonderful modern artists). But take a look again at the cover of Person Unlimited (reproduced in larger format below). The design is attributed and copyrighted to gray318and the design itself of fragments, two of which are iconic hand cut-out shapes (both of left hands as far as I can tell) and three are photographs, a face seen upwards from under the chin, an empty shoe and a sock (cover photographs attributed and copyrighted to istock. Neither source seems necessarily related to Atta directly and Dean’s influence on design or photograph choice is unknow. Yet look at it:

Am I wrong to feel an echo of Ovid’s description (in Book XI of Metamorphoses, line 29 onwards) of the tearing apart of the body of the poet, and his head consigned to the river Hebrus by the ‘troop of frantic women’ that are the Bacchae, where that severed head still sung of potentials for the earth unlimited to the violent partiality of the heteronormative gang who pursued him.

And some threw clods, and others branches torn from trees; and others threw flint stones at him, and, that no lack of weapons might restrain their savage fury then, not far from there by chance they found some oxen which turned up the soil with ploughshares, and in fields nearby were strong-armed peasants, who with eager sweat worked for the harvest as they dug hard fields; and all those peasants, when they saw the troop of frantic women, ran away and left their implements of labor (sic.) strown upon deserted fields—harrows and heavy rakes and their long spades after the savage mob had seized upon those implements, and torn to pieces oxen armed with threatening horns, they hastened to destroy the harmless bard, devoted Orpheus; and with impious hate, murdered him, while his out-stretched hands implored their mercy—the first and only time his voice had no persuasion. O great Jupiter! Through those same lips which had controlled the rocks and which had overcome ferocious beasts, his life breathed forth, departed in the air.

… His torn limbs were scattered in strange places.

The cover shows, however notionally, a body in parts, somewhat queerly configured, that might seem to emerge the pink medium that surrounds and separates the parts. I felt I see the body parts either appearing from a medium of pink as if a body connecting them were submerged in that medium, a pink sea, or, already fragmented from the whole body, floating in different directions away from the vacant pink centre of the medium. Do the ‘out-stretched hands’ (both left hands in fact) implore the mercy of the murderous Bacchae, furious that Orpheus had given up the love of women after the loss of Eurydice. Perhaps, or perhaps not! So much is up here for both association to and interpretation, by the viewer of the design and the associations and interpretations I invoke are far from receiving support in the text, though Atta often submerges his body in water.

I am inclined to believe that my longing for the presence of Orpheus is mine alone and that Atta goes further than embodying his fragmented intersectional being in classical legend, because on that cover design the title ‘person unlimited ‘relates and focuses the design’s meanings, as does reference to that poetic form we call an ode, relating to a ‘Black Queer Body’, for the body fragments are in tones of black and shades coloured by the background in which they float. The structural design of the book itself is a series of memories organised around fragments of the body, from top to toe (or ‘crown’ to ‘root’), diving into ‘roots’ to justify the preceding mix of organic metaphor. It is as if life in the unlimited person could choose any form of organic connection to unite the severed parts and functions of one’s life.

These parts and functions are listed in this memoir as body functions around which the partial and transmorphic expressions of Atta’s constantly shape-shifting ‘person’ coheres momentarily: crown, including the crown of hair that eventually becomes to signify the entirety of body hair, extending to and into the ‘hairy crack’ of Atta’s anus; sight, including the object and subject of the perceived beauty of bodies; voice, including how the voice becomes translocated between partial identities; left hand, which seeks attachment AND WRITES; belly, which seeks to absorb and evaluate the good of life, and, finally; roots, which ought to be located in one place but in ‘networks’ crosses surface boundaries and still hold commonality deep underground. Roots are not those things that connect only to the past but can be transplanted with and by care and love between domains that fight to stay isolated only as a folly. When saying this, Atta’s language becomes quite like to Shelley’s and other of the more adventurous Romantic poets:

Love need not be limited by language or location. Love is a galaxy of uncharted planets and stars. Love is abundant, an unlimited resource.[1]

Atta brings together the various identities of his life, even those that caused him shame because they were condemned by others like the ‘boy who wanted to wear dresses, a crown of daisies and play with Barbies’, and loves these as well as other people (indeed those actions are correspondent). Here is, in the form of Psyche, flying to, and becoming part of, the light:

My inner child, my mixed-race butterfly, fluttered in the golden light. Not a godforsaken fallen angel but a butterfly aching to beat his wings, to follow his instincts, to do what makes him happy.[2]

