Is this Flesh edible? Is it my Meat? Should it Be?

Preparing or Being Meat: Flesh on show.

A lot of what I want to say in this blog will refer to a distinction between the word ‘flesh’ and the word ‘meat’ which some consider to be essential to the context of referral – ‘meat’ only applying to muscle and fat tissue of an animal that is intended for culinary preparation and consumption as food, as in this webpage. Of course this distinction is far from comprehensive across contexts. When we call someone a ‘meathead’, we do not mean their head looks tasty to eat but that it is deficient of anything but meat, flesh without the nerve equipment conducive with thought and/or feeling. Moreover, in the King James Version of the Old Testament, God, after the Fllod – before which he only authorise plant-based food – makes his intentions clear about what may be eaten and what may not to Noah and his burgeoning family, and in this and other English translations he uses the term ‘flesh’ to describe what in it can be considered appropriately edible for a believer:

Genesis 9:3-4 (King James Version) 3 Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you; even as the green herb have I given you all things. 4 But flesh with the life thereof, which is the blood thereof, shall ye not eat.

The UK International Version nevertheless clearly gives credence to the distinction we have spoken about. It’s version reads:

Genesis 9:3-4 (New International Version - UK)

3 Everything that lives and moves about will be food for you. Just as I gave you the green plants, I now give you everything.

4 ‘But you must not eat meat that has its lifeblood still in it.

So far, so good. The phrase ‘eat flesh’ is common across the Bible, including the different relation between flesh and blood in Christian doctrine from that in Judaism where the incarnate body of God (or Son of Man) becomes both food and drink in Holy Communion. The message of the need to separate flesh and blood remains sacrosanct in orthodox faith. From the Bible too however comes the common use of the word ‘flesh’ to indicated not only the edible parts of an animal and the analogous softer parts of the human body, but also the sense of the profane section of human being, and tied strongly to religious law relating to sexual continence. Marriage is, considered after all a union of flesh generated through the spiritual in both Jewish and Christian doctrine, but that relationship applies even without the spiritual sacrament of marriage – in St Paul’s Epistle to the Corinthians, for instance.

1 Corinthians 6:16: King James Bible

What? know ye not that he which is joined to an harlot is one body? for two, saith he, shall be one flesh.

1 Corinthians 6:16: English Standard Version

Or do you not know that he who is joined to a prostitute becomes one body with her? For, as it is written, “The two will become one flesh.”

Sex unites in the flesh. Here a modern translation does not consider ‘meat’ an acceptable translation, though the analogy of appetite is a common way of linking hunger for flesh in both domains. However, in modern and common street language ‘meat’ is often the presumption of that attitude of those in what moral frameworks call relationships of ‘lust’, engaging only transactions of the body.Related not only to the sexualisation of the human body, but also its commodification (the body being considered as a purchasable and sellable object) the common phrase ‘meat market’ is understood by one website thus (although note that actual buying and selling is not necessarily intended, only the analogy of evaluation considered in terms of monetary value:

Origins and Historical Context of the Idiom “meat market”

The phrase “meat market” is a common idiom used to describe a place or situation where people are evaluated based on their physical appearance. This can refer to anything from a social event to an actual marketplace, but the underlying idea is always the same: people are being judged like cuts of meat in a butcher shop.

The origins of this idiom are unclear, but it likely dates back centuries to when humans first began trading livestock for food. In those days, animals were often sold at markets where buyers would inspect them closely before making a purchase. Over time, this practice became associated with other forms of evaluation, such as judging potential partners based on their looks.

In modern times, the term “meat market” has taken on new meanings and uses. It can be used to describe any situation where people feel objectified or reduced to their physical attributes. For example, some bars or nightclubs may be referred to as meat markets because they attract patrons who are primarily interested in finding sexual partners.

Despite its negative connotations, the idiom “meat market” remains popular today because it succinctly captures an uncomfortable truth about human nature: we often judge others based on superficial qualities rather than taking the time to get to know them as individuals.

