According to Socrates, at least as adherents of his definition of learning argue, learning is only tangentially about the acquisition of objects of learning – call them what you will, but here ‘skills and lessons‘ – that are the emergent by-products of a process that is never completed. Hence we ‘kindle the flame of learning’, and perhaps rekindle it during dark periods where it seems to flicker uncertainly in the damp air of ambient ignorance – that come so often these days, and keep it burning in the hope that its emergent goals will refine themselves to our changing needs. The illuminare website I refer to has a useful simple statement of the Socratic idea of ”learning’, once its leading light.

At the heart of Socratic philosophy is the belief that true wisdom comes from recognising one’s ignorance. Rather than presenting himself as an authority who imparts knowledge, Socrates guided his students to think deeply and question assumptions. This focus on active dialogue and inquiry remains a cornerstone of modern educational philosophy.

Socrates (469-399 BC) was a classical Greek philosopher who laid the foundation for Western philosophy. Unlike other teachers of his time, he did not write down his teachings. Instead, his ideas have been passed down through the works of his student, Plato, and later philosophers. The Socratic Method, his most enduring contribution, revolves around asking probing questions to stimulate critical thinking, rather than simply delivering information.

“The Kindling of a Flame”: Socrates’ Vision of Education : Socrates’ metaphor of education as “kindling a flame” reflects his belief that the role of a teacher is not to pour knowledge into a passive student but to ignite their innate curiosity. By sparking a desire for learning, educators can inspire students to seek knowledge independently, to question, to explore, and to engage deeply with the world around them.

That all seems very idealistic of course – so much so that people who do not adhere to it at all pretend that they do or still work within it, relegating the notion of bad education spoken of within it, namely “to pour knowledge into a passive student” into some stereotype of that inferior method like Dickens’ Gradgrind, and his malicious institutionalised mentee, Mr M’Choakumchild in Hard Times, Chapter 2 wherein the latter:

went to work in this preparatory lesson, not unlike Morgiana in the Forty Thieves: looking into all the vessels ranged before him, one after another, to see what they contained. Say, good M’Choakumchild. When from thy boiling store, thou shalt fill each jar brim full by-and-by, dost thou think that thou wilt always kill outright the robber Fancy lurking within—or sometimes only maim him and distort him!

The pouring metaphor is supplemented by the fact that what is poured into the supposedly ’empty vessels’ of the child’s mind is a boiling substance, which not only fills the child’s mind with products from a prescribed ‘store’ but kills off what lay unseen in the vessels, which Dickens calls childhood ‘Fancy’. Whatever the relation of childhood fancy to imagination in adulthood, something Coleridge made much of, the point Dickens emphasised is that the child is far from an empty vessel but filled already with an aspirant curiosity about the world which flickers in their imagination ready to be kindled into flame. Fires therefore are important symbols in Hard Times.

Remember most importantly that ‘facts’ in the latter novel and ‘skills and lessons’ in ourquestion are much more provisional than they seem. They emerge to meet a practical need that is also a function of learning to supply, but they are not fixed entities whose use value will diminish when the need change – either in the person or the environment which prompts them as needs, Learning is the process that edits, revises and replaces them with better products, for a period at least, and that process must be continuous – a thing we nowadays boil down to the unattractive label ‘lifelong learning’.

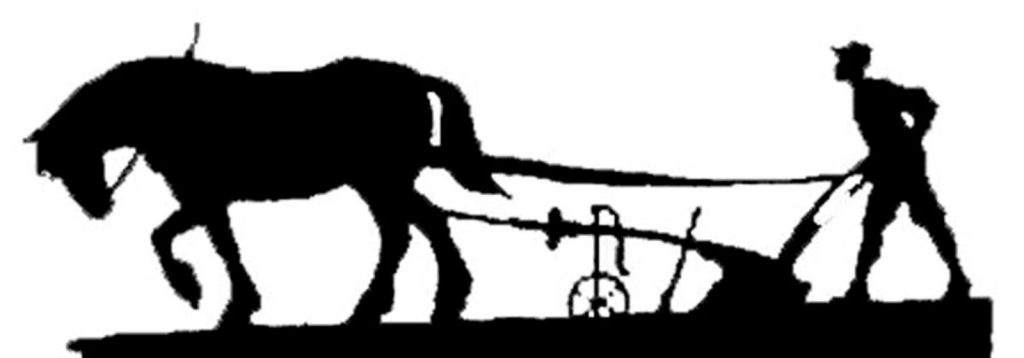

Even the etymology of the verb ‘to learn’ truly, and rustically, emphasises this – this being a word not of the academy but of the learning in early agriculture. Etymonline. com explores the word’s etymology thus:

learn (v.) : Middle English lernen, from Old English leornian “get knowledge, be cultivated; study, read, think about,” from Proto-Germanic *lisnojanan, with a base sense of “to follow or find the track,” which is reconstructed (Watkins) to be from PIE root *lois- “furrow, track.” It is related to German Gleis “track,” and to Old English læst “sole of the foot” (see last (n.1))./ It is attested from c. 1200 as “to hear of, ascertain.” Transitive use (He learned me (how) to read), now considered vulgar (except in reflexive expressions, I learn English), was acceptable from c. 1200 until early 19c. It is preserved in past-participle adjective learned “having knowledge gained by study.”

The Proto-Germanic root can mislead – we can think of a ‘furrow’ or a ‘track’ as something laid down in the past, and once refound followed slavishly. M’Choakumchild would relish that. But a medieval person at their plough would more often be making furrows to renew the ground from past uses, finding the ‘track’ in the meaning of inventing it, even if anew, if old models had demonstrable value.

Socratic method emphasises the learner. I remember a silly incident from when I taught at the Open university as an Associate. I preferred and used the term ‘learner’ religiously and never ‘student’, and applied it to myself. Other ‘tutors’, my peers, made such a public kerfuffle about this, as destroying the hierarchy of teacher and taught. For them the terms were honoured by a hierarchical notion of education not unlike M’Choakumchild though they peppered wit with unapplied knowledge of Vygotsky and Piaget (I taught psychology) – the teacher gave, the student received and then applied themselves to learning. Socrates emphasised his own ignorance before he addressed that of learners involved in the same process as he. He invented a method, that itself needs revision, that made learning a process that cannot be completed, though a person’s learning may end – for we all die after all.

The implications of this prompt question is that learning continues but on the model of an enormous Amazon warehouse and its logistics, shipping in and out various identical products that meet the current need (or demand – which isn’t always about need strictly speaking). I do not know whether learning is lost. It is in the governance of the USA and this is why Trump has been able to replace skills and lessons with lies serving a purpose to the ruling classes. It is becoming so in global governance. Education ministers no longer need idealism – they serve ‘growth’, but economic growth in the model of consumer capitalism bot personal and developmental growth beyond the limits of the material economy.

Am I hopeful that the flame will keep burning, when old geezers like me die, or even when the truth is acknowledged that what one person who may be like me matters not a jot in this world. I don’t think so. this is not age talking for the latter days are upon us already unless drastic social-economic revolution occurs , hopefully peacefully – but the powers that be are now re-arming. Don’t be fooled that this is all for use in external wars.

Bye for now

Love Steven xxxxxxx