In my view, Atta explores here not some niche arena thrown up by deconstructive post-modernism but something intrinsic to the poetic vocation that need not start with Romantic poets but could extend back to definitions of poetry as an instinct to ‘becoming’ and recreation’ even in the very earliest times in which poems existed. But let’s not go there. Robert Browning struggled even to get a hard-headed humanist like John Ruskin to understand that poetry is ‘other’. Ruskin wrote to congratulate him on the volume Men and Women on December 2nd 1855, but adding that some poems were ‘the most amazing Conundrums that ever were proposed to me’.[3] ‘Limit your language!’, is the injunction Browning seemed to hear in this. He wrote back on the 4th December 1855:

I cannot begin writing poetry till my imaginary reader has conceded licences to me which you demur at altogether. I know that I don’t make out my conception by my language; all poetry being a putting the infinite within the finite. You would have me paint it all plain out, which can’t be; but by various artifices I try to make shift with touches and bits of outlines which succeed if they bear the conception from me to you. You ought, I think, to keep pace with the thought tripping from ledge to ledge of my ‘glaciers’, as you call them; not stand poking your alpen-stock into the holes, and demonstrating that no foot could have stood there; — suppose it sprang over there? In prose you may criticise so — because that is the absolute representation of portions of truth, what chronicling is to history — but in asking for more ultimates you must accept less mediates, nor expect that a Druid stone-circle will be traced for you with as few breaks to the eye as the North Crescent and South Crescent that go together so cleverly in many a suburb (my emphasis– SDB).

Browning rather wickedly points out that his purpose was not the kind of fashionable taste of conventional style That Ruskin too condemned – that he compares to the architectural structure of Georgian dual housing crescent formation, but as something more suggestive because poetry is ‘a putting of the infinite into the finite, the placing of a thing of limited proportions into vessels that are by nature necessarily ‘limited’ like language. Wasn’t this the explanation of the Gothic in Ruskin? I use Browning rather than Shelley here, because his critical language on poetry is so bluff. However, it should recall the cover of Person Unlimited, its structure and some of its moments of assertion that the ‘unlimited’ can only speak through means that are in themselves limited, because that is all we have, although most of us could try harder to see how limited our insularity of language, sex/gender, race/culture are, especially that insularity hedged around by power of dominance and presumed entitlement that is white, male and heteronormative.

For Atta each section of his life (sometimes equated with a certain time period in his life, but often extending either side of that period) like the care of his canerow distributed hair or plaits as an assertion of his Jamaican and / or ‘Black’ identity through his rather insular father, which cannot be even ‘touched’ by others, must give way to other avatars of self. Variations of hair type, from dreadlocks to Afro accompanied different discourses of race identity adopted by London communities in Atta’s youth. This coincided with some variants of nomenclature that partook of racism: an Asian member of a ‘Black’ [which was a political identifying term which meant then in some groups merely ‘non-white’] calls him by the N- word and is corrected, white gay men attribute Atta’s admired cock size to his Jamaican biological heritage and are dropped from consideration as sexual partners.

A fine piece of the writing comes when Atta tries to reconcile himself to the homophobia of some Jamaican-related men directed against ‘batty boys’, or fewer but still significant Afro identifying men, which as a youth he exaggerates he later finds. The invention of Flamingo Boy as part of his cabaret drag acting is a response to this. That part of the book is magical. It ends with Atta giving up the crown of his untouchable hair and becoming close cut, his crown one of flesh, if disguised by a crowning wig of pink hair.

But drag identity is not taken on in order that it endure, except as part of the an unlimited repertoire of parts and body performances and functions.

Left hands can be a sign of biological identity and inheritance but they also grasp those we need or want or desire, these functions themselves often metamorphosing. A voice can earn you a living in a role but it can also be manipulated [forced to speak in alien togues or denied] in exercises of internal power, just as it might take up ones own cause. Eyes are gates to, and signs of, beauty, but can too be distorted by power.

But the left hand is also Atta’s wring hand. He inherited from his Cyrpriot grandfather who spoke of being forced in school to change writing hands in order to conform. Atta uses all of this, recurrent, to remind one of the debates about what makes writing infinite and what limits it to finite ends. Does it limit him to write about gay or trans themes, as hid dad says of his first play, Rice and Peas. Are ‘well-meaning older writers’ correct to advise him not to ‘limit myself and my potential audience by focusing on gay characters and issues in my writing’? The same is said to him of confining his writing to Black characters and themes, or of not writing about white characters at all when selection is politically required. [4]