Not thoroughly heteronormative in its assumptions, this passage may neglect versions of the idiom in the queer world, such as the ‘meat rack’ (which idiom has now taken the status of a place name replacing it original names as The Pines & Cherry Grove Area) of Fire Island (for my blog on an excellent book on Fire Island use this link).

With all this in mind let’s turn to one of my favourite Shakespeare plays The Merchant of Venice, about which I have blogged before in terms of its racism (linked here) and of one production that challenged its anti-Semitic nature (linked here). According to Dennis Austin Britton, both flesh and blood serve to denominate race, if in a distinct way, in The Merchant of Venice by establishing:

a connection between racial and religious identity, between outside (body features) and inside (blood and faith), through examining Jessica’s relationship to her father Shylock; the play interrogates the extent to which father and daughter share the same flesh and blood.

I have not read the full essay (and the link I give goes only to the chapter’s abstract), so I wonder if its concern in making this connection regarding the racial and religious identity of Jessica is applied to the central development of flesh (and ‘meat’) and blood contrasts in the play, or considers the role of that relationship in Jewish religious law, or kashrut (from the Torah based on the sections quoted from the Old Testament of the Christian Bible above) regulating the division of clean and unclean flesh for consumption, and which forbid the consumption of blood in flesh, requiring some method of post-butchery blood removal such as salting / curing.

In fact though the play uses the term ‘flesh’ consistently (almost) applied apparently not to consumable (as in the sense of ‘edible’) applications, but certainly commodifiable, Meat is discussed in a niche incident of the play’s final act, where Launcelot Gobbo, a servant, has left the service of Shylock the Jew and escaped with the Jew’s daughter, Jessica, into the Christian community and been consumed within it, as servant and wife of Lorenzo. This niche element of a scene hardly seems relevant to the play but is it? It is the kind of scene often explained as for the ‘groundlings’ of the theatre, but its ‘wit’ is lost on us and even in own time was probably more relished by the classes who loved to prove their superiority over the working classes by their skill in word-play.

LORENZO How every fool can play upon the word! ... Go in, sirrah, bid them prepare for dinner. LANCELET (sic.) That is done, sir. They have all stomachs. LORENZO Goodly Lord, what a wit-snapper are you! Then bid them prepare dinner. LANCELET That is done too, sir, only “cover” is the word. LORENZO Will you cover, then, sir? LANCELET Not so, sir, neither! I know my duty. LORENZO Yet more quarreling with occasion! Wilt thou show the whole wealth of thy wit in an instant? I pray thee understand a plain man in his plain meaning: go to thy fellows, bid them cover the table, serve in the meat, and we will come in to dinner. LANCELET For the table, sir, it shall be served in; for the meat, sir, it shall be covered; for your coming in to dinner, sir, why, let it be as humors and conceits shall govern.Lancelet exits. LORENZO O dear discretion, how his words are suited! The fool hath planted in his memory An army of good words, .... The Merchant of Venice, Act 3, Scene 5, c.line 54ff.

Shakespeare always alerts us to his own skill in ‘word play’, harping on the fact the ‘every fool can play upon the word’. Lorenzo is referring to a conversation Jessica has reported Gobbo had with her (line 30ff.):

JESSICA Nay, you need not fear us, Lorenzo. Lancelet

and I are out. He tells me flatly there’s no mercy for

me in heaven because I am a Jew’s daughter; and

he says you are no good member of the commonwealth,

for in converting Jews to Christians you

raise the price of pork.

The prohibition of pork meat is the only overt reference in the play to Jewish religious law that is specifically dietary, but it comes just before the nonsense Gobbo creates around words relating to the serving of food and specifically meat (the bit I have quoted from line 54 has the only two instances of the word ‘meat’ in the play) . Yet in this exchange the main witty ambiguity concerns the many meanings at the time (and some now) of the verb ‘to cover’, as described below on etymonline.com, with some key contradictory meanings bolded by myself:

cover (v.): mid-12c., “protect or defend from harm,” from Old French covrir “to cover, protect, conceal, dissemble” (12c., Modern French couvrir), from Late Latin coperire, from Latin cooperire “to cover over, overwhelm, bury,” from assimilated form of com-, here perhaps an intensive prefix (see com-), + operire “to close, cover,” from PIE compound *op-wer-yo-, from *op- “over” (see epi-) + root *wer- (4) “to cover.” / Sense of “to hide or screen” is from c. 1300, that of “to put something over (something else)” is from early 14c. Sense of “spread (something) over the entire extent of a surface” is from late 14c. Military sense of “aim at” is from 1680s; newspaper sense first recorded 1893; use in U.S. football dates from 1907. Betting sense “place a coin of equal value on another” is by 1857. Of a horse or other large male animal, as a euphemism for “copulate with” it dates from 1530s.

Gobbo plays games with the word ‘cover’ allowing its saucy meaning of animal copulation, also available to the word ‘Serve’, another French aristocratic or cavalier inheritance for how a stallion treats a mare. It is almost certain I think that the Elizabethan actors playing Gobbo would have unearthed lots of sexualised puns from Gobbo’s speech, for his indignation is based on the denial of sexual interest as well another meaning of ‘covering, that of being a dissembler rather than a true man. And all of this from a man who has left Jewish service norms to Christian ones. And all this around an absub concentration on a table ‘covered’ with ‘meat’!

Would Shakespeare have expected his audience to remember the idea of commodifiable and servable ‘flesh’, if not meat, is already at the centre of this play. Why does Shylock ask that his debt be covered by flesh? Salarino asks him directly: ‘Why, I am sure if he forfeit, thou wilt not take his flesh! What’s that good for?‘ What indeed. Shylock immediately turns his response into an imagination that the gains from usury should be something that feeds, as incomes do indirectly. But human flesh! It’s isn’t edible by humans or exchangeable for something that is, is it? Hence Shylock’s answer:

SHYLOCK To bait fish withal; if it will feed nothing else,

it will feed my revenge. He hath disgraced me and

hindered me half a million, laughed at my losses,

mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted

my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies—

and what’s his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not

a Jew eyes? Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions,

senses, affections, passions? Fed with the

same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to

the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer

as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not

bleed?

The Merchant of Venice, Act 3, Scene 2, c.line 52ff.

To ‘feed my revenge’ becomes away of feeding the the wounds created by Christian hatred of Jews, and merely because of that. His famous speech on the sameness of Jew and Christian raises the very contradiction otherwise discussed in the play. Are we the same if we are fed ‘with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, … as a Christian is?’ And, of course, Shylock has already said in the previous scene that the difference in how Jew and Christians feed does set them apart, in his view:

SHYLOCK Yes, to smell pork! To eat of the habitation

which your prophet the Nazarite conjured the

devil into! I will buy with you, sell with you, talk

with you, walk with you, and so following; but I

will not eat with you, drink with you, nor pray with

you.

The Merchant of Venice, Act 3, Scene 1, c.line 33ff.

Again the only dietary law addressed is the prohibition of the meat of the pig for orthodox Jews, not the equally well known one of not eating meat that still contains blood. Did Shakespeare again have this in mind in the way he allows Portia to humiliate him in the trial scene, for her instructions to him insist on what he has forgotten: that meat butchery involves blood as well as flesh and meat (for fish bait or whatever):

Therefore prepare thee to cut off the flesh.

Shed thou no blood, nor cut thou less nor more

But just a pound of flesh. If thou tak’st more

Or less than a just pound, be it but so much

As makes it light or heavy in the substance

Or the division of the twentieth part

Of one poor scruple—nay, if the scale do turn

But in the estimation of a hair,

Thou diest, and all thy goods are confiscate.

The Merchant of Venice, Act 4, Scene 1, c.line 338ff.

What Portia is reminding Shylock of is that to cut the flesh, even of a man, potentially turns that flesh into meat, even if no human intends to eat it. The court reproduces the flesh markets of London, where meat is sold by the pound – the weight of its blood included. The weight must be the exact required by the degree of our payment for it- no ‘more or less than a just pound’, for trade must be fair, must be ‘just’. Are we verging here on a reminder of God’s prohibition to Jews of the ‘lifeblood’ of meat or flesh. Christians, after all, eat their Godhead’s flesh and blood transubstantiated from the bread and wine in the Mass. Portia (cross-dressed as lawyer Balthazar) even seems to point that lesson:

PORTIA (as Balthazar)

Tarry a little. There is something else.