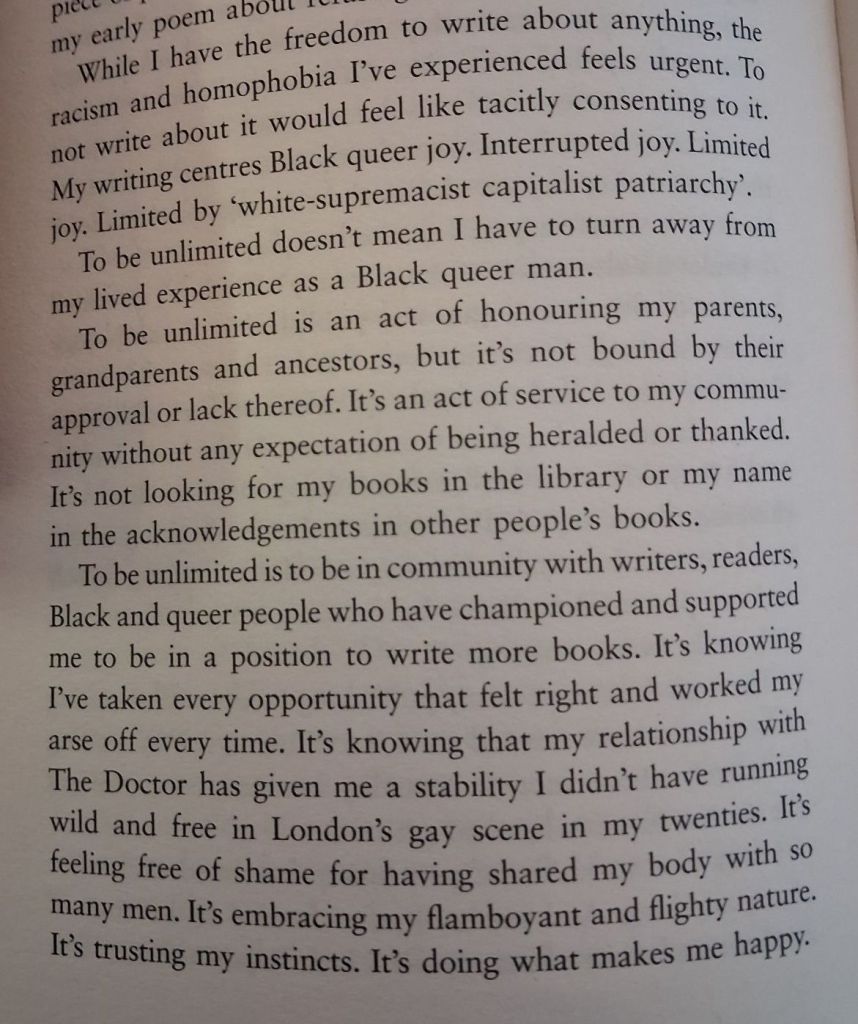

This how writing the ‘unlimited’ is written about in the text in a piece of reasoned prose that follows considerations mentioned above:

The context of this passage is important. Some self- definitions feel thoroughly determined, such as being left- handed, though these determinations can be challenged by self or hierarchical self-appointed authorities. That means that being unlimited means looking at the limits and determining which are ones we accept and which we do not. That means refusing some definitions, even self created identity definitions, should be as free a process as that of adopting such definitions in the time and space that feels right. It also means that imposing one’s own identity may not be a matter just of choice. The Greek Cypriot part of his family made Atta’s choices sometimes complex. Here, he speaks in an interview with Dhaliwal, in the online journal Feminist Dissent, which poses his identity in a fantasy of appearance and flight and exception,the idea of the Black Flamingo, which he first saw in reality in Cyprus, where it’s exceptional appearance reminded him of being labelled ‘Bob Marley’ by Cypriot peers:

I also think of the black flamingo as a metaphor for being black and queer – it represents an intersectional identity. My grandfather died last year and there were many things unspoken between us. I never came out to him. I felt he struggled to understand my blackness and I was not sure if he would be able to accept my queerness. [5]

Intersectional identity is about being unlimited because you accept limits, ones you choose, between identities which, in our real world are made to conflict but do not do so in imagination or in hope. After all being intersectional involves inequalities of power between each section of the person. Learning to think beyond fragments is learning to share love between oppressor and oppressed in order to mitigate the very fact of oppression, as a physical reality, feeling or thought.

Do read this beautiful book. And choose be with people proud and able to see their intersectionality, using it for good not passing for powerful evil.

With love

Steven xxxxxxx

[1] Dean Atta (2024: 256) Person Unlimited: An Ode to My Black Queer Body, Edinburgh, Canongate

[2] Ibid: 257

[3] R. J. DeLaura, ‘Ruskin and the Brownings’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 54 (1971–2), p. 324.

[4] Dean Atta op.cit: 151f.

[5] Atta, D. and Dhaliwal, S. (2019) An Interview with Dean Atta, Feminist Dissent, 4, pp. 279-282. Retrieved from:

https://doi.org/10.31273/fd.n4.2019.414