This bond doth give thee here no jot of blood.

The words expressly are “a pound of flesh.”

Take then thy bond, take thou thy pound of flesh,

But in the cutting it, if thou dost shed

One drop of Christian blood, thy lands and goods

Are by the laws of Venice confiscate

Unto the state of Venice.

The Merchant of Venice, Act 4, Scene 1, c.line 318ff.

Not any blood in this meat or flesh then, but ‘Christian blood’. Had Shylock remember that the flesh was to ‘feed’ his ‘revenge’, would he have also remembered that it would come in unclean condition by Jewish dietary law, instinct with lifeblood. As I thought this through (fancifully or not) I wondered if this play were not even more anti-Semitic than it seems to some, who stress the speech about Christians being the same as Jews, ‘fed with the same food’. And if Shylock was conscious that if you are pricked, you ‘bleed’, would he have taken a knife to the flesh of the Christian with no reference to blood.

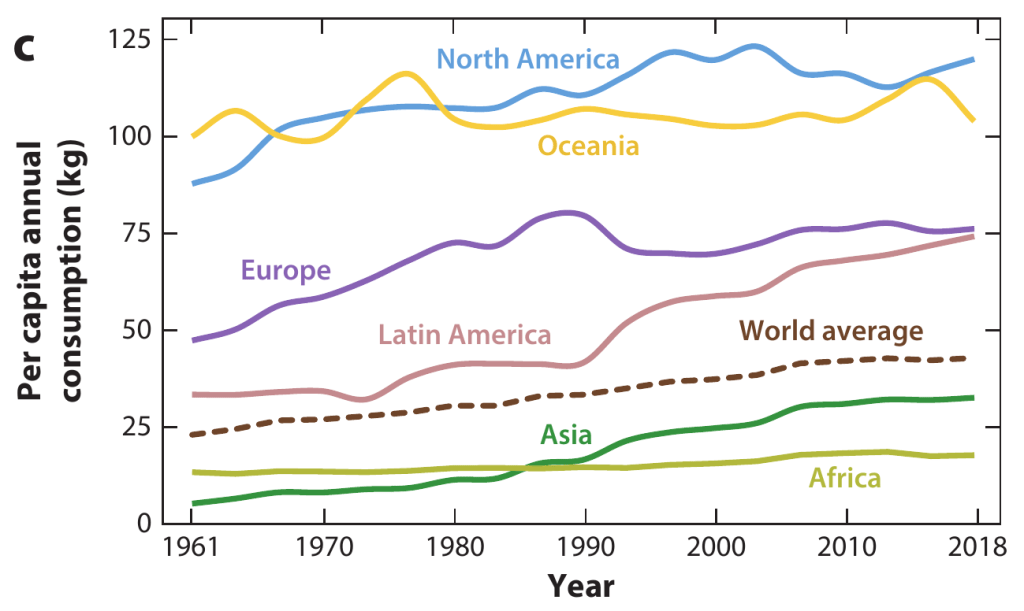

Sometimes, there are problems in plays we do not always know to be consciously put there. However, Shakespeare reminds me of what my answer to this prompt question is. If you treat life as your ‘meat’ (appetitively in nutrition or sex) then you will take life without reason and for no good, for no-one needs meat to live healthily and most rich Western countries eat such a surplus of it, they live very unhealthily and damage the ecosphere at the same time. And see the distribution of meat per capita consumption:

“Data from FAO Food Balance Sheets (https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FBS).”by the Authors of the study: Martin C. Parlasca and Matin Qaim – https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-resource-111820-032340

Meat is not only murder then, and perhaps suicide in slow version, but also a measure of global inter-human oppression, to say nothing of the oppression of warm-blooded animals (and perhaps the same of cold-blooded ones too says this guilty pescatarian.

Veal carcasses in the meat products sector of the Rungis International Market, France.By Photo: Myrabella / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26955402

Those veal carcasess were once sentient:

Bye for now

With love

Steven xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx